Evaluation of the Impacts of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements - Federal and Inuvialuit Perspectives

Final Report

Date: November 2013

Project No. 11035

PDF Version (1,417 Kb, 161 Pages)

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Section One: Federal Component

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Relevance

- 4. Performance - Legal, Economic, Social and Gender Impacts

- 5. Performance – Achievement of Immediate Outcomes

- 6. Performance: The Achievement of Intermediate Outcomes - The Inuvialuit Final Agreement

- 7. Key Challenges

- Section Two: Inuvialuit Component

- 8. Introduction

- 9. Methodology

- 10. Ownership, Access to, and Managing Land and Resources

- 11. Cultural Vitality

- 12. Institutions and Decision-Making Processes

- 13. Economic Opportunities

- 14. Social Development

- Section Three: Conclusions and Recommendations

- 15. Conclusions

- 16. Recommendations

- Appendix A – Comprehensive Land Claims Agreements and Claims Related Self Government Agreements

Executive Summary

Comprehensive land claim agreements and self-government agreements are based on two federal government policies: The Comprehensive Land Claims Policy (1986); and the Government of Canada's Approach to Implementation of the Inherent Right and the Negotiation of Aboriginal Self-Government (1995) - most commonly referred to as the Inherent Right Policy. Moreover, in accordance with the British Columbia Treaty Commission Act, 1995, negotiations in British Columbia follow a unique negotiation process where negotiations are overseen by an independent facilitator, the British Columbia Treaty Commission.

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook an Evaluation of the Impacts of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements. The purpose of the evaluation was to assess relevance and the extent to which expected outcomes of comprehensive land claim agreements and self-government agreements are being achieved. Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved by the Department's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in June of 2012.

AANDC engaged the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation to participate in the evaluation process. AANDC's vision is to conduct performance measurement and evaluation work with Aboriginal signatory groups with the expectation that this level of heightened engagement will allow parties to articulate their interests and target performance measures and evaluation work to meet their own specific needs and the needs of all parties.

The evaluation report contains three sections: the federal component; the Inuvialuit component; and conclusions and recommendations.

Federal Component

The scope of the federal component includes stand-alone comprehensive land claim agreements and claims-related self-government agreements. Stand-alone self-government agreements were not included in this evaluation. The evaluation, though covering all aspects of modern treaties, focuses on lands, resources and economic development. An evaluation of self-government, to take place in fiscal year 2014-15, will further assess the impacts related to governance, programs and services.

Evaluation results were based on the analysis of data obtained through document and literature review, key informant interviews, file review, financial and economic analysis, statistical analysis, contingent liability analysis and gender analysis.

The federal component supports the following findings regarding the relevance and performance of modern treaties.

Relevance

Canada has established eight stand-alone comprehensive land claim agreements and 16 comprehensive land claims with related self-government agreements, which cover over 40 percent of Canada's land mass. These agreements have established an ongoing relationship regarding Aboriginal rights and title in Canada. The implementation of modern treaties remains aligned with federal government priorities, roles and responsibilities.

Where modern treaties have been concluded, they aid Canada in better managing the reconciliation of s.35 rights based upon negotiated rather than court dictated outcomes. In this way, modern treaties have made an important contribution to minimizing court disputes concerning rights and title and have produced valuable and positive results for government, Aboriginal communities and the broader Canadian society. Evaluation findings suggest however, that the current s.35 policy framework is not fully responsive to the evolving legal framework.

There is a continuing need for clear, unambiguous agreements and close monitoring of the implementation of these agreements in order to mitigate legal and contingent liability risks as well as ensuring ongoing positive working relationships with treaty partners.

Performance

Modern treaties provide a number of mechanisms through which they support economic development. The formalization of property rights helps individuals derive full benefits from the ownership of resources, which allows for the maximization of gains from trade and supports other transactions in the economy. In addition, modern treaties provide for direct capital transfers to beneficiary organizations, which have the potential to support investment activity, as well as social and educational initiatives with possible long-term economic benefits. These benefits represent significant progress towards the modern treaties immediate expected outcomes. Specifically, the agreements provide structures for clear and formalized land ownership leading to well understood rights regarding management and access. In addition, the formalization of property rights also provides certainty of ownership and contributes to a more stable economic environment.

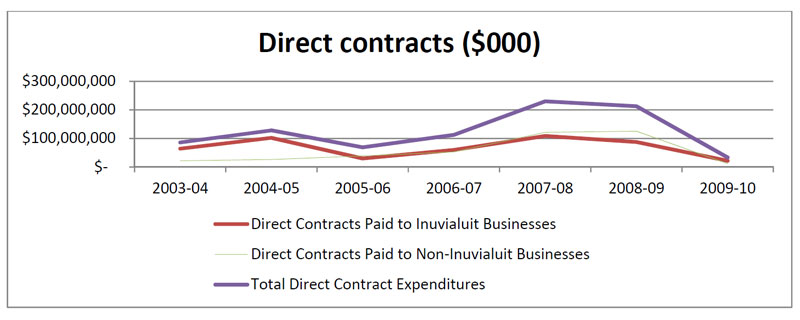

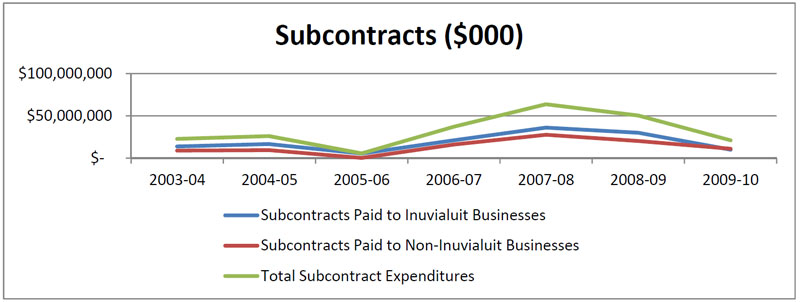

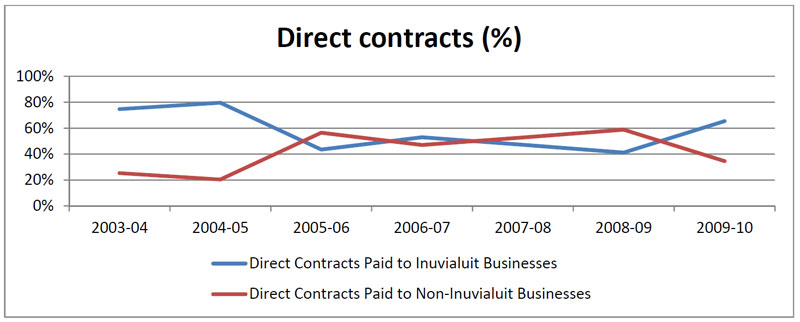

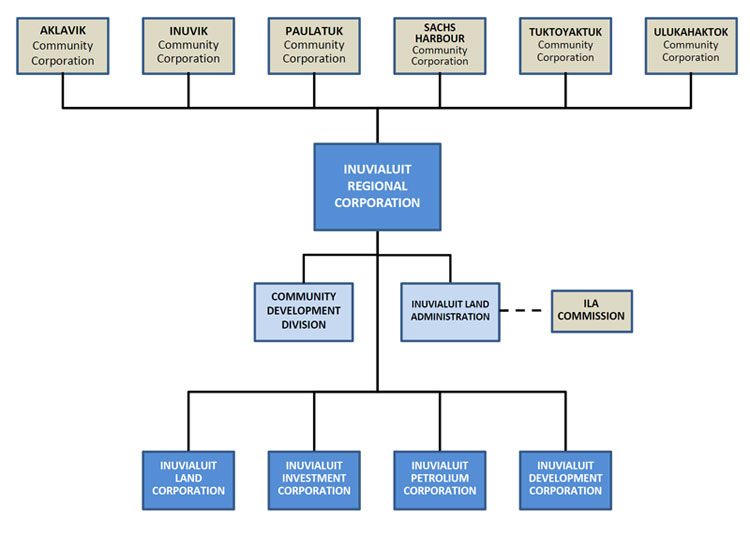

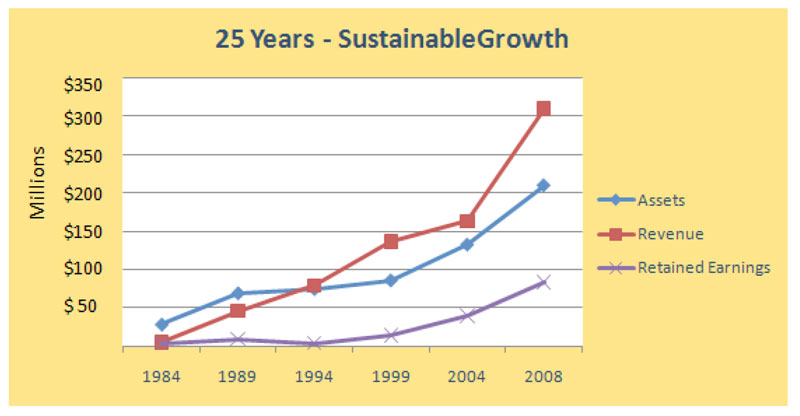

The Inuvialuit Final Agreement was examined in detail as part of the federal component to assess results from at the intermediate outcome level. The analysis demonstrated how provisions in the Agreement have provided additional development benefits. It is very unlikely that the corporate structures would have been formed in the absence of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement. These corporations, including the Inuvialuit Trust, have been active in the regional economy, providing both direct and indirect benefits to signatories of the Agreement. Not the least of these is direct dividend payments to beneficiary shareholders. Despite these gains, there does not seem to be strong evidence of a marked change in other aspects of social and economic development in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region.

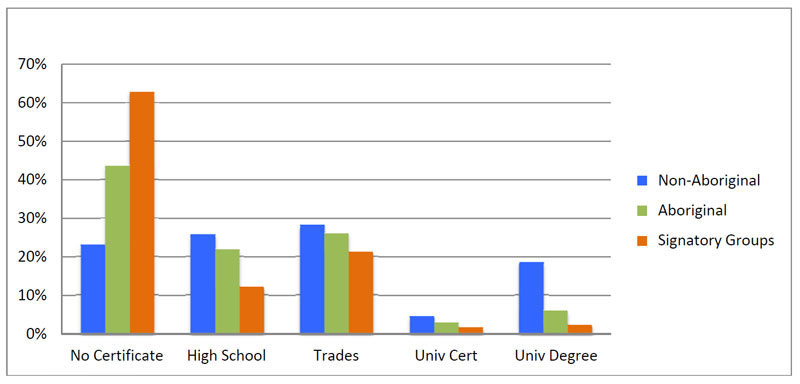

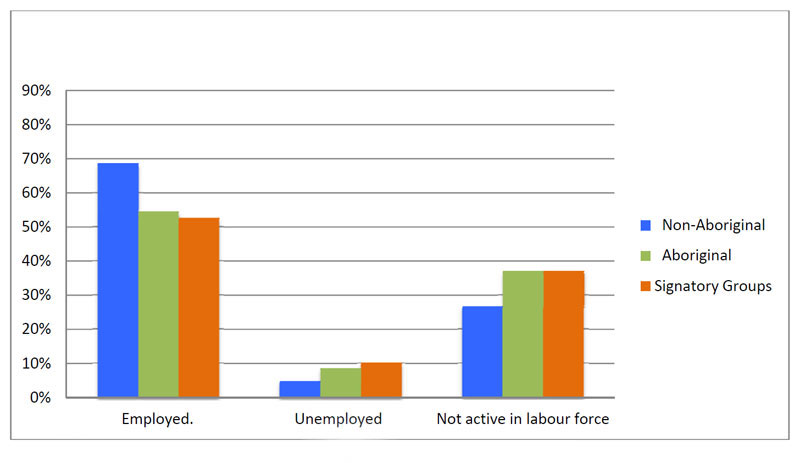

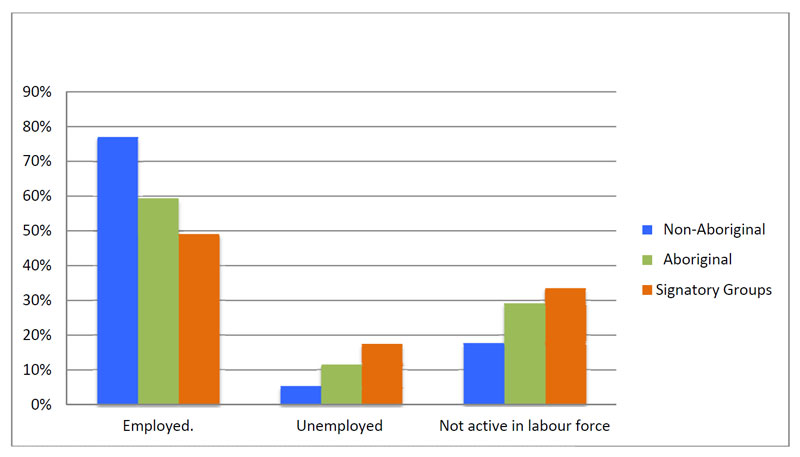

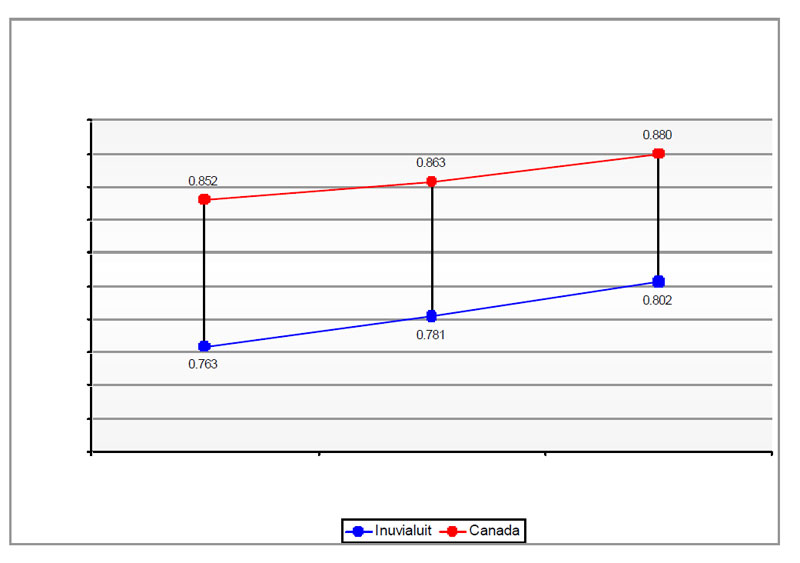

These findings were consistent with an analysis of social and economic indicators based on the 2006 Census data, which suggests that Aboriginal signatory groups lag behind both the non-Aboriginal population and the Aboriginal identity population in education, income, and labour force characterises, all which are important to full participation in the Canadian economy and society. However, there remains a critical lack of ongoing monitoring and analysis regarding the impacts of modern treaties to fully understand the progress being made.

Agreements and side agreements provide the structures to support the intermediate outcomes. Structures for governance, programs and services, land and resources management are strongly in place, with structures for economic development in place but not included in all agreements. Though these structures are in place, there remains the perception that modern treaty obligations have not been fully implemented resulting in barriers to progress. Additional analysis, specifically related to how well the federal government is implementing the provisions contained in modern treaties, needs to be undertaken.

Inuvialuit Component

The Inuvialuit Final Agreement is a stand-alone comprehensive land claim. The goals of the Agreement are to:

- Preserve Inuvialuit cultural identity and values within a changing northern society;

- Enable Inuvialuit to be equal and meaningful participants in the northern and national economy and society; and

- Protect and preserve the Arctic wildlife, environment and biological productivity.

The Inuvialuit component focuses on the socio-economic impact of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement by identifying the strengths and threats impacting progress towards achieving the goals of the Agreement.

The research for the Inuvialuit component was based on analysis of key informant interviews and an extensive literature review of Inuvialuit Regional Corporation's internal documents, reports, and publications.

The Inuvialuit component supports the following findings regarding the socio-economic impact of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement.

Ownership, Access to, and Managing Lands and Resources

One of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation's strengths is its institutional stability, which is well recognized by governments and industry. This underpins the stability of its participation in the co-management regime, along with its own land management. It is also a strong element in the positioning of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation as a credible and equal partner with governments and industry in relation to land management decision making. Obstacles in the way of progress toward effective land management and administration are outside of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation's control, and require the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation to put resources into strategizing, negotiating and mitigating these obstacles. In some respects, this is simply part of its organizational mandate, but it nonetheless requires expenditure of resources better spent elsewhere.

Cultural Vitality

Issues with respect to promoting cultural vitality and the aligned goals of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement are ones that relate to a combination of power relations, resources, and ongoing colonization impacts. If the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation's efforts toward promoting and developing cultural vitality are to succeed, to a large extent, individual Inuvialuit must take responsibility for living their culture to the greatest extent possible. Canada, for its part, must recognize that this personal responsibility is most fully realized when there are supports and resources to draw on from the larger community. Establishing those resources is an area where the treaty partners each have a role. In particular, Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories must view the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation as a service delivery partner whose capabilities are directly impacted by the funding and accountability approaches taken by funders.

Institutions and Decision Making

The Inuvialuit Regional Corporation is a well-established, stable, financially independent institution that meets all criteria for success and stability set out in academic research projects relating to Indigenous governance. This reality underpins its capacity and success with respect to its organizational scope. However, the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation’s progress toward achieving its land claim goals is continually hindered by external policy choices of partners. This is with respect to both its institutional functionality and with respect to the social and living conditions of the Inuvialuit population, which creates issues both with demand for services and with respect to its future institutional development.

Economic Opportunity

A different approach needs to be taken to increase economic wellness in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. Efforts to promote and provide economic opportunity are beyond land claim implementation on its own. Critical to a different approach is understanding that the characteristics of the "subsistence economy" in most small communities in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region should not be interpreted as failed capitalism. Subsistence economy characteristics - such as that reciprocity rather than profit is the animating logic of economic activity – need to be understood as features of the system rather than issues or problems to be solved or made to disappear. This understanding allows for economic approaches premised on features of the subsistence economy, rather than features of a non-existent market economy.

Social Development

The Inuvialuit Regional Corporation’s institutional stability positions it to credibly and ably provide social policy programs to its beneficiaries on behalf of and in partnership with other external organizations. Notably, it has begun significant work on identifying and gathering statistical data as a basis for institutional program focus and delivery. What undermines Inuvialuit progress toward the social goals of the land claim lies mostly outside of the control of Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. In particular, colonial policy-induced social suffering poses a significant near-term and long-term threat to the Inuvialuit Settlement Region’s social development, the institutional development and stability of the Corporation, and the potential for future generations to continue the impressive success achieved to date.

Conclusions

The evaluation found that comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements have put in places structures for governance, programs and services, land and resource management, and economic development. In the case of the Inuvialuit, the stable, credible, highly functional institutional structures that are in place at the corporate level, position the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation to work towards realizing the Inuvialuit Final Agreement goals. It is unlikely that the corporate structures would have been formed in the absence of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement.

However, social and economic indicators suggest that Aboriginal signatory groups lag behind both the non-Aboriginal population and the Aboriginal identity population in education, income, and labour force characteristics. The Inuvialuit component found that the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation's institutional stability and economic success are threatened mainly by the opportunity costs created by its resources being required to address social issues. Socio-economic conditions faced by a majority of its shareholders mean that many Inuvialuit are not being positioned to gain the skills and experience required to ensure the continued success of the Corporation and its socio-economic interests. Across many agreements there remains the perception that modern treaty obligations have not been fully implemented resulting in barriers to progress.

Recommendations – FederalFootnote 1

It is recommended that AANDC:

- Review the recommendations stemming from the Inuvialuit component, and provide comments on behalf of Canada to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on the Inuvialuit recommendations.

- Continuing with the Implementation Change Agenda, strengthen the "whole of government approach" to monitoring and implementing treaty obligations and risks.

- Undertake a research agenda to support the monitoring of the impacts of modern treaties.

- To improve results-based reporting, coordinate the ongoing monitoring of the effectiveness of the implementation of modern treaties.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Impacts of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements

Project #: 11035

1. Management Response

This evaluation is the first of three evaluations that will be used in 2015 to fulfill Canada's requirements for the renewal of financial authorities related to comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements.

A joint approach was undertaken with the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, which allowed for an in depth evaluation from both perspectives. However, performance measurement methodologies in the future must include all treaty partners for it to be an effective method of measuring the impacts of comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements. Analysis that exclude the role of one or more treaty partners lacks the full context required to create a clear path to improve on the impacts of these agreements.

The evaluation concluded that the implementation of modern treaties remains aligned with federal government priorities, roles and responsibilities. It also concluded that: "modern treaties have made an important contribution to minimizing court disputes concerning rights and title and have produced valuable and positive results for government, Aboriginal communities and the broader Canadian society. Evaluation findings suggest, however, that the current s. 35 policy framework is not fully responsive to the evolving legal framework". Finally the evaluation noted: "There however remains a critical lack of ongoing monitoring and analysis regarding the impacts of modern treaties to fully understand the progress being made".

The evaluation findings are consistent with the Implementation Branch's current work in implementing a "whole of government approach" to monitoring and implementing obligations and risks. In 2009, an Implementation Management Framework was approved by the Federal Steering Committee for a three year pilot. The Implementation Management Framework seeks to better coordinate the federal response to the implementation of Canada's legal obligations. Included is the development of guides and other resource material for federal implementers and accountability and monitoring tools such as CLCA.net and the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System. The Implementation Management Framework is currently being evaluated as to its efficacy and this work is scheduled to be completed in the fall of 2013.

Although the evaluation noted the extent to which comprehensive land claim and self-government agreements have impact on the ultimate outcome being: creating strong and self-reliant Aboriginal individuals, communities and governments, there were also a few limitations. In order to fully understand the impact these agreements have, it is important to have a joint evaluation with all treaty partners. While the Department reached out to several signatories for a commitment to undertake a joint evaluation, only one signatory was in a position to participate. This limits the extent to which we can assess the findings of the evaluation. The other limitation was the lack of available comparable data. With only the 2006 Census available to evaluators, it is difficult to rely too heavily on the conclusions made. These shortcomings to the evaluation methodology are addressed in our response to the evaluation recommendations.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Review the recommendations stemming from the Inuvialuit component, and provide comments on behalf of Canada to Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on the Inuvialuit recommendations. | We do concur. | Director, Implementation Branch, Treaties and Aboriginal Government | Start Date: Winter, 2013 |

| Review of the Inuvialuit recommendations has begun. Canada will provide comments to Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on those recommendations that are directed towards Canada. | |||

| 2. Continuing with the Implementation Change Agenda, strengthen the "whole of government approach" to monitoring and implementing treaty obligations and risks. | We do concur. | Director, Implementation Branch, Treaties and Aboriginal Government | Start Date: already begun |

| Work has already begun on the Implementation Change agenda and the development of resources, accountability and monitoring tools and training/assistance for other government departments. | |||

| 3. Undertake a research agenda to support the monitoring of the impacts of modern treaties. | We do concur | Director, Implementation Branch, Treaties and Aboriginal Government | Start Date: already begun |

| AANDC has approached academia with the view of supporting academic research on the impacts of >comprehensive land claims agreements and self-government agreements. Any initiative to monitor impacts requires the participation of both government and Aboriginal signatories. We will continue to reach out the Land Claims Agreement Coalition with the view of collaborating on this initiative. | |||

| 4. To improve results-based reporting, coordinate the ongoing monitoring of the effectiveness of the implementation of modern treaties. | We do concur | Director, Implementation Branch, Treaties and Aboriginal Government | Phase 1 – Amend Current PM Strategy |

| Implementation Branch monitors the implementation of obligations, and is currently participating in the Performance Measurement Strategy for the Impacts of comprehensive land claims agreements and self-government agreements to support AANDC's Performance Measurement Strategy Portfolio Action Plan, which support Program Alignment Architecture Program 1.3. |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on November 8, 2013, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on November 18, 2013, by:

Gina Wilson

Treaties and Aboriginal Government, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of the Impacts of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on November 22, 2013.

Section One: Federal Component

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook an Evaluation of the Impacts of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements. The purpose of the evaluation was to assess relevance and the extent to which expected outcomes of comprehensive land claim agreements and self-government agreements are being achieved.

1.2 Description of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements

Background

Comprehensive land claim agreements and self-government agreements (hereafter "modern treaties") are based on two federal government policies: The Comprehensive Land Claims Policy (1986); and the Government of Canada's Approach to Implementation of the Inherent Right and the Negotiation of Aboriginal Self-Government (1995) - most commonly referred to as the Inherent Right Policy.

The Comprehensive Land Claims Policy stipulates that land claims may be negotiated with Aboriginal groups in areas where claims to Aboriginal title have not been addressed by treaties or through other legal means. Comprehensive land claims are based on the assertion of continuing Aboriginal rights and title. Comprehensive land claim agreements provide certainty and finality respecting rights to ownership, use of lands and resources, including marine resources, which may contribute to increased economic development and self-sufficiency for Aboriginal groups. They provide a framework which encourages social and economic development, thereby benefiting Aboriginal people, government and third parties. Comprehensive land claim agreements also foster the development of institutions at both the community and collaborative signatory levels that facilitate the achievement of various planned outcomes arising from the agreements.

Under the Inherent Right Policy, the Government of Canada's recognition of the inherent right of self-government is based on the view that the Aboriginal peoples of Canada have a right to govern themselves in relation to matters that are internal to their communities, integral to their unique cultures, identities, traditions, languages and institutions, and with respect to their special relationship to their land and resources. Self-government agreements set out arrangements for Aboriginal groups to govern their internal affairs and assume greater responsibility and control over the decision making that affects their communities.

The other significant feature of self-government agreements is the change in relationship between the parties. A new relationship is created wherein Aboriginal signatories constitute governments in their own right. As a result, the parties to the agreements form government-to-government-to government relationships that transform how they relate to and collaborate with one another. Self-government agreements include a provision that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms will apply to Aboriginal governments and institutions in regard to all matters within their respective jurisdictions and authorities. They provide beneficiaries under the agreement with the continued protection of the Charter.

In accordance with the British Columbia Treaty Commission Act, 1995, negotiations in British Columbia follow a unique negotiation process where negotiations are overseen by an independent facilitator, the British Columbia Treaty Commission. These negotiations are founded upon the 19 recommendations that were made by Canada, British Columbia, and the First Nations Summit as outlined in The Report of the British Columbia Claims Task Force of 1991.

There are currently 24Footnote 2 completed modern treaties involving 94 communities, which cover over 40 percent of Canada's land mass.Footnote 3 See Appendix A for listing of agreements.

- Sixteen comprehensive land claims with related self-government agreements involving 30 communities, and

- Eight stand alone comprehensive land claim agreements involving 64 communities.

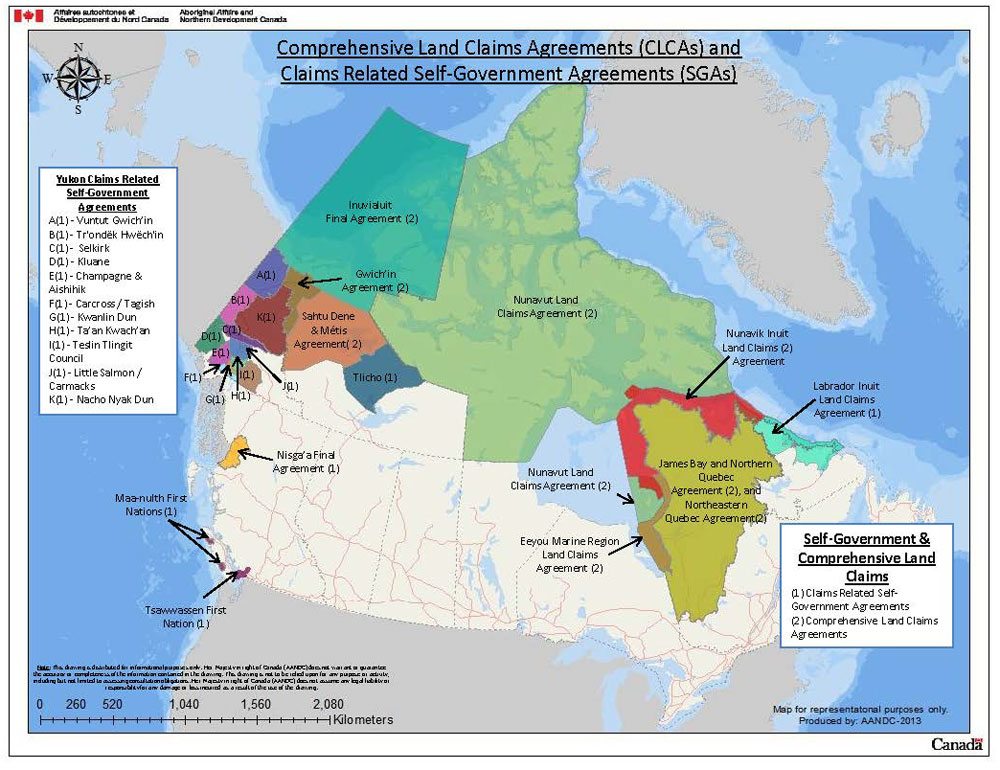

Description of Comprehensive Land Claims Agreements (CLCAs) and Claims Related Self-Government Agreements (SGAs)

This map of Canada shows the comprehensive land claims agreements and Claims related Self-Government agreements throughout Canada.

In British Columbia, the following First Nations which signed Self-Government Agreements are identified: Tsawassen Fist Nation, Maa-nuth First Nation and Nsga'a First Nation.

In the Yukon, the following First Nations which signed Self-Government Agreements are identified: Vuntut Gwich'in, T'rondek Hewch'in, Selkirck, Kluane First Nation, Carcross/Tagish, Kwanlin Dun, Ta'an kwach'an, Teslin Tlingit Council, Little/Salmon/Carmacks, and Nacho Nyak Dun Self-Government jurisidictions are identified on the map of Canada.

In the Northwest Territories, the following First Nations/Inuit settlement areas which have signed Self-Government agreements or final agreements are identified: Tlicho, Sahtu Dene and Metis, Gwich'in, and Inuvialuit.

In Nunavut, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement is highlighted showing that all of Nunavut is under the land claim.

In Quebec, the following Self-Government Comprehensive Land Claims are labeled: Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Agreement, James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and Northeastern Quebec Agreement, Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement.

In Labrador, the Labrador Inuit land claims agreement is outlined to show the area of its jurisdiction.

Management

All parties are responsible for working together to implement the provisions of their modern treaties, for setting priorities, evaluating progress and making adjustments as necessary. The Implementation Branch of the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector of AANDC oversees and coordinates the cross-departmental federal role in the implementation of modern treaties.

Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The primary stakeholders of modern treaties are the Aboriginal signatory groups, the federal government, and the relevant provincial/territorial government. All parties must work cooperatively towards the fulfillment of the obligations under the agreements in a transparent and accountable manner. The parties to an agreement have both party-specific and joint obligations to fulfill.

Although all Canadians, federal/provincial/territorial governments, and business/industry are expected to benefit from the settlement and implementation of modern treaties, the primary beneficiaries are expected to be the Aboriginal signatory groups.

Resources

Table 1 illustrates the 2012/13 AANDC expenditures on the implementation of modern treaties.

| Program Alignment Architecture (PAA): Sub Activities |

Actual Fiscal Year 2012/13 | |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation of Modern Treaty Obligations (Sub Activity 1.3.1 PAA) |

Grants & Contributions (Vote 10) | 312,053,018 |

| Operating (Vote 1) | 7,025,573 | |

| Total | 319,078,591 | |

| Management of Treaty Relationships (Sub Activity 1.3.2 PAA)Footnote 4 |

Grants & Contributions (Vote 10) | 298,314,586 |

| Operating (Vote 1) | 2,231,078 | |

| Total | 300,545,664 | |

| Total Implementation Costs for Modern Treaties | Grants & Contributions (Vote 10) | 610,367,604 |

| Operating (Vote 1) | 9,256,651 | |

| Total | 619,624,255 | |

Recent Evaluation and Audit Activities

The Impact Evaluation of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements was approved at the Audit and Evaluation Committee in February 2009. It found that the agreements have brought clarity and certainty to settlement lands, enabling Aboriginal groups to benefit from resource development and helping to create a positive environment for investment. The agreements have also had a positive impact on the role of Aboriginal people in their settlement area's economy and their relations with industry as well as ensuring that they have a meaningful and effective voice in land and resource management decision making. However, there has been a perception that the federal government has not sufficiently recognized the costs associated with the consultative approach and the land and resource management structures. There is also the perception among Aboriginal representatives interviewed for the evaluation that the federal government has been primarily interested in addressing the letter of the agreements and not the true spirit and intent, resulting in barriers to progress.

The Evaluation of the Federal Government's Implementation of Self-Government and Self-Government Agreements was approved at the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in February of 2011. It found that the Inherent Right Policy has provided a flexible framework from which self-government has been, and continues to be, negotiated and that positive impacts have been demonstrated within self-governing communities. However, a lack of shared vision exists between the federal government and Aboriginal communities regarding self-government and how it is to be operationalized within the framework of the Inherent Right Policy. National Aboriginal Organizations have been highly critical of the Inherent Right Policy and Aboriginal governments have expressed difficulty in establishing a government-to-government relationship with the Crown. This may be contributing to misunderstandings and miscommunications regarding the interpretation of the policy and contributing to the high level of frustration that exists among Aboriginal organizations and Aboriginal communities about what has been accomplished under the Inherent Right Policy. Moreover, a number of inefficiencies in both the negotiation and implementation processes have been identified, many of which are currently being addressed by AANDC.

An Audit of the Implementation of Modern Treaty Obligations was completed in September 2013 by the departmental Audit and Assurances Services. The audit found that the Department had taken significant steps in establishing foundational elements to manage and coordinate the federal responsibilities as outlined within the specific agreements. This included the establishment of the Implementation Management Framework, the establishment of the governance structures and the development of tools and guidance documents to help other government departments fulfill their own obligations. However, to strengthen the effectiveness of the governance structures and to support and manage the implementation of the federal obligations, the audit identified opportunities to improve key elements of the Implementation Management Framework, including designing formal responsibilities and business processes for proactive monitoring of the status of federal obligations, establishing foundational elements of the regional caucuses and developing formal orientation materials for new members of the oversight bodies representing the federal governance structure.

1.3 Objectives and Expected OutcomesFootnote 5

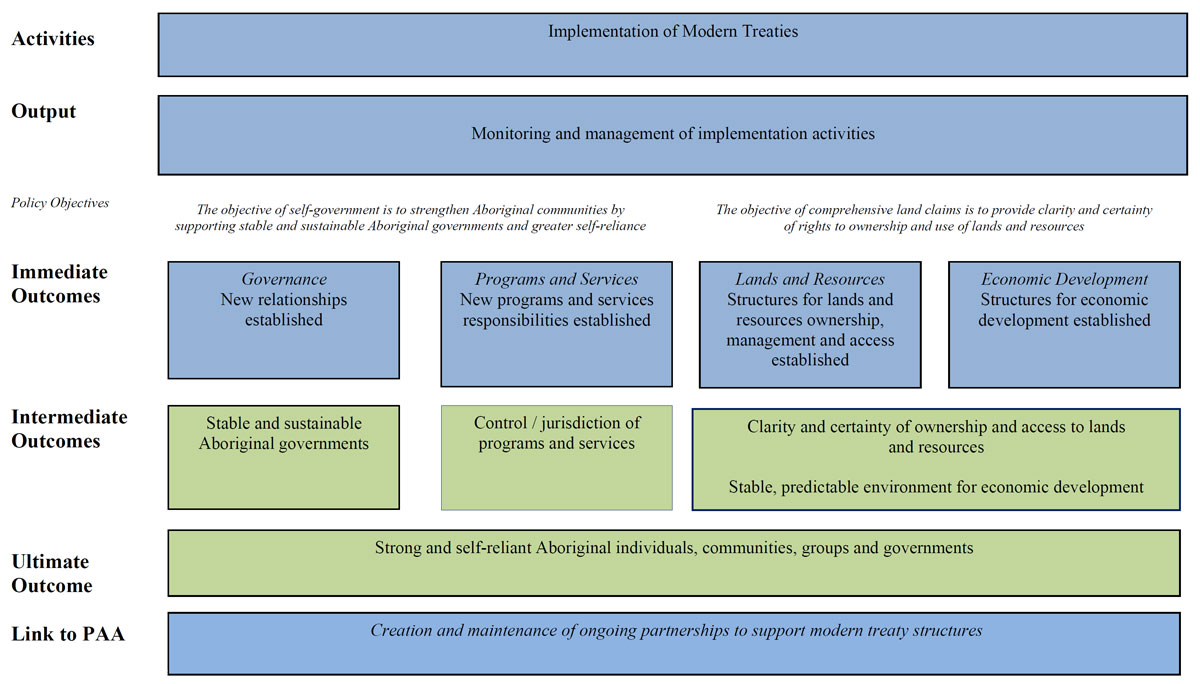

Description of 1.3 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

This image displays the Logic Model for measuring the impacts of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements, as presented in AANDC's Performance Measurement Strategy.

The image is in the form of a chart which shows "Activities" at the first level – the Implementation of Modern Treaties, flowing into "Outputs" – the Monitoring and management of implementation activities.

"Outputs"flow into "Policy Objectives", which is split into two sides. The first objective is for self-government to strengthen Aboriginal communities by supporting stable and sustainable Aboriginal governments and greater self-reliance. The second objective is for comprehensive land claims to provide clarity and certainty of rights to ownership and use of lands and resources.

"Policy Objectives" flow into "Immediate Outcomes". The first policy objective, splits into two again; (1) Governance – new relationships established and (2) Programs and Services – new programs and services established. The second policy objective splits into (3) Lands and Resources – structures for land and resource ownership established and, (4) Economic Development – structures for economic development established.

"Immediate Outcomes" flow into "Intermediate Outcomes". The "Intermediate Outcome" under (1) Governance is stable and sustainable Aboriginal governments. For (2) Programs and Services it is control / jurisdiction of programs and services. For (3) Lands and Resources and (4) Economic Development it is clarity and certainty of ownership and access to lands and resources, as well as a stable and predictable environment for economic development.

"Intermediate Outcomes" flow into an "Ultimate Outcome". All four areas re-merge into one ultimate outcome; Strong and self-reliant Aboriginal individuals, communities, groups and governments.

"Ultimate Outcomes" link into the bottom level, which is the "Link to the PAA" – Creation and maintenance of ongoing partnerships to support modern treaty structures.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation timing and scope

Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 22, 2012. The evaluation was conducted internally within EPMRB, with component analyses contracted externally to specialists. These include a financial and economic analysis by PRA Inc.; a statistical analysis by Ravi Pendakar; a gender analysis by Cornet Consulting and Mediation; and a literature review by Alderson-Gill and Associates.

The scope of the evaluation includes stand-alone comprehensive land claim agreements and comprehensive land claims with related self-government agreements. Stand-alone self-government agreements were not included in this evaluation.

The evaluation issues of relevance and performance (effectiveness) are included in this evaluation. The evaluation issue of performance (efficiency and economy) was included in the processes of negotiation evaluation, completed in November 2014.

TThe evaluation, though covering all aspects of modern treaties, focused on lands, resources and economic development. An evaluation of self-government, taking place in fiscal year 2014-15, will further assess the impacts related to governance and programs and services.

2.2 Evaluation methods

Evaluation methods used in this evaluation include:

Document/Literature Review

Review of Memoranda to Cabinet documents, Treasury Board submissions, data collected through the performance measurement strategy, previous evaluations and audits (internal and Office of the Auditor General audits), internal documents related to performance of modern treaties (such as mandated agreement reviews, subject specific reviews, annual reports), AANDC policy and performance reports. Literature review, which focused on documents related to impacts of modern treaties.

Key Informant Interviews

A total of 38 key informant interviews were conducted with representatives from the following groups:

- AANDC Headquarters (n=18). Sectors – Treaties and Aboriginal Governments, Lands and Economic Development, Northern Affairs.

- AANDC Regional Offices (n=5). Regions – Atlantic, Quebec, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon.

- Other Government Departments (n=8). Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, Natural Resources Canada, Parks Canada, Environment Canada, Canadian Heritage, Health Canada, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada.

- Provincial and Territorial Governments (n=4). British Columbia, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Yukon.

- Northern Regulatory Bodies (n=3).

File Review

A file review was conducted to assess the extent to which each agreement was aligned with policy objectives and established structures to support the intended outcomes. Information for the file review was based on government approval documents, the final agreements and any associated side agreements (e.g. a fiscal financing agreement), implementation annual reports and any publically available information such as a public registry of laws for an Aboriginal signatory group. The file review was also informed by consultation with AANDC Implementation Branch representatives for each file. The review included the following 10 final agreements:

- Inuvialuit

- Nisga'a

- Tsawwassen

- Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in

- Gwich'in

- Nunavut

- Labrador Inuit

- James Bay and Northern Quebec

- Tlicho

- Sahtu Dene and Métis.

Legal Landscape

An analysis of the legal landscape was conducted to inform how the legal landscape related to modern treaties has evolved, the extent to which settling claims affects litigation related to Aboriginal rights, and the legal benefits to the Crown that result from settling claims.

Financial and Economic Analysis

A financial and economic analysis was conducted to assess the extent to which modern treaties have contributed to their intended outcomes from an economic perspective. This involved comparing the structures established through the agreements with existing economic development theory to establish the plausibility of achieving the intended outcomes. The Inuvialuit Final Agreement was then selected to conduct an in-depth analysis on observed economic trends. Publically available data (such as Census data and data from the Inuvialuit indicators project) and financial data provided by the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation were analyzed to determine how the agreement has effected Inuvialuit participation in the economy. The analysis included a group interview with representatives from the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation.

Statistical Analysis

An analysis was conducted to assess the contribution that individual agreements are making to the achievement of the intended long-term outcome by analysing selected economic, social and cultural indicators. The analysis draws on special tabulations drawn from the 2006 Census data and focuses on the Aboriginal identity population living in 113 Census subdivisions affiliated with one or more modern treaties.Footnote 6 This data was compared to the Aboriginal identity population and the non-Aboriginal population.

The Aboriginal identity population was chosen as the key group of interest over the registered population for a number of reasons. First, although everyone who is registered is considered to identify as Aboriginal, not all persons who identify are registered. Inuit, for example, are not registered. Second, choosing the identity population as the secondary comparison is also more reasonable because they are represented in more regions than the registered population.

Contingent Liability Analysis

The contingent liability analysis involved a review of amounts reported as contingent liabilities for the fiscal periods from 2003-04 to 2012-13 to assess the impacts of settling, or conversely not settling, claims on the contingent liabilities of the Crown. For this analysis, two interviews were conducted with AANDC representatives involved in the reporting of contingent liabilities related to modern treaties.

Gender Analysis

In line with the AANDC Gender-based Analysis Policy, an assessment of gender impacts related to modern treaties was conducted. The analysis included a review of relevant literature on issues related to gender participation in negotiations and decision making, protection of equality rights, matrimonial real property, and participation in traditional cultural and economic activities.

It also included five key informant interviews with representatives from AANDC and two interviews with the Assembly of First Nations. In addition, the analysis involved a detailed analysis of the following four agreements:

- Inuvialuit Final Agreement

- James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement

- Nisga'a Final Agreement

- Teslin Tlingit Council

2.3 Quality Assurance

The evaluation was directed and managed by EPMRB in line with the EPMRB’s Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process. Quality assurance was provided through the activities of the working group and an advisory group comprised of representatives from the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector, Implementation Branch, Policy Development and Coordination Branch; Policy and Strategic Direction Sector, Planning Research and Statistics Branch; and Legal Services.

2.4 Considerations and Limitations

Considerations

- There is no requirement under modern treaties for an Aboriginal signatory group to participate in performance measurement and evaluation processes. Therefore, there is currently a reliance on periodic evaluations, in which Aboriginal signatory groups agree to participate, to support performance measurement and evaluation in the context of modern treaties.

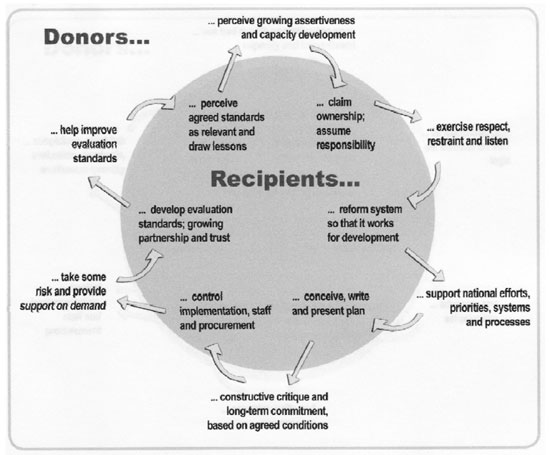

- AANDC engaged the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation to participate in the evaluation process. AANDC's vision is to conduct performance measurement and evaluation work with Aboriginal signatory groups with the expectation that this level of heightened engagement will allow parties to articulate their interests and target performance measures and evaluation work to meet their own specific needs and the needs of all parties.

Limitations

- Limited ongoing performance data related to all aspects of the logic model were available. This included data from the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System, which was not available at the time of the evaluation, and limited baseline data for use in comparing with current measures of progress.

- Statistical analysis was limited to an analysis of the 2006 Census and Household survey. The Community Well-Being index was not used as part of this study as this index, as it is currently designed, does not lend itself to being applied to modern treaties since it captures a high percentage of non-Aboriginal persons.Footnote 7

- Census data for Aboriginal communities is more affected by Statistics Canada confidential guidelines than for other communities because Aboriginal communities tend to be small and the working population is lower. Therefore, Census rounding procedures and confidentiality rules can affect data quality.

- Statistical analysis was based on data pertaining to beneficiaries who live in the treaty settlement area and did not include beneficiaries who resided away from the treaty settlement area.

- One Aboriginal signatory group participated in the evaluation process though the methodology anticipated having three signatory groups participating.

3. Relevance

The significance of modern treaties to Canada's political, cultural and socio-economic landscape cannot be overstated. The rights and obligations of the parties are given important legislative recognition and are legally enforceable. The agreements are given further legal effect through implementing legislation. Many of the agreements are constitutionally protected under Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 (hereafter "s.35"). Once an agreement is signed and brought into effect, a new phase begins for the parties, one which focuses on implementing the many provisions contained in the agreement. This is not a passing phase, but rather an enduring one, marking a new relationship among the parties.

3.1 Alignment with Government Priorities and Program Alignment Architecture

AANDC negotiates and implements modern treaties on behalf of the Government of Canada, with other federal departments being involved where agreements include their areas of responsibility or jurisdiction. The implementation of modern treaties is an important contributor to AANDC overarching mandate and currently one of the Department's priority areas.Footnote 8

During the Crown-First Nations Gathering in January 2012, Canada and the Assembly of First Nations identified treaty implementation as an immediate area for action. The Government of Canada in the 2013 Speech from the Throne stated that it would continue its dialogue on the treaty relationship and comprehensive land claims.

Implementation of modern treaties is situated within the departmental Program Alignment Architecture under the Government Pillar and the Treaty Management Program Activity as shown in Table 2.

| Name | Strategic Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| Pillar | Government Pillar | Good governance and co-operative relations for First Nations, Métis, Non-Status Indians, Inuit and Northerners |

| Program Activity | Treaty Management | Creation and maintenance of ongoing partnerships to support historic and modern-treaty structures |

| Sub-Activity | Implementation of Modern Treaty Obligations | Canada honours all of its obligations as set out in final agreements |

| Management of Treaty Relationships | Improved relations between Canada and Aboriginal entities created to support treaties | |

The 2013-2014 Report on Plans and Priorities identifies specific ways in which the Department is aligning its actions with the strategic outcome. These include:

- Creating and maintaining ongoing partnerships to support relationships and structures by, as an example, leading federal government representation on implementation committees and collaborating with all signatories to fulfill Canada's obligations and to make progress on mutual goals.

- Continuing to coordinate and administer financial arrangements with respect to comprehensive land claim agreements and self-government agreements through the administration, review and renewal of Fiscal Financing Agreements and transfer expenditures to First Nations.

- Continuing to table Annual Reports in Parliament on the activities of the signatories to comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements.

- Providing training to other government departments and ensuring the accuracy of the data to increase the use of the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System and CLCA.net.

3.2 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Since 1982, Aboriginal rights and treaty rights have achieved constitutional protection. They cannot be unilaterally extinguished by the Crown and can only be surrendered with the consent of the collective.Footnote 9 Relying on s.35, the Supreme Court of Canada has developed the jurisprudence by articulating a legal framework that is premised on a purposive approach to the interpretation and application of s.35 and which is supported by a core principle, the honour of the Crown. The primary purpose of s.35, as identified by the Supreme Court of Canada, is the reconciliation of Crown sovereignty with existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. The core principle of Aboriginal law is honourable Crown conduct in relation to Aboriginal and treaty rights in ways which advance "the honourable process of reconciliation demanded by s.35"Footnote 10 and demonstrates an effort to "treat aboriginal peoples in a way ensuring that their rights are taken seriously."Footnote 11

There currently exists a very complex and shifting legal and constitutional framework. Legal developments, starting with Calder,Footnote 12 Delgamuukw,Footnote 13 Van der PeetFootnote 14 and Sparrow, but particularly since the Haida and Taku RiverFootnote 15 decisions in 2004, have changed the nature of the relationship with Aboriginal peoples, including Aboriginal expectations. These developments in the jurisprudence suggest that the federal Crown should consider Aboriginal views in developing its vision of the Crown/Aboriginal relationship. Post-Haida, Taku River and Mikisew Cree,Footnote 16 the provinces, as the governments with the largest interests in land and resources have demonstrated an interest in becoming active players and partners, with new ideas and approaches for addressing s.35 rights without full and final settlement treaties.

The courts, however, continue to emphasize that s.35 rights are best addressed by effective negotiation processes designed to protect a way of life and preserve distinct Aboriginal cultures.Footnote 17 The implementation of these negotiated agreements therefore remains an important component of the overall Crown/Aboriginal relationship.

3.3 Continuing Need

Once modern treaties are settled, there is a risk for a contingent liability to arise due to implementation issues, such as an Aboriginal signatory group filing a claim against the Crown for alleged non-fulfilment of the terms of the agreement. For example, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. filed a statement of claim against the Government of Canada in 2006, asserting that the Government of Canada stands in violation of its contract and fiduciary obligations arising from the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. The relief sought by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. on behalf of the Inuit includes $1 billion in damages, costs and unspecified punitive damages.

There has been ongoing criticism of Canada's approach to the implementation and interpretation of modern treaties by Aboriginal groups, the federal Auditor General and the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal people.Footnote 18 A perceived failure by Government to implement treaties can also add to an already difficult task of negotiating treaties. It acts as a further disincentive for Aboriginal groups with outstanding Aboriginal rights claims from continuing in or entering into the treaty process, thereby, ultimately creating an additional challenge to the management of s.35 rights through treaties. The 2011 Office of the Auditor General of Canada Status Report however found improvements in the overall implementation of modern treaties.Footnote 19

There is a continuing need for clear, unambiguous agreements and close monitoring of the implementation of these agreements in order to mitigate legal and contingent liability risks as well as ensuring ongoing positive working relationships with treaty partners.

4. Performance - Legal, Economic, Social and Gender Impacts

Legal, economic, social and gender analyses were completed in order to assess the impacts of modern treaties from these perspectives.

4.1 Legal Landscape

Where modern treaties have been concluded and properly implemented, they have reduced Aboriginal rights litigation with the particular treaty Aboriginal groups. Other factors have also contributed to reduced litigation, such as having a process in place to negotiate modern treaties. However, modern treaties have failed to reduce other forms of s.35 litigation with the same treaty group or with other Aboriginal groups.

Understanding why is a complex mix of legal and policy considerations. Arguably, modern treaties give rise to new source of s.35 litigation. The reality is that with the evolving jurisprudence, litigation in relation to Aboriginal rights and title has generally declined, having being replaced in large part by more responsive and cost-efficient litigation founded on principles such as the duty to consult. Duty to consult litigation is occurring where groups assert overlapping rights in relation to treaties being negotiated. It can also occur post-treaty when an Aboriginal signatory group perceives that planned government conduct adversely impacts on their new modern treaty rights. Additionally, Aboriginal groups are litigating in relation to government's conduct in negotiating, interpreting and implementing modern treaties, relying upon their understanding of the Supreme Court of Canada decisions, which have highlighted the importance of honour of the Crown, reconciliation and good faith negotiations in the overall Crown/Aboriginal relationship.

Although arguably not capable of achieving the same certainty and finality that government initially anticipated, modern treaties play an important role in placing the Crown/Aboriginal relation on a stronger legal foundation by providing greater continuity, transparency and predictability for the Crown/treaty Aboriginal group relationship. Properly implemented, these agreements advance reconciliation and provide a sound legal foundation for Aboriginal communities to advance their socio-economic interests and aspirations. With treaties giving greater clarity to an Aboriginal group's rights to land, resources, co-operative management and self-government powers, the Aboriginal treaty group is more empowered to govern itself and respond to and improve its own socio-economic conditions and interests through more accountable government. More clearly articulated, s.35 rights in modern treaties also offer the Crown and third parties far greater certainty and predictability in relation to those rights and the agreed upon Crown obligations, including its consultation obligations, in relation to those rights. In this way, the Crown and third parties have a better appreciation of the nature, scope and content of an Aboriginal signatory group's modern treaty rights and corresponding Crown obligations related to those rights.Footnote 20

The Supreme Court of Canada has repeatedly confirmed the importance of modern treaties in advancing the process of reconciliation.Footnote 21 It has also confirmed that an important outcome of modern treaties is providing greater clarity for Aboriginal groups' property and governance rights and the obligations of each of the parties to the treaty, and has indicated that some judicial deference should be paid to the terms the parties have agree to through complex negotiations.Footnote 22 To the extent that treaties are concluded and properly implemented, they advance those objectives.

Until recently, the focus has been on reaching treaty settlements. More attention is now being given to the proper interpretation and implementation of these arrangements, including a corresponding increase in litigation in these areas. The reasons for this shift are understandable. While it is not difficult to interpret and implement initial obligations such as land and capital transfers, it is proving more challenging to meet ongoing requirements that are less concrete. Different views between Aboriginal groups and Canada exist on the approach to be applied to the interpretation and implementation of modern treaties. Since 2008, AANDC has attempted to improve the policy, processes and structures in place to implement modern treaty obligations in response to legal developments, litigation pressures and criticism from Aboriginal organizations as well as the Auditor General and the Senate Sanding Committee on Aboriginal Peoples.

The Supreme Court of Canada appears to regard modern treaties as more akin to a new and evolving relationship that will need to be nurtured and advanced through the lens of the foundational principles.Footnote 23 Since 2008, AANDC has made important efforts to strengthen implementation policies and procedures in an effort to be more responsive to legal developments and litigation pressures. The Implementation Change Agenda has been its primary response. It recognizes the important linkages between proper treaty implementation and obtaining certainty for land and resource use and development, as well as advancing the health and socio-economic circumstances of treaty beneficiaries.Footnote 24 It attempts to ensure a whole of government approach.

These efforts are generally responsive to the courts directions, however, there is a continuing need to implement this agenda across government and to continue to identify outstanding issues. The extent to which federal government policies and practices can demonstrate responsiveness to the Courts pronouncements, the more likely those policies and practices will be able to manage legal risk in this area and limit future unfavourable developments in jurisprudence.

4.2 Economic Impact

The economic literature examined as part of the evaluation identified a number of mechanisms through which modern treaties could affect economic development. To begin, the formalization of property rights helps individuals and collectives derive full benefits from the ownership of resources. In addition, this formalization allows for the maximization of gains from trade and supports other transactions in the economy. Although informal property rights could support similar mechanisms, there is a clear advantage to the formal property structure established under a modern treaty.

In addition to establishing stable property rights, the agreements provide for direct capital transfers to beneficiary organizations. These have the potential to support investment activity, as well as social and educational initiatives with possible long-term economic benefits. Much of the transfer funding is provided to corporate bodies, which, in and of themselves, have the potential to facilitate economic development through their actions.

All the while, governance appears to be closely linked to economic development activity as a stable and separate governance structure encourages economic activity. A variety of activities can help promote effective community governance and effective cooperative federal activity. This appears particularly important given that this cooperation appears to be well entrenched in the approach to modern treaties.

Governance

A critical point coming out of discussions of economic development is that governance can play an important role in facilitating and sustaining economic growth. In their discussion of Aboriginal policy in the United States, Cornell and Kalt point to the importance of the stable governance environment in order to facilitate economic activity. As they suggest, investors from both within and outside of the community have an interest in seeing a stable political environment where government and economic activities remain separate,Footnote 25 as well as an environment that sees political rent seeking - or redistributing economic benefits without engaging in productive activities - kept to a minimum.Footnote 26

Other authors have also noted that the legal framework for financial management at the community level is important. Raybould notes that this may help avoid financial mismanagement and the loss of assets. This, he notes, is a particularly undesirable result given the efforts needed to unlock the value of Aboriginal assets such as land through mechanisms like modern treaties.Footnote 27

Raybould also states that politicians, both federal and First Nation, need to show strong leadership and imaginative resolve. It is the Government's responsibility to work with First Nation leaders with a clear vision of what is being attempted. This is fundamental for the achievement of economic success.Footnote 28 Such a coherent vision can help the economic development process. This argument is consistent with many of the others authors regarding certainty and its impacts on investment and development. For example, when a community or region establishes where to invest capital and how to support economic development activities through education, infrastructure etc., it provides a signal about the development direction of the community or region. Knowing this direction is important to investors who may be planning for long-term business ventures in these areas. It also ensures that development activities are not working at cross purposes.

There is by no means consensus on the nature of good governance at the community level. However, through their research into the nation-building approach to economic development in the United States, Cornell and Kalt identify a number of important characteristics. These include the following:

- "Governing institutions have to be stable. That is, the rules don't change frequently or easily, and when they do change, they change according to prescribed and reliable procedures.

- Governing institutions have to separate politics from day-to-day business and program management, keeping strategic decisions in the hands of elected leadership but putting day-to-day management decisions in the hands of managers.

- Governing institutions have to take the politics out of court decisions or other methods of dispute resolution, sending a clear message to tribal citizens and outsiders that their investments and their claims will be dealt with fairly.

- Governing institutions have to provide a bureaucracy that can get things done reliably and effectively."Footnote 29

At the same time, they point to the need for good governance activities on the part of non-Aboriginal governments as well. Their cooperative nation building approach emphasizes the following role for external governments:

- "A programmatic focus on institutional capacity-building, assisting Native nations with the development of governmental infrastructure that is organized for self-rule, respects indigenous political culture, and is capable of governing well.

- A shift from program funding to block grants, thereby putting decisions about priorities in Indian hands.

- The development of program evaluation criteria that reflect the needs and concerns not only of funders but of Native nations as well.

- A shift from consultation to partnerships in which Native nations and outside governments make joint decisions where the interests of both are involved.

- Recognition that self-governing nations will make mistakes, but what does sovereignty mean if not the freedom to make mistakes and learn from them?"Footnote 30

With that said, it is difficult to identify precisely a relationship between governance and the possible economic development benefits of modern treaties in a general sense. As the discussion above suggests, it is not presence or absence of governance itself that seems to result in effective economic development. Rather, there are specific governance features, present in some communities and not in others, that facilitate success. Modern treaties include provisions meant to support specific elements of good governance. However, given the flexibility in their implementation, it is difficult to argue with certainty that these provisions will necessarily result in specific economic development outcomes. The causality linking governance and economic development is diffuse and complicated.

Economic Development

The economic rationale for modern treaties rests on a considerable amount of development literature. Many authors have suggested how changes to regional economies can result from these agreements based on the provisions outlined therein. For example, certain authors have argued that modern treaties provide a means of formalizing property rights and, by extension, affect the economy. However, prior to discussing the effects of modern treaties on the economy, it is important to note that a diversity of opinions regarding the appropriateness of Aboriginal economic development approaches exists. Two major views pit neoliberal policy approaches against more traditional and collectivist approaches to development.

As Taylor and Friedel note, neoliberal policy places a development focus clearly on the individual. Under this perspective, exclusion from the formal economy is tied closely to a lack of human capital. Individuals fail to participate in the economy because of a lack of necessary skills or available opportunities, and little focus is placed on the historical context in which this exclusion developed.Footnote 31 Under the approach, the integration of individuals into the paid economy remains the principal focus.

Taylor and Friedel note that this approach may have inherent difficulties in an Aboriginal context. In particular, the individualistic nature of the neoliberal development approach may run contrary to established cultural beliefs. For example, communal ownership does not feature prominently in the neoliberal perspective. As the authors note, this makes it difficult to maintain the legitimacy of this cultural perspective while pursuing development goals.Footnote 32

Taylor and Friedel go on to note that this conflict has important implications for development policy. Although potentially successful in achieving the goal of economic integration, certain policies may serve to undermine social and cultural structures in Aboriginal communities where beliefs do not align with the characteristics of a neoliberal development approach.Footnote 33 With this in mind, other authors such as Raybould suggest that establishing a vision for how development should proceed forms an important part of the community's overall approach — and requires considerable thought and discussion.Footnote 34

Property Rights Mechanisms

Many cite the formalization of property rights as the main mechanism through which modern treaties are expected to affect the economy. Prior to discussing these impacts, however, it is important to understand what one means by property rights in an economic context. PrasadFootnote 35 draws on two definitions of property rights in order to highlight important features of the concept. In one case, the author presents a concrete definition based on the work of Furuboton and Pejovich suggesting that property rights involve sanctioned behavioural relations regarding the use of a good.Footnote 36 Effectively, rights allow individuals to use a good in the way that they see fit. In the second case, drawing on the inherent utility associated with goods, Prasad discusses the definition posited by BromleyFootnote 37 where property rights are defined as a claim to a protected stream of benefits.Footnote 38

As early as the 1960s, Coase discussed how the assignment of property rights can affect economic efficiency.Footnote 39 From the work of Prasad, it is possible to see how well-defined property rights can result in an efficient allocation of resources in a competitive economy.Footnote 40 In fact, neoclassical economic theory often assumes rather than empirically verifies that such well-defined property rights exist, positing four key characteristics from the work of TietenbergFootnote 41:

- Universality – This suggests that all resources are privately owned and ownership is completely specified.

- Exclusivity – This means that all benefits accrue to the individual owning the resource and only this individual.

- Transferability – This characteristic states that ownership may be transferred voluntarily from one individual to another.

- Enforceability – This characteristic suggests that property may not be involuntarily seized or encroached on by others.

In many instances, these ideal characteristics do not reflect economic reality. Besley and Ghatak,Footnote 42 for example, identify a number of situations where one or more of the characteristics above fail to hold. They note that in the case of communal property, individuals have use rights but may not exclude others from use. In other circumstances, such as with the prohibition of slavery, they suggest that the establishment and transfer of property rights may be completely circumscribed. More commonly, only certain uses of property are regularly prohibited — for example, the use of land for illegal endeavours.Footnote 43

As the authors note, the failure of these four characteristics to hold in all circumstances points to the importance of understanding the specific features of property rights in a given setting. The differences may drive variation in ownership structures, wealth distribution, and consumption. More importantly, perhaps, they may also affect production and the evolution of the economy over time.Footnote 44

In their work, Besley and Ghatak attempt to itemize separate mechanisms through which variations in property rights may affect economic activity. They identify four such mechanisms as critically important:

- Deriving full benefits from ownership – In this case, insecure property rights may result in the loss of benefits that individuals normally derive from ownership. For example, an individual may lose some or all of their ownership benefits if the property is expropriated.

- Incurring costs of property protection – Simply put, insecure property rights results in the need for protection of ownership claims. These costs directly reduce the potential benefits that may be derived from ownership.

- Deriving gains from trade – In this instance, the inability to transfer property rights means that certain resources may not be put to their most productive use. This results in inefficiencies in the economy as resources are used in inefficient ways.

- Using property to support other transactions – In this final case, secure property rights allow individuals to use resources as collateral during other market transactions. A clear example involves mortgaging property in order to support investment activity.Footnote 45

All of these mechanisms appear to be very important in the context of modern treaties. To begin, deriving full benefits from ownership is important from two different perspectives. From the Aboriginal perspective, expropriation is a — if not the — principal concern motivating modern treaties. Modern treaties represent a formal reaffirmation of ownership rights that signatory groups have consistently identified as their own. This formal reaffirmation therefore limits the ability of government, private organizations, and individuals to expropriate this land and allows beneficiaries to derive full benefits from its use.

From the perspective of non-Aboriginal investors and businesses, direct expropriation of property may not be of principal concern. However, the potential cost of ownership disputes certainly is. Unlike expropriation, which eliminates the benefits one may derive from ownership entirely, disputes and their resolution simply erode economic gains. This is because they represent an additional cost during production. The point is highlighted by Woodruff, where he discusses how formal ownership structures may lower the costs of economic activities. He states that formal ownership eliminates the need to negotiate access to land and other resources on a variable and case-by-case basis.Footnote 46

However, even in contexts where formal property rights exist, disputes may arise about the particulars of ownership. This may involve, for example, extent of land use implied by these rights. Resolving these disputes when they do occur can be costly and as a result impact negatively on economic development. The resolution process outlined in modern treaties provides a formal means of resolving these disputes, thereby reducing these resolution costs.

Modern treaties also have a link to the costs of property protection. Again, from the perspective of Aboriginal groups, who historically did not transfer land ownership or use rights, the use of traditional lands by non-Aboriginal groups without consultation or compensation represents expropriation. Attempts by Aboriginal groups to participate in decision making and derive benefits in these situations represent the direct protection of traditionally-acknowledged property rights. However, these attempts come at a direct cost to participating groups. By formalizing ownership rights, modern treaties eliminate the ongoing need for these protective activities.

The stability afforded by these formal ownership structures is also important in many of the regions covered by modern treaties. Often, economic activity is dominated by primary resource extraction and related activities. Many of these endeavours involve long-term planning and significant investments. The decision to invest in such activities rests in part on having a clear sense of the benefits that one may derive, and the risk of unforeseen losses. The stability of ownership and use rights afforded by modern treaties can allow firms to make accurate projections of their potential returns on investment.

When it comes to deriving benefit from trade, it may appear that the provisions of many modern treaties limit this potential by circumscribing the sale of Aboriginal land. This would seem to imply that the potential benefits gained from trade in these lands would be lost. However, from the discussion above, it is possible to see that the transfer of property rights need not include only sale. The transfer of use rights may involve the establishment of leases or rental agreements in order to allow non-Aboriginal groups to use property identified in the agreements. This, in turn, would allow for the efficient use of resources even when these uses are not undertaken by signatory organizations themselves. Without a clear ownership structure, this type of transfer would be impossible.

The effects of formal ownership on the ability to use property to support other transactions have been well documented in economic literature. For example, in his discussion of The Mystery of Capital, Woodruff outlines one of de Soto's main arguments regarding the relationship between formal property ownership and economic development. He suggests that in situations where property ownership remains informal, individuals cannot leverage property for investment purposes. Effectively, he argues that the value of property cannot be used by much of the population to start a business or other enterprise, thereby limiting economic development.Footnote 47

Although de Soto's argument holds intuitive appeal, its applicability in the case of modern treaties may be limited. This is particularly true given that the agreements provide for collective title as opposed to individual ownership. While formalizing collective title may allow for access to capital among corporations, it would not necessarily provide for individual leveraging and investment.

Informal Verses Formal Rights

Modern treaties outline formal ownership and use rights on the part of signatory organizations, including the Government of Canada. These rights fit within the broader Canadian legal system. With that said, it is important to understand that property rights can exist outside of the formal legal structure. As Clarke notes, other, less formal mechanisms may exist to maintain these rights.Footnote 48 These may involve informal social sanctions levied against those who infringe on collectively understood rights.

In addition, it is also important to understand that even in the absence of stable and well-defined property rights, investments and economic activity may still take place. In situations where potential returns are sufficiently high, the risk resulting from ownership instability may not dissuade entrepreneurs or firms from investing and pursuing economic endeavours. Clarke, for one, points to examples from the reform era in China, where restrictions on economic activity were relaxed, and, despite not having a well-developed formal legal structure to support individual property rights, entrepreneurial activity flourished due to high levels of profit driven by excess demand.Footnote 49

As he also points out, however, comparisons of formal and informal property right structures rest not on whether economic development may take place under either. Rather, they rest on the key question of whether formal property rights provide for more growth than informal agreements.Footnote 50 In addition, it is also important to understand under which circumstances formal property rights may provide the most benefit.

As Clarke notes, the economic literature suggests that informal property right structures, which rest on social sanctions and repeated interactions among economic agents, perform poorly in one particular circumstance. This is when individuals or groups, who are unknown to each other, interact once with no intention of pursuing a future economic relationship. This is because there is no opportunity to impose sanctions during a subsequent interaction.Footnote 51 In this type of situation, formal property rights enforced by a third party — such as through a legal structure — provide a clear advantage over more informal structures.

Direct capital transfer

Direct financial transfers form an important part of modern treaties. This is because access to capital is at times limited in regions covered by the agreements. In this context, transfers become a critical part of the Aboriginal signatory group's economic development approaches. This is true of both general funds provided through the agreement, which may be redirected for investment in the region, as well as funds earmarked for specific activities.

As SakuFootnote 52 notes, the funds provided through modern treaties have been used to pursue a number of investment activities. Citing the Inuvialuit Final Agreement specifically, he points to investments made by the Inuvialuit using these funds both regionally and throughout Canada. They include:

- business purchases;

- investments in oil companies; and

- real estate purchases.

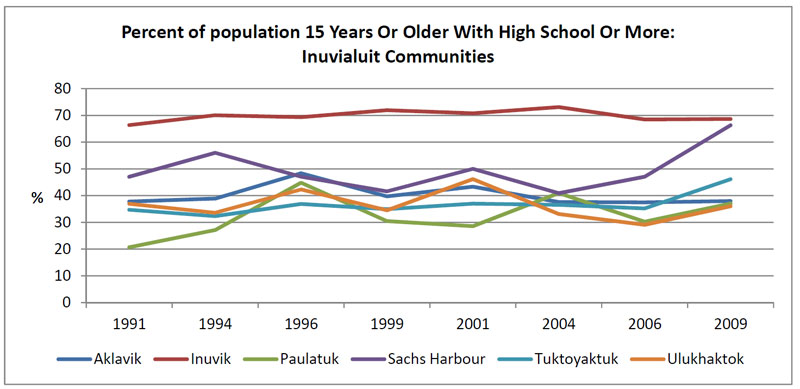

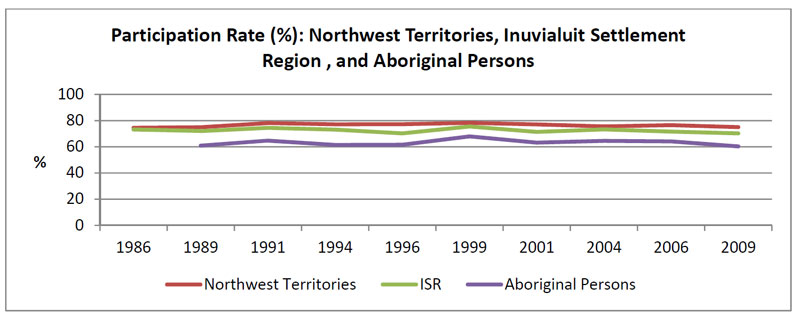

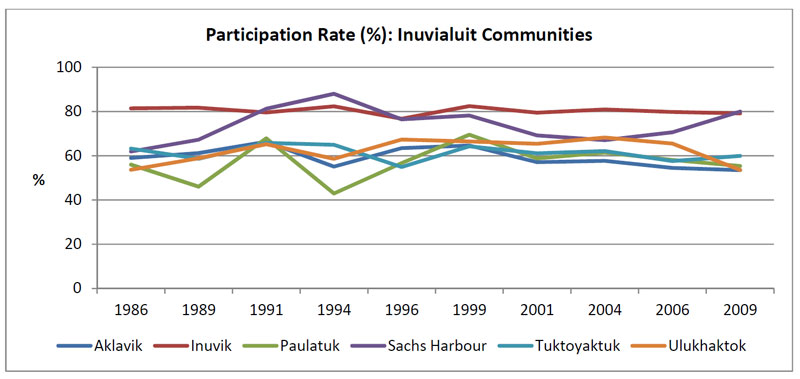

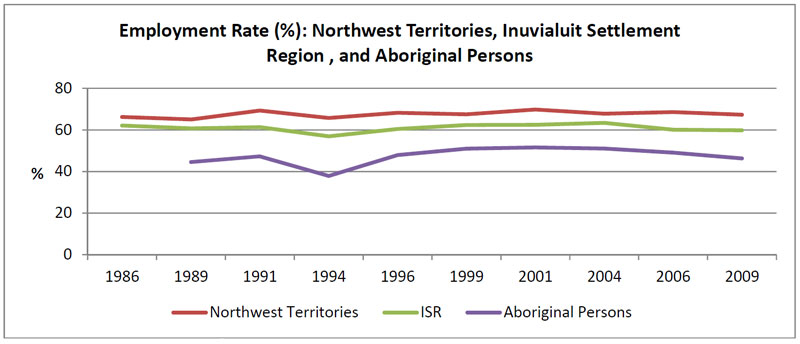

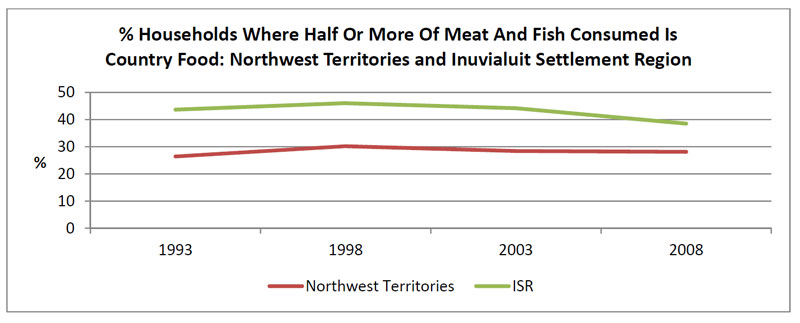

The returns from these investments may then be used regionally to further economic development goals.Footnote 53