Archived - State of Performance Measurement in Support of Evaluation for 2009-10 and 2010-11

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Final Report

Date : November 2011

PDF Version (194 Kb, 42 Pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| APS |

Aboriginal Peoples Survey |

| DPR |

Departmental Performance Report |

| EIS | Education Information System |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| EPMRC |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee |

| FNCFS-IMS |

First Nations Child and Family Services – Information Management System |

| ICMS |

Integrated Capital Management System |

| IM/IT |

Information Management/Information Technology |

| INAC |

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada |

| MRRS |

Management, Resources and Results Structure |

| PAA |

Program Activity Architecture |

| PM |

Performance Measurement |

| PMF |

Performance Measurement Framework |

| RBAF |

Results-Based Audit Framework |

| RMAF |

Results-Management and Accountability Framework |

| RPP |

Report on Plans and Priorities |

| SPPD |

Strategic Planning Policy and Research Directorate |

| TBS |

Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada |

Executive Summary

Background

The Treasury Board Secretariat Directive on the Evaluation Function requires that departmental heads of evaluation prepare an annual report on the state of performance measurement in support of evaluation. In 2009, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) tabled its first report, which covered activities for 2008-09. The report identified ten attributes of quality performance measurement systems in high performing organizations. These attributes were then employed as benchmarking criteria against which the AANDC performance measurement activities could be examined. These same criteria form the basis of the current report, which covers 2009-2011.

Key Findings

During the two years, AANDC has taken steps to establish the foundation for advancing performance measurement in the Department. As a first step, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) added the development of performance measurement strategies to its annual plan to encourage the collection of information on results to inform future evaluations. The Branch also created a governance process that engaged internal partners in the development of performance measurement strategies and senior management in the approval of strategies.

A performance measurement team was formed and created information sessions and materials to raise awareness of the importance and use of performance data and encourage a shift towards results-based management. Capacity development was also encouraged through the creation of a guide for the development of performance measurement strategies and the provision of advice to program representatives. In addition, they coordinated a special study on thematic indicators to assist with the identification of indicators. Between April 2009 and March 2011, a total of 19 performance measurement strategies were reviewed by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee, which is chaired by the Deputy Minister.

Other sectors have also been working to advance performance measurement. Several program areas, including education, infrastructure, consultation and policy, and child and family services have developed, or are developing, information management systems that will capture performance information. AANDC also has a current and active Information Management Strategy.

The Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), has been a key source of information on a broad array of demographic and socio-economic characteristics of First Nations, Métis, Inuit, men and women, and for all of Canada (on reserve, North, off reserve, urban). AANDC has been working to resolve participation issues for the next generation of the APS.

Four lines of evidence were pursued to assess the impact of activities identified above: A document/literature review, interviews, a focus group, and ranking. The ranking of AANDC's performance in each of the 10 key attributes identified in the Benchmarking Report is as follows:

Text description of The ranking of AANDC's performance

Scale used to rank AANDC's performance

This figure is a depiction of the scale used to rank AANDC's performance in each of the 10 key attributes identified in the Benchmarking Report. From left to right, the rankings on the scale are as follows: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. The following attributes were ranked under "attention required": Community needs, credible performance information, implementation, performance information is used, and culture. The following attributes were ranked under "opportunity for improvement": Leadership, capacity, and communication. The following attributes were ranked under "acceptable": Roles and responsibilities and alignment with strategic direction. No attributes were ranked as "strong."

The findings show the Department has made progress in advancing performance measurement but as shown in the ranking above, also identified some areas for improvement. AANDC lacks a coordinated approach to developing leadership, engaging communities and increasing capacity in support of a results-based culture. In addition, there continues to be a lack of usable performance data (data that can be used to assess whether a program has achieved stated objectives). Data collected, data needs, data use, and linkages of Performance Measurement (PM) data to departmental strategic outcomes are not well understood. In short, the development of a results-based culture is in its infancy at AANDC.

To address the weaknesses above, the "Assessment" sections of the analysis of the ten key attributes suggest horizontal engagement at all levels to:

- Improve leadership and develop capacity to advance results-based management and PM in the Department.

- Improve and advance partnerships and collaboration, including how we might engage communities and simultaneously help to address the reporting burden.

- Better understand what data is currently collected and identify data needed to better understand and report on impacts and results.

- Monitor the implementation of PM strategies and the use of PM data.

- Promote the growth of a PM culture at AANDC.

Conclusion and Next Steps

To address the issues above and promote the growth of a performance-focussed culture at AANDC, EPMRB is committed to:

- Wider engagement at all levels to improve leadership, identify incentives to using performance information, and enhance capacity.

- Promoting enhanced collaboration with internal and external partners to ensure that better information is available to support effective performance measurement and management for results.

- Developing a communications plan, which targets different audiences to encourage the acceptance of performance measurement as an essential tool for management.

- Analysing data currently collected, data needs for performance reporting and reducing reporting burden.

- Introduce a follow-up strategy on the implementation of PM strategies. This strategy will contribute to the assessment of the state of performance measurement at AANDC and will provide an exchange forum for programs and partners allowing identification of barriers, best practices, needs for communication, and training products.

1. Introduction

In April 2009, the Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada (TBS) established the Policy on EvaluationFootnote 1, whichhas significant impact on how evaluation is approached in federal departments and agencies. With a focus on decision making and accountability, the Policy emphasizes the importance of collecting credible, timely and neutral information to report on the relevance and performance of government programs and services. It has led to enhanced expectations around evaluation coverage and the quality of evaluation projects, as well as the implementation of ongoing performance measurement (PM) to support this work.

The TBS Directive on the Evaluation FunctionFootnote 2 outlines roles and responsibilities for deputy ministers, program managers and heads of evaluation. Specifically, in relation to PM, the Directive indicates that heads of evaluation are responsible for reviewing and providing advice on PM strategies, as well as providing guidance on accountability and performance provisions detailed in Cabinet documents. They are also responsible for reviewing and providing advice on the Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) embedded in their department's Management, Resources and Results Structure (MRRS). Lastly, they are responsible for submitting an annual report to their departmental evaluation committee on the state of PM in support of evaluation.

In 2009, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) formerly Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) tabled its first report on the state of performance measurement, entitled "State of Performance Measurement of Programs in Support of Evaluation at Indian and Northern Affairs Canada"Footnote 3. This first report (hereafter referred to as the Benchmarking Report) covered 2008-09 and was approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) in September 2009. The preparation of the second report was delayed to allow for work on PM strategies, and, the report was delayed further by heavy workloads and contracting issues. As a result, this report covers both 2009-10 and 2010-11.

It is important to note at this juncture that AANDC recognises that PM serves more than the evaluation function. Performance information can be used for policy development, planning, monitoring, decision making and reporting, and also responds to a government-wide shift toward results-based management and culture. Further, while the Deputy Minister, program managers and the Head of Evaluation (Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive) have been guided by, and have responsibilities flowing from, TBS policies and directives, it is clear that all areas of AANDC have a role to play in ensuring access to relevant, reliable data and data management systems and performance reporting. This report analyses actions taken throughout the Department.

1.1 Context

The Benchmarking Report introduced a broad frame of reference in interpreting and assessing the performance measurement work throughout the Department, including the identification of key partners and stakeholders. To guide the assessment, research was conducted to identify the main attributes of quality performance measurement systems characteristic of high performing organizations. These attributes were then employed as benchmarking criteria against which the Department's PM activities could be examined.

In total, ten criteria were established to guide the assessment. Table 1 provides a high level account of these attributes. Overall, the Benchmarking Report indicated that AANDC had made considerable progress in developing an effective PM system primarily through leadership and capacity building initiatives. Key areas for improvement included enhancing communication and stakeholder engagement, and clarifying roles and responsibilities associated with PM activities.

Table 1: The Ten Key Attributes of a Quality Performance Measurement System

| KEY ATTRIBUTE | BRIEF DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Leadership | Senior levels of an organization are involved/seen as involved and actively support a performance measurement culture |

| Clear Accountability | Performance measurement roles and responsibilities are well articulated and understood at all levels in the Department |

| Community Needs | Needs and capacity of the community being served by PM activities are integrated into the process |

| Alignment with Strategic Direction | Performance measurement is aligned with strategic direction of the Department |

| Performance information is credible | There is confidence in the information and data captured through PM activities |

| Implementation | PM activities are fully implemented and monitored |

| Capacity | Stakeholders have the capacity to fulfill the requirements for performance measurement. |

| Performance Information is used | Performance measurement information and data are used to inform decision making, planning and reporting |

| Communication | All stakeholders and partners are engaged and staff are aware of the value of PM activities and their role |

| Culture | There is a well established culture that focuses on results, where PM activities effectively support the operation environment of the Department |

Please note that some names and definitions for attributes have been refined for this report. For example, "Clear Accountability" above is defined above as the articulation of roles and responsibilities. The name for this attribute was changed in this report to "Roles and Responsibilities" to better reflect the definition.

1.2 Rationale & Scope

The title of this report suggests the intended purpose is to discuss performance measurement in support of evaluation, but the scope of the report is much larger. Recognising that performance measurement contributes to results-based management as well as to evaluation, the report explores the contribution of performance measurement to program management, monitoring and reporting as well as to evaluation. Indeed, it will be difficult to measure the impact of PM on evaluation until evaluations are conducted on programs with fully-implemented PM strategies, which will not occur for another three to four years. In the short term, attention will focus on broader PM building efforts as per current TBS direction. Future versions of the annual report on the state of performance measurement can explore the impact of PM on evaluation as PM strategies are implemented and the associated programs are evaluated.

For the purposes of this report, PM activities refer to those activities undertaken to support monitoring, measuring, evaluating and reporting on the performance of AANDC programs and services. An emphasis was placed on examining activities related to the development and implementation of performance measurement strategies, given their key role in supporting the Department as it responds to commitments under the Policy on Evaluation and the associated Directive.

1.3 Data Collection and Methodology

In November 2010, the Terms of Reference for this project were approved by the EPMRC. Research activities commenced in December 2010 and were concluded in March 2011. In addition to meeting TBS requirements, this report will help to advance AANDC's performance measurement agenda by identifying lessons learned, best practices and opportunities for moving forward.

Multiple lines of evidence were used to inform the findings of this report. The following sub-sections provide accounts of the key data sources and the methodologies applied.

1.3.1 Document and Literature Review

For information on the environment surrounding performance measurement across government, federal government reports and plans were examined. In addition, during the months of January and February 2011, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) also collected AANDC Audit and Evaluation reports, as well as performance measurement strategies, approved since April 2009. Relevant corporate reports, policies and plans, as well as documents available on special initiatives and studies, were also examined. Together, these documents were reviewed for details on the nature of PM activities taking place across the Department's program sectors and corporate divisions, including strengths, areas of progress, challenges and opportunities for improvement. Lastly, published and non-published literature were collected to provide reference material associated with the 10 key attributes, including best practices and lessons learned.

Interviews

Face-to-face interviews were conducted in February and March 2011 with a sample of AANDC senior management at the director or directors general level. The goal of the interviews was to learn more about the PM activities taking place across departmental sectors, to gain insights on some of the Department's key successes and challenges, and to identify any efficiency gains or areas for improvement. Participants were chosen using an informal sampling strategy. The Department's organizational chart provided a reference list and, the sampling frame was defined as senior management representatives of the key program sectors. From this simplified list, individuals invited for an interview were drawn from those believed to have the most knowledge on the PM activities underway in their respective sectors, as well as across the Department more generally. Given the relevance of their business to the subject of this report, senior management from the Audit and Evaluation Sector, and the Deputy Minister's Special Representative on Reduced Reporting, were also added to the list of invitees. Overall, 13 of the 15 executives invited to an interview agreed to participate, representing a response rate of 81 percent. A copy of the interview guide is provided in Annex A of this report.

1.3.3 Focus Group

The purpose of the focus group session was to obtain feedback and insights pertaining to the development and implementation of PM strategies. Representatives of programs that had engaged in the development of a PM strategy between April 1, 2009, and March 31, 2011, were invited to attend the session held in March 2011. In total, 27 program representatives were invited to attend the session, with eight agreeing to participate. Discussion questions used during the session were also circulated after the focus group session via e-mail to encourage those unable to attend to submit written feedback. Additional responses were received from three more program representatives, raising the overall response rate to 41 percent. A copy of the focus group discussion guide is provided in Annex B of this report.

1.3.4 Ranking

New to this version of the State of Performance Measurement report is a ranking of the Department's performance in each of the 10 key attributes identified in the Benchmarking Report. The levels of measurement used are the same as those used for the Management Accountability Framework:

(Levels of measurement: attention required; opportunity for improvement; acceptable; strong)

In order to guide the ranking, the key attributes were further defined and indicators were developed. The rankings were assigned using the information collected through the document and literature review, interviews and focus groups.

1.4 Project Limitations

A number of challenges were encountered in the preparation of this report. For example, it was difficult to retrieve data corresponding to all PM activities across sectors because no formal network exists to share information on PM in the Department. As a result, much of the documentation reviewed was prepared within the Audit and Evaluation Sector. This limitation will be partially addressed by sharing a draft report with, and collecting comments from, key partners and the Director General Policy Coordination Committee.

Similarly, while some effort was made to capture activities throughout the Department, many of the actions presented and the proposed next steps are largely focused on EPMRB. Since performance measurement requires an organization-wide approach, future reports should better integrate the activities of other sectors.

The process for selecting interviewees may not have resulted in the identification of the strongest candidates. As stated earlier, senior managers believed to have the most knowledge on the PM activities underway in their respective sectors, as well as across the Department more generally, were selected for an interview. Departmental representatives knowledgeable of PM activities may not have been selected for an interview and the perspectives of officer-level staff were not captured.

Focus groups were not well attended. Out of 27 invitees, only eight attended with an additional three responding to discussion questions electronically. Participation in both interviews and focus groups may have been hampered by the timing of these events in the fourth quarter (end of fiscal year).

It was difficult to assess departmental progress in relation to the 10 key criteria as metrics were not established in advance of data collection. Indictors were established to help identify what to look for, but the indicators were identified after data collection was complete. As a result, the ranking drew upon available information, which did not always relate to the indicators. A balance of quantitative and qualitative sources must be established for future reports to reduce reliance on interviews and/or focus groups.

2. Key Findings

In order to provide some background and context for the discussion of findings, the following text provides a description of the evolution of the EPMRB PM team and activities during the 2009-10 and 2010-11 fiscal years. PM activities of other internal groups are also highlighted.

In 2009-10, a small team consisting of a manager and 2.5 staff, was created in EPMRB to respond to performance measurement requirements as stipulated in the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation. The team existed separately from the EPMRB evaluation teams in order to focus on performance measurement. Activities of this team were informed by the first report on the 2009 Benchmarking Report and the 2008 Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF) Special Study, which highlighted issues related to the identification of objectives, performance measures, outcomes, targets, data collection mechanisms, baseline data, monitoring, and reporting. Although the team focused primarily on the development of PM strategies, the five priority areas for the team included: planning, governance, engagement of players, capacity-building, and assessing progress.

Planning was addressed through the integration of PM strategies in 2009-10, into the annual update of the departmental evaluation plan. Requirements for PM strategies were largely based on evaluation recommendations and the 2008 RMAF Special Study, which ranked the strength of existing RMAFs/Results-based Audit Framework (RBAF) reports. Those with a weak rating were given priority. In addition, TBS analysts demanded PM strategies for a number of programs eligible for funding under the New Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development prior to the release of any funds.

In 2009-10, 26 PM strategies were identified in the plan for completion, with seven PM strategies deemed high risk, to be brought forward to the EPMRC for approval. By integrating PM strategies within the Annual Update of the Five-year Evaluation Plan, it was felt that the Department would be in a better position to ensure that performance data is available for ongoing results-based management and for scheduled program evaluations.

Governance refers to the establishment of roles, responsibilities and processes relating to the development of performance measurement in the Department. From April 2009 to March 2011, EPMRB supported the development of PM strategies through capacity-building in the programs by way of presentations and participating in/leading workgroups on logic model development and identification of performance indicators. Indicator development was also aided by the 2009-10 Thematic Indicators Project, which identified key performance indicators across six thematic areas that represent the broad scope of AANDC's mandate: Health and Well-being; Environment; Education; Economy; Governance; and Infrastructure. The report does not propose a set of prescriptive indicators, but rather encourages a shift in thinking about the purpose and spirit of performance measurement as the indicators identified have broad application across program areas in the Department.

Capacity building was also addressed through the creation of the INAC Guidance for Program Managers on PM Strategies, which was approved by the EPMRC in December 2009. This guidance document was aligned with TBS guidance and introduced the concept of performance measurement, outlined roles and responsibilities, described the governance process outlined above, and provided definitions and step by step advice on the preparation of the key components of a PM strategy. The annexes to the report contained a number of templates, assessment tools and more. This guidance document was updated in November 2010 and remains an 'evergreen' reference manual, reflecting best practices retrieved from observations of both the corporate and federal government experience.

From the outset, PM strategies were signed off by program assistant deputy ministers (ADMs), approved by the Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive and submitted to the EPMRC for information purposes only. Only PM strategies deemed "high risk" were brought to the EPMRC for approval. In the November 2010 guidance document, an approval process was introduced whereby program ADMs present their PM strategies to the EPMRC for final approval. The current governance process for the development, approval and implementation of PM strategies is outlined below:

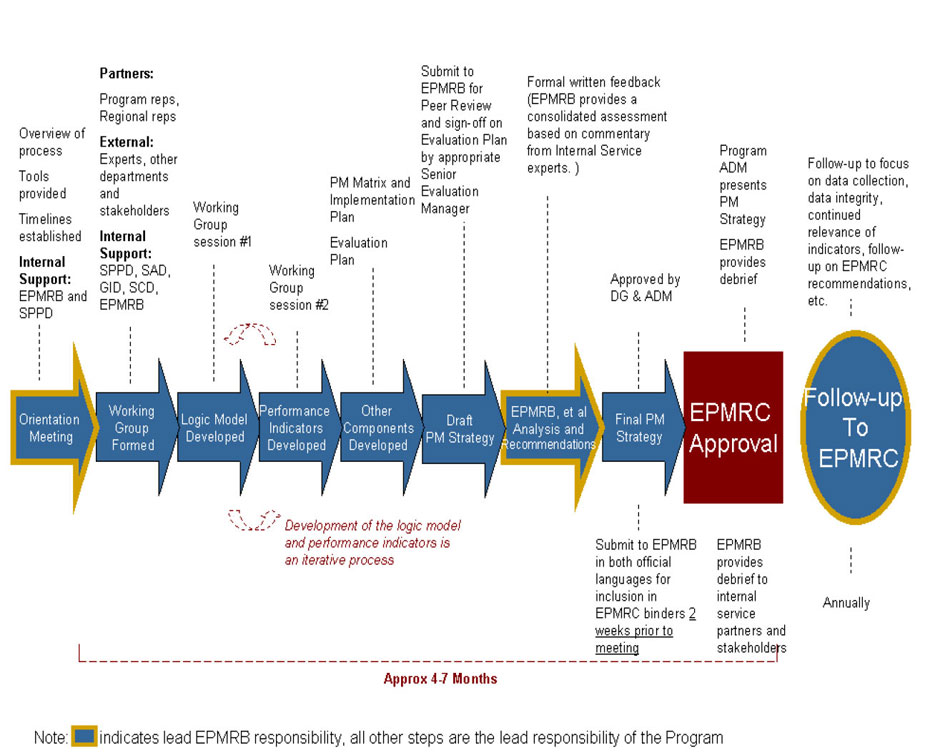

Figure 1: PM Strategy Process Map

Text description of Figure 1

Figure 1: PM Strategy Process Map

This figure is a map of the current governance process for the development, approval, and implementation of PM strategies.

- The first stage in this process is the orientation meeting, which includes an overview of the process, the allocation of tools, and the establishment of timelines. The internal support involved in this stage includes EPMRB and SPPD. This stage is led by EPMRB.

- In the second step, a working group is formed. Partners include program reps and regional reps. External support includes experts, other departments, and stakeholders. Internal support includes SPPD, SAD, GID, SCD, and EPMRB.

- The third step in the process is logic model development. This step involves the first session of the working group.

- The fourth step involves the development of performance indicators, at which point the second working group session is held. The development of the logic model and performance indicators is an iterative process.

- The fifth step in the PM strategy process involves the development of other components, including the Evaluation Plan and the PM Matrix and Implementation Plan.

- The sixth step in the process is drafting the PM strategy. This involves submitting the PM strategy to EPMRB for Peer Review and the signing off on the Evaluation Plan by the appropriate Senior Evaluation Manager.

- The seventh step is EPMRB, et al analysis and recommendations, which involves formal written feedback. EPMRB provides a consolidated assessment based on commentary from Internal Service experts. This step is led by EMPRB.

- In the eighth step, the final PM strategy is submitted to EPMRB in both official languages for inclusion in EPMRC binders 2 weeks prior to the meeting. It is also approved by the DG and the ADM.

- The PM strategy is then taken to EPMRC for approval. The program ADM presents the PM strategy and EPMRC provides a debrief to internal service partners and stakeholders.

- Finally, in the follow up to EPMRC, there is a focus on data collection, data integrity, and continued relevance of indicators. EPMRC recommendations are also followed-up on. This stage of the process occurs annually and is led by EPMRB.

The entire PM strategy process takes approximately 4-7 months.

As noted above, EPMRB also engaged key AANDC internal services partners in the development of PM strategies in order to integrate performance indicators on gender issues, of interest to the Gender Issues Directorate, and sustainable development, which is the responsibility of the Sustainable Communities Directorate. Indicator development was also of interest to the Strategic Priorities and Planning Directorate (SPPD), which is responsible for the PMF, which serves as a departmental inventory of performance measures to be used in the Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP), Departmental Performance Report (DPR), Strategic Plan, Business Plan, Quarterly Reports, and PM strategies. The Strategic Planning and Analysis Branch contributed to the identification of possible data sources and the Information Management Branch had an interest in proposed data collection systems.

EPMRB has hosted sessions with its internal partners to help clarify the roles and responsibilities associated with the Department's PM activities. In November 2010, the EPMRB performance measurement team hosted a Performance Measurement Collaboration Workshop. The workshop's objective was to provide internal partners with an opportunity to identify and discuss their role during the PM strategy development process, and to raise key challenges and opportunities for better coordination. At the conclusion of the workshop, EPMRB established formal partnerships with the following corporate partners: Gender Issues Directorate, Sustainable Communities Directorate, SPPD, Strategic Analysis Directorate, and Information Management/Information Technology (IM/IT). A "swat team" approach was created for reviewing/providing feedback on PM strategies prior to submission to the EPMRC. Partners attend logic model and indicator workshops and provide formal feedback on the draft PM strategies.

The above actions related to planning, governance, engagement of players, and capacity-building contributed to the completion of three PM strategies in 2009-10 and another 16 in 2010-11. A review of the 19 PM strategies against 15 key components of a PM Strategy (such as program description, logic model, and implementation plan), shows a high level of consistency in the content of PM strategies. Figure 2 below shows the findings from this review.

Figure 2: Contents of 19 Performance Measurement Strategies approved in 2009-10 and 2010-11

Text description of Figure 2

Figure 2: Contents of 19 Performance Measurement Strategies approved in 2009-10 and 2010-11

This figure is a graph showing the contents of Performance Measurement Strategy reports approved in 2009-10 and 2010-11. The number of reports is located on the left-hand side of the y-axis and the percentage of total reports is located on the right-hand side of the y-axis. The components of the reports are located on the x-axis. These components include: Program description, logic model, activities, outputs, outcomes, risk assessment, PMS matrix, PMS data sources identified, PMS indicator targets, PMS alignment to PAA, PMS implementation plan, performance measurement data risks, reporting burden, evaluation strategy/matrix/plan, and performance measurement challenges. A Program Description was included in 19 reports, which amounts to 100% of the reports. A Logic Model was included in 19 reports, which amounts to 100% of the reports. A component on Activities was included in 19 reports, which amounts to 100% of the reports. A component on Outputs was included in 19 reports, which amounts to 100% of the reports. A component on Outcomes was included in 19 reports, which amounts to 100% of the reports. A Risk Assessment was included in 17 reports, which amounts to 90% of the total reports. A PMS Matrix was included in 19 reports, which amounts to 100% of the total reports. PMS Data Sources were identified in 16 reports, which amounts to 85% of the total reports. PMS Indicator Targets were included in 16 reports, which amounts to 85% of the total reports. A component on PMS Alignment to PAA was included in 7 reports, which amounts to 37% of the total reports. A PMS Implementation Plan was included in 18 reports, which amounts to 95% of the total reports. Performance Measurement Data Risks were included in 11 reports, which amounts to 58% of the total reports. A Reporting Burden component was included in 3 reports, which amounts to 16% of the total reports. An Evaluation/Strategy/Matrix Plan was included in 18 of the reports, which amounts to 95% of the total reports. Finally, Performance Measurement Challenges were included in 12 reports, which amounts to 63% of the total.

Overall, six of the 15 key components of a PM strategy were covered in 100 percent of the PM strategies developed. The remaining nine components were not consistently covered. The most challenging component appears to be "reporting burden" as 16 PM strategies did not address this issue. According to the Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contributions, reporting burden involves the simplification of the reporting and accountability regime to reflect the circumstances and capacities of recipients and the real needs of the Government and Parliament. The next most challenging component was "PM Strategy alignment to the Program Activity Architecture (PAA)" – 12 PM strategies did not include a discussion of this topic. Eight PM strategies did not discuss "performance measurement data risks" and seven did not cover "performance measurement challenges".

In June 2010, EPMRB proposed an Indicator Mapping Project to take measure of the PM strategies developed to date and examine their linkage/contribution to overall departmental reporting and assess whether the indicators selected tell a coherent performance story for the Department. The Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program (Umbrella Infrastructure PM Strategy) was used as a pilot. The focus was to:

- Validate logic and outcomes;

- Validate, refine and, where possible, streamline indicators to ensure focus on key outcomes and reduce duplication, redundancies and unnecessary reporting;

- Ensure alignment of outcome statements and indicators with PMF and other planning and reporting requirements (e.g. RPP/DPR, quarterly reports, business plans, etc.);

- Clarify and validate data collection requirements; and

- Map inter-connections of programs across the PAA.

The results of this pilot revealed that indicators could be streamlined and reduced by one third, strengthened and validated, be applied across reporting frameworks/requirements, and resulted in a 10-step data implementation plan.

The umbrella PM Strategy for the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and five approved sub-strategies were targeted for a similar mapping exercise. An initial analysis of these PM strategies found more that 177 indicators across 16 unique outcome statements with an average of 11 indicators per outcome. This mapping project did not proceed because of ongoing program redesign, program interest and staffing changes within the PM team.

Outside of EPMRB, there has also been progress on performance measurement in the Department. The Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) was first conducted in 1991 to collect information not covered in the 1991 Census of Population. This voluntary, post-censal survey became an essential part of the Aboriginal data landscape and was repeated in 2001 and 2006. The survey provides data on the social and economic conditions of Aboriginal people in Canada. More specifically, its purpose is to identify the needs of Aboriginal people and focus on issues such as health, language, employment, income, schooling, housing, and mobility. In 2010-2011, some developmental work began to identify areas for improvement for the next iteration of the survey; including how to better align the survey with priorities and how to increase engagement and participation of First Nation communities.

In September 2010, the Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector received preliminary approval from TBS to develop the Education Information System (EIS). It is anticipated that the system, which is intended to integrate all education-related information and reporting processes, will track performance, measure success, and support continuous program improvements.

Other data management systems are also under development. The Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program developed the Integrated Capital Management System to better track program/project information. For the First Nations Child and Family Services Program, the Alberta region is developing an improved data management system (in early stages), that will become a national system.

AANDC has a current Information Management Strategy and implementation plan that identifies departmental business objectives, program and service outcomes, operational needs and accountabilities, and information management policy requirements. The IM Strategy is partially integrated with other corporate strategies and plans. Some programs (e.g., Consultation and Policy) are addressing their lack of an integrated information system by reviewing and revising all data collection instruments, identifying meaningful and realistic outcomes, indicators and targets through the development of the PM strategy, and developing information management systems.

Despite efforts identified above, the 2010 Corporate Risk Profile determined that, "INAC will not make sufficient progress to improve access to timely, pertinent, consistent and accurate information to support planning, resource allocation and programming decisions, monitoring/oversight, and to fulfill accountability, legal and statutory obligations". Risk factors driving this finding and the departmental response are as follows:

Table 2: Risk Drivers and Response related to Information for Decision Making Risk as identified in the 2010 Corporate Risk Assessment

| Risk Drivers | Response |

|---|---|

|

|

By December 2010, the EPMRB Performance Measurement team had expanded to five full-time equivalents comprised of one manager and four analysts dedicated to providing support for the development of PM strategies (e.g., coordination of internal consultations, component pieces and quality assessment). In March 2011, a strategic change took place and individual members of the PM team were integrated into different evaluation teams.

The following sections examine the impact of the actions by EPMRB and others in 2009-10 and 2010-11 on the ten key attributes of a quality performance measurement system.

2.1 Leadership

Leadership from the senior levels of an organization is critical to the success of performance measurement. The executive level needs to be involved and needs to be seen as being involved, and needs to actively support a culture of performance measurement throughout the Department. Commitment at the senior level is needed before program managers can be expected to take ownership of evaluation results and embrace performance measurement as a means of continuous improvement (Benchmarking Report).

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "leadership" is being measured. "Leadership" ranks in the "attention required" category on the scale, but the ranking is high on the scale within this category, closer to the "acceptable" category.)

Between April 2009 and March 2011, the EPMRC reviewed or approved 19 PM strategies. This was the result of efforts to strengthen the engagement and commitment of senior management through a formal approach to performance measurement. Program Directors General and ADMs were also engaged in performance measurement planning through the annual update of the Evaluation and Performance Measurement Plan and the approval process for PM strategies submitted to the EPMRC. The majority of senior managers interviewed were able to demonstrate knowledge of PM activities underway within their sectors and an awareness of PM activities being pursued in other areas of the Department. Overall, they expressed a keen interest in performance measurement and indicated support for advancing PM activities in the future. Senior managers also appreciated knowledge gained through the discussion of PM activities at the EPMRC.

Additional feedback suggests that more can be done to engage AANDC staff. According to those interviewed, staff need to be more aware of what performance measurement means in relation to their work, including a better understanding of the value of quality performance data for their programs and the Department. Similar comments were noted during the focus group session with program representatives.

Assessment

Senior managers that are strong leaders in the area of performance measurement believe in managing for results and recognise its importance, have a vision regarding managing for results, identify strategic objectives and actions to establish a culture of managing for results and provide the necessary support to staff to achieve objectives. The findings above demonstrate that governance has improved management understanding and engagement in PM processes, but demonstrations of real leadership are inconsistent. With senior management and program representatives indicating a disconnect at the working level, it would seem that a vision, if one exists, has not been communicated throughout the Department. For this reason, AANDC was ranked with "opportunity for improvement" in this area.

2.2 Roles and Responsibilities

Clear roles and responsibilities, for all individuals involved, need to be well articulated and understood. Individuals at all levels, from the recipients, managers, regional offices, internal services and executives, need to understand their roles and accountabilities (Benchmarking Report).

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "clear roles and responsibilities" is being measured. Clear roles and responsibilities ranks in the "acceptable" category of the scale, but sits closer to the "opportunity for improvement" segment of the scale.)

The Department made some progress in capturing the roles and responsibilities associated with performance measurement; namely, the development of performance measurement strategies. EPMRB's Guidance for Program Managers on Performance Measurement Strategies provides information on the management responsibilities outlined in the Policy on Evaluation and associated directive, as well as the role that EPMRB and other internal partners can take during the planning, development and implementation of PM strategies.

Feedback received from participants to the Performance Measurement Collaboration workshop suggests that this exercise was well received. Several participants indicated that in attending the workshop they had increased their understanding of their role as well as that of their colleagues.

However, progress on roles and responsibilities received mix reviews from interview and focus group participants. Consistent with some of the comments previously discussed in Section 2.1, respondents expressed reservations with the extent to which roles and responsibilities associated with performance measurement were clear at all levels throughout the organization. With specific reference to the PM strategy development and implementation processes, participants in the focus group indicated that they found EPMRB's guidance document to be a good starting point, but that a more detailed articulation of roles and responsibilities reflective of operational requirements and decision-making authorities was required.

Several participants noted the need for clarity between the roles of EPMRB and the SPPD. During the focus group session, program representatives also identified difficulties securing support from internal partners during the PM strategy development process. The reasons for this remain unclear, but the frequency with which it was raised by participants suggests that roles and responsibilities and the commitments in time and resources associated with these tasks, are not well understood.

Assessment

Two important steps to assure that roles and responsibilities in the development and implementation of PM strategies are clear: 1) roles and responsibilities are well documented and communicated; and 2) managers, staff and partners clearly understand roles and responsibilities. It is clear that some initiatives, including the guidance document and workshops with internal partners, have achieved some success in articulating roles and responsibilities related to the development of PM strategies. For this reason, "acceptable" was selected for this area.

2.3 Community Needs

The needs and capacity of the community, which is the target audience for programs and activities, must be integrated into the planning process. Designing programs that have incorporated community input can be expected to resonate with the audience. Community involvement should also mean that realistic performance measures and targets can be established at the outset and that they will be clearly understood by all parties before the programming activities begin. Communities will be more motivated to participate in the performance measurement processes if they can see a community focus in the programming and the value of their participation in the performance measurement and reporting processes (i.e. measuring what matters to them).

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "the needs and capacity of the community" is being measured. Community needs ranks in the "attention required" category of the scale, at the halfway point within this category.)

The Department took steps to promote the engagement of communities/program recipients to ensure that PM activities reflect the needs and capacity of the communities served by its programs. Community engagement is endorsed by EPMRB during introductory presentations with programs. In addition, the guidance document emphasizes the importance of consulting with regional program representatives and recipient groups and communities to solicit their insights on indicator development, data availability, data collection, monitoring and reporting requirements. The Thematic Indicators Project also identified indicators that meet community needs, while addressing the broader performance goals of the Department.

Prior to submission to the EPMRC, EPMRB, with input from internal partners, assesses draft PM strategies against several criteria, including the extent to which the program consulted with key stakeholders during PM strategy development. This assessment is the basis of a covering note, which accompanies the PM strategy to EPMRC. Seven of the 19 cover notes submitted to EPMRC in 2009-10 and 2010-11 recommended further engagement of external partners and stakeholders and three indicated that significant work had occurred during the development of the PM strategy. It is not clear how the remaining nine PM strategies measure up, as the assessment forms in which the cover notes are based on were not always updated to reflect changes in the final version of the PMstrategy. In addition, a number of assessments could not be located. At the time of this report, no data was available to determine the impact of the Department's consultative approach on the quality and use of the performance information in communities.Assessment

Two areas related to community needs were advanced for future action in the 2009 Benchmarking Report: advancement of the planned APS consortium and ongoing consultations with regions and target populations in the development of PM strategies.

Funding was approved in Budget 2011 for the fourth generation of the Aboriginal Peoples Survey.

A limited number of external partners and stakeholders have been engaged in the development of PM strategies. Given the importance of the alignment of PM strategies with the information needs and data collection capacity of service delivery agents, and the lack of information on data needs, use and capacity in communities, AANDC is ranked "attention required" in this area.

2.4 Alignment with Strategic Direction

Performance measures need to be aligned with the strategic direction of an organization in order for the organization to demonstrate the extent to which it has achieved its strategic objectives. Supporting systems also need to be aligned.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "alignment with strategic direction" is being measured. "Alignment with strategic direction" ranks in the "acceptable" category on the scale, but sits close to the "opportunity for improvement" category.)

The June 2010 Indicator Mapping Project served as a check to verify the alignment of PM strategies with the PMF and other planning and reporting requirements (e.g. RPP/DPR, quarterly reports, business plans, etc.). As mentioned, the pilot project identified overlaps and redundancies related to community infrastructure. Inconsistencies and a lack of alignment between the PAA, PMF, business planning cycle, quarterly reporting and PM strategies continue to be an issue.

More recently, the Branch has undertaken joint initiatives with SPPD to help increase awareness of the planning and reporting considerations associated with developing or revising a PM strategy. For example, in February 2011, EPMRB and SPPD attended a National Annual Conference hosted by the Emergency Management Assistance Program. Representatives from the two groups provided complementary presentations in relation to the steps associated with revising the program's PM strategy, and how the work connects with the 'big picture'. Feedback received during data collection for this report suggests that there is a demand for more initiatives of this kind. According to interview and focus group participants, while processes have been established for the development of PM strategies and the PMF, the linkages between these two tools are not well documented or understood.

While interview and focus group participants identified that the PAA provides a consistent direction for all programs, they also noted that PAA alignment is not always present in Program PM strategies. Furthermore, some perceive that a disconnect exists between authorities, programs and the PAA and that changes to the PAA impact Program PM strategies and vice-versa, which increases workload and delays. Changes to the PAA and PM strategies also make it difficult to monitor changes over time or to demonstrate progress towards stated outcomes.

Assessment

Some success has been achieved in connecting program performance stories to the strategic direction of the Department as recommended in the 2009 Benchmarking Report. For this reason, "acceptable" was assigned. However, there is still a need to improve the alignment of PM strategies with strategic direction, fundamentally through the MRRS (PAA and PMF) but also through integrated planning. Continued collaboration between EPMRB and SPPD is encouraged to strengthen the linkages between PM and results at the strategic outcome level.

2.5 Credible Performance Information

For a performance measurement system to be of value, there must be confidence in the resulting information. Users will be confident in the information if it is credible; in order to obtain credible information, effective planning is required. The performance measurement strategy or framework provides the means for identifying and gathering the performance measures required for results-based management.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "credible performance information" is ranked as "attention required.")

A lack of performance data continued to be an issue at AANDC. The 2010 study "Informing the Future: Trend Analysis of Past AANDC evaluations" analysed 32 evaluations completed between 2007-08 and 2009-10, and found the most frequent recommendations are related to performance measurement, monitoring and reporting. Data issues identified include: a general lack of data, difficulty gathering or analyzing existing data, lack of indicators or accurate measures, biased or unreliable data, poor reporting on results or no reporting plan, lack of cost-effectiveness data, insufficient baseline data, and a lack of regional data. It is important to note that these data weaknesses refer to performance data, which can be used to assess whether a program has achieved stated objectives or outcomes. Output data (measurements of products or services), on the other hand, are readily available.

The Department continues to pursue efforts that shift the focus toward a discussion of outcomes, the development of more meaningful indicators, the identification of baselines and targets, and more streamlined reporting. At the program level, these efforts are facilitated by a standardized approach to performance measurement strategies that is endorsed by EPMRB. The guidance document remains one of the key reference tools used to support programs in this respect.

Although extremely reliable, concerns were raised about the suitability of the Census and Community Well-Being Index for results measurement due to issues of frequency and timeliness. Census data is collected on a five-year cycle, and is released a year or more later.

To further increase the availability of credible performance information, AANDC pursued the development of formal data collection systems for large-scale departmental programming such as the EIS.

Assessment

Continued work is needed to address data issues in the Department. The participation of on-reserve communities in the APS (as proposed in the 2009 Benchmarking Report) is critical. In addition, AANDC needs access to other reliable primary and secondary sources of data that are produced on an annual or semi-annual basis that links to performance objectives.

The 2009 Benchmarking Report highlighted the importance of performance measures that are aligned with program outcomes, have established baselines and clear performance targets, are disaggregated, and are easily accessible. All of these concepts were incorporated into the INAC Guidance for Program Managers on PM Strategies. However,until PM strategies and information management systems are implemented, there will continue to be a lack of credible performance data. For this reason, AANDC is ranked "attention required" in this area.

2.6 Implementation

The performance measurement strategies must be fully implemented for the benefits to be realized. Performance information needs to be collected effectively and regularly from all identified sources. The approach must take into account the twin focuses of managing responsibility and balancing capacity.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "implementation" is being measured. Implementation is ranked as "attention required.")

Although the INAC Guidance for Program Managers on PM Strategies specifies that a follow-up on PM strategies will occur on an annual basis, by March 2011, EPMRB had not yet implemented a formal process for monitoring the implementation of PM strategies.

A number of challenges to the implementation of PM strategies were identified in the literature and in interviews:

- Problems gathering or analyzing existing data, lack of indicators or accurate measures, biased or unreliable data.

- Inability to access data from other departments, First Nations, or other third-party stakeholders to support PM strategy implementation.

- Data capture is limited due to lack of structures, tools, or tracking mechanisms. Focus group participants indicated more data systems to support data collection and management would help improve PM.

- Lack of capacity (in both program recipients and program managers) to collect, report, and analyze data.

- Interview respondents indicated the fragmentation of data systems is a challenge.

- The impact of PM strategies on the reporting burden is not well understood.

The identification of risks associated with the implementation of PM strategies has helped and several PM strategies have illuminated the value of integrating risk with PM work to help ensure necessary infrastructure is in place to support effective implementation. However, for many, the implementation of PM strategies continues to be complicated by a lack of data.

Assessment

Implementation involves the creation of systems and processes for data collection, storage, monitoring and verification, and the integration of performance measurement data into management decisions, policy development and reporting.

The Benchmarking Report committed to the implementation of PM strategies as a replacement to the RMAF/RBAFs. However, findings suggest that the focus remains largely on the development of PM strategies. As a result, AANDC is ranked "attention required" in this area. A formal process for monitoring the implementation of PM strategies is required as lessons learned through this process can then be fed into future guidance.

2.7 Capacity

Employees and other stakeholders need to have the capacity to fulfill the requirements for performance measurement. Capacity issues include: training and education (e.g. performance measurement, reporting and other relevant skills and competencies); tools and guidelines; infrastructure or IM/IT systems in place; and, adequate resources, including both financial and human resources.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "capacity" is being measured. On the scale, "capacity" is ranked as "opportunity for improvement," but sits closer to "acceptable" on the scale.")

EPMRB has taken steps to develop capacity in performance measurement through workshops, studies, presentations and the guidance document, however, the shift to a results-based approach has been hindered by capacity issues across the board in EPMRB, with internal partners, programs, regions and within First Nation communities.

Interviewees and focus group participants raised concerns about the limited resources available through EPMRB and other internal partners to assist with the development and implementation of PM strategies. A lack of consistency in advice was also noted. It was felt that program staff are not as experienced in developing/implementing PM strategies and needed consistent advice and more training and awareness at all levels, particularly for those with PM responsibilities and needs.

It was generally felt that the collaborative approach internally helped to support capacity, but that greater coordination was needed to support a horizontal view of capacity. A more proactive approach to capacity was suggested with additional resources to support data collection and management and the maintenance of data systems. Similarly, there was confidence in the competence of recipient organizations but it was noted that they do not have the resources for data collection. In addition, some of the smaller Northern communities do not have sophisticated electronic information systems. It was suggested that the Department develop a strategy to address capacity issues and a common course or tools on PM for all staff.

It was noted in the literature that data-information management systems are being developed and implemented to reduce the capacity limitations, however, many programs/stakeholders continue to keep shadow systems. Using/maintaining dual systems contributes to the capacity limitation. Similarly, the introduction of new data systems sometimes demands more training than expected by some programs.

Assessment

Capacity development involves the assignment of adequate resources to performance measurement and training on PM and results-based management. Given that a shift towards increased use of performance data implicates the whole Department, a more coordinated approach to capacity development is required for all levels and with internal and external partners to ensure consistency and quality.

EPMRB went beyond actions proposed in the 2009 Benchmarking Report to complete the Thematic Indicators Research Project and collaborate with internal partners in the development of PM strategies. However, "opportunity for improvement" was assigned because capacity in program areas continues to be limited.

2.8 Performance Information is Used

The performance information that is gathered needs to be used to fulfill policy requirements, support evidence-based decision making and meet various reporting requirements. Most directly, performance information is used to monitor progress on programs and inform evaluation work. More broadly, performance information is used as part of a continuous improvement process in quality management.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, the way in which "performance information is used" is being measured. It ranks in the "attention required" category of the scale, at the halfway point within this category.)

There is a strong perception that AANDC collects lot of information, but unfortunately, much of it is unsuitable for performance reporting. Data collected focused on outputs rather than outcomes and an inability to rollup data is often identified. Program reporting and activity reports are not oriented to assist in assessing performance or impacts and do not address organizational capacity or community level impacts. The document and literature review suggested that the use of performance information for evaluation is limited, and if performance information was more credible, it would lead to evaluations of higher quality. Further, PM strategies are perceived as informing TB submissions and Memoranda to Cabinet (MCs), streamlining reporting and information management.

Despite weaknesses with data being collected, analysis of data has guided decision making and informing the redesign/design of programs and data management systems. About 50 percent of focus group participants could identify examples of where data was being used. Feedback from interviews and the focus groups reveal that available information is being used at the sector and senior management levels, however, it is primarily used for reporting to central agencies through rollups for various reports, such as the DPR, Management Accountability Framework (MAF), TB submissions, Strategic Review, and regular reporting.

To summarize, data collected is generally used but is focused on outputs (products and services) and is unsuitable for use in managing for results and assessing program impact.

Assessment

Performance information can be used for planning results, measuring progress toward results, monitoring and mitigating risk, evaluation, reporting at the program, departmental and/or Cabinet levels, and decision making. The 2009 Benchmarking Report focused on the need to communicate the use and value of performance data so that employees would understand its importance.

Considering the findings above, it is evident that numerous sources of information exist, and managers are using available information for decisions and reporting, however, it would appear that data available is not integrated with results. As a result, a ranking of "attention required" has been assigned.

A review of what data is being collected and why, similar to the Mapping Project, would identify information that is being collected and not used or is unsuitable for performance reporting. An assessment regarding to what extent PM information is being relied upon, such as a formal process to follow-up on the implementation of PM strategies, could prove beneficial toward identifying how to maximize information use.

In addition, increased credibility and quality of indicators should contribute to an increase in the use of PM information.

2.9 Communication

Ongoing communications between all people involved from all levels and areas of responsibility, internal and external, is important. Key performance information needs to be cascaded through an organization so employees understand its significance and their role in achieving expected results.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "communication" is being measurement. "Communication" ranks in the "opportunity for improvement" category on the scale, closer to the "acceptable" segment of the scale than the "attention required" segment.)

As described in previous sections, a number of tools and processes were developed in 2009 and are used regularly to communicate, promote, and increase awareness of performance measurement in AANDC. In addition, regular reporting to the EPMRC has contributed to knowledge and commitment at the senior management level. The document review reveals a greater sense of PM awareness within the organization. However, the extent to which the overall messages are sufficiently reaching program staff is unclear.

A disconnect appears with staff at lower levels (analysts collecting the data) as to their understanding of what the data is being used for and what their contributions are to the PM strategies and overall accountability. Focus group participants indicated that processes are not well understood by programs and many programs do not know what a PM strategy is. Overall, channels appear less open from senior level to front-line, between EPRMB and the programs, and between the PM strategies and corporate planning/reporting. Enhanced internal and external communication of performance measurement was identified as a need.

In terms of external communication, AANDC has endeavoured to promote communication with First Nation communities, Inuit, and other external partners, through engagement activities, however, there seems to be little organization or consistency as to what, when and how PM-related communication occurs.

Assessment

Successful communications efforts are evidenced by the tools and processes in place, the extent to which management and staff recognize the value of PM, and actions taken.

Workshops and meetings supported by EPMRB address the recommendation in the 2009 Benchmarking Report to strengthen horizontal communication across the Department, but has had an inconsistent impact in the Department. Communication with First Nations, Métis and Inuit organizations and other government departments (OGDs), also suggested in the Benchmarking Report, has been inconsistent and limited. As a result, "opportunity for improvement" has been assigned.

Given the horizontal nature of performance measurement and the involvement of external stakeholders, AANDC would benefit from greater communication that promotes understanding of PM in the bigger scheme of a results-based culture.

2.10 Culture

A culture that focuses on results, where the purpose and value of performance measurement is understood and employees have the required skills, is needed in order to create a supportive operating environment.

(This figure is a scale which represents four categories in the following order, from left to right: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. On this scale, "culture" is being measured. On the scale, "culture" is ranked as "attention required," and sits at the halfway point within this segment of the scale.)

As described in previous sections, progress has been made in nine areas, which contribute to a PM culture, however, a significant amount of capacity and awareness development is still required.

A review of letters of recommendation prepared for PM strategies presented to EPMRC shows that PM strategies submitted have had a number of identified weaknesses. However, there is a lack of incentives to improve performance measurement strategies.

According to focus groups, the PM culture is still very new and there is much opportunity for growth. There is a clear willingness of staff to work/collaborate on PM strategies and a suggestion that the focus on development needs to shift to implementation.

Assessment

The culture at AANDC has a transactional focus where the primary interest is to get funds out to beneficiaries. A PM culture focused on results where the purpose and value of PM is understood is in an early stage of development at AANDC. In the 2009 Benchmarking Report, it was suggested that the Department create incentives or remove disincentives to PM so that employees take ownership of results. Including performance measurement expectations in executive contracts was advanced as a possible step. No decision has been made on this issue.

Given that "attention required" was assigned in previous sections to the critical areas of leadership, implementation, use, and data credibility, "attention required" was also assigned for culture.

3. Conclusion

3.1 Summary of Key Findings

In 2009-10 and 2010-11, AANDC made moderate advances in the ten key attributes of a quality performance measurement system as defined in the 2009 Benchmarking Report. EPMRB outlined principles for developing PM strategies and communicated these principles through awareness and capacity building exercises and guidance documents. The established governance structure engaged internal organizations, defined roles and responsibilities, and secured commitment of senior executives. Additional projects and studies have advanced understanding of indicators, identified areas of overlap and duplication, and tracked progress to date.

In other sectors, several program areas, including education, infrastructure, consultation and policy, as well as child and family services have developed, or are developing, information management systems that will capture performance information. In addition, the APS has been a key source of information on a broad array of demographic and socio-economic characteristics of First Nations, Métis and Inuit. In summary, AANDC has established a foundation for advancing performance measurement in the Department.

Based on information collected through the document and literature review, interviews and focus groups, the ranking of AANDC's performance in each of the 10 key attributes identified in the Benchmarking Report is as follows:

Text description of The ranking of AANDC's performance

Scale used to rank AANDC's performance

This figure is a depiction of the scale used to rank AANDC's performance in each of the 10 key attributes identified in the Benchmarking Report. From left to right, the rankings on the scale are as follows: attention required, opportunity for improvement, acceptable, and strong. The following attributes were ranked under "attention required": Community needs, credible performance information, implementation, performance information is used, and culture. The following attributes were ranked under "opportunity for improvement": Leadership, capacity, and communication. The following attributes were ranked under "acceptable": Roles and responsibilities and alignment with strategic direction. No attributes were ranked as "strong."

Overall, it was found that actions taken to date have created a foundation for future activities, however, improvement is needed in all ten attribute areas. Specific findings for the 10 key attributes areas are summarized below:

- Leadership

Governance has improved management understanding and engagement in PM processes, but demonstrations of real leadership are inconsistent. With senior management and program representatives indicating a disconnect at the working level, it would seem that a vision, if one exists, has not been communicated throughout the Department. Senior managers must recognise the importance of managing for results, develop a vision, build capacity and take action to establish a culture of managing for results. - Roles and Responsibilities

Some initiatives successfully articulated roles and responsibilities related to the development of PM strategies, however, some staff still do not clearly understand the roles of EPMRB and SPPD. In regards to the implementation of PM strategies, the extent to which roles and responsibilities have been communicated and the level of understanding of internal and external partners remains unknown. Better documentation and understanding of roles and responsibilities are needed at AANDC. - Community Needs

A limited number of external partners and stakeholders have been engaged in the development of PM strategies. It is important that PM strategies be aligned with the information needs and data collection capacity of service delivery agents. - Alignment with Strategic Direction

Some success has been achieved in connecting program performance stories to the strategic direction of the Department, however, a strengthened collaboration between EPMRB and SPPD is encouraged to ensure linkages between PM and results at the strategic outcome level. - Credible Performance Information

Until PM strategies and information management systems are implemented, there will continue to be a lack of credible performance data. Continued work is needed to address data issues in the Department. The participation of on-reserve communities in the APS is critical. In addition, AANDC needs access to other reliable primary and secondary sources of data that are produced on an annual or semi-annual basis and link to performance objectives. - Implementation

AANDC has focused primarily on the development of PM strategies, not their implementation. A formal process for monitoring the implementation of PM strategies is required. - Capacity

Capacity development involves the assignment of adequate resources to performance measurement and training on PM and results-based management. A more coordinated approach to capacity development is required for all levels and with internal and external partners to ensure consistency and quality. - Performance Information is Used

Senior management is using performance information for external reporting, but not for results-based management. Numerous sources of information exist, but it is not apparent if these sources are strategically coordinated or integrated with results. A review of what data is collected and data needed to report on results is needed. - Communication

Workshops and meetings supported by EPMRB have strengthened horizontal communication across the Department. Communication with First Nations, Métis and Inuit organizations and OGDs, has been inconsistent and limited. AANDC would benefit from greater communication that promotes understanding of PM in the bigger scheme of a results-based culture. - Culture

A PM culture focused on results where the purpose and value of PM is understood is in an early stage of development at AANDC. Incentives and disincentives would assist the advancement of a results-based management culture in the Department.

3.2 Next Steps

To address the issues above and promote the growth of PM culture at AANDC, EPMRB is committed to:

- Wider engagement at all levels to improve leadership, identify incentives to using performance information, and enhance capacity;

- Promoting enhanced collaboration with internal and external partners to ensure that better information is available to support effective performance measurement and management for results;

- Developing a communications plan, which targets different audiences to encourage the acceptance of performance measurement as an essential tool for management;

- Analysing data currently collected, data needs for performance reporting and reducing reporting burden; and

- Introducing a follow-up strategy on the implementation of PM strategies. This strategy will contribute to the assessment of the state of performance measurement at AANDC and will provide an exchange forum for programs and partners allowing identification of barriers, best practices, needs for communication and training products.

References

Alberta Native Friendship Centres Association. (2009). Common Ground: An Aboriginal Relationship Agreement Framework: Facilitator's Toolkit.

Alkin, M.C. & Daillak, R. H. (1979) Study of Evaluation Utilization. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Jul. – Aug), pp. 41-49

Alkin, M.C & Taut, S. M. (2003). Unbundling Evaluation Use. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 29, pp. 1-12.

Aucoin, P. (2005). Decision-Making in Government: The Role of Program Evaluation. Discussion Paper. May 2005. Retrieved on June 30, 2009.

Auditor General of Canada. (2000). Chapter 19—Reporting Performance to Parliament: Progress Too Slow.

Bernstein, D. J. (1999a). Performance Measurement: Does the Reality Match the Rhetoric? A Rejoinder to Bernstein and Winston. American Journal of Evaluation, 20(1), 101-111.

Bernstein, D. J. (1999b). Comments on Perrin's effective use and misuse of performance measurement. American Journal of Evaluation, 20(1), 85–93.

Boris, B. V. and King, J.A. A checklist for Building Organizational Evaluation Capacity. Retrieved from the Internet on March 28, 2010.

Borys, S. (2008, February). Challenges facing the federal evaluation function: Attracting (and keeping) the next generation of evaluators. Presentation at PPX Breakfast Series, Ottawa, Canada.