Archived - Impact Evaluation of the Labrador Innu Comprehensive Healing Strategy

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: December 7, 2009

(Project Number: 1570-7/08041)

PDF Version (588 Kb, 115 Pages)

Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

- 2.0 Methodology

- 3.0 Evaluation Findings

- 4.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

Acronyms

Executive Summary

Background

In November 2000, the leaders of the Sheshatshiu Innu and Mushuau Innu of Labrador asked the federal government and the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador to provide their communities with help to address a crisis of substance abuse and suicide occurring among children and youth. A number of meetings were held between the Labrador Innu leadership and the two levels of government to address the immediate, short, medium and long-term healing needs of the two communities. In response to these meetings, the federal and provincial governments made a series of commitments to the Labrador Innu to help heal their communities, including:

- Assessing the affected children and ensuring access to necessary treatment for gas sniffing addiction. [Note 1]

- Exploring long-term initiatives to support repair of the cultural and social fabric of both Innu communities.

- Registering the Innu of Labrador under the Indian Act [Note 2] and creating reserves for both communities.

- Continuing to implement the Mushuau Innu Relocation Agreement (MIRA), and covering the additional costs associated with housing in the new community of Natuashish.

These commitments, and others, formed the basis of the Labrador Innu Comprehensive Healing Strategy (LICHS). The commitments outlined above have since been implemented; the most concrete and measurable changes being the registration of both communities under the Indian Act and reserve creation, and the relocation of the Mushuau Innu from Davis Inlet to Natuashish in 2002, which allowed for the construction of a proper wharf and airstrip, clean water and indoor plumbing.

The ultimate goal of the strategy is to restore health and hope to the Innu communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu. It is designed to help resolve the serious health, social, safety and economic issues faced by the Labrador Innu, including: high rates of substance abuse, addiction, suicide, teen pregnancy, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), unemployment, and crime, as well as low levels of education, literacy and community-based capacity.

The objectives were to:

- Help ensure that Sheshatshiu and Natuashish are safe and secure;

- Improve the health and social conditions of the two communities;

- Increase the number of children and youth who attend school and graduate;

- Increase the job skills and economic opportunities for Innu First Nation members;

- Increase the ability of Innu to plan, deliver and manage programs and services, in a way that is culturally appropriate; and,

- Improve relations between the Innu of Labrador and the federal and provincial governments.

This evaluation was designed to assess relevance and performance; and more specifically to: (1) assess the effectiveness and impact of the LICHS; and (2) provide guidance and evidence‑based recommendations on future directions and next steps. Thus, this study sought to measure the degree to which the LICHS has improved the well-being of the Labrador Innu communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu; the effectiveness of the programming funded under the LICHS and identification of gaps; and the effectiveness of the integrated management approach used in LICHS to support Aboriginal healing initiatives.

Methodology

Evaluation methodology included:

- Preliminary Consultations (to inform the development of the evaluationmethodology);

- Document and File Review (including secondary research sources);

- Literature Review;

- Key Informant Interviews; and

- Community Case Studies (Interviews and Group Interviews).

Information used to inform the evaluation was gathered from multiple lines of evidence:

- Nine Preliminary consultations;

- Review of 249 files and documents;

- Review of 36 sources of literature;

- 27 Key informant interviews; and

- Two Community case studies with 56 interview participants (32 in Sheshatshiu and 24 in Natuashish).

Findings

Meanings of (community) healing

The findings suggest that healing is a long-term, ongoing, holistic and collaborative process. The key concern with respect to the application of healing principles is how the federal partners operationalize the concept of "community healing" and about whether the comprehensive nature and scope of healing is actually reflected in the funded healing initiatives. This implementation approach is often not reflective of Innu concepts of healing. Some key informants suggested that an Innu definition of community healing must guide LICHS efforts.

Relevance

Key informant interviews, case study interviews, and documents reviewed suggest that at a minimum there is a need for continued and long-term, government support for healing. While interviews and reviewed statistics seem to suggest that the Labrador Innu communities have begun the complex process of healing (e.g., improvements in capacity levels and infrastructure), there are still significant gaps between the Innu and their First Nation counterparts, particularly with respect to education and health. While some gaps have narrowed, particular needs with respect to health, education, and infrastructure (and housing in Sheshatshiu) are readily apparent. Statistics available, as well as interviews and documents reviewed, suggest significant support is still required, and there are numerous unmet needs that need to be addressed.

While in line with the Government of Canada, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Health Canada (HC) priorities, there are concerns that the LICHS is not 'comprehensive'; that much of its programming is disjointed; that it is limited in its depth and/or breadth; lacks a long‑term strategic plan; and that it contains no built-in provisions/flexibility to respond to evolving Innu needs.

Implementation and Delivery

In the last five years, LICHS partners (HC, INAC and Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation have funded a number of program activities that support the continued healing needs of the Innu, including: infrastructure development (e.g., Safe Houses in both communities); Strategies for Learning (geared toward improving the educational attendance, achievement and ability of Innu children); implementation and/or continued delivery of addictions and mental health programs, maternal and child health programs, as well as healing staff capacity building initiatives delivered by the Labrador Health Secretariat (LHS); and the creation and staffing of an Integrated Management position. These achievements are, however, tempered by a number of existing challenges such as infrastructure limitations (e.g., lack of space, privacy, confidentiality), which affect the ability of front-line staff to deliver effective community-based programming; high rates of staff turnover that negatively impacts on the levels of communication and trust between the strategy partners, as well as resulting in the constant loss of corporate knowledge; and, limited performance measurements, which act as a barrier to effectively assessing the progress toward objectives. A further challenge to the implementation and delivery of LICHS programs and services, discussed by key informants and community interview participants, involves the LHS mandate and the office policies and procedures, as well as the rationale for having the office located in Goose Bay, rather than the communities.

Success

This evaluation revealed evidence of some successes and challenges in the Innu healing process with respect to the four primary strategy objective areas: health, social programs and education; capacity development; integration, coordination and partnerships; and community infrastructure.

A wide range of successes were noted, including:

- marked reduction in completed suicides;

- increased awareness of healthy behaviours (e.g., exercise);

- increased awareness of the relationship between FASD and alcohol consumption;

- availability of culturally appropriate healing programs;

- positive outcomes associated with treatment and health programs (e.g., decrease in alcohol and/or drug use by participants, enhanced self-esteem, increase in breastfeeding; increased awareness of Innu cultural practices);

- improvements in educational attendance and achievement by primary school children in Natuashish;

- progress toward the implementation of specific Philpott recommendations;

- devolution of education;

- stronger and more focused leadership with improvements in capacity;

- increased program staff capacity due in part to initiatives and support offered by LHS staff;

- improved relations at the Main Table;

- strong informal healing program partnerships at the community level;

- construction of the Healing Lodge and the Wellness Centre in Natuashish;

- design and construction of the new school in Sheshatshiu; and

- construction and staffing of Safe Houses in both communities.

The strategy has also experienced a number of challenges, including:

- ongoing concern with substance abuse issues in both communities;

- lack of adequate healing infrastructure in Sheshatshiu;

- limited academic improvements in the upper level grades in Natuashish;

- limited Innu involvement in planning and decision making; and

- inadequacy of resources associated with the LICHS.

Cost-Effectiveness and Alternatives

Attribution of intended outcomes of funds from LICHS is difficult given the limited outcome measures and multiple interventions, both within and exterior to LICHS, intended to improve conditions for the Labrador Innu. Additionally, the absence of a needs assessment makes it difficult to comment on the degree to which LICHS funds were actually spent addressing community needs. Some research does indicate, however, that community interventions such as these are more cost-effective than non-community-based alternatives. Interviewees provided a variety of options for making the LICHS more cost-effective.

Future Considerations

Progress made under the LICHS is considered sustainable beyond 2010 but only with continued support and guidance from the federal government. Although the Labrador Innu communities are still described as being at risk of returning to a state of crisis without continued support for healing and community development, there is a sense that positive momentum has begun to build in the communities.

Recommendations

The evaluation found strong evidence of a need for long-term, government supported Innu healing in order to address unresolved social, health, safety and economic issues, and to maintain and build upon healing progress that has already occurred in the two Labrador Innu communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu.

1. In order to sustain and move forward on the progress made through this strategy, additional support to the Labrador Innu communities will be required.

2. In order to sustain and move forward on the progress made through this strategy, additional support for community-based healing programs, services and events in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu will be required.

Should the strategy continue, the following recommendations are suggested for improving its effectiveness and impacts:

To incorporate an Innu perspective, a process should be put in place to reach a mutual understanding and agreement on what approach should be developed and what activities should be included as healing initiatives.

3. The Innu and the federal government need to engage in a facilitated process whereby both can mutually develop the key terms and definitions, and then respectively share them in an open and constructive dialogue to reach a mutually agreed upon approach to healing for future activities.

- An Innu worldview/perspective should be incorporated into the strategy and clearly reflected in key healing definitions and related activities. These should inform and influence the design, delivery and implementation of the new phase of the strategy.

To ensure that the strategy continues based truly on Innu healing needs, and is comprehensive and flexible enough to respond to evolving Innu needs.

4. Implement a healing needs assessment in the two communities to better understand ongoing and unmet needs. This should include an evaluation matrix, and a Performance Measurement Strategy. The findings generated from the needs assessment and associated documents should be presented to the Main Table.

5. Based upon the evidence presented and input provided by the Innu, a determination should be made by all partners as to how existing programs and services might be appropriately adjusted, including exploring possible alternatives to existing funding authority arrangements, but remaining consistent with departmental commitments to support Labrador Innu healing. The findings and resulting determinations should be used to guide the new phase of the strategy.

To ensure that the next phase of the strategy is community-based and supportive of Innu capacity and self-government.

6. The federal government needs to continue to play a substantial role in supporting Innu capacity and self-government. It also needs to provide the resources necessary to implement the training and capacity building activities required, within current authorities and consistent with departmental commitments to support Innu capacity and self-government, and to build the skills and abilities of the Innu, on terms agreed to by the parties in the new phase of the strategy.

7. The parties need to mutually develop an Agreement regarding how accountability and transparency will be maintained.

8. The Main Table and its subcommittees will continue with more active Innu engagement and develop a means for outreach to the communities at large, to encourage broader participation by community members in healing.

9. Government and Innu engage in a process to agree together how best to realign resources currently allocated to the LHS in Goose Bay so that the funds flow directly to the communities and utilize Innu expertise to the extent possible. The overarching rationale is to better serve the community according to their identified needs.

To provide a solid evidence base for the ongoing healing of the communities and to track changing healing needs and accomplishments.

10. The parties need to develop a tripartite committee tasked with reviewing and providing feedback to the main partners on any existing and future evaluation and monitoring plans; including developing specific action items and timelines; and with the end objective to have solid evidence to monitor progress, with evaluation and monitoring data owned by the Innu, with continued support from partners.

Management Response and Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager | Planned Implementation Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. In order to sustain and move forward on the progress made through this strategy, additional support to the Labrador Innu communities will be required. | INAC will contribute to the Labrador Innu efforts in building healthy, sustainable and resilient communities by stabilizing funding for on-reserve programs and services equivalent to that provided to other First Nations. | 1. Atlantic Region, INAC | September 2010 |

| Health Canada will contribute to Innu community-based healing goals by supporting community healing programs in the areas of mental health and maternal child health. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic Region, Health Canada | April 2010 | |

| 2. In order to sustain and move forward on the progress made through this strategy, additional support for community-based healing programs, services and events in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu will be required. | INAC will provide resources to the Innu in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu for on-reserve programs and services, and the Innu will have access to proposal-based program funding available to all First Nations. | 1. Atlantic Region, INAC | September 2010 |

| Health Canada will continue to provide support to the Innu in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu for community-based healing programs, services and events. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic Region, Health Canada | April 2010 | |

3. The Innu and the federal government need to engage in a facilitated process whereby both can mutually develop the key terms and definitions and then respectively share them in an open and constructive dialogue to reach a mutually agreed upon approach to healing for future activities.

|

INAC will continue participating in open and constructive dialogue with the Innu and other federal and provincial partners though the existing tripartite mechanisms to contribute to building healthy, sustainable and resilient communities. | 1. Treaties and Aboriginal Government, Social Policy and Programs, Atlantic Region, INAC | April 2010 |

| Existing tripartite mechanisms will be used by HC to develop a shared understanding of key terms and definitions such as 'healing', 'capacity' and 'capacity building' in the context of moving forward. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic Region, Health Canada | March 2011 | |

| 4. Implement a healing needs assessment in the two communities to better understand ongoing and unmet needs. This should include an evaluation matrix, and a Performance Measurement Strategy. The findings generated from the needs assessment and associated documents should be presented to the Main Table. | INAC will continue participating in the open and constructive dialogue with the Innu and other federal and provincial partners to support community-wide Innu goals to build resilient and sustainable communities by participating in the Main Table. | 1. Atlantic Region, Social Policy and Programs, INAC | April 2010 |

| Pending renewal of the strategy, HC, in partnership with the Mushuau and Sheshatshiu Innu and other stakeholders, will support a healing needs assessment that will inform the next phase of healing. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | March 2011 | |

| 5. Based upon the evidence presented and input provided by the Innu, a determination should be made by all partners as to how existing programs and services might be appropriately adjusted, including exploring possible alternatives to existing funding authority arrangements, but remaining consistent with departmental commitments to support Labrador Innu healing. The findings and resulting determinations should be used to guide the new phase of the strategy. | INAC and other federal departments have a range of proposal-based programs that could support the Innu priorities. INAC will provide information and assist the Innu to submit proposals to access this potential programming. | 1. Atlantic Region, INAC | April 2010 |

| Health Canada will work with the Innu to determine how existing community health programs might be adjusted to better align with Innu healing priorities. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | June 2011 | |

| 6. The federal government needs to continue to play a substantial role in supporting Innu capacity and self-government. It also needs to provide the resources necessary to implement the training and capacity building activities required, within current authorities and consistent with departmental commitments to support Innu capacity and self-government, and to build the skills and abilities of the Innu, on terms agreed to by the parties in the new phase of the strategy. | Within current authorities and consistent with departmental commitments, INAC will support Innu capacity and self-government by facilitating application to and the effective use of INAC proposal-based program funding available to support these goals. | 1. Atlantic Region, INAC | March 2011 |

| Within existing resources, Health Canada will continue to support Innu capacity for health program delivery. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | April 2010 | |

| 7. The parties need to mutually develop an Agreement regarding how accountability and transparency will be maintained. | INAC will assist the Innu to access the proposal-driven programs which provide support for governance capacity building and could facilitate additional work in developing accountability and transparency practices required to meet the terms and conditions of program and service funding. | 1. Atlantic Region, INAC | TBD |

| Within existing authorities and resources, HC will work with the Innu and other stakeholders in developing accountability and transparency practices required to meet the terms and conditions of program and service funding. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | March 2011 | |

| 8. The Main Table and its subcommittees will continue with more active Innu engagement and develop a means for outreach to the communities at large, to encourage broader participation by community members in healing. | INAC's ongoing participation in the existing tripartite mechanisms, including the work of the Main Table, will support the Innu efforts to engage broader community membership in building resilient and sustainable communities. |

1. Regional Director, FNIH Atlantic Region, Health Canada

2. Treaties and Aboriginal Government, Social Policy and Programs, Atlantic Region, INAC |

September 2011 |

| Health Canada's ongoing participation in existing tripartite mechanisms, such as the Main Table, will support Innu capacity to engage broader community membership in building resilient and sustainable communities. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | March 2011 | |

| 9. Health Canada: Government and Innu engage in a process to agree together how best to realign resources currently allocated to the LHS in Goose Bay so that the funds flow directly to the communities and utilize Innu expertise to the extent possible. The overarching rationale is to better serve the communities according to their identified needs. | Health Canada will continue to contribute to Innu community-based healing goals by supporting a range of community health programs in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | June 2011 |

| 10. The parties need to develop a tripartite committee tasked with reviewing and providing feedback to the main partners on any existing and future evaluation and monitoring plans; including developing specific action items and timelines; and with the end objective to have solid evidence to monitor progress, with evaluation and monitoring data owned by the Innu, with continued support from partners. | INAC will support the Innu in taking greater ownership of the entire cycle of the performance measurement strategy including needs assessment, management of community programs and monitoring of performance and outcomes, through regularizing funding for on-reserve programs and services and through facilitating access to proposal-based program funding to develop capacity. | 1. Atlantic Region, INAC | September 2010 |

| Health Canada will continue to provide support to the Innu in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu for community-based healing programs, services and events. | RD, FNIH, Atlantic region, Health Canada | June 2011 |

1.0 Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

1.1 Purpose and Structure of the Report

The report contained herein outlines the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the impact evaluation of the Labrador Innu Comprehensive Healing Strategy (LICHS). The period of study for this report is 2004/05 to 2009/10. This report provides a synthesis and analysis of all the data collected from the various lines of evidence described in Section 2.

This report is structured as follows:

- Section 1: Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

- Section 2: Methodology

-

Section 3: LICHS Findings

- Relevance

- Implementation and Delivery

- Success

- Cost Effectiveness

- Future Considerations

-

Section 4: Conclusions and Recommendations

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

1.2 Objectives of the Evaluation

The overarching intent of this evaluation was to fulfill a Treasury Board requirement to provide support for accountability to Parliament and Canadians; inform government decisions on resource allocation and reallocation related to LICHS; and inform Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Health Canada (HC) as to whether the LICHS is producing the outcomes it was designed to produce. More specifically, this evaluation was designed to: (1) assess the effectiveness and impact of the LICHS; and (2) provide guidance and evidence-based recommendations on future directions and next steps. Thus, this study sought to measure the degree to which the LICHS has improved the well-being of the Labrador Innu communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu; the effectiveness of the programming funded under the LICHS and identification of gaps; and the effectiveness of the integrated management approach used in LICHS to support Aboriginal healing initiatives.

The evaluation findings are organized into the following key issues:

- Relevance

- Implementation and delivery

- Success

- Cost effectiveness

- Future Considerations

1.3 Scope

The evaluation focused on the effectiveness of programming funded under the LICHS from 2004/05 to 2009/10. Due to timelines required for reporting back to Treasury Board, data for the fiscal year 2009/10 will be incomplete.

1.4 Context and Background of the LICHS

It is only recently that the Innu parted from their traditional, nomadic way of life, adopting sedentary living and participating in the wage economy. In fact, it has been less than 40 years (1971) since the last group of nomadic Innu was settled in permanent communities and only 42 years since the Mushuau Innu were relocated to Davis Inlet. Many Innu have been living for 30 to 40 years, or more, with the trauma associated with relocation and the process of social and cultural disintegration – the loss of their social, cultural, environmental, and spiritual identity. In addition, many Innu continue to deal with the legacy of generations of substance abuse as well as sexual, physical and emotional abuse.

In the 1990's the media brought the plight of Innu children to national and international attention [Note 3] [Note 4]. In a report produced by Survival International [Note 5], it was stated that the plight of the Innu was the worst the organisation had seen anywhere, with the highest suicide rate in the world. Additionally, infant and child mortality statistics cited in the report revealed that an Innu child from Sheshatshiu (1983-94 statistics) was three times more likely to die before the age of five than the average Canadian child; and a child from Utshimassits (also known as Davis Inlet, which had no sewage or household running water and only airplane access to the nearest hospital) was seven times more likely to die before the age of five than the average Canadian child (1984-94 statistics). It was also noted in the report that between 1990 and 1998, there had been eight completed suicides; equivalent to a rate of 178 per 100,000, compared to the Canadian rate at the time of 14 per 100,000.

According to Band Council records, at least one-third of adults had attempted suicide. For Mushuau Innu, excessive rates of alcoholism (80-85 percent) were reported to be ravaging community members over the age of 15 years, and 100 percent of Mushuau Innu children over the age of six years were sniffing gas and about 30 percent of those were chronic users. [Note 6]

In November 2000, the leaders of the Sheshatshiu Innu and Mushuau Innu of Labrador asked the federal government and the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) to provide their communities with help to address a crisis of substance abuse and suicide occurring among children and youth. A number of meetings were held between the Labrador Innu leadership and the two levels of government to address the immediate, short, medium and long-term healing needs of the two communities. In response to these meetings, the federal and provincial governments made a series of commitments to the Labrador Innu to help heal their communities, including:

- Assessing the affected children and ensuring access to necessary treatment for gas‑sniffing addiction [Note 7].

- Exploring long-term initiatives to support repair of the cultural and social fabric of both Innu communities.

- Registering the Innu of Labrador under the Indian Act [Note 8] and creating reserves for both communities.

- Continuing to implement the Mushuau Innu Relocation Agreement (MIRA), and covering the additional costs associated with housing in the new community of Natuashish.

These commitments, and others, formed the basis of the LICHS. The commitments outlined above have since been implemented; the most concrete and measurable changes being the provision of addictions treatment services to Innu children, the registration of both communities under the Indian Act and reserve creation, and the relocation of the Mushuau Innu from Davis Inlet to Natuashish in 2002, which allowed for the construction of a proper wharf and airstrip, clean water and indoor plumbing.

The Healing Strategy, which first received federal approval in June 2001, included representatives from: INAC; HC; Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC); the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP); and the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The current iteration of the strategy includes representation from: INAC; HC; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) as funded partners. The Province of Newfoundland and Labrador still has a role to play, especially in the area of service delivery. The Mushuau and Sheshatshiu Innu participate in the management of the Healing Strategy through their involvement in the Main Table.

The ultimate goal of the strategy is to restore health and hope to the Innu communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu. It is designed to help resolve the serious health, social, safety and economic issues faced by the Labrador Innu, including: high rates of substance abuse, addiction, suicide, teen pregnancy, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), unemployment, and crime, as well as low levels of education, literacy and community-based capacity.

The objectives articulated were to:

- Help ensure that Sheshatshiu and Natuashish are safe and secure;

- Improve the health and social conditions of the two communities;

- Increase the number of children and youth who attend school and graduate;

- Increase the job skills and economic opportunities for Innu First Nation members;

- Increase the ability of Innu to plan, deliver and manage programs and services, in a way that is culturally appropriate; and,

- Improve relations between the Innu of Labrador and the federal and provincial governments.

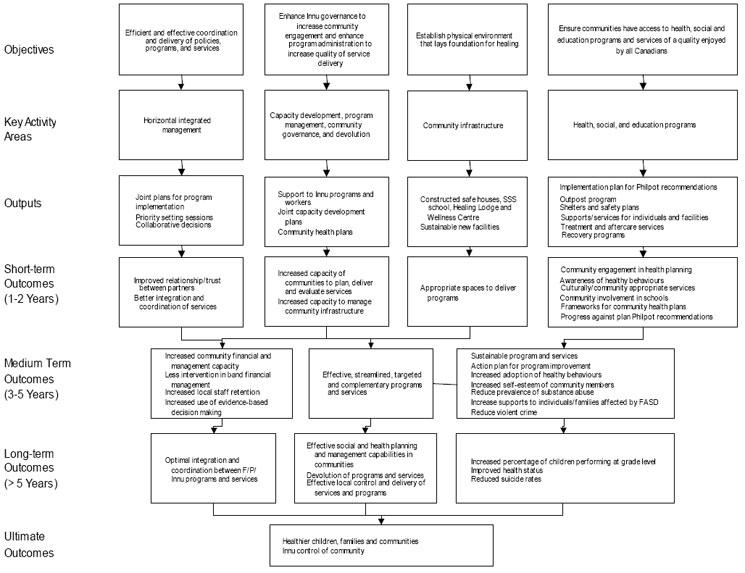

The logic model developed for the 2007 Results-Based Management Accountability Framework (RMAF) [Note 9] is shown in Figure 1 (Section 2.2). The overarching objectives stated in the logic model are more specific to the implementation of the strategy; however the objectives as stated in the 2005 Treasury Board submission are reflected in the stated outcomes of the logic model. However, the differences and variations are significant enough to shift focus with respect to measurement. Despite the fact that the RMAF and accompanying logic model were designed in 2007, the purpose of these tools is to guide the implementation of the LICHS. Consequently, the objectives stated in the logic model will be the objectives used throughout this evaluation with the caveat that much of the strategy had been designed and at least partially implemented before these objectives were articulated in an RMAF. As a result, some activities and outputs may not directly support the articulated outcomes.

A vision for the strategy further organizes the objectives into the following four activity areas:

- Capacity development, program management, community governance and devolution: build Innu capacity with respect to governance, administration, management and devolution.

- Community infrastructure: improve the physical environment of the Innu communities.

- Health and social programs and education: improve the health, social well-being and education levels of Innu.

- Horizontal integrated management: enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the delivery of the strategy through improved coordination of policies, programs and service delivery.

The Healing Strategy was initially funded from 2001/02 to 2003/04, with the federal government providing $81 million over three years. The first phase focused on five main program components: community health programming (including addressing the gas sniffing crisis and establishing the Labrador Health Secretariat (LHS), a HC office in Goose Bay to support the implementation of the LICHS; Mushuau Innu relocation; registration and reserve creation; programs and services (those available on all reserves across Canada); and community policing. While some progress was achieved during the first three years, an interim evaluation concluded that insufficient effort was made during the first phase to involve the Innu in the planning and development of the strategy, and that more collaboration was required as the strategy moved forward.

The LICHS was bridged for a one-year period, from 2004 to 2005, and an additional $20.5 million was provided to ensure the continuation of the programs and services funded under the strategy (refer to Table 1).

A policy proposal put forward in December 2004 recommended that the LICHS be continued and funding was requested for INAC, HC and PSEPC. While approved, funding in the reduced amount of $102.5 million was awarded for the period 2005/06 to 2009/10 to INAC and HC only (refer to Table 2 for a breakdown of allotted funds).

| Budget | Actual | |

|---|---|---|

| INAC 2004-2005 | ||

| Education | $3,354,320.00 | $8,600,000 |

| Child, Youth & Family Services | $5,570,801.00 | |

| Income Support | $703,602.00 | |

| Facilities Operations and Maintenance (O&M) (Natuashish) | $4,133,138.00 | $4,100,000 |

| Reserve Creation | $192,500.00 | $192,500 |

| Devolution Tables | $484,899.00 | $484,899 |

| New Paths (Outpost) | $200,000.00 | $200,000 |

| Strategies for Learning | $67,000.00 | |

| Main Table | $93,740.00 | $93,740 |

| Total INAC | 14,800,000.00 | $13,670,139 |

| Health Canada 2004-2005 | ||

| Addictions/Mental Health | $2,975,035.00 | |

| Public Health | $1,031,630.00 | |

| Community Health Planning | $666,790.00 | |

| Labrador Health Secretariat | $826,545.00 | |

| Total Health Canada | $5,500,000.00 | $4,800,000 |

| RCMP 2004-2005 | ||

| Sheshatshiu Police Detachment | $200,000.00 | |

| Total CMHC | $200,000.00 | |

| Total Submissions | $20,500,000.00 | |

Expenditure data shows that the majority of INAC funding received and spent under the strategy was for A-Base services [Note 10]. Only about 20 percent of the funds allocated were for enhanced healing programs and services. It is also important to note that actual expenditures for A-Base programs and services were far more than estimated figures, nearly doubling budgeted amounts by the end of the fourth year. Additionally, the proportion of funding directed to healing-specific initiatives relative to A-Base programs and services has decreased steadily over time. By year four, INAC funds dedicated to healing fell to around 10 percent of its actual expenditures. Funds for the LICHS, while targeted, were delivered through existing authorities making it difficult to track LICHS-specific expenditures and to respond to the changing needs of the Innu (given the limitations of both policy and existing terms and conditions).

The key initiatives that fall within the four activity areas listed above include: additional funding for A-Base and A-Base like programs; safe house construction in both communities intended for women and children at risk; design and construction of a new school in Sheshatshiu; a Healing Lodge and Wellness Centre in Natuashish; reserve creation; capacity development; community health; and integrated management (e.g., Main Table, Director of Integrated Management position).

All partners involved in the current phase of the strategy (INAC, HC, CMHC [Note 11], Labrador Innu, Province of NL) are responsible for ensuring that the Healing Strategy enhances individual, family, community and government resources for healing and for ensuring the sustainability of these resources.

Although the evaluation is only intended to focus on the last five years of LICHS, it is important to consider the historic and current context in order to adequately understand and assess the issues and the outcomes of the strategy. It is also important to note that the issues that the LICHS has been tasked to address are long-standing, complex and devastating to the Innu who had little, if any knowledge, of such problems (e.g., addiction, abuse, suicide) prior to settling in communities [Note 12] [Note 13].

| Source: INAC. (2009). Annex A: LICHS Program Elements: LICHS Budget Received by Region. INAC Regional Office, Amherst, N.S. | |||||||

| INAC | FTEs | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheshatshiu School Design | $100,000 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $100,000 | |

| Education | $2,262,600 | $2,340,000 | $3,075,000 | $3,485,000 | $3,635,000 | 14,797,600 | |

| Child, Youth & Family Services | $5,570,800 | $5,571,000 | $5,571,000 | $5,571,000 | $5,571,000 | $27,854,800 | |

| Income Support | $438,100 | $1,308 000 | $1,358 000 | $1,508,000 | $1,508,000 | $6,120,100 | |

| Electrification - Natuashish | $2,000,000 | $1,000, 000 | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | $6,000,000 | |

| Airport Agreement - Natuashish | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $500,000 | |

| A-Base/A-Base Like | $10,471,500 | $10,319,000 | $11,104,000 | $11,664,000 | $11,814,000 | $55,372,500 | |

| Facilities O&M Capacity Building | $900,000 | $900,000 | $750,000 | $600,000 | $450,000 | $3,600,000 | |

| Housing Capacity Building | $295,000 | $245,000 | $60,000 | $0 | $0 | $600,000 | |

| LTS Capacity Building | $420,000 | $420, 000 | $320,000 | $120,000 | $120,000 | $1,400,000 | |

| Reserve Creation | $220,000 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $220,000 | |

| Devolution Planning and Transition | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $750,000 | |

| New Paths (Outpost) | $200,000 | $200,000 | $200,000 | $200,000 | $200,000 | $1,000,000 | |

| Strategies for Learning | $555,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $2,155,000 | |

| Planning and Consultation | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $500,000 | |

| Safehouses | $100,000 | $100,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $1,400 000 | |

| Healing | $2,940 000 | $2,515,000 | $2,380,000 | $1,970,000 | $1,820,000 | $11,625,000 | |

| Sub-total INAC Grants & Contributions | $13,411 500 | $12,834,000 | $13,484,000 | $13,634,000 | $13,634,000 | $66,997,500 | |

| Salaries | 9.0 | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 | $2,700,009 |

| EBP | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 | $540,000 | |

| Accommodations | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 | $351,000 | |

| Housing Capacity Building | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $750,000 | |

| Planning and Consultation (CFN) | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $750,000 | |

| Legal Agent for reserve creation | $50,000 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $50,000 | |

| Departmental Operations | $520,300 | $347,800 | $347,800 | $347,800 | $347,800 | $1,911,500 | |

| Sub-total INAC Integrated Management | 9.0 | $1,588,500 | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 | $7,052,509 |

| Total INAC | 9.0 | $15,000,000 | $14,200,000 | $14,850,000 | $15,000,000 | $15,000,000 | $74,050,009 |

| Health Canada | FTEs | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | Total |

| Addictions/Mental Health | $2,411,000 | $2,520,000 | $2,550,000 | $2,550,000 | $2,550,000 | $12,581,000 | |

| Mental/Child Health | $705,000 | $630,000 | $655,000 | $655,000 | $655,000 | $3,300,000 | |

| Community Health Planning | $225,000 | $200,000 | $225,000 | $225,000 | $225,000 | $1,100,000 | |

| Management and Support | $175,000 | $125,000 | $95,000 | $95,000 | $95,000 | $585,000 | |

| Sub-total HC Grants & Contributions | $3,516,000 | $3,475,000 | $3,525,000 | $3,525,000 | $3,525,000 | $17,566,000 | |

| Salaries | 20.0 | $1,056,700 | $1 056,700 | $1,056,700 | $1,056,700 | $1,056,700 | $5,283,520 |

| EBP | $211,300 | $211,300 | $211,300 | $211,300 | $211,300 | $1,056,500 | |

| Other Operating | $578,600 | $619,600 | $569,600 | $569,600 | $569,600 | $2,907,000 | |

| Sub-total HC Integrated Management | 20.0 | $1,846,600 | $1,887,600 | $1,837,600 | $1,837,600 | $1,837,600 | $9,247,000 |

| Accommodation Costs | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 | $687,000 | |

| Total Health Canada | 20 | $5,500,000 | $5,500,000 | $5,500,000 | $5,500,000 | $5,500,000 | $27,500,020 |

| CMHC | FTEs | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | Total |

| Safe houses | $0 | $800,000 | $150,000 | $0 | $0 | $950,000 | |

| TOTAL CMHC | $0 | $800,000 | $150,000 | $0 | $0 | $950,000 | |

| FTEs | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | Total | |

| Total Submissions | $20,430,000 | $20,430,000 | $20,430,000 | $20,430,000 | $20,430,000 | $102,149,000 | |

Table 3 shows a breakdown of budgeted and actual expenditures from 2005-06 to 2008-09.

| 2005-2006 | 2006-2007 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | Actual | Budget | Actual | |

| INAC | ||||

| Sheshatshiu school design | $100,000 | $90,650 | $0 | $0 |

| Education | $2,262,600 | $2,135,117 | $2,340,000 | $3,865,979 |

| Child, Youth & Family Services | $5,570,800 | $5,570,415 | $5,571,000 | $6,070,400 |

| Income Support | $438,100 | $218,525 | $1,308,000 | $649,525 |

| Electrification - Natuashish | $2,000,000 | $2,321,672 | $1,000,000 | $2,950,370 |

| Airport Agreement - Natuashish | $100,000 | $149,616 | $100,000 | $200,000 |

| A-BASE/A-BASE LIKE | $10,471,500 | $10,485,995 | $10,319,000 | $13,736,274 |

| Facilities O&M Capacity Bldg | $900,000 | $797,523 | $900,000 | $900,000 |

| Housing Capacity Bldg | $295,000 | $256,000 | $245,000 | $168,000 |

| LTS Capacity Bldg | $420,000 | $510,268 | $420,000 | $420,000 |

| Reserve Creation | $220,000 | $449,720 | $0 | $150,000 |

| Devol Planning & Transition | $150,000 | $82,800 | $150,000 | $150,000 |

| New Paths (Outpost) | $200,000 | $600,000 | $200,000 | $200,000 |

| Strategies for Learning | $555,000 | $194,696 | $400,000 | $592,800 |

| Planning & Consultation | $100,000 | $244,509 | $100,000 | $250,000 |

| Safehouses | $100,000 | $35,000 | $100,000 | $65,000 |

| Healing | $2,940,000 | $3,170,516 | $2,515,000 | $2,895,800 |

| Total INAC Grants & Contributions | $13,411,500 | $13,656,511 | $12,834,000 | $16,632,074 |

| Salaries | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 |

| EBP | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 |

| Accommodation | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 |

| Other Operating | $870,300 | $870,300 | $647,800 | $647,800 |

| Total INAC Salary & Operating [Note 14] | $1,588,500 | $1,588,500 | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 |

| Health Canada (HC) [Note 15] | ||||

| Addictions / Mental Health | $2,411,000 | $2,018,800 | $2,120,000 | $3,455,700 |

| Maternal / Child Health | $705,000 | $1,873,000 | $630,000 | $380,000 |

| Community Health Planning | $225,000 | $201,500 | $200,000 | $419,900 |

| Management & Support | $175,000 | $97,800 | $125,000 | $0 |

| Safehouses | $0 | $0 | $400,000 | $400,000 |

| Total HC Grants & Contributions | $3,516,000 | $4,191,100 | $3,475,000 | $4 655 600 |

| Salaries | $1,056,700 | $799,900 | $1,056,700 | $945,900 |

| EBP | $211,300 | $160,000 | $211,300 | $189,200 |

| Other Operating | $578,600 | $457,200 | $619,600 | $437,700 |

| Total HC Operating Costs | $1,846,600 | $1,417,100 | $1,887,600 | $1,572,800 |

| Accommodation Costs | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 |

| TOTAL HC | $5,500,000 | $5,745,600 | $5,500,000 | $6,365,800 |

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) | ||||

| Safe houses | $ | $ | $800,000 | $ |

| Total CMHC | $ | $ | $800,000 | $ |

| 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | Actual | Budget | Actual | |

| INAC | ||||

| Sheshatshiu school design | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Education | $3,075,000 | $6,562,265 | $3,485,000 | $6,792,352 |

| Child, Youth & Family Services | $5,571,000 | $9,072,805 | $5,571,000 | $8,262,094 |

| Income Support | $1,358,000 | $988,625 | $1,508,000 | $395,000 |

| Electrification - Natuashish | $1,000,000 | $3,318,000 | $1,000,000 | $4,057,704 |

| Airport Agreement - Natuashish | $100,000 | $106,000 | $100,000 | $143,000 |

| A-Base/A-Base Like | $11,104,000 | $20,047,695 | $11,664,000 | $19,650,150 |

| Facilities O&M Capacity Bldg | $750,000 | $750,000 | $600,000 | $600,000 |

| Housing Capacity Bldg | $60,000 | $60,000 | $0 | $0 |

| LTS Capacity Bldg | $320,000 | $0 | $120,000 | $693,299 |

| Reserve Creation | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Devol Planning & Transition | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 | $150,000 |

| New Paths (Outpost) | $200,000 | $200,000 | $200,000 | $200,000 |

| Strategies for Learning | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $500,000 |

| Planning & Consultation | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Safehouses | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 |

| Healing | $2,380,000 | $2,060,000 | $1,970,000 | $2,643,299 |

| Total INAC Grants & Contributions | $13,484,000 | $22,107,695 | $13,634,000 | $22,293,449 |

| Salaries | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 | $540,000 |

| EBP | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 | $108,000 |

| Accommodation | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 | $70,200 |

| Other Operating | $647,800 | $647,800 | $647,800 | $647,800 |

| Total INAC Salary & Operating [Note 14] | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 | $1,366,000 |

| Health Canada (HC) [Note 15] | ||||

| Addictions / Mental Health | $2,150,000 | $1,908,000 | $2,150,000 | $2,001,000 |

| Maternal / Child Health | $655,000 | $320,000 | $655,000 | $566,300 |

| Community Health Planning | $225,000 | $425,000 | $225,000 | $208,000 |

| Management & Support | $95,000 | $242,100 | $95,000 | $14,000 |

| Safehouses | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 |

| Total HC Grants & Contributions | $3,525,000 | $3,295,100 | $3,525,000 | $3,189,300 |

| Salaries | $1,056,700 | $1,261,100 | $1,056,700 | $1,170,000 |

| EBP | $211,300 | $252,200 | $211,300 | $234,000 |

| Other Operating | $569,600 | $472,500 | $569,600 | $506,000 |

| Total HC Operating Costs | $1,837,600 | $1,985,800 | $1,837,600 | $1,910,000 |

| Accommodation Costs | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 | $137,400 |

| TOTAL HC | $5,500,000 | $5,418,300 | $5,500,000 | $5,236,700 |

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) | ||||

| Safe houses | $150,000 | $ | $ | $ |

| Total CMHC | $150,000 | $ | $ | $ |

| 2009-2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Budget | Actual | |

| INAC | ||

| Sheshatshiu school design | $0 | $0 |

| Education | $3,635,000 | N/A |

| Child, Youth & Family Services | $5,571,000 | N/A |

| Income Support | $1,508,000 | N/A |

| Electrification - Natuashish | $1,000,000 | N/A |

| Airport Agreement - Natuashish | $100,000 | N/A |

| A-Base/A-Base Like | $11,814,000 | N/A |

| Facilities O&M Capacity Bldg | $450,000 | N/A |

| Housing Capacity Bldg | $0 | N/A |

| LTS Capacity Bldg | $120,000 | N/A |

| Reserve Creation | $0 | N/A |

| Devol Planning & Transition | $150,000 | N/A |

| New Paths (Outpost) | $200,000 | N/A |

| Strategies for Learning | $400,000 | N/A |

| Planning & Consultation | $100,000 | N/A |

| Safehouses | $400,000 | N/A |

| Healing | $1,820,000 | N/A |

| Total INAC Grants & Contributions | $13,634,000 | N/A |

| Salaries | $540,000 | N/A |

| EBP | $108,000 | N/A |

| Accommodation | $70,200 | N/A |

| Other Operating | $647,800 | N/A |

| Total INAC Salary & Operating [Note 14] | $1,366,000 | N/A |

| Health Canada (HC) [Note 15] | ||

| Addictions / Mental Health | $2,150,000 | N/A |

| Maternal / Child Health | $655,000 | N/A |

| Community Health Planning | $225,000 | N/A |

| Management & Support | $95,000 | N/A |

| Safehouses | $400,000 | N/A |

| Total HC Grants & Contributions | $3,525,000 | N/A |

| Salaries | $1,056,700 | N/A |

| EBP | $211,300 | N/A |

| Other Operating | $569,600 | N/A |

| Total HC Operating Costs | $1,837,600 | N/A |

| Accommodation Costs | $137,400 | N/A |

| Total HC | $5,500,000 | N/A |

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) | ||

| Safe houses | $ | N/A |

| Total CMHC | $ | N/A |

1.5 Program Profile

The LICHS is a long-term strategy designed to improve health and social outcomes in the two Labrador Innu communities of Natuashish (formerly Davis Inlet) and Sheshatshiu. The strategy was developed in the aftermath of a gas-sniffing crisis in the Labrador Innu communities in the fall of 2000.

The LICHS recognizes that the issues confronting the Innu have taken generations to develop, and solutions must also be long-term in nature. The strategy draws upon expert advice and evidence from the literature regarding communities in crisis, which confirm that sustained, comprehensive approaches are the most effective means of supporting community healing.

It is important to note that A-base funds aside from LICHS funding has been provided to the Innu by INAC and HC for First Nations Band administration and infrastructure, as well as for direct services related to health, education and social programs. This evaluation assessed, where possible, the community results that can be attributed to the LICHS as opposed to community investments made through A-base funds. First-level services provided to Innu are those health services provided directly to community members (e.g. addiction treatment, mental health). Second-level services are those services provided at a zone or regional level, which support the delivery of health services to community members (e.g. coordination, consultation, supervision). In the context of LICHS, the phrase 'second-level services' is used to describe the provision of capacity development, mentoring, support and advice by LHS health professionals to community-based health workers in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu.

Objectives

The ultimate goal of the LICHS is to restore the health and hope for the Innu communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu in Labrador.

Achievement of the following objectives from the 2005 Treasury Board submission will support attainment of the ultimate goal:

- Increased capacity to plan and manage their affairs in a culturally appropriate manner;

- Safe and secure living environment for residents in these two Innu communities;

- Improved health and social conditions of communities;

- Improved educational participation and attainment;

- Enhanced employability and increased economic opportunities;

- Stable and harmonious Innu communities capable of sound governance and effective program and services delivery; and

- Improved relations between the Innu of Labrador and other levels of government.

Elements

INAC has been responsible for the Relocation of the Mushuau Innu to the new community of Natuashish; Registration and Reserve Creation for both Labrador Innu communities; and other Programs and Services. PSEPC/RCMP has been responsible for Community Policing; and Health Canada has been responsible for the Community Health component, including addictions and mental health; maternal and child health; community health planning; as well as the establishment of the LHS office in Labrador.

Program Clients

Members of the Mushuau Innu and Sheshatshiu Innu First Nations residing in the communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu, Labrador.

Partnerships, Roles

First Nation Partners

The Mushuau Innu and Sheshatshiu Innu First Nations - responsible for the delivery of community-based programming. Innu Nation - responsible for representing the political interests of the Labrador Innu, including negotiations towards a land claims agreement and self‑government.

Federal Partners

INAC, PSEPC, RCMP, CMHC - responsible and accountable for their respective components of the LICHS. Strategic linkages are also fostered with other federal departments, which provide funding to the Labrador Innu, such as Human Resources and Skills Development Canada and Canadian Heritage.

Provincial Partners

The Province of Newfoundland and Labrador and the Labrador-Grenfell Regional Integrated Health Authority - responsible for the delivery of health and social services falling under provincial jurisdiction.

| Program or Activity Name | Funding Agency | Delivery Agent |

|---|---|---|

| Child Youth and Family Services | INAC | NL |

| Community Health Planning | HC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Education | INAC | NL (until August 2009) MIFN & SIFN (post 2009) |

| Income Assistance | INAC | NL |

| Integrated Management | INAC & HC | INAC & HC |

| Facilities O&M (Natuashish) | INAC | MIFN |

| Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder | HC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Family Resource Centre | HC | SIFN |

| Family Treatment Program | HC | SIFN |

| Healing Lodge (Mobile Treatment) | HC | MIFN |

| Labrador Health Secretariat | HC | HC |

| Next Generation Guardians | HC | MIFN |

| Outpost Program (New Paths) | INAC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Parent Support Worker Program | HC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Relocation | INAC | INAC & MIFN |

| Reserve Creation | INAC | INAC |

| Safehouse construction | CMHC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Safehouse operations | INAC & HC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Strategies for Learning | INAC | MIFN & SIFN |

| Wellness Centre | HC | MIFN |

Regional Offices and Labrador Health Secretariat

Regional offices of INAC and HC, and LHS play a lead role in supporting the effective delivery of programs and services in the Innu communities. HC's LHS is responsible for providing capacity development through professional support services using a staff of 14 in Goose Bay and is responsible, with the Innu, for integrating the work of the Secretariat with community‑based delivery to ensure the maximum benefit from the Secretariat. According to this RMAF, the LHS and the INAC regional office are responsible for:

- Managing and monitoring contribution agreements through established procedures that may include regular contact and discussion with recipients by means of on-site visits and reporting;

- The roll-up and analysis of regularly collected program data as laid out in this RMAF's Performance Measurement Strategy;

- Monitoring the performance of the activities and initiatives for which regional offices are accountable, and making informed decisions;

- Communicating evaluation results within the federal government and the communities;

- Supporting communities in program planning, capacity development and other aspects of program delivery and administration;

- Providing an advisory role for program policy activities; and

- Working in partnership with Innu to ensure the effective implementation and delivery of programs.

For HC, the regional office is responsible for overall accountability functions (contribution agreements), senior management functions to the regional office, as well as program coordination with core programs (shared region and LHS).

The Integrated Management of the LICHS is the joint responsibility of INAC, HC, the communities of Sheshatshiu and Natuashish, and the Province of NL. HC's responsibilities under LICHS will be implemented by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch. The Main Table provides a forum that brings together the political leadership of the Innu with senior federal management and the Special Federal Representative (SFR). The SFR chairs the Main Table and is also responsible for presenting the federal position. The specific mandate of the Main Table is to discuss, address, provide direction, and resolve issues related to the implementation of the LICHS and other emerging Innu-related issues (e.g. reserve creation for Sheshatshiu, land claims). The Main Table Issues arising from the Main Table related to resource, management or policy implications for the department(s) or government as a whole are referred to the LHS Steering Committee for discussion, advice and direction.

HC and INAC have jointly funded a Director at the EX level to oversee and coordinate the implementation of the LICHS. The Director reports to both the regional directors of INAC and HC, and will sit on the Operations Steering Committee.

The Operations Steering Committee comprises members of HC, INAC, PSEPC, Service Canada as well as the Chief Federal Negotiator (CFN). The committee meets as necessary to review issues respecting the LICHS. The federal parties also meet regularly with the Innu leadership and the CFN at Main Table to discuss issues of common interest. Main Table sub-committees have been struck in a number of areas to ensure coordination of policy and efforts.

Evaluation Process

As per Treasury Board requirements, an evaluation of the LICHS was to be completed by the Audit and Evaluation Sector in 2009-2010. However, the schedule was advanced in order to provide the report in the fall of 2009.

An Interdepartmental Evaluation Working Group (EWG) provided input and feedback on the terms of reference, statement of work, and all key deliverables. The group met as required to review and provide input on deliverables. It was led by a senior evaluation manager, INAC, and included representation from INAC, HC and Public Safety Canada. A Strategic Evaluation Committee provided additional input and feedback on the terms of reference, methodology report, and preliminary findings. It was led by the Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive, AES and included representation from INAC, HC, the Province of NL and Innu leadership.

An independent consulting firm, DPRA, was contracted to provide additional human resources to conduct the evaluation, and to provide additional impartiality. The consultant was primarily responsible for drafting the tools used in the evaluation, conducting all lines of evidence including the on-site case studies in Natuashish and Sheshatshiu; drafting the preliminary findings; and drafting the report.

2.0 Methodology

Evaluation methodology included:

- Preliminary Consultations (to inform the development of the evaluation methodology)

- Document and File Review (including secondary research sources)

- Literature Review

- Key Informant Interviews

- Community Case Studies (Interviews and Group Interviews)

While the evaluation plan originally included two expert panels intended to provide an additional independent source of opinion, this item was dropped due to differences in opinion with respect to whether an expert should be defined in terms of community expertise versus academic expertise, and the extent to which external experts could or should speak to the unique situation in the Labrador Innu communities. In addition, the Innu expressed concerns over their past experience with external panels, the method for selection of individuals, and the limited time frame for analysis and response.

Appendix A shows the lines of evidence used to answer each of the evaluation questions.

2.1 Development of the Evaluation Framework and Methods

The issues and overarching evaluation questions are as follows:

-

Relevance

- To what extent is there a continued need to support Labrador Innu communities with healing?

- To what extent do the objectives of the LICHS relate to the objectives of the Government of Canada and of the departments involved in its delivery?

- To what extent is there a continued need to support Labrador Innu communities with healing?

-

Implementation and Delivery

- Has the strategy implementation been appropriate?

- What are the lessons learned from the LICHS, for the future and for other communities?

- Has the strategy implementation been appropriate?

-

Success

- What progress has been made towards the strategy's intended outcomes, as laid out in the logic model?

- What progress has been made towards the strategy's intended outcomes, as laid out in the logic model?

-

Cost-Effectiveness

- To what extent is the LICHS meeting its medium and long-term outcomes in relation to the resources spent?

- Are there alternative programs/interventions achieving similar or better results at a lower/similar cost?

- To what extent is the LICHS meeting its medium and long-term outcomes in relation to the resources spent?

-

Future Considerations

- To what extent is the progress made under the LICHS sustainable in the context of the strategy?

2.2 RMAF and Logic Model

The LICHS RMAF articulates the key objectives of the strategy as:

- To enhance Innu governance to increase community engagement and enhance program administration (all partners) to increase quality of service delivery;

- To establish a physical environment that lays the foundation for Innu healing;

- To contribute to healthier children, families, and communities; and

- To achieve efficient delivery of LICHS through coordination of policy, programs and service delivery.

Note that the objectives in the RMAF are articulated differently than the objectives articulated in earlier policy documents (see Program Profile).

The LICHS RMAF and logic model were developed in 2007 and reflect the current phase (2005/06 to 2009/10) of the strategy (refer to Figure 1). The logic model, which is intended to guide the Healing Strategy, identifies the key activity areas, measurable outputs and intended short-term, medium-term, long-term and ultimate outcomes of the LICHS. This evaluation drew on indicators of intended outputs, short-term and some medium-term outcomes described by the logic model. Although long-term and ultimate outcomes were not expected to have been achieved at the time of this evaluation, some indicators of early progress of these outcomes are also presented.

2.3 Preliminary Consultations

Preliminary consultations began with the identification of key LICHS stakeholders, in consultation with the Evaluation Manager and the Evaluation Working Group. The evaluation team developed an invitation letter and a set of preliminary consultation interview questions and then contacted each identified individual to schedule a date/time for the interview. Some interviews were conducted in-person and others over the phone. These were conducted with nine key (current and former) representatives from the Mushuau Innu First Nations (MIFN), Sheshatshiu Innu First Nations (SIFN), INAC, and HC. See Appendix B for questions asked.

The purpose of the consultations was to:

- Refine evaluation issues and questions;

- Identify existing performance indicators;

- Identify potential data sources; et

- Identify potential expert panel and key informant participants.

2.4 Document and File Review

The document and file review was intended to provide the evaluation team with material to:

- develop program profiles and background information;

- inform the development of the Detailed Methodology Report (e.g., development/refinement of evaluation questions);

- identify candidates to be queried during key informant interviews;

- contextualize the findings to be included in the Final Evaluation Report; and,

- provide a source of data to answer/partially answer some the evaluation questions.

It also provided information to guide for the other lines of inquiry.

Figure 1: The following figure shows a logic model for the objectives of the LICHS program. The objectives are as follows:

- Efficient and effective coordination and delivery of policies, programs and services;

- Enhance Innu governance to increase community engagement and enhance program administration to increase quality of service delivery;

- Establish physical environment that lays foundation for healing; and

- Ensure communities have access to health, social and education programs and services of a quality enjoyed by all Canada.

These objectives are all linked via arrows to the key activity areas, which are as follows:

- Horizontal integrated management;

- Capacity development, program management, community governance, and devolution;

- Community infrastructure; and

- Health, social, and education programs.

These key activity areas are linked via arrows to the outputs associated with these activities, which are as follows:

- Joint plans for program implementation; priority setting sessions; and collaborative decisions;

- Support to Innu programs and workers; joint capacity development plans; and community health plans;

- Constructed safe houses, SSS school, Healing Lodge and Wellness Centre; and sustainable new facilities; and

- Implementation plan for Philpot recommendations; Outpost program; shelters and safety plans; supports/services for individuals and facilities; and recovery programs.

Each output is linked via arrows to its short-term outcomes (1-2 years), which are as follows:

- Improved relationship/trust between partners; and better integration and coordination of services;

- Increased capacity of communities to plan, deliver and evaluate services; and increased capacity to manage community infrastructure;

- Appropriate spaces to deliver programs; and

- community engagement in health planning; awareness of healthy behaviour; cultural/community appropriate services; community involvement in schools; frameworks for community health plans; and progress against the plan for Philpot recommendation.

These short term outcomes for outputs are linked via arrows to medium term outcomes (3-5 years), which are as follows:

- Increased community financial and management capacity; less interventions in band financial management; increased local staff retention; and increased use of evidence-based decision making;

- effective, streamlined, targeted and complementary programs and service; and

- sustainable programs and services; action plan for program improvement; increased adoption of healthy behaviours; increased self-esteem of community members; reduce prevalence of substance abuse; increase supports to individuals/families affected by FASD; and reduce violent crime.

These medium term outcomes are linked via arrows to long-term outcomes (>5years), which are as follows:

- Optimal integration and coordination between federal/provincial/Innu programs and services;

- Effective social and health planning and management capabilities in communities; devolution of programs and services; and effective local control and delivery of services and programs; and

- Increased percentage of children performing at grade level; improved health status; and reduced suicide rates.

All of the long term objectives are linked via an arrow to the ultimate outcomes of healthier children, families and communities; and Innu control of community.

Documents, files, meeting minutes and email correspondences were obtained from the Evaluation Manager, Evaluation Working Group, Preliminary Consultation participants, Key Informant interview participants, and from the two communities. Hard copies of information were also gathered from the INAC offices in Goose Bay, NL and Amherst, NS. Two hundred and forty‑nine files and documents were reviewed including, INAC policy documents; policy proposals; program research and evaluations; RMAF; education reports, recommendations and implementation plans; the interim LICHS evaluation; secondary sources of data (e.g., Statistics Canada community profiles); and, internal documentation (e.g., memos, Main Table and Sub-committee meeting minutes and emails). Additionally, a variety of reports, presentations, proposals, strategic plans, and correspondence were provided by the Innu communities and an Innu advisor. Appendix C lists the documents and files reviewed for the LICHS evaluation. Documents were utilised in the current report based on their relevance to providing context and background or answering specific evaluation questions; as well as the degree of redundancy between all the documents reviewed.

2.5 Literature Review

Thirty-six pieces of domestic and international literature focusing on topics of Aboriginal community healing and capacity building strategies were examined, including academic publications, national and international journals, documents published by foreign governments, and independent research publications produced for federal government departments.

The literature review was intended to provide the evaluation team with background material to:

- assess the extent of current research and literature on the topic;

- document best practices in Aboriginal community healing, where available;

- note lessons learned from domestic and international experience in Aboriginal community healing; and

- support other lines of inquiry.

The sources of literature were identified by the Evaluation Manager, Evaluation Working Group, Preliminary Consultation participants, and through internet search using the following phrases: Aboriginal community healing and (1) the social determinants of health; (2) comprehensive healing strategies; (3) best practices; and (4) evaluation of community healing initiatives. Additionally, resources were obtained from DPRA's extensive existing bibliography on Aboriginal community healing and comprehensive approaches, which includes grey literature not normally found through internet searches.

The literature was intended to inform the evaluation on the reasons for Aboriginal community trauma; the essential elements of community healing strategies; methods of implementation of healing strategies; and successes and challenges observed in the implementation of other strategies.

Appendix D lists the literature review references for the LICHS evaluation.

2.6 Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted from June to August 2009. Preliminary consultations with Evaluation Working Group members and suggestions from the Evaluation Manager and the evaluation team resulted in the identification of key informant participants. The names for additional key informants were put forth by interviewees themselves. Individuals were recommended for inclusion in the key informant interview process based upon their significant involvement in, and knowledge of, the strategy (particularly Phase II). Some individuals were suggested for inclusion due to their breadth of Healing Strategy knowledge, while others were included because of their depth of knowledge about specific aspects of it (e.g., education). Potential interview participants were contacted and asked to take part. Interviews were conducted by telephone.

A total of 27 individuals participated in the interview process. Key informants included the following current and former LICHS representatives:

- INAC (e.g., HQ, Region) (n=6)

- Health Canada (e.g., HQ, Region) (n=10)

- Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada (PSEPC) (HQ) (n=1)

- Province of NL (e.g., assistant deputy ministers) (n=4)

- Mental Health Commission of Canada (n=1)

- Academic Institutions (Memorial University, Dalhousie University) (n=2)

- Consultant Firm (n=2)

- Lawyer (n=1)

Part of the rationale for this method of selection was the extensive amount of strategy-specific knowledge required to speak to many of the evaluation issues; particularly those of relevance and implementation, but also successes, limitations, cost-effectiveness and future considerations.

2.7 Community Case Studies

Case studies for this evaluation were intended to help assess the impacts of the LICHS on both communities by spending time in the communities and discussing issues, successes, and challenges with people in the communities. Specifically, the intention was to assess the extent to which the programs and services offered under the strategy are consistent with their objectives and achieving the intended outcomes, and to assess other issues related to the strategy's overall effectiveness and impacts. The case studies also allowed community members (particularly front‑line program staff) the opportunity to express their opinions and experiences in the actual on-the-ground delivery of LICHS programs and services.

The two communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu were each visited three times between the months of April and July 2009, with two team members spending a total of 45 person days in the communities. With the assistance of band managers, a community researcher/translator was hired in Sheshatshiu and a community researcher and a community translator were hired in Natuashish to assist with translation as required; identification and contact of community members to participate in the individual and group interviews; logistics/coordination of group interviews; and with the face-to-face interviews if translation was required.

Specific tools intended for the case studies included: interviews (individual and group), focus group discussions (youth and Elders), youth education survey, and community document/data review. A total of 54 in-person and two telephone interviews were conducted (refer to Table 4).

| Interviewee Category | Natuashish | Sheshatshiu |

|---|---|---|

| Innu Leaders | 1 | 1 |

| Directors/Program Managers/ Program Coordinators | 9 | 10 |

| Program Staff | 4 | 12 |

| Elders | 2 | 3 |

| Community Members | 2 | 1 |

| Others (e.g., consultant, crown attorney, non-LICHS program staff) | 6 | 5 |

| Total | 24 | 32 |

The evaluation team developed a series of plain language (i.e. jargon free) interview questionnaires, each specific to: leaders, Elders, youth, program directors and managers, program staff, and other community members.

Case study interviewees were selected for participation based upon their involvement with, and/or knowledge of, the LICHS and/or their knowledge of community health, social, safety and/or economic issues. Other individuals were selected after having approached the evaluation team members to request an interview to express their viewpoints and experiences with respect to healing in their community.

Youth focus group sessions were organized in both communities by the local researchers but there were no attendees. Additionally, initially the evaluators intended to carry out Elder focus groups but once in the communities were told that one-on-one interviews would be more appropriate.

As a component of the community case studies, relevant community-level documents and administrative data were requested. While little documentation was obtained from community members themselves, Innu evaluation working group members shared community-level LICHS program- and service-related reports, presentations, proposals, strategic plans, budgets and correspondence through a consultant, who was included on the working group at their request.

While the case studies were intended to comprise the tools described above, not many of these tools were able to be employed, with the exception of interviews, as described in detail in Section 2.9 on limitations.

2.8 Presentation of Key Informant and Case Study Interview Findings

Where appropriate and possible, findings from other lines of evidence were used to corroborate the opinions, perceptions and experiences of key informant and case study interview participants (i.e., triangulation) in order to strengthen the confidence in the research findings. When referring specifically to key-informant or case study interview observations, viewpoints of respondents will be described as follows:

- High level of agreement – refers to ≥ 2/3 (66%) of respondents queried

- Several respondents – refers to > 10 respondents

- A number of respondents – refers to > 5 respondents

- A few respondents/Some respondents – refers to ≥ 3 participants