Archived - Review of the Performance of the Emergency Management Assistance Program during the 2011-12 Manitoba Floods

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Final Draft: June 2012

Final Summary Report: January 2013

Project Number: 1570-7/12001

PDF Version (405 Kb, 47 Pages)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Review Methodology

- 3 The 2011-12 Manitoba Flood: A Chronology from the Media

- 4 Review Findings - Relevance

- 5 Review Findings - Performance

- Appendix A: Red River's highest flood levels between 1800 and 1999

- Appendix B: EMAP Funding Process

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| ADM |

Assistant Deputy Minister |

| CIB |

Community Infrastructure Branch |

| DM |

Deputy Minister |

| EIMD |

Emergency and Issues Management Directorate |

| EMAP |

Emergency Management Assistance Program |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| HQ |

Headquarters |

| MANFF |

Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters |

| NFPA |

National Fire Protection Association |

Executive Summary

This report presents the results of the Review of the Performance of the Emergency Management Assistance Program (EMAP) during the 2011-12 Manitoba Floods. Throughout 2011, Manitoba experienced what was characterized as a one in three hundred year flood. Much of the southern half of the province was flooded; notably this included 27 First Nation communities. The purpose of the review is to assess the Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) emergency management activities undertaken for the mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from the 2011-12 floods in Manitoba in order to develop lessons learned and facilitate improvements to future programming related to emergency management.

EMAP is intended to protect the health and safety of First Nations members when faced with natural disasters and damage or destruction of community infrastructure and houses by natural disaster or accident; assist in the remediation of essential infrastructure and houses through timely assessment of emergency needs and facilitation of an appropriate emergency response from other areas within the Department; and support communities on a compassionate basis through continuation of search and recovery activities associated with lost persons.

The AANDC Emergency and Issues Management Directorate (EIMD) is responsible for the overall management of EMAP and the AANDC regional offices are responsible for working directly with stakeholders to deliver the program. The total funding provided to address the Manitoba flood was $84,451,088 (this included $3,242,035 during 2010-11 and $81,209,053 during 2011-12).

Emergency management situations on First Nation reserves are generally dealt with in collaboration with provincial governments by utilizing the provincial emergency response organizations and their supporting processes to coordinate a response in First Nation communities. This collaboration is achieved through arrangements between AANDC and most provinces. The situation in Manitoba is different than most of the other AANDC regions because AANDC and the Province of Manitoba do not have an agreement in place. As a result, the Manitoba regional office is responsible for working directly with First Nation communities to coordinate a response during emergency situations and therefore it enters into a funding agreement with individual First Nations.

In general, First Nations in southern Manitoba are exposed to significant flood hazards and display a number of characteristics that increase their susceptibility to flood damage. The need for assistance notably rests in the propensity for flooding in southern Manitoba, poor community planning, limited/poor flood control infrastructure, the lack of financial resources and technical expertise, as well as lack of clarity in systems, processes and mechanisms for dealing with emergency situations. The overly exposed conditions of First Nation communities in southern Manitoba coupled with limited capacity, means that First Nations required, and will continue to require, significant assistance when faced with emergencies.

During the 2011-12 Manitoba flood, EMAP assisted 27 First Nation communities with flood fighting and the evacuation of 12 communities. EMAP succeeded at protecting the immediate health and safety of First Nation communities. However, with respect to protecting community infrastructure and long-term health and safety issues (such as the development of mould in houses that were flooded), success is much more difficult to assess, given the circumstance and the particular context of this dramatic flood.

Although EMAP began in 2005, it continues to evolve. The 2010 Evaluation of EMAP recommended that AANDC define relationships with all external stakeholders and put in place appropriate governance structures and agreements to ensure fulfillment of its responsibilities. The recommendation placed particular emphasis on the program delivery mechanisms and structures related to the four pillars of emergency management: mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery. This review confirms that EMAP has yet to fully address this issue. Notably, the governance structure remains unclear and program delivery mechanisms have not been developed for conducting risk assessments, developing mitigation strategies, developing and testing emergency management plans or responding to events.

It became clear that the emergency management system was being stretched to the limit of its capacity and EMAP was not able to muster the required additional "surge" capacity to deal with the situation in an effective way. Finally, the lack of a clearly defined governance structure within the program has affected the cooperation with stakeholders that is necessary for an effective First Nation emergency management system in Manitoba.

What is clear from the Manitoba case is that EMAP has been forced to react and that it limits its ability to address the long-term and systemic issues that First Nations face when confronted by natural disasters.

To address these issues, it is recommended that:

- EMAP should develop better linkages with other programs within AANDC to ensure an effective system for supporting long-term solutions for emergency management hazards and community resilience.

- EIMD should develop guidelines for First Nation Emergency Management Plans that include protocols for how a First Nation can access assistance when their internal resources are overwhelmed. Once the guidelines are in place, the AANDC Manitoba regional office should work with First Nations at highest risk to update their plans and maintain copies of the plans to form the basis of future coordination work.

- EIMD and the AANDC Manitoba regional office should explore how to scale emergency management roles and responsibilities based on the size and magnitude of emergency events, including when and how Headquarters should become involved in decision making during a response.

- The AANDC Manitoba regional office should develop the capacity to implement the full incident management system during future emergencies as stated in the AANDC Manitoba Regional Office Emergency Management Plan.

- In consultation with the AANDC regional offices, EIMD should develop clear procedures, protocols or guidelines for conducting risk assessments and supporting emergency responses (including activities such as flood fighting and evacuations).

- Once the governance structure and processes have been clarified, EIMD and the AANDC Manitoba regional office should engage with its partners to develop the necessary partnerships for an effective emergency management system.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Review of the Performance of the Emergency Management Assistance Program during the 2011-12 Manitoba Flood

Project #: NCR-A 1570-7/12001

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) EMAP should develop better linkages with other programs within AANDC to ensure an effective system for supporting long term solutions for emergency management hazards and community resilience. | Since the 2011 Manitoba floods, EIMD merged with the Community Infrastructure Branch (CIB) and has already begun making important linkages with other departmental programs, particularly with regard to the mitigation and recovery pillars. EMAP will further leverage existing Capital Facilities and Maintenance programming to strengthen risk assessments, mitigation, reporting systems, and promote strategic infrastructure investments (community design, location of new infrastructure, etc). Currently, EMAP is working closely with the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program to develop options to strengthen emergency mitigation activities in on-reserve First Nations communities. AANDC will also leverage current activities underway within Public Safety Canada. |

Director General, CIB | Ongoing |

| 2) EIMD should develop guidelines for First Nation Emergency Management Plans that include protocols for how a First Nation can access assistance when their internal resources are overwhelmed. Once the guidelines are in place, the AANDC Manitoba regional office should work with First Nations at highest risk to update their plans and maintain copies of the plans to form the basis of future coordination work. | EMAP will develop a national First Nations Emergency Management Manual on roles, responsibilities, protocols and service standards and guidelines on how AANDC regional offices will engage First Nations, provinces and other organizations as well as define roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders. In addition, EMAP will include guidelines related to declarations of states of emergency and how to determine when these are over for First Nations to declare an emergency which will help clarify roles and responsibilities as well as lead to EMAP's increased effectiveness. The AANDC Manitoba regional office and the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters (MANFF) will work collaboratively to strengthen First Nations emergency management plans by developing an emergency management plan template and supporting First Nations during plan development. The AANDC Manitoba regional office will engage to implement a strategy to update and maintain community emergency management plans as well as collect copies of finalized plans for AANDC's records. The AANDC Manitoba regional office will be responsible for overseeing this work. |

National First Nations Emergency Management Manual: Director General, CIB & Director of EIMD Template for First Nations emergency management plans: Associate Regional Director General, AANDC Manitoba regional office Setting out a new process for declaring an emergency: Director General, CIB Overseeing the implementation of strategy to update and maintain First Nations emergency management plans: Associate Regional Director General, AANDC Manitoba regional office |

National First Nations Emergency Management Manual: 2012-2013 (Q4) Template for First Nations emergency management plans: 2012-2013 (Q4) Implement a strategy to update and maintain First Nations emergency management plans: TBD |

| 3) EIMD and the AANDC Manitoba regional office should explore how to scale emergency management roles and responsibilities based on the size and magnitude of emergency events, including when and how Headquarters should become involved in decision-making during a response. | The AANDC Manitoba regional office along with CIB will develop a formalized structure, which identifies a) various emergency thresholds based on the scale of an event; and b) the associated scale of emergency management roles and responsibilities for each threshold. This structure will clarify roles of Headquarters in the decision making process during an event. AANDC Regional Emergency Management Plans will be adjusted to reflect these changes. |

Associate Regional Director General, AANDC Manitoba regional office & Director General, CIB | TBD |

| 4) The AANDC Manitoba Regional Office should develop the capacity to implement the full incident command system during future emergencies. | AANDC Manitoba regional office will develop surge capacity within Manitoba region that aligns with the Incident Command System providing a way of coordinating the efforts of agencies and resources as they work together toward safely responding, controlling and mitigating an emergency incident. In the development of surge capacity, AANDC Manitoba regional office will explore best practices and other regional examples to help develop a surge capacity team that can be both effective and efficient and suits the needs for Manitoba First Nation communities. |

Associate Regional Director General, AANDC Manitoba regional office | TBD |

| 5) In consultation with the AANDC regional offices, EIMD should develop clear procedures, protocols or guidelines for conducting risk assessments and supporting emergency responses (including activities such as flood fighting and evacuations). | AANDC will use existing information about First Nation communities, including First Nations emergency management plans, regional expertise, AANDC General Assessment and inspection reports for infrastructure to develop a risk based model that will support the department and First Nations in implementing appropriate mitigation activities. Conducting community-level risk assessments is a First Nation responsibility and is part of an emergency management plan. AANDC is responsible for supporting First Nations in conducting risk assessments and, in Manitoba, the AANDC regional office will engage to provide this support. |

Risk Assessment Methodology: Director of EIMD Support First Nations in engaging the proper authorities: Associate Regional Director General, AANDC Manitoba regional office |

|

| 6) Once the governance structure and processes have been clarified, EIMD and the AANDC Manitoba regional office should engage with partners to develop an effective emergency management system for Manitoba First Nation communities. | AANDC to develop options to implement an efficient emergency management system for Manitoba First Nations communities. AANDC to continue to participate in bi-lateral negotiations with the Province of Manitoba and for Emergency Management Service Agreements in support of Aboriginal communities in Manitoba, as well as, Public Safety Canada regarding the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements program. |

Development of options: Director of EIMD Bi-lateral negotiations: Director of EIMD & Associate Regional Director General, AANDC Manitoba regional office |

TBD |

I approve the above Management Response/Action Plan

Original signed by:

Ron Hallman

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister

The Management Response/Action Plan for the Review of the Performance of the Emergency Management Assistance Program during the 2011-12 Manitoba Floods were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 22, 2012.

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

This report presents the results of the Review of the Performance of the Emergency Management Assistance Program (EMAP) during the 2011-12 Manitoba Floods. The purpose of the review is to assess the emergency management activities undertaken for the mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from the 2011-12 floods in Manitoba in order to develop lessons learned and facilitate improvements to future programming related to emergency management.

The report is structured as follows: the Introduction (Section one) presents a profile of EMAP; Section two provides an overview of the review methodology; Section three provides an overview of the 2011-12 Manitoba flood; Section four and five present the findings related to relevance and performance; and, finally, Section six presents the conclusions and recommendations. Appendix A and B contain a list of historic floods and the funding process for EMAP respectively.

1.2 Program Profile

This section provides a brief description of EMAP, including an overview of the program objectives, management and resources.

1.2.1 Background and Description

An emergency is commonly understood to be a situation where a community is overwhelmed by unforeseen or extraordinary events such that it can no longer manage using its normally available resources and capacity. Emergencies can be triggered by natural events (such as forest fires and flooding) or human-induced events (such as civil unrest, a train derailment or communicable disease outbreaks).

Within Canada, emergency management roles and activities are carried out in a responsible manner at all levels of society. Responsibilities are shared by the federal, provincial and territorial governments and their partners, including individual citizens who have a responsibility to be prepared for disasters and contribute to community resiliency.Footnote 1 This framework is built upon the assumption that the individual is responsible for dealing with emergencies until their capacity is overwhelmed. At this point, each successive level of government is engaged as the lower level of government is overwhelmed. According to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), First Nation community members are responsible for emergency mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery within their homes and with their families and dependents. First Nations are responsible for emergency management within their community, having an emergency management plan that assigns roles and responsibilities for emergency management, and requesting assistance if their resources are overwhelmed.Footnote 2

AANDC has a longstanding involvement, dating back to the 1960s, in dealing, to some extent, with emergencies relating to First Nation reserves. Over the past 20 years, the specific role of the Department in managing emergencies in these communities has become increasingly defined. The passing of the Emergency Preparedness Act in 1988 made every Minister accountable to Parliament for identifying "civil emergency contingencies that are within or related to the Minister's area of accountability" and for developing a civil emergency plan.

As a result of the Act, AANDC's roles and responsibilities became better defined. The federal government provided AANDC with the authority and resources to support fire suppression services when forest fires (or similar incidents) affected First Nation reserves and allowed the Department, based on compassionate grounds, to provide financial assistance to First Nations for search and recovery activities related to lost persons after the local authority has called off search and rescue.

The federal government established the program's second building block in 2004, when it expanded the 1988 Departmental Authority to include a broader range of activities and services related to emergency management. The Department gained the authority to support a range of activities related to mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery. However, incremental funding was not provided on a permanent basis (A-base) to support this expanded mandate. Rather, the federal government has been providing funding on an ad hoc basis (by requesting supplementary funding through the Treasury Board management reserve on a cost recovery basis).

The passing of the federal Emergency Management Act in 2007 provided further clarifications on the roles and responsibilities of all federal ministers. First, the new act provides a definition of emergency management, which includes the "prevention and mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from emergencies." The Act also requires each minister accountable to Parliament to identify the risks "that are within or related to his or her area of responsibility" and, on that basis, to prepare, maintain, and test emergency plans.

Currently, EMAP is operating under the Terms and Conditions for Contributions for Emergency Management Assistance for Activities on Reserve.

1.2.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

According to the EMAP terms and conditions, the objectives of the Emergency Management Assistance activities are to:

- Protect the health and safety of First Nations members when faced with natural disasters and damage or destruction of community infrastructure and houses by natural disaster or accident;

- Assist in the remediation of essential infrastructure and houses through timely assessment of emergency needs and facilitation of an appropriate emergency response from other areas within the Department; and

- Support communities on a compassionate basis through continuation of search and recovery activities associated with lost persons.

The immediate outcomes from these activities are an improvement in First Nations' emergency preparedness and an increase in their capacity to develop emergency plans. The intermediate outcomes include: improved disaster mitigation response time; facilitation of and reduction in the costs of emergency response and recovery; and increased capacity of First Nations to handle emergencies. The long-term outcomes are to ensure the health and safety of First Nations' members and communities, while improving First Nation emergency management capacity.

EMAP currently contributes to the Federal Administration of Reserve Land program activity under the Land and Economy Strategic Outcome of the AANDC Program Activity Architecture.Footnote 3 A Performance Measurement Strategy is currently being developed to help monitor progress against the stated objectives and outcomes. However, this Performance Measurement Strategy was not in place during the 2011-12 Manitoba floods and therefore, is not included in this review.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The AANDC Emergency and Issues Management Directorate (EIMD) is responsible for the overall management of EMAP. The Directorate provides both policy and operational support for the ongoing implementation and management of the program. AANDC regional offices play a predominant role in managing the program by working directly with key stakeholders (i.e., emergency management organizations, Aboriginal organizations, and band councils).

Emergency management situations on First Nation reserves are generally dealt with in collaboration with provincial governments by utilizing the provincial emergency response organizations and their supporting processes to coordinate a response in First Nation communities. This collaboration is achieved through arrangements between AANDC and most provinces. However, the situation in Manitoba is different than most of the other AANDC regions because AANDC and the Province of Manitoba do not have such an arrangement in place. As a result, the Manitoba regional office is responsible for working directly with First Nation communities to coordinate a response during emergency situations and therefore, it enters into a funding agreement with individual First Nations.

In this context, the AANDC Manitoba Emergency Management Coordinator is responsible for gathering information and directing Manitoba regional operations for AANDC by overseeing additional emergency management personnel within the regional office, communicating with First Nations, coordinating activities between stakeholders involved with supporting First Nations and providing general support for First Nation emergency management activities. The Director of Infrastructure and Housing is responsible for authorizing emergency expenditures and the Associate Regional Director General is responsible for maintaining contact with his counterparts in the provincial government and escalating requests for assistance from other federal departments to AANDC Headquarters (HQ). The Regional Director General is responsible for representing AANDC on the Manitoba Federal Council's Emergency Management Working group and coordinating activities with other federal departments.Footnote 4

The Province of Manitoba may provide assistance to First Nations to the degree that is possible following a request for assistance from AANDC and, in the case of the 2011-12 flood, the province was responsible for reimbursing eligible expenses to First Nations under the Disaster Financial Assistance Program. This program was supported by the Public Safety Canada, Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangement - a federal program that provides financial assistance to provinces and territories during large scale natural disasters.

The Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters is responsible, as a service deliverer for AANDC, for providing support to First Nations around social services required during an evacuation as well as supporting First Nations with the development of community emergency management plans.

First Nations are responsible for emergency management within their communities, having an emergency management plan and requesting the help of AANDC if their resources are overwhelmed. Ultimately, First Nation community members are the beneficiaries of EMAP, however, from an administrative point of view, the program does not provide direct funding to individuals and families. Instead, the funding is provided to either the First Nation or the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters who provide emergency management services to community members (as noted above).

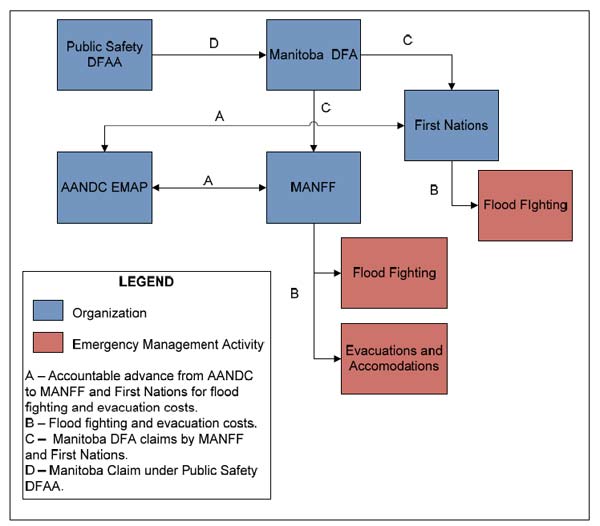

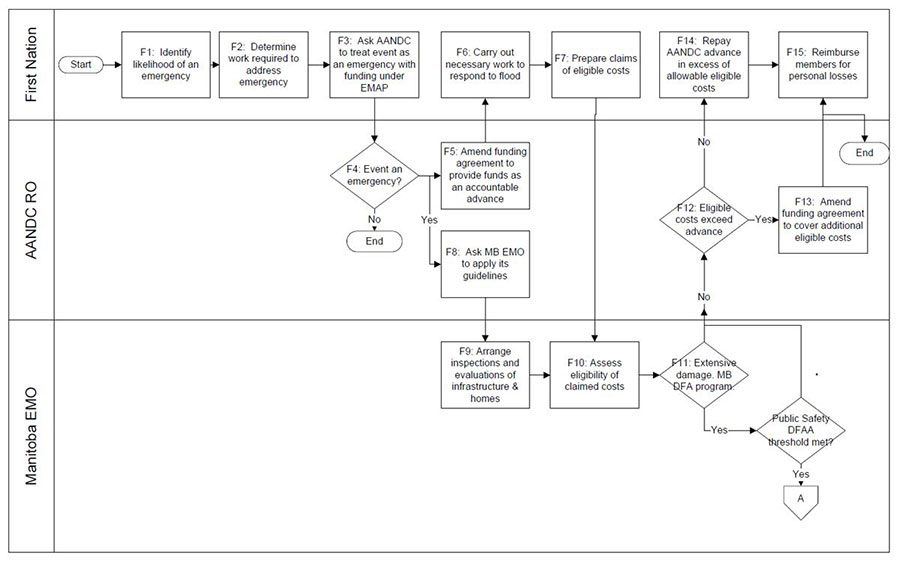

Figure 1 below presents the funding relationship between the various stakeholders and emergency management activities in First Nation communities.

Description of figure 1: Emergency Management Funding Structure for Manitoba First Nations

Figure 1 presents the funding relationship between the various stakeholders and emergency management activities in First Nation communities. EMAP provides an accountable advance to MANFF and First Nations, who provide flood fighting and evacuation services to communities. MANFF and First Nations submit claims for their expenses to the Manitoba Disaster Financial Assistance Program and Manitoba submits a claim of their expenses to the Public Safety Canada Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangement.

1.2.4 Program Resources

The federal government provides ongoing funding to EMAP (A-base funding) in the amount of $18,936,670 per year (for fiscal year 2011-12). This amount includes $16,536,000 in transfer payments (contributions) that are specifically assigned to fire suppression activities. An additional $2,400,670 is assigned to departmental emergency management activities, which includes 22 full-time equivalent employees and their associated operating costs. The Department reallocates existing resources assigned to other programs (such as capital projects) for any additional financial resources needed to support EMAP activities. Where it is no longer feasible for the Department to carry the financial burden, it seeks supplemental funds from the Treasury Board management reserves.

During the 2011-12 fiscal year, AANDC submitted proposals to Treasury Board requesting supplemental funding to address emergency management activities on reserves across the country. The total expenditures to address the Manitoba flood were $78,751,088 (this included $3,242,035 during 2010-11 and $75,509,053 during 2011-12).

2 Review Methodology

2.1 Purpose and Scope

The purpose of the review is to assess emergency management practices during the 2011-12 Manitoba flooding in order to develop lessons learned and facilitate improvements to future programming related to emergency management.

The review examined emergency management activities that were undertaken related to the mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from the 2011-12 floods in Manitoba. This included AANDC policies and procedures related to EMAP funding, as well as the related management practices of AANDC, the Province of Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization and band councils in the affected communities.

2.2 Review Issues

In line with the Terms of Reference, the review examined the following:

- Contributing factors affecting the continued need for emergency management assistance related to Manitoba flooding.

- Performance of EMAP during the 2011-12 Manitoba floods.

- How effective was emergency management (i.e., flood mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery) been at protecting First Nation communities from the Manitoba floods?

- To what extent did the governance structure contribute to effective and efficient emergency management in Manitoba?

2.3 Methods

The review's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following lines of evidence:

Literature Review: This review examined academic literature and documentation pertaining to the drivers of Manitoba floods and expected trends in the future, as well as emergency management models and approaches in the context of flooding and specific concepts pertinent to First Nations (such as vulnerabilities).

Document and file review: A document and file review was conducted to examine foundational documents, implementation documentation, annual reports, financial data (both planned and actual), and other administrative data and information. This also included situational reports, notification reports, summary reports, and lessons learned / after action reports related to the Manitoba floods. The sources of documents included AANDC HQ, Manitoba region and documents from the Province of Manitoba that were publically available through their websites. A sample of three First Nations Emergency Management Plans was also reviewed under this method.

Past reviews, evaluations and audits were also examined, including the 2010 Evaluation of the Emergency Management Assistance Program, the 2007 program-led Review of the EMAP.

Key Informant Interviews: 31 interviews were conducted with EMAP Headquarters staff, AANDC Manitoba region staff, the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization and members of one First Nation community, and officials from Pubic Safety Canada. The purpose of these interviews was to gain a better understanding of effectiveness and efficiency of EMAP policies and procedures during the 2011-12 Manitoba flood.

Limitations

As described in the following section, the review was conducted over a relatively short period of time and toward the end of the fiscal year. This limited the ability of the review team to reach all the stakeholders involved - officials from the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters and the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs were not available to provide input into the study. Furthermore, the review team was only able to visit one First Nation community, although officials representing other communities were interviewed.

Mitigation Strategy for Limitations

Due to the limited input from First Nations and First Nation Organizations, the review team conducted an analysis of 103 media articles published by provincial and national papers. The articles were identified by searching AANDC Newsdesk archives that contained "Manitoba" and "flood" between January 2011 and February 2012, and analyzed for content related to the extent of flooding and the impacts on First Nations communities. Although this additional line of evidence filled a clear information gap, it was limited to information reported in newspapers and therefore, did not allow for an in depth exploration of each review issue from a First Nation perspective (i.e., it only partially addressed the limitation).

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Timing

The Terms of Reference for the review were developed with input from the AANDC Manitoba regional office, EMAP Headquarters, Public Safety Canada and the Provincial Emergency Measures Organization. They were then approved on February 16, 2012, by the AANDC Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive and presented to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on February 20, 2012, for their information and review.

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) was the project authority for this study and all the research was undertaken by the Branch, with input from the AANDC Risk Management and Assessment and Investigations Services branches. Research was carried out during February - March and involved two visits to Manitoba to collect data. During late March and early April, preliminary findings were presented to and validated by the AANDC Manitoba regional office and EMAP Headquarters, as well as officials from Public Safety Canada and the Provincial Emergency Measures Organization.

3 The 2011-12 Manitoba Flood: A Chronology from the Media

On December 23, 2011, Environment Canada announced that the year's biggest weather story was the historic flooding in the Prairies: 'We use that expression 'the flood of the century,' but … this could have been the flood of the millennium.'

Nine months earlier, in early March, the Government of Manitoba had announced that due to increased risks along the Assiniboine River, this year's flood could be on par with the flood of 2009. The 2009 flood had caused extensive damage, and both the province and the federal government were still dealing with its aftermath. Canada, for example, had just contributed $14 million to a $57 million fund to help affected property owners along the Red River and the Manitoba government was calling for a dedicated flood mitigation fund to reduce post-disaster funding pressures and Ottawa was open to discussing options.

By mid-April, the 2011 flood had surpassed expectations and was now being called the second worst flood in 150 years. Two flood related fatalities had been reported. Thirty local states of emergency had been called; all but three municipalities in the Interlake region had declared states of emergency or issued prevention orders. Fifty-two provincial and 650 municipal roads were closed, 1,100 people, 900 of them First Nations had been evacuated. The Premier of Manitoba called upon Canada to develop a national flood strategy to support Peguis and other First Nations now habitually hit by flooding.

By late April, the 2011 flood was being recognized as the worst in modern memory. Extensive overland flooding was still expected in the Interlake, an area subject to chronic flooding over the past few years. Water flow in Winnipeg was now higher than in 1950Footnote 5, 1979 and 1996. At this point, high numbers of evacuees were becoming a concern. By April 26, 1,954 people, the grand majority of them from the Peguis and Roseau River First Nations, had evacuated. Those from Roseau River First Nation were expected to be able to return home within days but the majority of those from Peguis First Nation were not expected to return for weeks.

On the last day of April, residents of Peguis, Roseau River and Lake St. Martin First Nations marched on AANDC's Winnipeg office protesting chronic flooding and the Government's response. Soon thereafter, officials from Lake St. Martin First Nation indicated they wanted to leave their community permanently because decades of flooding had resulted in a litany of health complaints, most from mould in houses. Later reports indicate dykes were being built around the community, as well as around the First Nations of Little Saskatchewan, Lake Manitoba and Sandy Bay, who were also badly affected by flooding.

Meanwhile, Manitoba farmers were being told that they could expect to be hit hard and that the flood damage fund for homeowners and cities would not be capped. The situation could be much worse, newspapers were reporting, if not for the province's three major flood mitigation structures (the Shellmouth dam and reservoir, Portage Diversion, and the Red River Floodway).

However, in early May, Manitoba's flood defences were reported as being threatened due to heavy spring storms and high winds. At the same time: the Prime Minister pledged to talk about mitigation during his tour of Manitoba; a faulty gauge on Saskatchewan's Qu'Appelle River was found to have been underestimating water flows to Manitoba; and 1,800 military had begun to arrive for what would prove to be an 18 day flood assistance mission. Lastly, Manitoba decided to create a breach in the Assiniboine dyke that would lead to the flooding of some lands but would reduce the risk of greater damage.

By mid-May, more than 3,600 people had been evacuated, most of them from First Nation communities (including Lake St. Martine First Nation), and most of these as a precaution against water washing over access roads. Manitoba released its Flood 2011 Building and Recovery Action Plan. The plan was expected to flow $70 million as quickly as possible into areas affected by the Assiniboine breach. On May 31st, mandatory evacuations were called for residents around Lake Manitoba and evacuees were told the evacuation might last into the fall. Property owners, including First Nations, launched protests in front of the Manitoba Parliament demanding action and questioning actions taken to date.

The Premier of Manitoba replied that Manitoba was doing all it could in the face of one of the worst storms in 350 years. In mid-July, residents from Dauphin River held a rally at the Provincial Legislature, and the Government of Manitoba presented a set of emergency drainage options invoking the construction of a $100 million 8 km drainage channel and a $60 million bypass channel around Lake St. Martin. By August, Manitoba began work on the $100 million channel -- considered to be amongst the largest emergency public works undertaken by the province. Construction was undertaken amidst debates from First Nations and others, about the channel's feasibility and necessity, the speed of start up, the potential impacts, and their frustration with the consultation process that had taken place. Later reports indicate that the channel was completed by late October.

By the last week of July 2011, estimated costs for fighting the flood had escalated to $750 million and wet and fallow fields were estimated to have cost the economy at least $1 billion. It was during this period that the newspaper began reporting on the situation of evacuees, a practice which has continued up to the spring of 2012.

In late November 2011, the Minister of Public Safety Canada announced a $50 million advance payment to Manitoba under the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements Program to Manitoba. It was also announced that the federal government had provided First Nations with $63.6 million in support and that the evacuations would cost at least $23 million. AANDC stated that the costs were unprecedented, but that '…our priority is the safety of First Nations so they (were) evacuated.' In all, 27 First Nations were affected, and as AANDC noted, unlike in previous years, the end was not in sight for many.

4 Review Findings - Relevance

4.1 Continuing need

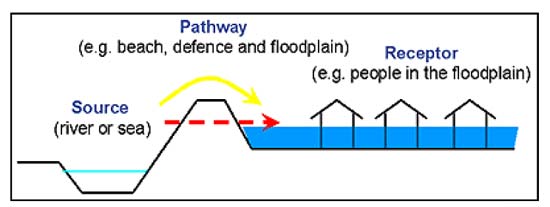

Risk is a difficult concept to define as it is used across a wide range of disciplines and activities. A common theme across all definitions is that it includes some elements of chance and the magnitude of potential loss (or consequences) and therefore, is commonly expressed as the product of probability and consequence: Risk = Probability * Consequence. However, in the case of flooding, risks can be further explained by applying a Source-Pathway- Receptor-Consequence modelFootnote 6 that accounts for:

- The nature and probability of the hazard (i.e., the source);

- The degree of exposure to the hazard (i.e., the pathway);

- The susceptibility of the people living in the floodplain (i.e., the receptor); and

- The value of receptor or the element at risk (i.e., the consequence).

Description of figure 2: Source-Pathway-Receptor-Consequence Model

Figure 2 illustrates a river which sits on the left of an embankment that prevents flood water from reaching houses to the right of the embankment. River is the source of the flood, which has to flow over the embankment (the pathway) to reach the houses which are the receptor.

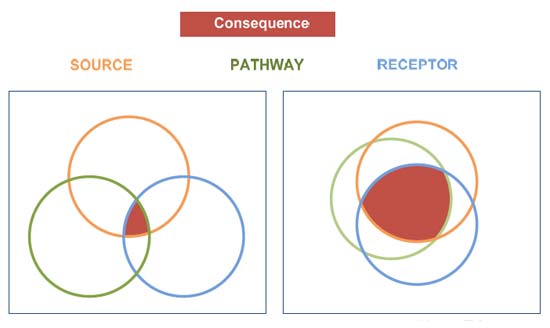

This model is useful for understanding flood risks because it clearly disaggregates the impact of flooding (i.e., the consequence) from the source (i.e., the hazard) and allows for a comprehensive analysis of how the interplay between the natural and social conditions that affect consequences. By way of example, Figure 3 (below) presents two Venn diagrams that illustrate how the consequences of a flood are determined by the relationship between the three other elements (source, pathway and receptor). The consequence (represented by the red polygon) is smaller in the image on the left compared to the image on the right because of the way in which the source, pathway and receptor intersect.

Description of figure 3: Source-Pathway-Receptor-Consequence Venn Diagram

Figure 3 displays two Venn diagrams - a diagram with three overlapping circles - that showing how the intersection of the source, pathway and receptor results in various sizes of consequence. The diagram contains a circle representing each of the source, pathway and receptor and where these circles overlap is shaded, which creates a triangular-like shape that represents the consequence. In the first diagram the intersection (the triangle) is quite small, representing a small consequence. In the second diagram there is more overlap between the circles, resulting in a larger consequence. This shows that consequence is dependent, as much on how the three variables interplay, as it is on the magnitude of any one variable.

Too often, emergency management is overly focussed on the source of flooding opposed the relationship between the source, pathway and receptor. In an attempt to avoid this pitfall, the remainder of this section explores the relevance of EMAP in the Manitoba flooding context based on the four components of the Source-Pathway- Receptor-Consequence model, which come together to determine the consequence of a given event.

Description of Flood Hazard

Southern Manitoba is characterized by two dominant river basins: the Red River and Assiniboine River. These two rivers meet at the city of Winnipeg and from there drain into Lake Winnipeg roughly 55 kilometres north of the city. The Red River basin drains roughly 287,500 km2, most of which is south of the Canada – USA boarder. The Assiniboine River, and its primary tributary – the Souris River, begin in Saskatchewan and drain roughly 182,000 km2.Footnote 7 These two basins act as a funnel, draining a vast area through a relatively small area.

These two river basins coupled with the Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg watersheds account for virtually the entire southern half of Manitoba. This whole area is largely composed of clay with characteristic low absorptive capacity. Furthermore, the slope of the terrain is characteristically gentle, averaging a drop of only 3-4 cm/km along the Red River Channel.Footnote 8 The flatness of the landscape is an observation that strikes nearly every visitor to southern Manitoba and it cannot be overstated. To add to the situation, the Red River floodplain has a number of natural levees, where the river channel is a higher elevation then the surrounding land. Once the riverbanks are overtopped, nothing holds back the water. For example, in 1997, the Red River spread to a width of about 40 km in southern Manitoba.Footnote 9

Given that both the Red and Assiniboine rivers drain such large basins (i.e., surface water from a large area of North America is funnelled through southern Manitoba) and the relative flatness of the landscape in southern Manitoba, flooding has been a fairly regular occurrence in Manitoba. Anecdotal evidence refers to larger floods in the late 1700s and early records show several major floods in the 1800s, the most notable being those of 1826, 1852 and 1861. This century, major floods occurred in 1950, 1966, 1979, 1996, 1997, 1999, and 2011 (refer to Appendix A for a detailed list of historical floods). It was widely reported at the time that the 1997 Red River flood was the "flood of the century", however, it was neither unprecedented nor unforeseen. As the 1997 International Red River Basin Task Force report, Red River Flooding: Short-Term Measures, concluded, "the flood of 1997 or an even larger one could happen any year".

However, predicting flooding remains a difficult task. It largely depends on (a) soil moisture at freeze-up time (i.e., the previous autumn); (b) total winter precipitation; (c) rate of snowmelt; (d) spring rain amount; and (e) a timing factor (i.e., timing of how the melt, spring precipitation come to together in relation to the orientation of the drainage basin).Footnote 10,Footnote 11

Although it is widely believed that climate change will result in a global increase in flood eventsFootnote 12,Footnote 13, climate models are less conclusive with respect to Manitoba's specific context. For example, Simonovic et al found that climate variability and change may cause an increase in annual discharge and shift ahead in flood starting time and peak occurrence time in both the Assiniboine and the Red River basins. The modeling did not show a significant difference in peak magnitude; however, it does show an increased frequency of large floods.Footnote 14

Description of First Nation Exposure to Flood Hazards

A pivotal event in Red River flood history was the 1950 flood, which was classified a great Canadian natural disaster based on the number of people evacuated and affected by the flood. This flood revealed the exposure of settlements along the flood plain in south-eastern Manitoba and the high costs associated with flood damages prompted all levels of government to search for ways to mitigate the flood hazard. By 1956, the provincial government established a Royal Commission to prepare a cost – benefit analysis for a range of flood protection schemes.Footnote 15 The Commission's report formed the basis for almost all the major flood works in the province, which include traditional structural approaches to limiting community exposure such as channel improvements, increased diking systems, detention reservoirs, and the diversion of floodwaters to protect specific areas. The comprehensive flood control system that was more or less an extensive plan to divert water around the city of Winnipeg.Footnote 16

Given that Winnipeg accounts for more than half of Manitoba's populationFootnote 17, this approach makes sense. However, these structures are of little value in protecting First Nations, in fact, some interviewees expressed concern that they may elevate the risk of flooding in First Nation communities. For example, the diversion of water through the Portage Diversion into Lake Manitoba has clearly increased water volume in Lake Manitoba and its outflow through the Fairford dam (and into Lake St. Martin). First Nation communities downstream of this dam were subject to extensive flooding during the 2011-12 event.

In summary, a community's degree of exposure to floods is determined by the pathway between the source (a river or a lake) and the community, and that many of Manitoba's First Nations are situated within a flood plain with little to no infrastructure to disrupt this pathway. Furthermore, infrastructure is expensive to build and maintain, and is most effective when combined with non-structural adjustments. For example, effective land use planning and deforestation both have an enormous potential to affect the flood pathway.

Description of First Nation Susceptibility to Flood Damage (i.e., the Receptor)

The concept of vulnerability in Canada and elsewhere has become an important component of, or new approach to, disaster studies. While initially focused on exposure-related variables, the notion of vulnerability has quickly expanded to include more social, economic, and political variables to explain disasters.Footnote 18 This corresponds with the Source-Pathway-Receptor-Consequence model by identifying the social, economic and political variables that affect the susceptibility of a community to the consequences of flooding.Footnote 19 By way of example, Wisner et al identify the following conceptual elements to categorize and analyze vulnerabilities:

Table 1: Key Determinants of Community Vulnerabilities

| Root causes | Dynamic Pressure | Unsafe condition |

|---|---|---|

Limited access to

|

Lack of

|

Local economy

|

Source: Abridged from "At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability and Disasters."Footnote 20

Recent research has identified a number of vulnerabilities that affect a First Nation's ability to cope with external stresses such as flooding. These include: dependence on social assistance, social problems (higher rates of alcoholism, drug abuse and violence), land use, and the quality and design of housing.Footnote 21 Interviews also reported concern with the ability of First Nations to cope with flooding given their limited financial and institutional capacities as well as a lack of a sense of ownership over community infrastructure. Without adequate capital to finance response and recovery, First Nations are left at the mercy of the disaster or forced to reach out to other levels of government for assistance. To further add to this, some stakeholders reported that unclear or weak governance structures within First Nations communities limit efficient and effective decision making, thus acting as barrier to coping with emergencies.

5 Review Findings - Performance

Emergency Management has been the subject of lengthy studies and discussions throughout North America and globally and, similarly, it is widely practiced. In an attempt to establish a common set of criteria for program development and implementation, standards associations (such as the International Organization for Standardization, the Canadian Standards Association and the National Fire Protection Association) began developing standards on emergency management programs in the 1990s. Although this review is not intended to assess the EMAP against these standards, it does incorporate the fundamental themes and components of these standards in order to establish a baseline of assumptions with respect to how an emergency management program should operate.

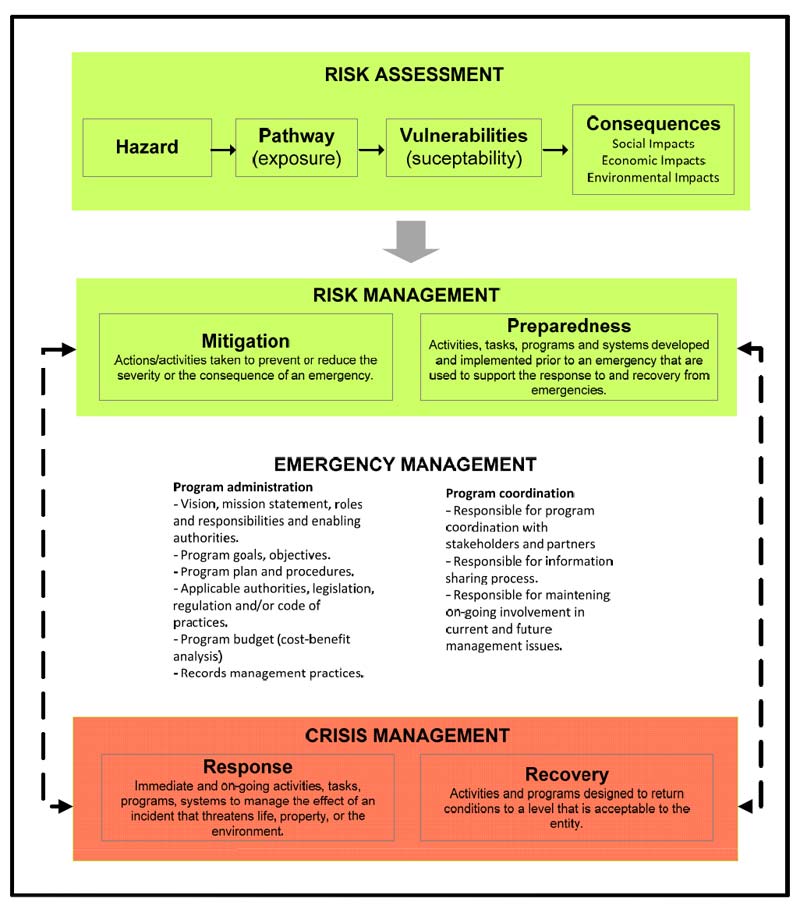

Although there are slight variations between the different standards, they generally contain the same themes. First, emergency management programs should be risk-based, that is, the program must identify the risk of emergencies (including the hazards and the vulnerabilities) that will form the basis by which the program is developed. The program then develops mitigation strategies to prevent or limit the consequences of an emergency (this is commonly referred as a risk mitigation strategy) and prepares for the residual risk (i.e., the risk that cannot be mitigated). Preparedness can include planning, developing partnerships for mutual aid or assistance, developing procedures, training etc. Once an event occurs, the program responds by taking immediate action to manage the effects of an incident and implements recovery strategies to return the entity to an acceptable state.

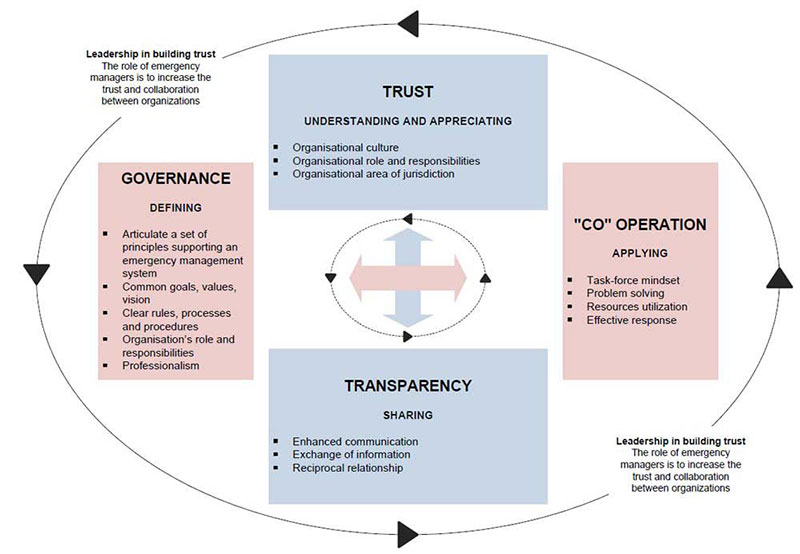

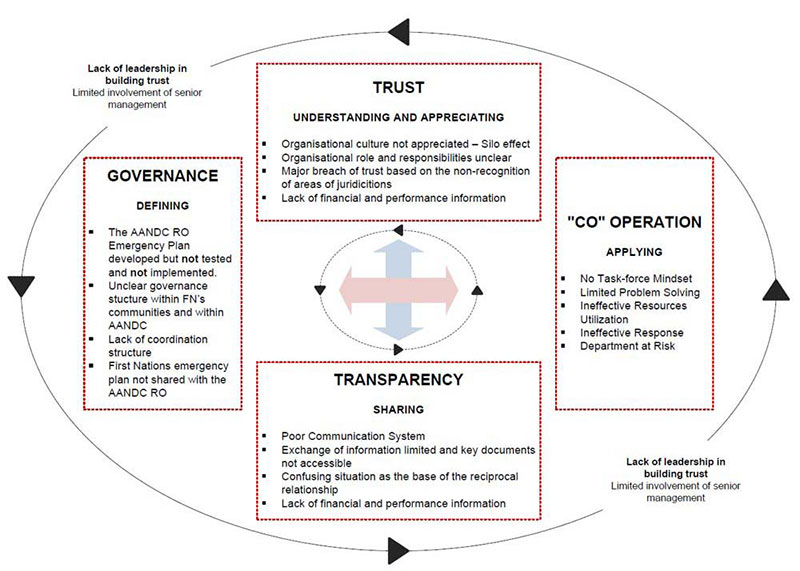

An emergency management program is, in essence, a balance between risk management (risk assessment, mitigation and preparedness) and crisis management (response and recovery). In this context, the review team developed the following conceptual framework to illustrate the relationship between these elements and an effective emergency management program:

Figure 4: Framework for Emergency Management

Source: Created by the Review Team based on the Emergency Management Act, the Federal Policy for Emergency Management (2009) and the NFPA 1600: Standard on Disaster/Emergency Management and Business Continuity Programs (2007).

Descritpion of figure 4: Framework for Emergency Management

Figure 4 displays a framework for emergency management. It shows how an emergency management program is, in essence, a balance between risk management (risk assessment, mitigation and preparedness) and crisis management (response and recovery). Typical emergency management programs first assess risks, which forms the basis by which the program is developed. Mitigation and preparedness strategies are then developed to limit the consequences of events and prepare to when the event actually happens. These two components represent risk management. Once an event occurs, the program responds by taking immediate action to manage the effects of an incident and implements recovery strategies to return the entity to an acceptable state. These two components represent crisis management. The emergency management program, which sits in between risk management and crisis management, focuses on administering its authority and achieving its objectives while coordinating with relevant stakeholders.

The remainder of this section explores the performance of EMAP during the 2011-12 Manitoba flooding, including how these concepts were applied by the program.

5.1 Effectiveness of emergency management during the 2011-12 Manitoba floods

Mitigation

All the key informants in this review reported that there were very few structural and non-structural mitigations measures in First Nation communities to limit the impacts of floods. Although other Canadian communities typically are designed to withstand a 100-year flood eventFootnote 22, there is limited evidence to suggest that the design of First Nation communities takes into consideration any level of flooding. This is supported by the fact that between 2006-07 and 2011-12, EMAP invested roughly $182,000 in mitigation in Manitoba, compared with $100,000,000 for preparedness, response and recovery.Footnote 23

Of course, there are exceptions to this situation, most notability, the ring dyke built around Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation in 1966 in response to the 1958 Manitoba Royal Commission on Flood Cost-Benefit.Footnote 24 Furthermore, the AANDC Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program reported that it supported four flood mitigation projects in Manitoba between 2006-07 and 2011-12 that totalled roughly $9.7 million. The focus of these projects was shoreline stabilization, home relocation and flood proofing in two First Nation communities. However, infrastructure investments related to mitigation are not currently coded per se and therefore, it is difficult to accurately determine if there were other expenditures. As such, these are the only examples of mitigation project in First Nation communities that the review found.

Although some program officials argued that community design is outside the scope of EMAP's terms and conditions, there are examples where an emergency management initiative can use recovery expenditures to influence community design. One such case is with the Public Safety Canada Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangement, which does not support costs of repairing or replacing structures if they are in a location that, prior to their construction, was recognized or zoned as a flood risk area by the municipal or provincial authorities. Furthermore, structures in place prior to a flood risk area designation are only eligible for assistance if they are not subsequently rebuilt within the designated flood risk area or adequate flood-proofing measures (placing structures behind levees, constructing them on stilts/columns or mounds) are taken to protect against the effects of a 100-year flood.Footnote 25

EMAP is simply not designed to influence long-term solutions to flooding in ways similar to the example above. Currently, the program funds communities to rebuild structures to pre-disaster conditions in accordance with what is eligible under the Public Safety Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangement. It does not, however, put conditions on the funding to prevent First Nations from rebuilding in the exact same flood risk area under the exact same flood protection despite repeated flood occurrences and relative certainty that flooding will recur. In fact interviewees reported that decisions related to rebuilding is entirely within the purview of the First Nation and that, if flood hazards are not considered at the community-level when rebuilding, AANDC could be left paying for response and recovery costs for the same homes multiple times (as opposed to addressing the root causes).

Despite this issue with EMAP's terms and conditions, the Manitoba regional office was able to leverage the flood response moneys in 2011-12 to create clay dykes in 13 communities that, if left in place, would protect the communities up to the water level experienced in 2011-12 on a permanent basis. Typically, EMAP will not support the construction of permanent structures such as clay dykes, however, it was determined that temporary sandbag dykes were not technically feasible given the volume and duration of the 2011-12 flood.

Recommendation #1: EMAP should develop better linkages with other programs within AANDC to ensure an effective system for supporting long-term solutions for emergency management and community resilience.

Preparedness

As part of the Department's preparedness, the AANDC Manitoba regional office developed an Emergency Management Plan in 2010 that is in line with the AANDC National Guidelines for Developing Regional Emergency Management Plans (2009). However, as discussed under Section 5.2, the plan was not fully implemented during the 2011-12 flooding, suggesting that the act of developing the plan did not adequately prepare the regional office for dealing with a large scale emergency. This could have potentially been avoided by effectively exercising the plan, but stakeholders reported that it was not tested prior to the flooding because Manitoba experiences flooding so frequently. Previous flood related emergencies were much smaller and simply did not prepare the office for the magnitude of flooding in 2011-12. In fact, the average annual expenditure on emergencies between 2006-07 and 2010-11 was roughly $5,000,000. Compared to this, the expenditures in 2011-12 were roughly 15 times this average annual expenditure.Footnote 26

Stakeholders reported that all 63 Manitoba First Nations had an emergency management plan in place prior to the flooding. Three example plans were made available for review and based on this limited sample, it is evident that the plans clarify the roles and responsibilities of Chief and Council as well as various community members (such as the coordinators of transportation, public works, education, etc) during emergencies. The plans clearly state that "the Chief and Council is the local authority responsible for the formation and implementation of emergency plans and arrangements for First Nations. According to the plans, the Chief must take what ever action he/she considers necessary to implement the emergency plan, (and) to protect the property, health safety and welfare of the community."Footnote 27 The plans also provide information on preparedness such as a hazards analysis and information on chemical hazards, flood preparation (for example, how to build sandbag dykes) and tornado preparation.

The regional office did not have copies of all the First Nation plans. Stakeholders also reported an overall lack of exercising or testing First Nation plans, as well as a lack of dedicated Emergency Management coordinators and unclear emergency management governance structures within First Nation communities. Stakeholders felt that this contributed to confusion as to how decisions were to be made in communities and created challenges for coordinating responses.

Recommendation #2: EIMD should develop guidelines for First Nation Emergency Management Plans that include protocols for how a First Nation can access assistance when their internal resources are overwhelmed. Once the guidelines are in place, the AANDC Manitoba regional office should work with First Nations to update their plans and maintain copies of the plans that will form the basis of future coordination work.

Finding #1: As of March 31, 2012, AANDC provided $84.5 million in support to 27 First Nation communities to respond to the flooding, but the effectiveness of the response is not known due to limited performance information.

During the winter of 2011, the Manitoba Water Stewardship Branch released several flood forecasts that raised concern about the potential for spring flooding throughout the province. In response to these forecasts, AANDC provided funding to the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters to help First Nations refresh community emergency management plans and attend a Disaster Management conference. The conference was held by the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization and included an extra day exclusively for First Nations to prepare for the forecasted flooding. Forty-nine First Nations attended the conference, which allowed communities to share information amongst each other and allowed the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters updated their contact list for community emergency management co-ordinators. With respect to updating the First Nation Emergency Management Plans, the regional office reported that 20 First Nations worked with the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters to refresh their plans, but that only seven provided the updated plans to the Association.

Once it became clear how specific communities were going to be affected, AANDC began providing First Nations, and in some cases, the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters on behalf of First Nations, with an "accountable advance" of funding for flood fighting activities. Twenty-seven First Nation communities received support from AANDC for flood fighting. For most communities this consisted of clearing drainage ditches, steaming culverts to eliminate ice blockages and building dykes to prevent over-land flow of water. Ultimately, 12 communities required evacuations and as of April 17, 2012, EMAP reported that 2445 people had not returned to their communities. The intent of AANDC support was to assist First Nations in reducing or eliminating the impacts of the flood on their health and safety and on the infrastructure of their communities.

EMAP clearly succeeded at protecting the immediate health and safety of First Nation communities.

With respect to protecting community infrastructure and long-term health and safety issues (such as the development of mould in houses that were flooded), success is much more difficult to assess. As noted above, EMAP support 27 First Nations to undertake activities required to prevent the floods from inundating their communities. The work plans under the funding agreements with First Nations typically included information on the number of sandbags required, the number of culverts that need to steamed, etc. They also provide a work break down that includes the number of people and hours of work required, as well as the rental or purchase of any equipment. The First Nations were responsible for spending the advance of eligible expenditures under the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization Disaster Financial Assistance Program and submitting the invoices and timesheets to that program, at which point, AANDC recovers the full amount of the accountable advanceFootnote 28. Where a First Nations was implementing a larger project, such as the construction of a permanent dyke, they were required to report to AANDC on progress against their work plan in the form of percentage complete for each task. The work plans did not reflect the First Nations' emergency management plans, nor did they require the First Nations to report on the effectiveness of their activities (i.e., the extent to which their activities reduced or eliminated the impacts of the flood on the health and safety as well as infrastructure of the community). This, coupled with a lack of participation by First Nations in this review, severely limited the review team's ability to assess the performance of AANDC's response.

In addition to providing financial support, the Emergency Management Coordinator was responsible for assisting First Nations with identifying required technical physical resources. This involved connecting First Nations, on an as-needed-basis, with the provincial government, the Manitoba Association of Native Firefighters, engineering or construction firms, heavy equipment, contractors, etc. Although this coordination function was a significant part of the Emergency Management Coordinator's role, some stakeholders reported that the Emergency Management Coordinator was effective at this role but that the 2011-12 flood was such a large emergency it was difficult to respond to all issues in a timely way.

Finding #2: Recovery is still ongoing, but stakeholders have concerns about the effectiveness of the current program mechanism.

According to the AANDC funding agreements, First Nations and the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters must submit a claim to the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization Disaster Financial Assistance Program. Funding agreements are very specific that AANDC funding is an accountable advance that can only be spent on eligible expenditures under the Provincial Program and that, once the province provides a payment for eligible costs, the full amount of the accountable advance will be recovered from the First Nation or the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters.

Stakeholders reported concern with the ability of the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization Disaster Financial Assistance Program to assist with recovery in First Nation communities. First, the program relies on community inspections that take time to complete. In many cases, First Nations will not begin re-construction until the program provides funding and this delay can lead to excessive damage (for example, not removing flooded drywall immediately can lead to large mould related issues) that leads to an increase in recovery costs.

The second issue identified was that the Provincial Program only allows recipients to re-build to a pre-existing state, that is to say that recipients are not allowed to improve the affected structures. In many cases, the structures on reserve prior to a flood were inadequate and therefore, re-building to the pre-existing state does not reduce vulnerability or mitigate risk.

The third issue raised was that the Provincial Program is designed to assist with recovery; the program is designed in a way that the victim carries a share of the burden. Two specific examples of this are that not all damage is eligible (First Nations reported that, for example, when a house is damaged, the drywall is eligible but the vapor barrier is not) and when a cost is eligible, the program pays the average price for the average quality of that product (i.e., it does not pay the replacement cost of the item). Although these examples may seem trivial, in some First Nation communities with very little financial capacity, it can mean the difference between re-building and not re-building.

5.2 Effectiveness and efficiency of the emergency management governance structure in Manitoba

Finding #3: The AANDC Manitoba Region Emergency Management Plan has established a governance and coordination structure; however, it was not implemented during the flooding.

AANDC Governance Structure

Within the AANDC Manitoba regional office, the Emergency Management Coordinator is responsible for gathering information and directing Manitoba regional operations for AANDC and the Funding Services Officer is responsible for acting as the primary point of contact for the First Nations. The Coordinator reports to the Director of Infrastructure and Housing, who is responsible for authorizing emergency expenditures. The Associate Regional Director General is responsible for maintaining contact with counterparts in the provincial government and escalating requests for assistance from other federal departments to AANDC HQ. Overall operations within the region and coordinating activities with other federal departments are the responsibilities of the Regional Director General. The Regional Director General reports to the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations, who provides executive support at AANDC HQ when the involvement of other government departments is required.Footnote 29

The Director of Infrastructure and Housing and Regional Director General are responsible for "authorizing expenditures within their authority and escalating requests for funding assistance requiring additional authority."Footnote 30 However, the Regional Plan is not designed to scale to the different sizes and severities of emergencies

The Manitoba Regional Office Emergency Management Plan also establishes a number of incident management system sections that report to the Emergency Management Coordinator. These include the following functions:

- An operations section responsible for: maintaining awareness of community-level activities, concerns, priorities and needs; preparing situation reports; and maintaining contact with operation centres in First Nations and other organizations.

- A planning section responsible for: documenting work plans; anticipating issues and working with stakeholders to develop plans; and maintaining contact with planning centres in First Nations and other organizations.

- A logistics section responsible for: indentifying resources that the regional office may provide in support of First Nations, scheduling and basic needs for staff working within the regional office; and maintaining contact with logistics centres in First Nations and other organizations.

- A communications section that is responsible for developing key messages in response to media and public inquiries.

- A liaison officer that would represent the regional office at other Emergency Coordination Centres to ensure an accurate and consistent exchange of information between agencies involved in a given emergency and to identify any concerns or opportunities for cooperation.

According to the Manitoba Regional Office Emergency Management Plan, these functions are to be implemented on an as required basis relative to the regional office level of response. A level one emergency is limited in geographic area, requiring no support to the First Nation. A level two emergency involves multiple communities with few or limited requests for operational assistance. This level of emergency involves a partial implementation of the incident command system depending on the scope, complexity or duration of the event. A level three emergency involves multiple communities requesting assistance. The flooding during 2011-12 clearly met the conditions of a level three emergency, which is the highest level of emergency identified in the plan. According to the plan, a response to a level three emergency involves full implementation of the incident command system due to the scope, complexity or duration of the emergency.Footnote 31

During the floods of 2011-12, there is no evidence that the regional office formally activated any of the incident management system, which meant that the Emergency Management Coordinator was largely responsible for fulfilling all the AANDC emergency management responsibilitiesFootnote 32 during the event (i.e., operations, planning, logistics, finance and administration and liaison).

Although regional staff reported that the response was a team effort and that everyone helped out where they could, the support was ad hoc and did not allow for the distribution of responsibilities away from the Emergency Management Coordinator as per the Manitoba Regional Office Emergency Management Plan. A few examples of such support are:

- In some cases funding services officers received information on the situation in communities. In cases where this happened, the information was shared with the Emergency Management Coordinator, but the funding services officers were not responsible for monitoring communities as stated in the AANDC Manitoba Region Emergency Management Plan.

- Additional resources were allocated to support the Emergency Management Coordinator to help provide HQ with required information to access supplemental funding. However, the Emergency Management Coordinator was the only person with a complete understanding of the situation and the required information and therefore, the assistance was limited to facilitating the process.

- The regional office invested a significant amount of effort to minimize disruptions in programs and services being delivered to First Nation communities. For example, the Education Program invested a significant amount of effort to help ensure evacuated children had the opportunity to attend alternative schools. The importance of this work cannot be understated, but it did not help fulfill AANDC's responsibilities for emergency management (rather it fulfilled AANDC's education responsibilities).

The fact that the incident management system was not activated exposed AANDC to significant level of risk. The emergency management system essentially depended on one person, which is unreasonable given the breadth of issues that arose during this emergency; the number of communities involved; and the 24-hour per day nature of the emergency. The result was that the Emergency Management Coordinator was on stand-by for 24 hours per day for months and essentially spent his time trying to address each crisis as they came up. The regional office does not compensate the Emergency Management Coordinator for acting as duty officer.Footnote 33 Moreover, although the regional office has identified a back-up Emergency Management Coordinator, this position was not drawn upon during the flooding.

Interview respondents from every stakeholder group identified this capacity issue as the key issue that needs to be resolved in the near future in order for the system to start functioning properly.

In an attempt to help minimize this risk, EMAP sent additional support (referred to as surge capacity) from HQ and other regions to Manitoba. These personnel served as liaison officers in the Provincial Emergency Coordination Centre, where they acted as a conduit between provincial officials and the AANDC Emergency Management Coordinator. They also helped prepare briefing materials for EMAP HQ on the situation. However, there were limitations in their support because they were not familiar with the provincial geography, agencies involved, and how the regional office functions.

Recommendation #3: EIMD and the AANDC Manitoba regional office should explore how to scale emergency management roles and responsibilities based on the size and magnitude of emergency events, including when and how HQ should become involved in decision making during a response.

Recommendation #4: The AANDC Manitoba regional office should develop the capacity to implement the full incident management system during future emergencies as stated in the AANDC Manitoba Regional Office Emergency Management Plan.

AANDC Coordination Structure

With respect to coordination, the regional office participated in a weekly conference call with the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization and other provincial representatives. This was lead by the Regional Director General and included representatives from the different areas in the regional office (e.g., Emergency Management and Infrastructure, Governance and Community Development, Programs and Partnerships, etc.). This call was essential for the Department to coordinate with the province on the various issues resulting from the flood.

From an operational perspective, the Manitoba Regional Office Emergency Management Plan establishes a coordination structure where the regional office is responsible for receiving requests for assistance from First Nations, assessing their requirements and coordinating the activities of other agencies involved with supporting First Nations. The Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization receives requests from the regional office.

Although the Regional Plan is clear on this structure, the National Emergency Management Plan is less clear. For example, under the Authorities and Legislative Requirements Section, the plan states that "the provinces and territories are responsible for activities related to emergency management within their respective jurisdictions." The National Plan goes on to identify a coordination structure that includes First Nations contacting provinces directly. It also states in the text that some of the Provincial Emergency Management Organizations have negotiated funding arrangements with AANDC for the provision of response functions to emergencies in First Nations communities, but does not clarify that First Nations in provinces that do not have a funding agreement should be contacting the AANDC regional office. In fact, the National Plan does not clarify the roles and responsibilities of a regional office where there is no funding agreement in anyway.Footnote 34 First Nations and other stakeholders reported confusion around this point.

According to the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization, this confusion resulted in several cases where First Nations contacted them directly. To address this, their standard protocol was to re-direct First Nations to the AANDC regional office. However, the province also reported that, with the volume of work during the flood, it was unreasonable to expect the Emergency Management Coordinator to respond to all requests in a timely way. It also reported that, in a few cases, because the time sensitive nature of emergencies, they were required to respond without input from AANDC. Although this was the exception and not the norm, it does present issues for the Manitoba Emergency Measures Organization because it is unclear whether their actions will meet the terms and conditions of AANDC's Emergency Management Assistance Program and therefore, be eligible for reimbursement.

Finding #4: The AANDC emergency management system relies on the experience and judgement of a few key people, with limited procedures, protocols or guidelines.

AANDC processes for supporting flood fighting