Evaluation of the Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative (Protected Areas Strategy)

Final Report

Date: April 2013

Project Number: 10018

PDF Version (539 Kb, 80 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Design and Delivery

- 5. Evaluation Findings - Performance (Effectiveness/Success)

- 6. Conclusion

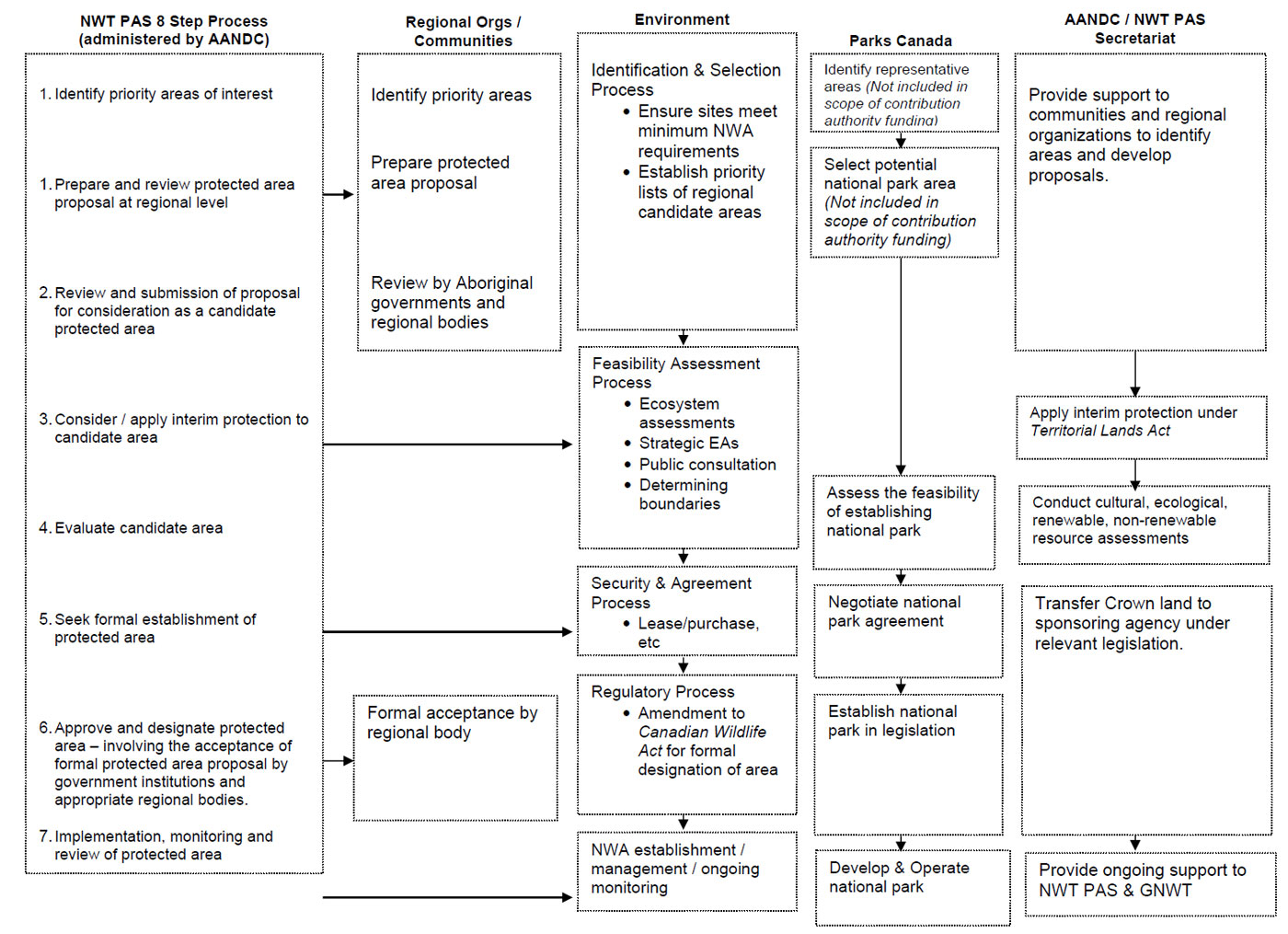

- Annex A: Protected Areas Process Map

- Annex B: Evaluation Matrix: Evaluation of Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories

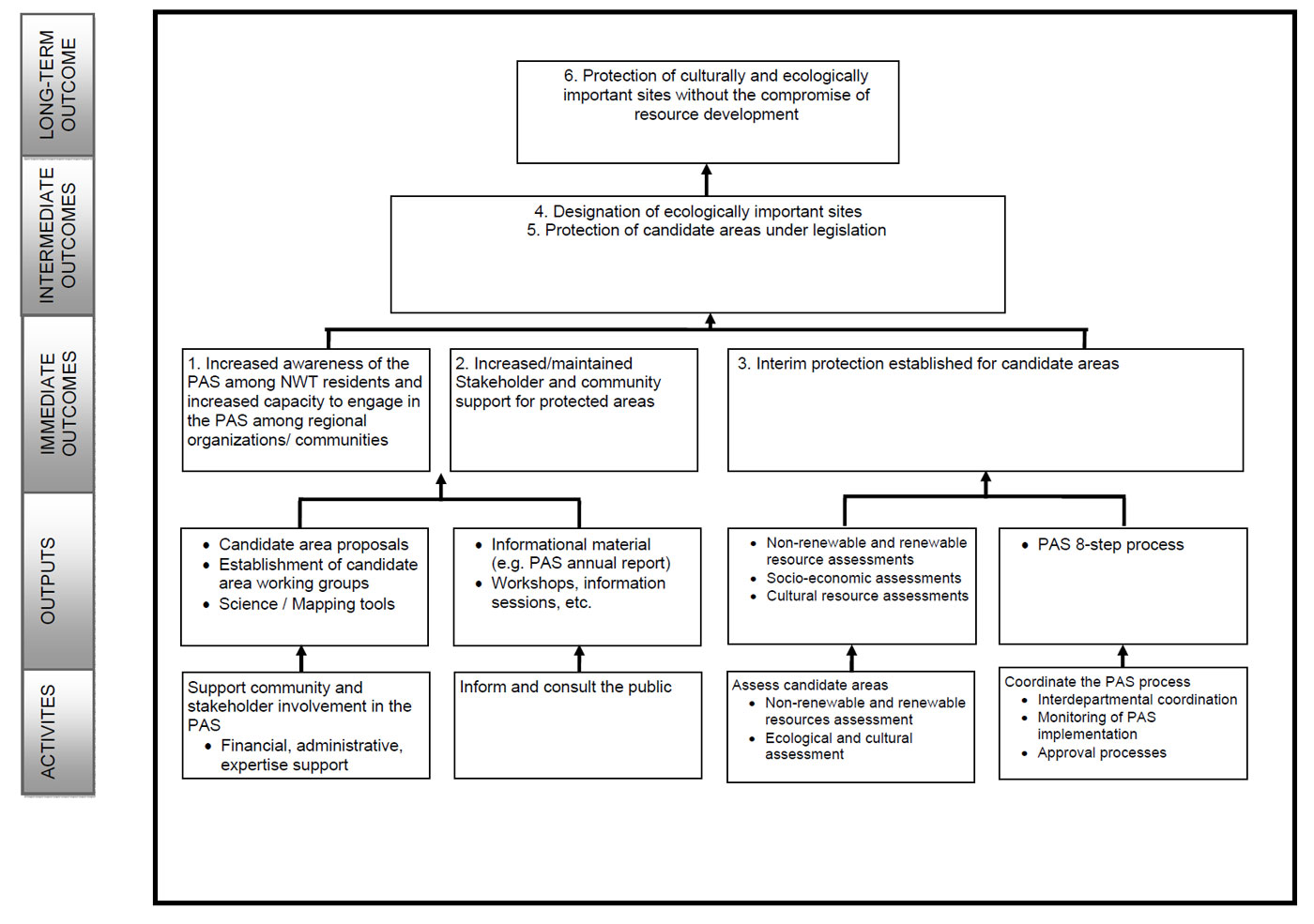

- Annex C: Program Logic Model

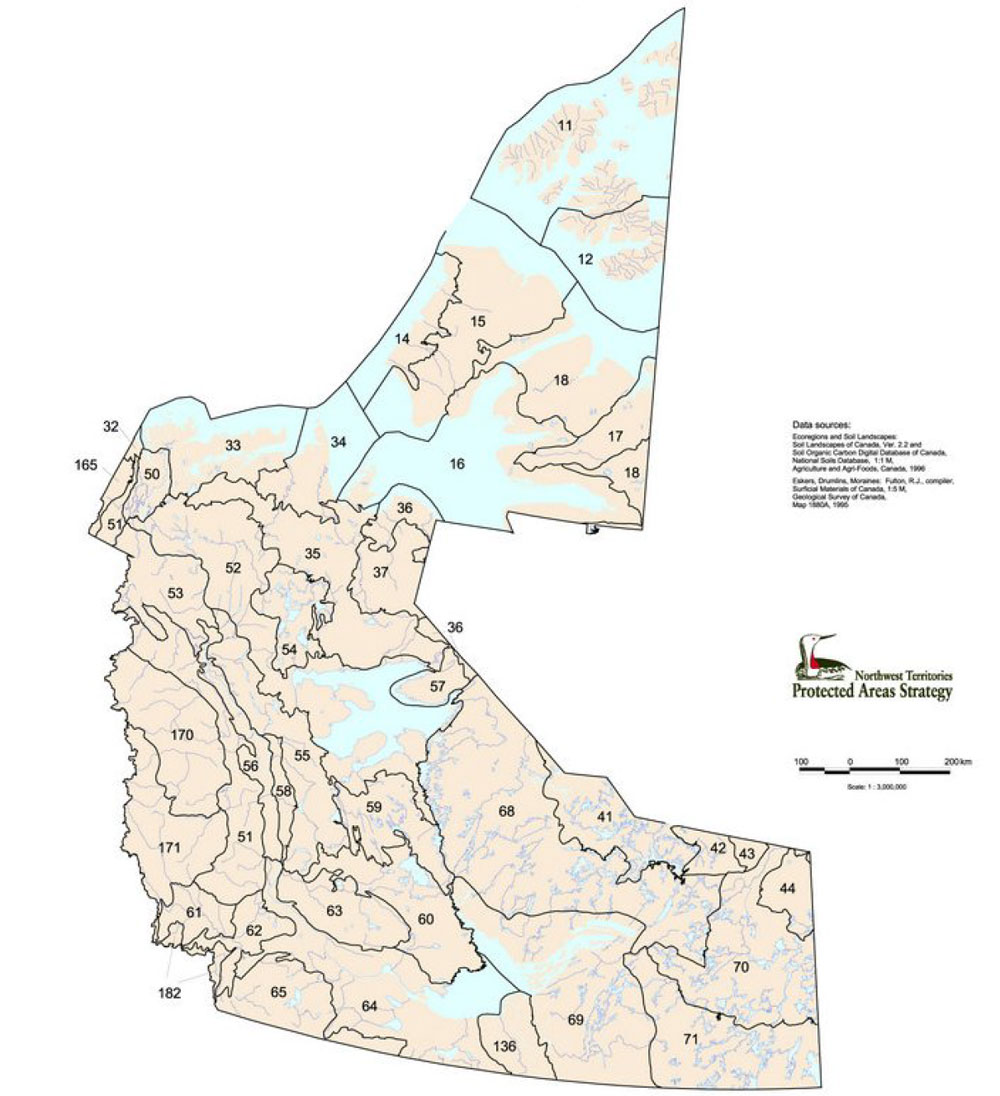

- Annex D: Map of NWT-PAS

- Annex E: Terrestrial Ecoregions of NWT

- Annex F: Bibliography

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| EPMRC |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee |

| LUP |

Land Use Planning |

| NWT |

Northwest Territories |

| NWT-PAS |

Northwest Territories Protected Areas Strategy |

| PAS |

Protected Areas Strategy |

Executive Summary

Evaluation Scope and Issues

This report presents the findings and recommendations of the Evaluation of the Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative. The Initiative supports the Northwest Territories (NWT) Protected Areas Strategy (PAS) and its objectives are to establish, develop and operate up to six federal national wildlife areas; one national historic site; carry out consultation and a feasibility study that could lead to the establishment of a national park reserve (Thaidene Nene); and assist in responsible resource development in support of the NWT's PAS. The evaluation reports on findings from fiscal years 2008-09 to 2011-12 and addresses five core issues outlined in the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation: relevance (continuing need for the NWT-PAS; alignment with government priorities, consistency with federal roles and responsibilities); and performance (achievement of expected outcomes, and demonstration of efficiency and economy). It also addresses design and delivery, best practices, and lessons learned.

Program Background

The NWT-PAS promotes and supports the creation and establishment of a network of protected areas in the NWT. Approved by the Government of Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territory in 1999, it is designed to be both community-based and community-driven. The two principal goals of the NWT-PAS are to protect: (a) special natural and cultural areas; and (b) core representative areas within each eco-region in the NWT. The Strategy's 8-step planning processFootnote 1 and balanced approach to establishing protected areas are its primary guiding principles.

Evaluation's Methodology

The evaluation's methodology consisted of four lines of evidence: (a) literature review; (b) document and file reviews; (c) 29 structured key informant interviews; and (d) two case studies with 11 participants. A total of 40 respondents were interviewed, including officials from AANDC, Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, Government of the Northwest Territories, Aboriginal groups/communities, industry associations and individual resource companies. Limitations included the availability of some participants due to scheduling conflicts.

Key Evaluation Findings

I. Relevance

The evidence clearly demonstrates a continued need for a network of protected areas in the NWT. This is due to: (a) increased interest and activity in economic/resource development in the NWT and its consequent impact on First Nations, wildlife, habitat; and (b) how the Initiative complements regional land use planning. The Strategy is also aligned with Government of Canada priorities (e.g. managing resources, land and environment in the North) and it is appropriately aligned with federal roles and responsibilities (e.g. statutory and regulatory responsibilities related to crown land). However, at the time of writing this evaluation report (December 2012 – January 2013) there was uncertainty with respect to how and to what extent devolutionFootnote 2 of lands and resources in the NWT may impact the Government of Canada's roles and responsibilities with respect to the NWT-PAS.

II. Design and Delivery

The NWT-PAS is appropriately designed to provide the opportunity for stakeholders to meaningfully participate in it, share their interests and priorities, while also building upon relationships. This is largely due to the governance structure's commitment to communication, collaboration and consultation to facilitate the 8-step process that is required to establish and maintain protected areas. However, significant challenges like vertical communication (between the NWT-PAS and senior federal Headquarters officials) and achieving quorum for Steering Committee meetings remain. There is a need to revisit and improve upon the clarity of roles and responsibilities of the Steering Committee and Secretariat and to encourage a stronger understanding of the relationship between the NWT-PAS and marine conservation. There is also a need for the Steering Committee roles and responsibilities to evolve (i.e. provide more strategic direction and advice), specifically in terms of protected area management and monitoring.

With respect to the Strategy's delivery, the Initiative offers stakeholders sufficient financial, technical, scientific and administrative supports to participate in the NWT-PAS process. However, there is a need to improve the mechanisms for financial transfers as they are unpredictable and consequently pose unnecessary administrative burden and creates uncertainty in planning. There is also no evidence of Performance Measurement mechanisms. Mitigating such program delivery issues would improve the Initiative's effectiveness and efficiency.

III. Performance (Effectiveness, Efficiency and Economy)

The Government of Canada has not yet established any of the six mandated national wildlife areas. Approval for the finalization of these sites has been delayed in the approval process. Currently, there is only one established National Historic Site (Saoyú-?ehdacho) under Parks Canada Agency. With respect to Environment Canada, there are four candidate national wildlife areas under interim protection (Edéhzhíe, Ts'ude niline Tu'eyeta, Ka'a'gee Tu and Sambaa K'e) and one awaiting approval (Kwets'oòtł'àà). According to the 2008 Results-based Management and Accountability Framework, the targeted immediate outcome of three additional areas under interim protection in 2011 and up to four more by 2013 has not been achieved.

There is awareness of the NWT-PAS among NWT residents and the Strategy is managed in a way which allows regional organisations and communities to be engaged. Due to a lack of appropriate data, it is unclear if there has been an increase in awareness of the Strategy among NWT residents or in their capacity to participate. At the same time, there is evidence of increased and sustained support for the NWT-PAS from numerous communities and from the majority of stakeholders.

Finally, financial and qualitative data suggest that the NWT-PAS has managed to minimize financial and material resources while optimizing outputs. However, human resource capacity in remote regions and outcomes can be improved through addressing capacity issues at the community level, reviewing the role of the Steering Committee and reviewing current funding mechanisms.

IV. Best Practices and Lessons Learned

The evaluation identified a number of best practices. These include earlier engagement of Aboriginal peoples', involvement in the NWT-PAS process, placing a strong emphasis on multi-stakeholder partnership and collaboration, substantial and active communication efforts through regular Steering Committee and working group meetings, newsletters, etc., and the use of Aboriginal traditional knowledge, which enhances the overall understanding of the culture, history, habitat, etc. of the land.

Evidence suggests numerous lessons learned, including informing stakeholders early on that the 8-step process can be longer than anticipated, clarifying ministerial approval timelines, encouraging stronger communication between NWT-PAS senior federal (Headquarters) government officials (i.e., Assistant Deputy Minister and Deputy Minister); and, clarifying to stakeholders all available land protection options before proceeding with the Strategy.

Recommendations

It is recommended that the participating departments/agencies, in collaboration with each other:

- Address the issue of capacity constraints at the community level by working with the relevant community partners in order to include more expertise and increase capacity in the NWT-PAS activities while sharing costs related to assessments and Working Group activities.

- Revisit and review the role of the Steering Committee to ensure it provides strategic direction as per its mandate.

- In coordination with the relevant departments and agencies, review current funding mechanisms, to ensure predictability of funds and a timely delivery to recipients.

- Develop an approach that will foster better understanding and communication of the NWT-PAS as it pertains to the devolution of lands and resources.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative: Protected Areas Strategy (NWT-PAS)

Project #: 1570-7/10018

1. Management Response

To date, only one of seven protected areas has been permanently created using the federal government's contributions to the NWT-PAS through targeted funding in 2008-09 and beyond. Limited investments in the next year or two should deliver additional results for this initiative because of the analysis and process undertaken to date with wide participation by NWT stakeholders and communities.

As noted in the report, other land conservation mechanisms like land use planning or other conservation processes such as those managed by the Government of Northwest Territories, may also attain similar results to those sought with the NWT-PAS. There is also continued interest in the long-term permanence of parks and national wildlife areas that should continue to be explored with the ongoing funding associated with this initiative.

The scope of the evaluation recommendations were limited to actions that could be implemented within one year of the evaluations' approval, given that devolution will occur at the end of that time frame. The proposed action plans will address these recommendations in order to enable improvements in ongoing federal NWT-PAS activities.

In the context of devolution, what had been AANDC's role in the NWT-PAS will largely become the responsibility of the Government of the Northwest Territories as of April 1, 2014. AANDC will play a lead role in supporting an orderly transfer of NWT-PAS duties and knowledge, including the operation of the PAS Secretariat, to their Government of Northwest Territories counterparts in the period leading up to devolution.

Environment Canada will continue to support the completion of working group reports for candidate national wildlife areas. Environment Canada will also manage and monitor any national wildlife areas that are established. Building on the strong base of protected area analysis and community and stakeholder engagement engendered to this point in time, and based on feedback from this evaluation, the focus of future program activities will be on the completion of working group reports, where such reports have not yet been finalized. From this point, based on decisions by federal and NWT governments, in the context of devolution, the final steps to establish national wildlife areas may be undertaken.

Parks Canada will continue to use ongoing funding to complete the establishment and development of the Saoyú-?ehdacho National Historic Site as agreed to with Sahtu Dene and Métis, and to continue to operate the site. With respect to the Thaidene Nene, Parks Canada will continue to work with other federal departments, the Government of the Northwest Territories, the Lutsel K'e Dene First Nation and the Northwest Territories Métis Nation to achieve a boundary for a national park reserve while respecting devolution. This work of developing and consulting on a final boundary, as well as negotiating the required agreements, will be funded by Parks Canada. Parks Canada will also examine the means to secure the necessary funding to establish, develop and operate the national park reserve as the NWT-PAS program does not provide the necessary funding for this aspect of the Thaidene Nene project.

2. Action Plan

It is recommended that the participating departments:

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Address the issue of capacity constraints at the community level by working with relevant community partners in order to include more expertise and increase capacity in the NWT-PAS activities while sharing costs related to assessments and working group activities. | In the context of devolution ,what had been AANDC's role and ongoing funding in the NWT-PAS will become the responsibility of the Government of Northwest Territories after April 1, 2014. This said, the federal government (AANDC and Environment Canada) will continue supporting this initiative, each department within its area of responsibility and within existing resource levels. | AANDC NWT Regional Director General | Start Date: March 2013 |

| AANDC funding for NWT-PAS related activities is significantly reduced as of April 2013. In the context of their different departmental mandates, AANDC and Environment Canada will work together collaboratively in order to increase participation / expertise and cost-sharing for Working Group meetings involving community members, and will work towards achieving completed reports for all candidate areas. | Environment Canada Prairies & Northern Region, Regional Director and Northern Conservation Service Manager | Completion: April 2014 |

|

| 2. Revisit and review the role of the Steering Committee to ensure it provides strategic direction in order to clarify roles and responsibilities related to ongoing devolution discussions and to ensure adequate partner participation, as per its mandate. | In coordination with Environment Canada and Government of Northwest Territories, AANDC will lead the review of the Steering Committee's Work Plan and Terms of Reference until devolution (April 2014). All options will be examined which could include a new role and mandate for the Steering Committee or the Steering Committee being disbanded if it is deemed no longer needed. Government of Northwest Territories input into changes to the Steering Committee will be paramount as they will be responsible for funding the Steering Committee post-devolution. | AANDC NWT Regional Director General Director Environment Canada Prairies & Northern Region and Northern Conservation Service Manager |

Start Date: April 2013 |

| 1) Initial discussion on changes to the Steering Committee presented during 2013-14 Steering Committee Workplan review at Steering Committee meeting. |

Completion: 1) February 2013 |

||

| 2) Follow-up Steering Committee meeting to discuss the ongoing role of the Steering Committee. | 2) May 2013 | ||

| 3) Decisions made and communicated on the future of the Steering Committee. | 3) April 2014 | ||

| 3. In coordination with the relevant departments and agencies, review current funding mechanisms, to ensure predictability of funds and a timely delivery to recipients. | Start Date: March 2013 |

||

| 1) AANDC funding for PAS activities as of 2013-14 and beyond is significantly reduced, to an extent that it will likely preclude funding of recipients. At the time of devolution, Government of Northwest Territories will take on responsibilities and funding associated with ongoing NWT-PAS activities. Through the Policy on Transfer Payment initiative, AANDC will continue the work to address outstanding concerns regarding predictability of funds and timely delivery to recipients. |

1) AANDC NWT Region Regional Director General | Completion: 1) April 2014 |

|

| 2) Should the proposed Thaidene Nene national park reserve prove feasible, and the necessary agreements are successfully negotiated, Parks Canada will examine the means to secure new funds to establish, develop and operate the Thaidene Nene national park reserve as the NWT-PAS program does not provide the necessary funding for this aspect of the park reserve project. | 2) Parks Canada Agency Director, Protected Areas Establishment Branch | 2) April 2014 | |

| 4. Develop an approach that will foster better understanding and communication of the NWT-PAS as it pertains to the devolution of lands and resources. | Within the context of devolution of lands and resources, AANDC, in coordination with Environment Canada, is currently working with Government of Northwest Territories on developing an approach that will ensure smooth transition and foster better understanding of the NWT-PAS activities and intent post-devolution. So far, the following actions have been completed: | AANDC NWT Regional Director General with support of AANDC Director General of Natural Resources and Environment Branch Environment Canada National Capital Region Protected Areas Manager and Environment Canada Strategic Policy Branch, Prairies and Northern Region |

Start Date: February 2013 |

| Completion: Overall, by April 2014 |

|||

| 1) Correspondence at the Ministerial level between AANDC / Environment Canada / Government of Northwest Territories to clarify / agree on an orderly transition to Devolution. | 1) February 2013 | ||

| 2) Participation in Working Group meetings with common messaging. | 2) March 2013 | ||

| Further joint Environment Canada/AANDC communications will be undertaken leading up to devolution. Parks Canada will work with AANDC and the Government of Northwest Territories on common communication messages regarding Thaidene Nene |

Parks Canada's Director, Protected Areas Establishment Branch AANDC Director General of Natural Resources and Environment Branch |

Start June 2013 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee, on behalf of the three organizations' evaluation teams:

Original signed on October 28, 2013, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch, AANDC

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on August 20, 2013, by:

Janet King

ADM, Northern Affairs Organization, AANDC

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on October 16, 2013, by:

Mike Beale, Environment Canada

ADM, Environmental Stewardship Branch, Environment Canada

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on August 30, 2013, by:

Rob Prosper

VP, Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation, Parks Canada

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of the Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative: Protected Areas Strategy were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This report presents the findings and recommendations of the Evaluation of the Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative in support of the Northwest Territories Protected Areas Strategy (NWT-PAS). The evaluation was conducted in response to the Treasury Board requirement that all direct program spending, excluding grants and contributions is evaluated every five years (Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation, 2009). Throughout this document, the NWT-PAS is also alternately referred to as the "Program," the "Initiative" and the "Strategy."

This horizontal evaluation with Environment Canada addresses 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation requirements. In line with that policy, it examines five core issues associated to the NWT-PAS: relevance (i.e. continuing need for the program, alignment with government priorities, consistency with federal roles and responsibilities) and performance (i.e., achievement of expected outcomes and demonstrated efficiency and economy). The evaluation also looked at design and delivery, best practices, lessons learned and where possible, provides alternatives in order to help inform future similar initiatives and programming.

The Terms of Reference, developed during the planning phase of the evaluation, sets out the scope of the evaluation, which was conducted between November 2011 and November 2012. The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB), in collaboration with the Audit and Evaluation Branch at Environment Canada and Goss Gilroy Inc., initiated the evaluation. The work was completed internally by EPMRB with assistance from Environment Canada and to some extent, Parks Canada Agency. For example, the literature, document and file reviews and the development of the case studies background were conducted by Goss Gilroy Inc. with additional information coming from EPMRB. EPMRB undertook the case studies and a majority of the key informant interviews with some help from Environment Canada, and drafted the final report with input from the evaluation's working group (officials from Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency).

The report is structured as follows:

Section 1.0 – Introduction (including the NWT-PAS' profile, objectives, structure, management, stakeholders, beneficiaries and resources);

Section 2.0 – Evaluation methodology and limitations;

Section 3.0 – Evaluation findings related to relevance;

Section 4.0 – Evaluation findings related to design and delivery;

Section 5.0 – Evaluation findings related to performance (efficiency, economy and effectiveness);

Section 6.0 – Conclusions and recommendations; and

Section 7.0 – Annexes.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

The Northwest Territories (NWT) and the Mackenzie Valley (Valley) in particular, provides numerous opportunities to protect new areas in Canada. The Valley covers a vast area of pristine boreal forest that supports a rich diversity of wildlife, including over 100 species of migratory birds and several species at risk, and contains significant historic sites that document traditional Aboriginal lifestyles and land uses. At the same time, it has potential for non-renewable resource development.

In 1974, the Government of Canada commissioned the Berger Inquiry to examine the social, environmental, and economic impacts of the proposed Mackenzie Gas Project, which would be one of the largest non-renewable resource infrastructure projects in Canadian history. Although the Mackenzie Gas Project is limited to producing and transporting natural gas from the Mackenzie Delta, it is regarded as having basin-opening potential, and would induce new resource exploration and development in other regions of the Valley. This would create unwanted direct impacts in 16 of the NWT's eco-regions; the long-term effects of the Mackenzie Gas Project and related developments may extend to all of its 42 eco-regions. The 1977 Report of the Inquiry concluded that such a pipeline would pose significant risk to the environment and provide few long-term economic benefits to northern communities. Particularly, it raised concerns about Aboriginal peoples, recommending that the Mackenzie Gas Project be delayed 10 years and that any development be preceded by land claim settlements and the establishment of protected areas.

Similar recommendations were made in 1996, when during the environmental assessment of the proposed BHP diamond mine, the World Wildlife Fund threatened legal action against the federal government unless a commitment was made to develop a strategy for protected areas in the NWT. Collaboration among federal and territorial governments, industries, communities, Aboriginal organizations and environmental non-government organizations ensued, resulting in the NWT-PAS in 1999.

The NWT-PAS has two primary goals: to protect significant natural and cultural areas, and to represent each of the NWT's 42 eco-regions. The NWT-PAS sets out an 8-step, community engagement process that utilizes the best available traditional, ecological, resource and economic knowledge to make land use decisions. The 8-steps include: candidate area identification; proposal development; various ecological, social/cultural, economic and resource assessments; management planning; interim and final protection; and ongoing management, monitoring and enforcement activities (see Annex A).

In 2003, the Minister of the then Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada requested that a plan be developed to address concerns that the proposed Mackenzie Gas Project might preclude the NWT-PAS vision of a network of protected areas in the Mackenzie Valley. The result was the Mackenzie Valley Five Year Action Plan – Conservation Planning for Pipeline Development. The Action Plan is subsequent to the NWT-PAS; its aim is designating protected areas ahead of, or concurrently with, pipeline development.

By 2008, three candidate protected areas (Edéhzhíe (Horn Plateau), Sambaa K'e (Trout Lake) and Ts'ude niline Tu'eyeta (Ramparts)) had been proposed through the NWT-PAS but only one, Saoyú-?ehdacho, had achieved permanent protection as a National Historic Site. To pursue a more balanced approach to development and conservation, the Government of Canada decided to provide $25 million over five years and $4 million per year thereafter in Budget 2007 in an effort "to create or expand protected areas in the NWT, supporting the Protected Areas Strategy (PAS)."

The NWT-PAS relies on existing legislation. As a result, only Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency and the Government of the Northwest Territories can sponsor protected areas. There are two imperatives to sponsoring protected areas: the candidate area must fit within the planned results and priorities of mandated programs and there must be an available source of funds to provide for ongoing operations.

1.2.2 Program Objectives/Activities and Expected Outcomes

The Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative supports the NWT-PAS and its objectives are to establish, develop and operate up to six federal national wildlife areas by Environment Canada. This includes establishing one national historic site; carrying out a consultation and a feasibility study that could lead to the establishment of a national park reserve (Thaidene Nene) to be completed by Parks Canada Agency; and assist in responsible resource development in support of the NWT's PAS. AANDC is to provide ongoing support (technical assistance) to the protected areas sponsors (Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency and the Government of Northwest Territories). AANDC also provides coordination and financial support to the PAS Secretariat, and is responsible for land management in the NWT.

Further, AANDC's role is to support the Government of Canada's commitment to assist Aboriginal communities in fulfilling their aspirations for greater self-reliance. AANDC delivers its programs through the following key strategic outcomes: The People, the Government, the Land and Economy, the North, Regional Operations and the Office of the Federal Interlocutor. The Initiative specifically contributes to the North outcome, which addresses the sustainable use of lands and resources by First Nations, Inuit and Northerners in ways that emphasize improved environmental management and stewardship.

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada

As the Department responsible for administering Crown land in the North, AANDC has a number of duties related to the establishment of protected areas in the NWT. These include participating in stakeholder consultation; conducting assessments of candidate areas; putting in place interim land withdrawals; and, transfer of lands to the agency responsible for the protected area.

In partnership with the Government of Northwest Territories, AANDC provides a strategic leadership role, including support to the NWT-PAS Secretariat, which is staffed by AANDC and Government of Northwest Territories officials. The Secretariat is the point of contact for the public and provides coordination, funding, technical and administrative support (provided by AANDC) to communities in the identification of candidate areas and proposal development.

Environment Canada

According to the Initiative, Environment Canada's role in this Strategy is to establish six national wildlife areas. National wildlife areas protect significant habitat that supports wildlife or ecosystems at risk. Environment Canada's legislation is intended to offer communities the type of permanent protection they desire for candidate areas. To date, Environment Canada is working towards establishing five national wildlife areas. The three most advanced sites towards achieving permanent protection are: Edéhzhíe, Ka'a'gee Tu and Ts'udeniline Tu'eyeta. Environment Canada will also continue to collaborate with communities and stakeholders to advance planning efforts so that the public expectation for additional national wildlife areas might be realized in the future.

The NWT-PAS contributes to Environment Canada's strategic outcome, which is "Canada's natural environment is conserved and restored for present and future generations" and it will be achieved primarily through one Program Activity: "Biodiversity – Wildlife and Habitat." In support of this, Environment Canada has established a goal specific to ecosystem sustainability, which is "to develop and implement innovative strategies, programs, and partnerships to ensure that Canada's natural capital is sustained for present and future generations."

Environment Canada's activities are directed towards:

- working with communities and stakeholders to complete NWT-PAS planning activities leading towards the establishment of the national wildlife areas; and

- managing six national wildlife areas, including monitoring and collecting inventory of natural resources, managing species at risk, management planning, resource conservation, conducting outreach education programs, regulatory enforcement, and area administration.

A federal cabinet decision is required to create a national wildlife area. Formal designation of the areas as a National Wildlife Area requires an amendment to regulations made under the Canada Wildlife Act. As part of this process, consultations are conducted with local Aboriginal organizations (community and regional level) and other stakeholders; required documentation for this process include a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement, communication plan, legal description of the land, as well as supporting briefing material. Final Proposal, Draft Management Plan, Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement and strategic environmental assessment are forwarded to the Environment Canada Minister and the federal Cabinet for consideration;Footnote 3 it is the prerogative of cabinet to decide if and when a national wildlife area is created. This legislative process for establishing a national wildlife area also includes publication in the Canada Gazette and listing in Schedule I of the Wildlife Area Regulations.

Parks Canada Agency

Parks Canada Agency legislation provides for the creation of national parks under the Canada National Parks Act, national historic sites under the Historic Sites and Monuments Act, and national marine conservation areas under the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act. Under the Conservation Interests initiative, Parks Canada Agency received funding to assess the feasibility of the Thaidene Nene (the East Arm of Great Slave Lake) National Park proposal and to develop and operate the Saoyú-?ehdacho National Historic Site.Footnote 4 It also used agency funding to achieve the protection of the Nááts'ihch'oh National Park Reserve to conserve the upper reaches of the South Nahanni River – this was a site first identified under the NWT-PAS.

Consistent with its normal business practices, Parks Canada Agency generally, works separately from AANDC and Environment Canada to complete all activities involved with these two candidate areas. However, they collaborate on mineral assessments, land withdrawals and land claims negotiations. Assessment and establishment of the Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve involves a feasibility study, community consultation, and communications and promotional products. Funding through this authority seeks only to assess the feasibility of the Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve proposal. Development and operation of the Saoyú-?ehdacho National Historic Site, has completed seven of the eight PAS steps, including land transfer. Funding for this National Historic Site involves setting up and funding a visitor centre, maintaining the national historic site and providing financial support to the Deline First Nation for co-management of the area.

With respect to approvals as it pertains to Parks Canada Agency, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada makes recommendations to the Minister of the Environment regarding the commemoration of national historic sites.

Government of the Northwest Territories

Working closely with AANDC, the Government of Northwest Territories (through the Departments of Environmental and Natural Resources and Industry, Tourism and Investment) provides support to the NWT-PAS Secretariat, which, in turn, provides support to communities and regional organizations for the completion of NWT-PAS 8-steps (for the protection of land under territorial legislation (Territorial Parks Act and Wildlife Act).

1.2.3 Logic Model

A logic model is part of the Initiative's Results-Based Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework. This Results-based Management and Accountability Framework/Risk-based Audit Framework specify expected activities, outputs, and immediate, intermediate and final outcomes. The expected outcomes for the Initiative, which are presented in Annex C include: stakeholder and community support for candidate protected areas and interim protection (immediate); designation of ecologically important sites and permanent protection (intermediate); and, protection of culturally and ecologically important sites without the compromise of resource development (long term).

1.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

1.3.1 Program Management

The NWT-PAS involves collaboration among communities, regional Aboriginal organizations, governments, environmental groups and industry groups. It is led by a multi-stakeholder Steering Committee, which guides and facilitates the implementation process, with the objective of providing a forum for information exchange and offering strategic direction to the territorial and federal ministers on the implementation of the NWT-PAS, including the Mackenzie Valley Five-Year Action Plan. As a community-based initiative, community and regional-level stakeholders play an important role throughout the process, including site identification, preparing proposals for potential sponsoring agencies, and participating on Candidate Area Working Groups and on management bodies for established areas.

The NWT-PAS has a Managing Director who reports to, and receives direction from, the Steering Committee for Strategy Implementation, with the support of the multi-partner NWT-PAS team. The Steering Committee and the Managing Director have access to secretariat support provided by the Government of Northwest Territories and AANDC.

Program / PAS staff and representatives

- Government of Northwest Territories (Industry Tourism and Investment; Environment and Natural Resources)

- Federal government: AANDC/Environment Canada (regions and Headquarters)

- PAS Secretariat staff / Community coordinators

- PAS Managing Director

NWT-PAS Steering Committee

The Steering Committee is composed of 14 organizations that guide the implementation of the NWT-PAS. It provides strategic advice to territorial and federal ministers on the best way to develop a network of protected areas across the NWT. Steering Committee members include:

Eight Aboriginal Groups and Governments

- Akaitcho Territory Government

- Dehcho First Nations

- Gwich'in Tribal Council

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

- North Slave Métis Alliance

- Northwest Territory Métis Nation

- Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated

- Thicho Government

Two Industry Groups

- Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers

- NWT and Nunavut Chamber of Mines

Two Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations

- Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society NWT Chapter

- Ducks Unlimited Canada

The Federal and Territorial Governments

- Government of Canada (AANDC and Environment Canada)

- Government of the NWT

NWT-PAS Secretariat

Staff in AANDC (Headquarters and NWT region) are responsible for the coordination of the NWT-PAS, and work closely with their Government of Northwest Territories counterparts and have formed a PAS Secretariat. The Secretariat is responsible for coordinating and encouraging cooperation among communities, regional organizations, land claim bodies, stakeholders and government institutions; it is also responsible for monitoring and reporting on progress related to commitments made in the PAS and the Mackenzie Valley Five-Year Action Plan.

Managing Director

The NWT-PAS has a Managing Director who supports the Secretariat by overseeing implementation of the NWT-PAS and the Mackenzie Valley Five-Year Action Plan, including coordination and planning of activities, preparation of an annual implementation plan, and monitoring and reporting on progress. This is done in close consultation with members of the Secretariat and approvals are sought from the NWT-PAS Steering Committee. The Managing Director is accountable to the Steering Committee.

1.3.2 Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

Federal government departments and agencies, other levels of government and other non-federal entities, public or private, organizations, individuals, have an interest in the NWT-PAS. These include:

- Federal departments (AANDC, Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency)

- The Government of Northwest Territories

- Aboriginal groups/communities

- Industry

- Environmental non-government organizations

Stakeholders (directly participating in NWT-PAS or involved in protection of land)

- Selected northern communities represented on case study candidate area working groupsFootnote 5

- Mackenzie Valley land protection organizations (e.g. the Mackenzie Valley Environmental Impact Review Board; Mackenzie Valley Land and Water Board)

- Sahtu and Gwich'in Land Use Planning Boards

- Regional organizations

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

- Gwich'in Tribal Council

- Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated

- Dehcho First Nations

- Tlicho Government

- Akaitcho Territory Government

- Northwest Territory Métis Nation

- North Slave Métis Alliance

- Industry representatives on the NWT-PASSteering Committee or candidate area working groups

- Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers

- NWT Chamber of Mines

- The Association of Mackenzie Mountain Outfitters

- Brabant Lodge

- Deghanni Lake Lodge

- Enodah Wilderness Travel

- Hay River Hunters and Trappers Association

- Northern Transportation Company Ltd.

- Norwal Northern Adventures

- Rabesca's ResourcesTamerlane Ventures

- True North Safaris

- Environmental non-government organizations representatives on NWT-PASSteering Committee or candidate area working groups

- Ducks Unlimited

- World Wildlife Fund

- Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society: NWT Chapter

- The Nature Conservancy of Canada

- Other sponsor organizations

Beneficiaries

The implementation of the NWT-PAS supports a balance of land conservation and resource development, which, when complete, is expected to benefit several groups in the NWT and beyond. For instance, protection of traditional sites and wildlife habitat will help to preserve First Nations culture. The ecological benefits of protected areas are also expected to ensure that the areas have the ability to continue providing food, fresh water and other ecological goods and services to First Nations and Northerners. Also, greater clarity around areas set aside for resource development is expected to benefit resource-based industries. Greater resource development, in turn, will benefit First Nations through royalties and Northerners in general through employment and economic development. More generally, protection of a variety of Canadian eco-regions benefits all Canadians.

1.4 Program Resources

Contributions for promoting the safe use, development, conservation and protection of the North's natural resources (Funding Authority 334), is the funding authority that supported the implementation of AANDC's contribution to the NWT-PAS:

To deliver the commitments made in the Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories, AANDC, Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency accessed $25 million from fiscal years 2008-09 to 2012-13. The expected program expenditures for each of the three departments is $8.4 million, over five years, (approximately $1.7/yr). Table 1 below shows the funding is somewhat evenly distributed over the five-year funding period (the period covered by the evaluation). Note that Environment Canada will receive considerably more ongoing funding in order to fulfill its ongoing wildlife area administration, monitoring, outreach and other activities.

| Cash - $000 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 5-Year Total |

Ongoing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment Canada | 1,310 | 1,370 | 2,230 | 1,830 | 1,780 | 8,520 | 2,900 |

| Indian and Northern Affairs | 1,130 | 1,982 | 2,150 | 1,950 | 1,210 | 8,422 | 350 |

| Parks Canada Agency | 1,894 | 2,056 | 1,905 | 1,189 | 1,014 | 8,058 | 750 |

| Total | 4,334 | 5,408 | 6,285 | 4,969 | 4,004 | 25,000 | 4,000 |

The following table shows a breakdown of the expected expenditures of the three federal NWT-partners over the five-year period of funding.

| AANDC | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 5-Year Total |

Ongoing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Salary (incl. Operations and Maintenance | 898,934 | 1,682,849 | 1,850,849 | 1,633,349 | 964,849 | 7,030,830 | 305,630 |

| Total Grants and Contributions | 187,500 | 232,500 | 232,500 | 250,000 | 178,500 | 1,081,000 | 15,000 |

| Public Works and Government Services (Public Works and Government Services) Accommodation | 43,566 | 66,651 | 66,651 | 66,651 | 66,651 | 310,170 | 29,370 |

| Grand Total AANDC | 1,130,000 | 1,982,000 | 2,150,000 | 1,950,000 | 1,210,000 | 8,422,000 | 350,000 |

| Environment Canada | |||||||

| Total Salary (incl. Operations and Maintenance) | 1,196,062 | 1,240,858 | 2,121,246 | 1,722,932 | 1,673,141 | 7,954,271 | 2,740,380 |

| Total Capital Expenditures | 45,000 | 60,000 | 105,000 | ||||

| Public Works and Government Services Accommodation | 68,908 | 69,142 | 108,754 | 107,068 | 106,857 | 460,729 | 159,62 |

| Grand Total Environment Canada | 1,310,000 | 1,370,000 | 2,230,000 | 1,830,000 | 1,780,000 | 8,520,000 | 2,900,000 |

| Parks Canada Agency | |||||||

| Total Salary (incl. Operations and Maintenance) | 1,340,610 | 1,443,860 | 1,634,110 | 831,500 | 806,500 | 6,056,580 | 696,786 |

| Total Capital Expenditures | 390,000 | 398,750 | 107,500 | 357,500 | 207,500 | 1,461,250 | 53,214 |

| Total Grants and Contributions | 150,000 | 200,000 | 150,000 | 500,000 | |||

| Public Works and Government Services Accommodation | 13,390 | 13,390 | 13,390 | 40,170 | |||

| Grand Total Parks Canada Agency | 1,894,000 | 2,056,000 | 1,905,000 | 1,189,000 | 1,014,000 | 8,058,000 | 750,000 |

| Total new funding (all departments) | 4,334,000 | 5,408,000 | 6,285,000 | 4,969,000 | 4,004,000 | 25,000,000 | 4,000,000 |

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation scope covered fiscal years 2008-09 to 2011-12 and focused on the federal government's activities, roles, responsibilities and achievement of results related to this Initiative. It has an overall funding of $25 million over five years (AANDC is allocated $8.4 million over this five-year period). The evaluation also took into account the horizontal, multi-department/agency nature of this Initiative. The evaluation was careful not to evaluate territorial park creation and wildlife activities currently being completed under the wider PAS. The Terms of Reference was approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) in November 2011 and field work was conducted in October 2012.

2.1.1 Objectives of the Evaluation

The main objective of this evaluation was to assess the performance and relevance of the Strategy in accordance with the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The NWT-PAS evaluation addressed the following core evaluation issues:

Relevance:

Issue 1: Continued need for the program;

Issue 2: Alignment with government priorities; and

Issue 3: Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities.

Performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy):

Issue 4: Achievement of expected outcomes (effectiveness); and

Issue 5: Demonstration of efficiency and economy.

The evaluation also looked at design and delivery and alternatives, lessons learned and best practices. Design and delivery focused on the extent to which the program's design contributed to the achievement of the intended results/outcomes.

Evaluation Questions

A suite of evaluation questions along with associated indicators and data sources was developed (see Evaluation Matrix in Annex B). Supplementary evaluation questions were also developed. The evaluation rigorously applied the ten evaluation questions contained in the evaluation framework, which together examined all five core evaluation issues noted above.

Phase 1 - Pre-assessment

The evaluation approach and methodology were informed by the results of an evaluation pre-assessment, which included data and availability assessment, as well as undertaking consultations with federal department/agency stakeholders. Subsequently, a methodology report was prepared, which set out broad directions (e.g. roles and responsibilities of the participating departments) for the second phase of the evaluation (the actual undertaking of the evaluation study).

Collaborative approach

The pre-assessment showed that the Initiative involved AANDC, Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency but only AANDC and Environment Canada relied on the NWT-PAS Steering Committee and Secretariat for the coordination and reporting. Parks Canada Agency's role in the delivery/implementation of the Initiative is significantly different as it uses its own processes (which pre-date the evaluation), thus, its participation in the evaluation was more limited. As a result, a horizontal evaluation involving Environment Canada was deemed the most effective approach, with EPMRB serving as the lead for the evaluation. Parks Canada Agency was kept apprised of all developments and opportunities for exchange of information among the departments were welcomed.

Performance Measurement

The Advancing Conservation Interests in the Northwest Territories Initiative has a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework for establishing Federal Protected Areas in the NWT. This was developed in May 2008.

Phase 2 – Evaluation Study

Following Phase I, the evaluation team refined its work plan to reflect the results of the pre-assessment. The evaluators undertook the following work:

- Developed a detailed questionnaire and, where appropriate (e.g. case studies), involved members of the evaluation working group; these were forwarded to interview subjects in advance with a covering letter from EPMRB requesting their agreement to be interviewed.

- Scheduled and conducted interviews with representatives from AANDC, Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency by phone or in person in the official language preferred by the interviewee.

- Analyzed information gathered from Phase I; Phase 2 included stating the significance of findings, conclusions and making recommendations related to the evaluation issues.

- Prepared a draft evaluation report and shared with Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency (evaluation branches) and AANDC and Environment Canada program representatives for comments.

- Reviewed draft report taking into account comments received from Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency (evaluation branches) and AANDC program representatives.

- Peer review of the draft final report undertaken by EPMRB evaluators.

- Prepared a final report.

Evaluation - Data Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following multiple lines of evidence:

Literature review

The purpose of the literature review was to explore key issues related to the Strategy's relevance and performance, lessons learned, best practices and alternatives. A total of 28 secondary sources were reviewed, including but not limited to, academic articles and papers, government reports and publications.

Program representatives identified and provided documents for review by the evaluation team and suggested documentation from international sources that could contribute to relevant background information. The review of national and international literature helped to inform best practices and assess the economy and efficiency issue. Information was extracted systematically from the literature, using a review template developed by the EPMRB evaluators.

Document and file reviews

The objective of this data collection was to develop a sound understanding of the NWT-PAS in order to be able to address other issues (e.g. success, design and delivery aspects of the program). EPMRB evaluators, with Goss Gilroy Inc., identified and reviewed relevant files and documents during the pre-assessment phase and supplemented these during the data collection phase. Key NWT-PAS documentation that was reviewed included the NWT-PAS achievement reports, proposals, committee reports, frameworks, guidelines, annual reports, Steering Committee Terms of Reference, and strategic plans. A total of 27 document and files were reviewed. The analysis of these documents looked at NWT-PAS products and publications, partners involved, conferences and presentations facilitated by the NWT-PAS, etc.

The documents and files reviewed provided background for the evaluators prior to the field work and helped inform findings and recommendations. Information was extracted systematically from each document and file, using a document review template developed by the EPMRB evaluators.

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews helped researchers gain a better understanding of the perceptions and opinions of individuals who have had a significant role in, or experience with, the NWT-PAS Initiative. Interviews were principally conducted by EPMRB evaluators, although EPMRB evaluators assisted with Environment Canada program staff and management interviews which were conducted by staff from the Environment Canada Evaluation Division. The initial list of key informants totaled 45; 29 were available for interviews (conducted between July and November 2012).

In-person interviews were conducted except where key informants were not available in person; in such cases, telephone interviews were undertaken. Interview questionnaires were e-mailed or faxed to key informants in advance of the interview. Where initial attempts to contact key informants were unsuccessful, up to 10 subsequent attempts were made via phone, email, and fax to schedule potential respondents for an interview. Key informants included the following representatives:

- AANDC (n=6)

- Environment Canada (n=6)

- Parks Canada Agency (n=2)

- Government of Northwest Territories (n=7)

- The NWT-PAS Steering Committee (n=6)

- Environmental Non-government Organizations (n=2)

*The above list does not include First Nations representatives (n=11) who were interviewed as part of the case studies (see below); also, industry representatives (n=2), were interviewed as representatives of the NWT-PAS Steering Committee.

Analysis

Following interviews, data were stored in individual Microsoft Word files. Where appropriate, the repetition of a theme was quantified. Information was captured in a systematic manner according to the evaluation matrix and the generated themes were shared among the evaluators. This was done to ensure accuracy among the interviewers with respect to information collected.

Case Studies

The purpose of the case studies was to provide first-hand external input into evaluation questions. The results from the case studies assisted in interpreting and validating findings, and to provide an external perspective to the evaluation report. AANDC evaluators visited one of the NWT-PAS related communities from October 22-26, 2012, with an additional case study interview completed by teleconference on October 29, 2012. A case study visit protocol was used to guide data collection at these Aboriginal communities. Two AANDC evaluators undertook the community visit.

Selection of the case studies was based on criteria such as: geographic coverage, budgetary considerations and the beneficiaries associated with the projects. Goss Gilroy Inc. and EPMRB developed a case study background profile based on project files (annual reports, proposals) and additional website information. EPMRB (with input from regional AANDC officials) later developed the case study questions. Preliminary findings on the design, implementation, results, impacts, lessons learned and challenges were extracted from those project files. Findings from interviews conducted during the site visits informed the project background descriptions and all evaluation issues. Two case studies with a total of 11 interviewee participants were conducted.

Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

Strengths

- Multiple lines of evidence

The use of multiple lines of evidence helped compensate for any weakness affecting a particular line of evidence; for example, where interviewees declined or did not show up. - Coordination of the evaluation with Parks Canada Agency

As much as possible, some data collection for this evaluation was done in parallel with Parks Canada Agency's Evaluation of Parks Canada's National Park Establishment and Expansion, to be tabled at the Parks Canada Agency evaluation committee meeting in early 2013. The Parks Canada Agency evaluation includes a case study of the Thaidene Nene proposal. While these remained two separate evaluations, such coordination helped in information sharing and cost saving between the two studies.

Limitations

- Key informant interviewees' availability

From a total of 45 potential key informants, half either declined or did not respond to the invitation to participate.

Mitigation: Followed up with potential interviewees and conducted some of the interviews by telephone. However, there was little time for interviewers to probe for more in-depth responses and also prevented interviewers from noticing non-verbal cues. The study followed up with individuals for clarification and also, relied on triangulation of data.

2.3 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

To ensure the quality of its evaluations (e.g. produce reliable, useful and defendable evaluation products), EPMRB uses a mix of quality control tools such as working groups and peer review.

Evaluation Working Group

An evaluation working group, including Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency and AANDC program area representatives was formed in order to provide knowledge and expertise of the NWT-PAS. The working group's mandate was to provide ongoing advice to the evaluation team (e.g. methodology report, proposing key data sources and stakeholders, commenting on evaluation findings, etc).

Internal Peer Review

EPMRB evaluators who are not directly involved in the evaluation project conducted internal peer reviews (e.g. examined the degree to which final reports correspond with the evaluation's Terms of Reference and methodology reports). The reviewers' work is guided by the EPMRB's Peer Review Guides. These guides include questions, which reflect Treasury Board standards for evaluation quality and guidelines for final reports.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

The evaluation examined the continuing need for the NWT-PAS and the extent to which it aligns with current AANDC and federal government priorities, as well as federal roles and responsibilities.

The evaluation concluded that there is a clear and continued need for the NWT-PAS, specifically for a network of protected areas in the NWT. The Strategy is aligned with current Government of Canada and AANDC and Environment Canada priorities and strategic objectives, including Canada's Northern Strategy. The Initiative is also consistent with AANDC's responsibilities under the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, which fosters knowledge of Canada's North, as well as its developmental activities. Moreover, the federal government's role in the NWT-PAS is appropriate and is closely in line with its priorities and strategic objectives, adhering to national and international commitments. Further, the NWT-PAS activities are complementary to the NWT's regional land use planning and do not duplicate other similar activities in the NWT or provided by the Government of Northwest Territories.

3.1 Continued Need

3.1.1 Is there a need for a network of protected areas in the Northwest Territories?

Finding: There is a need for a network of protected wildlife areas and parkland in the NWT. This is largely attributed to: (a) increased interest and activity in economic/resource development in the NWT and its subsequent impact on First Nations, wildlife and habitat; and (b) its complimentarily to regional land use planning.

Home to some of the richest and most diversified resource bases in Canada, the NWT, in recent years, has sparked increasing interest in economic activity and in resource development, particularly in mining, energy, oil and gas. For example, annual expenditures in oil and gas exploration alone have more than doubled, from $130 million in 1999 to $325 million 2008, while capital expenditures invested in mining and oil and gas extraction have also tripled during the same period, from $264 million to $789 million.Footnote 6 The proposed construction of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, stretching from Inuvik to the northwest border of Alberta forecasts potential revenue of $2.2 billion per annum,Footnote 7 but poses significant environmental threats.Footnote 8 At the same time, the NWT is also home to unique ecosystems, flora and fauna, and harbours many species-at-risk, including the Peary Caribou, Whooping Crane, Polar Bear and Wolverine, all highly sensitive to environmental changes.Footnote 9

Key informant interviews, case studies, document and literature reviews indicate that mounting developmental activities and pressures have not only posed a real threat to the future sustainability of the NWT's biodiversity, but also to the preservation of First Nations' culture, tradition and history. For example, case study participants raised the issue of human-modified landscapes, the decrease of animal populations and its impact on the environment and Aboriginal culture, while document and literature reviews indicate rampant land fragmentationFootnote 10 and its adverse effects on plant and animal habitat. One of the expectations of the NWT-PAS is to preserve Aboriginal culture, tradition, history and the environment, while benefiting communities, all Canadians and future generations. For instance, it is anticipated that permanent protection in Saoyú-?ehdacho will result in "positive and important impacts from the protection of cultural, traditional and educational resources for the Sahtugot'ine."Footnote 11 This includes the preservation and transference of traditional knowledgeFootnote 12 and the preservation of "a rare cultural landscape for all time."Footnote 13

The greatest concerns raised by First Nation interview and case study participants were the ongoing and projected growth in economic/resource development in the NWT and the adverse impact it would have on Aboriginal lifestyles, including vitally important social, cultural and economic activities that many continue to practice (i.e., hunting, gathering and medicinal practices). Case study participants indicated that their communities have already observed much of these impacts though specific examples were not offered. Considering the overall context of the Strategy, the evaluation finds the need to ensure a measure of environmental protection as well as a sustainable ecosystem, particularly since 51 percent of the territorial population is Aboriginal;Footnote 14 otherwise, Aboriginal Peoples are vulnerable to losing their connection to the land.

Duplication

The issue of continued need also raises the matter of duplication. The evaluation found that the NWT-PAS does not duplicate any other protection measures in the NWT. The Strategy is similar only to regional Land Use Planning (LUP) to the extent that they both establish conditions that control the use of land, but diverge in three particular areas:

- Timing of protection – LUP usually offers short-term protection, often for a five-year period after which the protection scenario can be reviewed and possibly renewed; a protected area designation can offer long-term protection.

- Type of protection – LUP offers more flexible protection; National Wildlife Areas, National Parks and Historic Sites offer secure protection that is less flexible. Under the laws used for long-term protection, it is hard to change things like boundaries or the type of activities allowed.

- Complimentary relationship between NWT-PAS and LUP – NWT-PAS identifies and gathers a wide range of information about special areas of land anticipated for protection. The LUP uses the information from the NWT-PAS process to move an area of land through its process and vice versa.

Of note, whereas a regional LUP can be required for regions/areas, if specified in an established land claim, the NWT-PAS provides communities without a comprehensive land claim the opportunity to also set objectives for conservation and resource management. This difference was especially noted by case study participants; communities without a comprehensive land claim would otherwise not have any available tools for desired conservation efforts. Thus, the evaluation found that the NWT-PAS fills an important gap that regional LUPs leaves behind, which is establish protected areas in unsettled land claims. In settlement areas, the NWT-PAS and LUP are complementary processes.

All lines of evidence argue that there is a need for: sustainable economic development; a network of protected wildlife areas and parkland in the NWT (parkland is discussed in more detail in 3.2.1); the protection of important ecological and cultural sites in the NWT as the Strategy is able to operate in unsettled land claim areas, thus, filling a gap left by regional LUP.

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

3.2.1 Is the NWT-PAS aligned with federal government priorities?

Finding: The Strategy is aligned with Government of Canada priorities and with AANDC, Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency priorities.

Affirming the need for balance between environmental protection and economic development in the NWT, the Auditor General of Canada stated in 2010 that the "federal government has specific obligations relating to the effective governance, environmental protection, and capacity building to provide sustainable and balanced development in the Northwest Territories. Failure to meet these obligations could mean missed economic opportunities, environmental degradation and increased social problems in NWT communities…"Footnote 15 The Government of Canada had previously indicated that sustainable development is a priority, even well before the establishment of the NWT-PAS in 1999, by ratifying numerous international and national commitments. International commitments include the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) and the Inuvik Declaration (1996), while national plans and obligations include Canada's Green Plan (1990), the Tri-Council Statement of Commitment (1992), the Whitehorse Mining Initiative (1994), the Joint Federal-Territorial Task Force on Northern Conservation (1994), the Minerals and Metals Policy (1996), the Federal Water Policy, the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy (1996), and the Mackenzie River Basin Trans-boundary Waters Master Agreement (1997).

Likewise, both federal and NWT governments have committed to sustainable natural resource management and development that include policy commitments calling for increased regulation of industries interested in developing the NWT's natural resources. Such initiatives include the North of 60 Action Plan (2001), the Government of Northwest Territories' Sustainable Development Strategy (1993), Non-renewable Resource Development Strategy (1998), Improving the Northern Operating Environment (2001), and the Environmental Stewardship Framework and the NWT Water Stewardship Strategy (2010). Case studies, interview participants and document and literature reviews also indicate that the NWT-PAS is aligned with the priorities of the three sponsoring bodies: AANDC, Environment Canada and Parks Canada Agency.

In addition, interview and case study participants expressed the significance of federal support in the Initiative, particularly since communities, industry and other third parties would otherwise have very limited capacity to participate in the program. Interview and case study participants indicated that communities would be financially unable to participate in working group and Secretariat meetings, as well as the greater NWT-PAS process since their resources are spread quite thin. Interview participants also expressed concern for the future capacity of environmental non-government organizations in the NWT-PAS without federal support since their capacity had significantly decreased since the recent global financial crisis, specifically citing the consequential withdrawal of the World Wildlife Fund's support in the Initiative.

AANDC and NWT-PAS

The NWT-PAS serves to support the Department's broad mandate in the North. The AANDC Minister is mandated through the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada Act to oversee the resources and affairs of Canada's three territories. The strategic objective is to support the sustainable development of the North's natural resources while also protecting Arctic ecosystems for the use and enjoyment of future generations.

AANDC is responsible for the administration and management of all Crown land in the NWT and is also responsible for granting interim land withdrawals and, as a result, plays a crucial role in the NWT-PAS. Working in conjunction with the Government of Northwest Territories, the Department provides financial resources to communities and helps coordinate efforts to identify, assess and seek sponsors for protected areas. For example, AANDC undertakes non-renewable resource assessments to evaluate the mineral and petroleum potential of candidate protected areas with the aim of realizing future economic development and conservation opportunities.

Environment Canada and NWT-PAS

Environment Canada's strategic outcome that "Canada's natural environment is conserved and restored for present and future generations," as well as the Canadian Wildlife Service's mandateFootnote 16, also indicate alignment with the NWT-PAS. In addition, Environment Canada has commitments to the Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy(2012) and reports to the Convention on Biological Diversity, International Union for the Conservation of Nature's World Commission on Protected Areas, as well as to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development regarding the state of Canada's conservation efforts.

Parks Canada Agency and NWT-PAS

Parks Canada Agency's priorities are also directly related to the NWT-PAS. In particular, its legislation provides for the creation of nationals parks under the Canada National Parks Act and national historic sites under the Historic Sites and Monuments Act. An evaluation undertaken by Parks Canada Agency indicates that the establishment and expansion of national parks is consistent with Parks Canada Agency's mandate and priorities (under the sub-activity National Park Establishment and Expansion of Program Activity 1, Heritage Places Establishment), which continues to be a priority for Parks Canada Agency, as reflected by its corporate plans. Establishing national parks that are representative of Canada's 39 natural regions has been an ongoing commitment since the first National Parks System Plan was released in the early 1970s. Parks Canada Agency's National Parks Policy adds to this commitment, specifically stating that efforts to establish new parks will be concentrated on those natural regions that do not have a national park, such as the Northern Boreal Uplands in the NWT (to be represented by the establishment of the Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve).

In addition, the Parks Canada Agency Act (1998) states that it is "in the national interest to protect the nationally significant examples of Canada's natural and cultural heritage in national parks" and "to include representative examples of Canada's land and marine natural regions in the systems of national parks and national marine conservation areas." Further, the Act indicates a need for a long-term plan for national parks and confirms Parks Canada Agency's role for negotiating and recommending the establishment of new national parks to the Minister.

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

3.3.1 Is the NWT-PAS aligned with federal roles and responsibilities?

Finding: While the NWT-PAS is appropriately aligned with federal roles and responsibilities, it is presently unclear how and to what extent devolution may impact the federal government's roles.

Evidence from key informants, case studies and document and literature reviews suggest that the roles and responsibilities of the federal government are appropriately aligned with the NWT-PAS in light of federal and departmental priorities discussed in 3.2.1., and specifically in terms of contributing to the fulfillment of international environmental commitments and conservation efforts in the NWT.

The Government of Canada subscribes to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the world's largest global environmental network, which has adopted protected area management categories to classify protected areas according to their management objectives. Canada's national parks fall under Category II – National Parks, reporting that "Natural area of land and/or sea, designated to: (a) protect the ecological integrity of one or more ecosystems for present and future generations; (b) exclude exploitation or occupation inimical to the purposes of designation of the area; and (c) provide a foundation for spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities, all of which must be environmentally and culturally compatible." The International Union for the Conservation of Nature 1994 Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories, suggested that ownership and management of these areas should normally be undertaken by the highest competent authority of the nation, while maintaining jurisdiction over such responsibilities. More recently, International Union for the Conservation of Nature guidance (2008) has recognized that national parks may also be vested in another level of government, council of indigenous people, foundation or other legally established body.

Emphasizing the importance of the federal government's role, key informants indicated that significant barriers to land protection without federal sponsoring legislation exist, including financial resources and regulation. In other words, according to key informant interviews,there is limited community and local legislative capacitygoverning the NWT-PAS. Hence, the federal government's legislative responsibility as manager of Crown lands for the long-term benefit of Northerners and all Canadians is important.At the same time, the Strategy compliments other protection measures in the NWT. In particular, the Strategy is an accompaniment to LUPs, which is discussed in more detail in Section 3.1.1. Parks Canada Agency's National Park and/or National Historic Site designations and Environment Canada's Canadian Wildlife Service's Migratory Bird Sanctuaries are compatible with the NWT-PAS.

NWT-PAS and Devolution

The Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada Act establishes AANDC as lead federal department in the North. Through the Northern Affairs Organization, the Department is responsible for two equally important mandates - Indian and Inuit Affairs and Northern Affairs. Northern Affairs Organization's mandate include: meeting the federal government's constitutional, political and legal responsibilities in the North; and administering most northern lands (except those devolved to territorial governments or Self-Governing First Nations). The Northern Affairs Organization's priorities, among other things, involve the Northern Strategy and Devolution. "Devolution" is the transfer of authority from the Government of Canada to the Government of Northwest Territories.

The Government of Canada and the Government of Northwest Territories have been negotiating for years on the issue of devolution. The evaluation has found that at the time of writing this evaluation report (December 2012 – January 2013), there was uncertainty with respect to devolution and its relation and/or impact on the NWT-PAS. Specifically, there are differing perspectives in terms of federal roles and responsibilities and how it will align with the NWT-PAS when devolution of lands and resources comes into effect in the NWT. AANDC reports, "Federal departments that have a wide role in the management of lands and resources such as the national Energy Board, Natural Resources Canada, Environment Canada and Parks Canada may see the way they do this work in the NWT change as a result of devolution."Footnote 17

Key informants maintain two differing positions, that: (a) federal roles and responsibilities will continue to be appropriately aligned with the program, particularly as it could take an unspecified amount of time for the Government of Northwest Territories to create stronger land protection tools for protected areas; while the second (b), questions the role of the Government of Canada in land claims and LUP, noting that the role is ambiguous at present (focusing on economic development while promoting environmental protection) and there is no clear path forward that will address the NWT-PAS process in the event of devolution. However, it must be stated that this latter group of key informants voiced their support in the Government of Canada's role in general conservation efforts to which it made commitments, such as the Canada Wildlife Act, Species at Risk Act and the Migratory Birds Convention Act.

It is expected that the NWT devolution initiative will transfer control over federal Crown (public) lands and resources, including rights in respect of water, from the Government of Canada to the Government of Northwest Territories.Footnote 18 The document review highlights the expectation that as a result of devolution, the Government of Northwest Territories will receive a transfer of "province-like" powers: administration and control over Crown (public) lands, including land/non-renewable resource management, assets, funding and staff, influence over economic/environmental issues and retention of some residual social/economic roles. This will give the Government of Northwest Territories the ability to grant interests as an owner of lands and resources, in the same way the federal government is able to do so presently. Thus, while having increased authority to make decisions about the way public lands, resources and waters are managed, including the way the economy is developed and the way the environment is protected, there will be increased opportunity for the Government of Northwest Territories, Aboriginal governments and NWT residents to work together on land management and natural resource stewardship strategies. According to Government of Northwest Territories documents, "this means that decisions about development and the environment will better reflect northern needs and priorities,"Footnote 19 but initially, the Government of Northwest Territories will mirror existing federal legislation and processes to ensure a smooth transition.