Archived - Thematic Indicators Project

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: September 2009

PDF Version (499 Kb, 145 Pages)

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction & Background

- 2. Overview and Scope

- 3. Research Approach

- 4. Methodology

- 5. Thematic Chapters

- 6. Health and Well-Being

- 7. Environment

- 8. Education

- 9. Economy

- 10. Governance

- 11. Infrastructure

- 12. Mapping of the Indicators to the PAA

- 13. Conclusion & Recommendations

- Appendix A - List of Indicators

- Bibliography

Foreword

The creation of sound measures to track the performance of programs at the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) is critical to developing programs that reflect the vision of Aboriginal and northern people and remain responsive to the needs of Aboriginal and northern communities. Measurement of success in these programs must move past a review of the activities of the Department, to pursue the impacts of these activities in numerous contexts. The purpose of the Thematic Indicators Project is to assist the Department in its move towards performance measurement that considers broader program outcomes among Aboriginal and northern people.

The Project is the product of a four-month summer internship based out of the Audit and Evaluation Sector that brought together eight Master's-level students from universities across the country. In addition to their work on this project, the interns were placed in INAC sectors to offer exposure to a variety of work experiences and to provide a firsthand understanding of the work of the Department. The Project builds on findings identified in a special study on Results-based Management Accountability Frameworks (RMAFs) conducted by the first cohort of INAC evaluation interns over the summer of 2008.

The approach taken to the Project was to connect the specific performance measurement needs of the Department with what matters most at the community level. The result is a discussion of indicators in six thematic areas drawn from a broad review of literature and performance measurement in other jurisdictions. The interns consulted INAC sectors, other federal departments, provincial governments and Aboriginal and community organizations to identify performance measurement needs at multiple levels among various stakeholder groups and to build on and complement work already underway.

The Thematic Indicators Project is primarily intended to guide INAC programs when developing performance measurement strategies. The report does not propose a set of prescriptive indicators, but rather encourages a shift in thinking about the purpose and spirit of performance measurement. It is hoped that the report will find use with other federal departments, various levels of government and those working diligently to measure progress at the community-level.

Nicole Kennedy

Director of Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review,

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada

Executive Summary

Introduction

The development and use of appropriate indicators is essential for greater accountability, program improvement and evidence-based decision making. Performance measurement plays a key role in monitoring and assessing the impacts of programs and is necessary for future evaluation work. In the past decade, evaluations have consistently identified that a lack of performance data has undermined the capacity of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) to undertake meaningful evaluative work. The Thematic Indicators Project, a research project produced by INAC's Audit and Evaluation Sector, is designed to inform the development of Performance Measurement Strategies (PM Strategies) and encourage the development of indictors that consider broader outcomes in Aboriginal and northern communities

This report identifies key performance indicators across six thematic areas that represent the broad scope of INAC's mandate: Health and Well-being; Environment; Education; Economy; Governance; and Infrastructure. Ultimately, this framework contributes to the measurement of INAC's vision of a future in which First Nations, Inuit, Métis and northern communities are healthy, safe, self-sufficient and prosperous.

Key Findings

Thematic Areas – Pillars of a Strong Community

A key finding that emerged early in the research was the need to take a holistic community-level approach to the selection of indicators. The project is organized around six thematic areas, each of which represents a critical area of inquiry when developing an understanding of healthy, safe, self-sufficient, and prosperous Aboriginal and northern communities. The reader is encouraged to consult Canada's Aboriginal Women: Assessing the Issues, also recently completed by INAC's Audit and Evaluation sector for ideas on how to apply a gender-based approach to these thematic areas.

Health and Well-being

Fundamentally, community well-being depends on the

physical, mental and emotional health and well-being of individual

community members. Health can also be affected by, and in turn affect

the environment, culture, family and community. The multiple facets

of individual and community development contributing to health and

well-being means that developing performance measures to satisfy

these elements is a complex and challenging task. In order to demonstrate

the relationship between program activities and community health

outcomes, health status indicators such as physical and mental health

as well as indicators that measure both the social and environmental

determinants on health such as living and working conditions, child

development and poverty are considered.

Environment

Social, cultural, and historical features of Aboriginal and northern

communities are closely tied to the land and environment. A bountiful environment

provides sustainable food production and other essential contributors of

good health. The Environment chapter draws on select quantitative and qualitative

indicators in order to measure the complex relationship the environment

shares with communities' economic, social and political processes.

Many of the environmental indicators presented are quantitative. These

indicators provide a comparable, reliable and valid description of the

health of the environment. In contrast, the remaining indicators are qualitative

and prescriptive in nature, addressing the quality of environmental management.

Together, the collection of environmental indicators creates a comparable

and reliable yet detailed picture of environmental success in Aboriginal

and northern communities.

Education

Education is intricately linked with other areas of well‑being as it prepares Aboriginal and northern people for new opportunities that will result in an increased standard of living and overall community well-being. Research on Aboriginal perspectives on learning provides a holistic lens from

which to examine the development of a successful education system. This lens

views education as lifelong, experiential and spiritual process, rooted in

traditional language and culture, and supported at the community level. A goal

of the proposed indicators is to illustrate the importance of formal and experiential

learning. The indicators focus on measures of those aspects of learning, which

prepare the individual from the beginning of their development to a self-sufficient

and participating member of society.

Economy

The socio-economic conditions in Aboriginal and northern communities

are highly complex and continue to undergo significant change. Today, Aboriginal

and northern communities are increasingly identifying and participating

in economic activities that, given adequate capacity, could provide sustainable

means for diverse cultures to flourish in Canada's dynamic economic

environment. The approach taken to economic development in this chapter

focuses on the entire economic policy story in Aboriginal communities from

the initial economic action plan through to long term growth and sustainability.

Indicators have been selected for their ability to measure the direct and

indirect factors affecting the economy.

Governance

As Aboriginal communities in Canada continue to grow, the need for strong Aboriginal governance structures that have the capacity to bring individual and community well-being to parity with other Canadians becomes

more pressing. The links between governance and social development in the areas

of health, economy, environment, education and infrastructure in Aboriginal

communities are well documented in the governance literature.Throughout the

research, we identified four sub-categories of governance activities that provide

a general scope for this broad thematic area: Principles of Good Governance;

Strong Institutions of Government; Self Government Agreements; and Strong Intergovernmental Relationships. Together, the categories provided us with a platform for selecting indicators that can assist INAC officials in understanding the governance capacity

of Aboriginal communities.

Infrastructure

The thematic area of infrastructure

was chosen as a contextual enabler of broader outcomes relating to health and

well-being, general social health, and economic opportunities. The indicators

discussed have been chosen for their ability to monitor outcomes that directly

relate to key issues of infrastructure in Aboriginal and northern communities.

The research presented few indicators that allow for an assessment of the general

state of infrastructure. While there are many operational and technical measures

for various infrastructures, few are direct indicators of higher-level performance

and outcomes.

Headline Indicators

A list of key or headline indicators with descriptions can be found in Annex A to the full report. Following the screening of hundreds of indicators discovered in the research, a broad list of twenty to fifty indicators was developed for each thematic area. The research group then discussed which of these were most applicable to the Department and to the issues facing Aboriginal and northern communities. This process arrived at a list of ten to fifteen headline indicators in each thematic area.

Indicators Mapping and Synthesis

INAC's Program Activity Architecture (PAA) was chosen as a framework of reference to depict the ways in which the selected indicators can currently be used to measure the progress of program activities toward their stated objectives and ultimately, toward the Department's Strategic Outcomes (SOs). In order to assess the applicability of indicators across INAC's current program areas, a mapping exercise was conducted to determine the relevancy of selected indicators in each of the thematic areas to the PAA. The purpose of this exercise was twofold:

- To determine the usefulness of selected indicators to INAC's

program areas; and

- To identify indicators that have broad application across program areas in the Department.

The mapping process involved aligning the top indicators in each thematic area with SO and Program Area (PA) levels of the PAA. To this end, the project team primarily consulted INAC's 2009-10 PAA element description and the 2009-10 Performance Measurement Framework. Indicators that cut across SO areas may be considered as central to the measurement of the Department's ultimate outcomes. The following is a synopsis of the relationships between these indicators and the PAA.

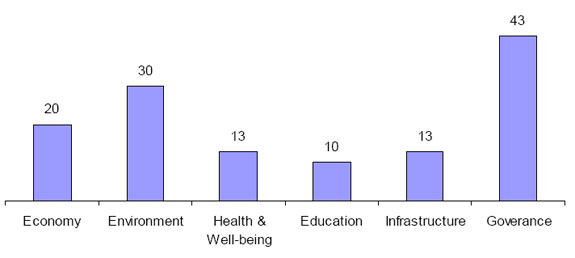

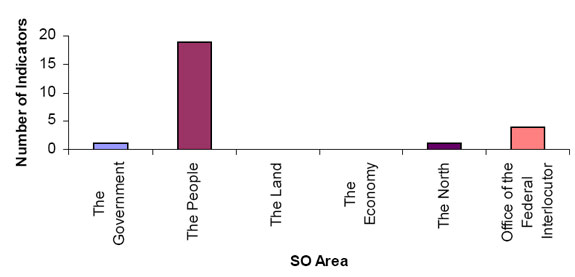

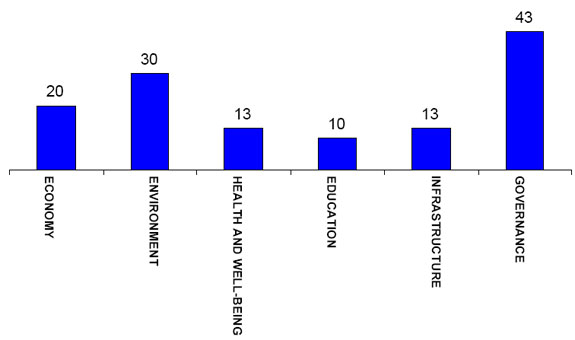

Chart 1 outlines the frequency of the headline indicators from each thematic area across the PAA. The chart shows the number of indicators from each thematic area that were aligned with indicators that could can be used to measure activities within each SO. For instance, indicators from the economy thematic area were linked to various program areas across the PAA a total of 20 times. The full report provides greater detail in the relationship between the headline indicators and departmental programming.Frequency of Headline Indicators across the PAA

Chart 1 outlines the frequency of the headline indicators from each thematic area across the PAA. The chart shows the number of indicators from each thematic area that were aligned with indicators that could can be used to measure activities within each SO. The chart shows the following frequencies for each SO: Economy: 20; Environment: 30; Health & Well-being: 13; Education: 10; Infrastructure: 13; Governance: 43.

The mapping exercise revealed that indicators for the thematic areas of Governance and the Environment surfaced most often, suggesting that the Department can benefit from integrating indicators outlined in these Thematic Chapters into multiple levels of departmental performance measurement initiatives. For example, the Governance indicator that found the highest degree of relevancy across SOs was "intergovernmental relationships" – the extent that Aboriginal communities and other stakeholders are making a joint commitment to strengthen community well-being. This indicator appeared eleven times and at least once in every SO. Likewise, the Environment indicator that found the highest degree of relevancy across the SOs was the "environmental risk management" indicator which appeared seven times and was relevant for every program activity under the Land SO. This indicator measures the extent to which communities are engaged in planning to mitigate environmental vulnerability.

The headline indicators for the thematic areas of Health and Well-being and Education did not appear as frequently as one might expect, suggesting that these indicators exceed the scope and mandate of INAC's activities. Despite not being directly linked to the PAA, attention should still be given to these indicators as they reveal important points of analysis when measuring cross-cutting issues.

Recommendations

To a large extent, the selected indicators are outcome-oriented, enabling analysis that goes beyond activities and outputs to focus on comprehensive issues and needs specific to Aboriginal and northern communities. Focusing on what is meaningful for measurement at the community-level, however, is a multi-faceted and challenging task. The diversity of Aboriginal and northern communities across Canada limits the extent to which performance information can capture the unique and complex condition of each community. The literature generally agrees on a number of factors to consider when designing a culturally-relevant performance measurement plan. Drawing from this knowledge, this report provides a starting point for the further development of indicators that meet individual community needs while simultaneously addressing the broader performance measurement goals of government.

Research for this project reveals several challenges and opportunities for the Department to consider in pursuit of meaningful and effective performance measurement. The recommendations which follow set out important steps that individual programs and the Department as a whole can take in this direction.

Recommendation 1: Differentiate between indicators related to community well-being and program success

The dual goal of the research has been to provide a list of indicators applicable both to Aboriginal / northern communities and departmental programs, which together contribute to an understanding of the Department's role in achieving outcomes at the community-level. This has meant that some indicators relate to the general well-being of communities, while others may be better suited to measuring program performance. Measures of program performance can be used to measure immediate outcomes, while measures of community well-being can be used to measure intermediate and long-term success. Differentiating between these two types of indicators contributes to an understanding of attribution between program activities and outputs and community outcomes.

Recommendation 2: Engage communities and other stakeholders in a culturally appropriate manner that integrates gender-based perspectives in developing performance measures.

Developing performance measurement indicators that are relevant at the community level requires extensive consultation with Aboriginal and northern communities to ensure that the proposed indicators and measures have meaning for the community, are appropriate to culture and gender, and are rooted in the vision Aboriginal and northern peoples have for their communities. Importantly, this requires engaging community members that represent the many different groups in a community including men, women, elders, youth and others. Attempts to collect data in Aboriginal communities should also be sensitive to the community's principles of research and data collection. One example are the principles of Aboriginal ownership, control, access, and possession of information (OCAP).

In addition, performance measurement requires consultation and partnership with other stakeholders, namely other federal departments and governments that are working toward similar outcomes. Preliminary contact made with external stakeholders during this project revealed that there are similar efforts in indicator work underway, offering opportunities for sharing of best practices, harmonizing data collection, and ultimately, creating more sophisticated performance measurement systems.

Recommendation 3: Continue to work towards harmonized data collection

The shortage of data sources focusing on Aboriginal people, within and outside the Department, makes collecting information on a number of the indicators selected for this study costly, time-consuming and in some cases unfeasible, despite their relevance at the community level. Existing data are often unable to be disaggregated to analyze the broad spectrum of variables contributing to the well-being of individual Aboriginal and northern communities. The research also found evidence of increasing data collection and indicator work already underway in Aboriginal and northern communities. While this demonstrates a growing commitment to performance-based programming, it also increases the reporting demand on individual communities.

In some cases, the same or similar data is currently being collected by multiple sources. The fact that these and other organizations share similar outcomes and goals further demonstrates the need to harmonize data collection. Coordinated collection between the federal government, other levels of government and Aboriginal/community organizations, would reduce the reporting burden. In addition to benefiting communities, increased coordination of data collection would decrease the time and cost that data collection agencies and communities face.

Recommendation 4: Develop community-based targets

Few of the indicators reviewed in this report have included targets to assess substantive progress in Aboriginal and northern communities. For the most part, the selected indicators use benchmarks to define progress as an increase of parity between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginal populations. While this approach illustrates Aboriginal community well-being in relation to national standards, it comes at the cost of observing progress from the perspective of the community itself. To gain a better understanding of community well-being, the Department should engage communities in developing benchmarks that reflect their goals and aspirations, enabling analysis of a single community's progress over time.

Recommendation 5: Pursue measurement strategies that focus on building capacity

The research identified a strong relationship between community capacity and the achievement of outcomes. However, few indicators exist for measuring the state of capacity across multiple thematic areas. The literature indicates that capacity is a function of a range of variables contributing to community well-being. In an effort to draw attention to community capacity, this report has emphasized the relationships between these variables as they surface in each Thematic Chapter. Users of this report are encouraged to adopt a holistic approach to performance measurement to capture the broad factors contributing to community capacity. Similarly, the Department is advised to continue to work towards developing programming that cuts across outcome areas to address the many unique needs of communities.

Recommendation 6: Continue the pursuit of outcome-based indicators

A major focus of this report has been to help address the shortage of outcome-oriented indicators in the Department. A key consideration in the selection of indicators has been to identify those that go beyond descriptive measures of departmental activities to include the longer-term impacts of programs. Other selected indicators roll-up operational-level data to provide an understanding of the performance of community systems, such as various types of infrastructure. Collecting performance data on outcome indicators may necessitate engaging program recipients in continuous dialogue regarding the cumulative effects of programs.

1. Introduction & Background

The development and use of appropriate indicators is essential for greater accountability, program improvement and evidence-based decision-making. Performance measurement plays a key role in monitoring and assessing the impacts of programs and is necessary for future evaluation work. In the past decade, evaluations have consistently identified that a lack of performance data has undermined the capacity of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) to undertake meaningful evaluative work. This same issue has been observed in the recent Management Accountability Framework assessment which recommended that INAC "continue work enhancing availability of sound performance data to support improvements in quality of evaluations and development of multiple lines of evidence."

A 2008 study of 59 INAC Result-based Management Accountability Frameworks (RMAF) revealed that while the Department's RMAFs were generally of good quality, measurement of program performance has been limited to focusing on expenditures and output indicators rather than outcomes or expected results. Moreover, implementation and data collection gaps have contributed to a lack of performance data and a rigorous measurement / data collection strategy.

The Thematic Indicators Project, produced by the Audit and Evaluation Sector at Indian and Northern Affairs (INAC), is designed to provide a substantive tool for programs in the selection of indicators during the development of Performance Measurement Strategies (PM Strategies). Given the broad scope of the project, it is also hoped that other federal departments and agencies and others working to achieve community-level outcomes will benefit from this information when developing performance measurement plans.

2. Overview and Scope

Policy and program work conducted by INAC is embedded within complex historical and present day challenges. Specific social, cultural and historical contexts impact program development, implementation and eventual outcomes. Developing culturally relevant and meaningful indicators that truly reflect the programs and communities they serve is a challenging task.

Given the breadth and complexity of INAC programming and the Department's broad mandate, the researchers undertook a national and international scan of indicators in the following six key thematic areas: Health and well-being, Environment, Education, Economy, Governance and Infrastructure. Most importantly, key indicators have been selected to address needs and issues relevant to Aboriginal and northern communities. Analysis, in turn, focuses on how success is defined at the community level in each of the thematic areas of analysis. Together, the full set of indicators in each of the following thematic areas is intended to offer a broad reflection of the many elements associated with a flourishing community. Finally, the selected indicators were mapped to INAC programming via the Department's Program Activity Architecture (PAA). The reader is encouraged to consult the complimentary report to this project, Canada's Aboriginal Women: Assessing the Issues – also prepared by the Audit and Evaluation Sector – for ideas on how to apply a gender-based approach to the thematic areas covered in this paper.

Health & Well-being

Fundamentally, community well-being depends on the physical, mental and emotional health and well-being of individual community members. Orientation toward local health issues is important in any model that describes Aboriginal capacity building.[Note 1] Community-based

healing has been found to be an effective solution to a multitude of community problems.[Note 2] In the words of one participant in a study of Aboriginal women's health in Manitoba: "The need for the community to be well … begins with each of us."[Note 3]

Environment

Much in the way personal health is reflected in one's community, the social, cultural and historical health of the community is closely tied

to the land and environment. For many Aboriginal people, cultural identity – the very fabric of community – is inextricably bound to place. It follows that community health is dependent on the health of the environment. A bountiful

environment provides for sustainable food production and other essential

contributors of good health. From an Aboriginal perspective, sustainability

of the environment is synonymous with spiritual, economic and social survival.[Note 4]

Education

The survival of the community depends on child development and education. Without a strong and concerted effort to educate Aboriginal and northern youth, future community leaders may suffer from a lack of employability and an eroded sense of self-identity and self-worth.[Note 5] Furthermore, the cultural well-being of the community may be jeopardized by the diminished

capacity to transfer knowledge across generations. Education is intricately

linked with other areas of well-being as it prepares Aboriginal and northern

people for new opportunities that will result in an increased standard of

living and overall community well-being.

Economy

In 2006, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples noted that the economy posed the greatest challenge for Northern peoples.[Note 6] The socio-economic conditions in Aboriginal and northern communities are highly complex and continue to undergo significant change. From the redistribution

of wealth during potlatch ceremonies on the West Coast to the estimated

$40 million dollars of food produced annually by Inuit, much of the well-being

of communities depends on the local economy.[Note 7] Today,

Aboriginal and northern communities are increasingly identifying and participating

in economic activities that, given adequate capacity, could provide sustainable

means for diverse cultures to flourish in Canada's dynamic economic

environment.

Governance

It is broadly accepted in the literature that good governance and capacity to govern are foundational elements of a healthy and well-functioning community.[Note 8] Without governance capacity, First Nations would not be able to claim the right

of self-determination, which brings continued cultural strength and self-sufficiency.[Note 9] Aboriginal

people engage in diverse forms of political and social organizations. Despite

this diversity Aboriginal people share common aspirations for strong and

self-sufficient governance. As communities continue to change and grow,

the need for strong Aboriginal governance structures that have the capacity

to bring individual and community well-being to parity with other Canadians

becomes more pressing.

Infrastructure

At last, the thematic area of infrastructure is a contextual enabler of broader outcomes relating to health and well-being, general social

health and economic opportunities. For instance, adequate housing is

related to a number of health and well-being outcomes including security

and physical health. Access to high speed internet permits connection

to one's community and wider information networks and enables those

in remote communities to engage web-based economies.

It is important to note for the purposes of comparison that a number of Aboriginal community well-being indices administered in Canada target the thematic areas selected for this project. For instance, a recent study found that health, education and economy are three of the most commonly covered thematic areas in measurement tools and conceptual models. Likewise, the same study found that measures of leadership/governance and environment were also often included in index data collection.[Note 10]

3. Research Approach

3.1 Community-level Performance Indicators

Performance measurement targets various levels of analysis. Indicators developed for the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, for instance, draw from country-level data, focusing analysis on world and regional trends.[Note 11] Organizations such as Statistics Canada and provincial data collection agencies may develop indicators and data collection approaches that enable comparison of national or sub-national regions.[Note 12] A more detailed approach to performance measurement seeks to determine the condition a single community, taking into consideration key issues and priorities that most meaningfully contribute to the development of that community. Community-level indicators often go beyond high-level descriptive measures to integrate individual values and character into performance measurement.[Note 13] These indicators offer the opportunity to view issues from a systemic or institutional perspective that is often difficult to gather at the individual level.[Note 14]

It is challenging to find community-based indicators for Aboriginal groups in Canada because of the diversity of the Aboriginal population. Broadly speaking, there are three main Aboriginal groups Canada: First Nations, Métis and Inuit. There are numerous northern communities comprised of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal individuals. Among these groups are countless communities ranging from rural and isolated First Nations and Inuit settlements to urban Aboriginal people. Each community has different needs, priorities and ways of measuring their own success that departmental performance measurement must be sensitive to. The indicators explored in the following thematic chapters offer ideas for promising ways to measure some of the more significant issues facing Aboriginal and northern people at the community-level. These indicators can tell only part of the story of the impacts of government programs on Aboriginal and northern communities. For a fuller understanding of the cultural circumstances of individual communities, the reader is encouraged to couple these indicators with others that seek to explain how the progress of Aboriginal and northern communities is framed in the context of unique histories, cultural practices and ideas for how to sustain community well-being into the future.

3.2 Aboriginal Approaches to Performance Measurement

To gain a greater appreciation of how Aboriginal peoples understand the world, a review of several models and other studies help reveal pillars of a healthy Aboriginal community. It is equally important to note that Aboriginal models often go beyond objective analysis to include direct experience, interconnectedness, relationships and values, all of which can be difficult to adequately explain, much less measure.[Note 15] Finally, the broad thematic areas reviewed in this report, selected in part to reflect the current state of programming in the Department, do not cover all of the components of a healthy community identified in the literature. As a result, this guide should be used as a starting point for beginning to understand Aboriginal and northern conceptions of the world and notions of community well-being.

An Aboriginal view of the world is often considered to be holistic. This holistic perspective looks at the individual, family, community and nation; the body, mind, spirit and heart; the animal world; the sun, water and air.[Note 16] It centres around the balance of these and other aspects of human life that include the physical and spiritual as well as the surrounding natural environment. According to a conceptual framework developed for the Regional Health Survey (RHS), "[f]or First Nations peoples, community wellness is related to the mental, physical, cultural and spiritual well-being of both the individual and the community."[Note 17] In order to capture the full scope of what constitutes a healthy community for Aboriginal people, it is necessary to take a multi-dimensional approach in viewing the community.

One way to conceive of an Aboriginal worldview is through socio-ecological analysis. A socio-ecological approach to community health posits that "good health is a product of reciprocal interactions between individuals and environments that shape their lives."[Note 18] One author broadly describes socially-determined community health as a function of social, cultural, educational, economic and political environments. A key idea in this context is the interrelationship between individual health and balance with one's environment[Note 19].One important study on indicators related to humans and their surroundings is The Well-being of Nations written by Robert Prescott-Allen. This study focuses on sustainability in the assessment of quality of life and the environment in 180 countries through the use of four indices including the Human Wellbeing Index (HDI), Ecosystem Wellbeing Index (EWI), the Wellbeing Index (WI) and the Wellbeing/Stress Index (WSI). The first two indices offer comprehensive measurements of human well-being and environmental quality. The remaining can be used to compare the relationship between quality of life and the environment.[Note 20]

4. Methodology

4.1 Scope, Duration & Methods

This project was completed by a team of eight graduate-level interns who worked collaboratively over the course of four months to fully examine each thematic area. While the scope of the project was directed by the activities of the Department and the research broadly reflects the many Program Areas of INAC's Program Activity Architecture (PAA), the intent was to also address common areas of importance in Aboriginal and northern communities discussed in the literature. The goal of this approach is to establish a research scope that encompasses both high-level activities of the Department and issues identified as holding special importance to Aboriginal and northern community development and capacity building. The following research methods were used to gather information to this extent:

4.1.1 Phase 1: Data Collection

A. Literature Review

The purpose of the literature review was (i) to define the concept of

community-level performance measurement and identify best practices and

promising performance indicators and (ii) to review Aboriginal perspectives

and cultural knowledge frameworks to isolate indicators that measure what

is most meaningful for Aboriginal and Northern communities. To this end,

the project team identified and reviewed indicator-related literature

including national and international jurisdictions, Aboriginal organizations

and other community-based projects. The types of literature included in

analysis include peer reviewed journals, grey literature and other studies

published at the community level. A detailed bibliography of all sources

can be found at the end of this report.

B. Document and file review

The project team reviewed departmental performance measurement documentation

including the Program Activity Architecture (PAA), Performance Measurement

Framework (PMF), Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP), Department Performance

Report (DPR) and the 2008 RMAF study, State of Performance Measurement

of Programs in Support of Evaluation at INAC. Though not discussed

in detail in this report, these documents were indispensible when determining

the relevance of indicators to the activities and objectives of the Department.

C. Departmental Engagement & Outside Interviews

Assistant Deputy Ministers from all INAC sectors were contacted and asked

to provide contact information for a sector lead with knowledge in performance

measurement work underway. Sector representatives were asked about lessons

learned and their specific needs when developing performance measures. Other

federal departments and provincial governments and Aboriginal / community

organizations were contacted and asked to provide input into the project

based on their expertise and what they felt were pressing needs in the field

of performance measurement. These organizations provided insight into some

of the broader issues to consider when selecting indicators, such as opportunities

for streamlining data collection and measuring success across departments,

governments and sectors.

4.2.1 Phase II: Analysis

D. Indicator Analysis & Criteria for Selection

Following the screening of hundreds of indicators discovered in the research, a broad list of twenty to fifty indicators was developed for each thematic area. The research group then discussed which of these were most applicable to the Department and the issues facing Aboriginal and northern communities. This process arrived at a list of ten to fifteen headline indicators in each thematic area.

Although the researchers did not conduct a rigorous analysis

of promising indicators based on a hard set of criteria, a number of factors

were given consideration when determining which indicators to include in

the select list for each thematic area.

- Utility.Extent to which indicators have broad applicability

across the thematic areas and can be used by programs in multiple areas

of the Department

- Applicability.Extent to which indicators have particular relevance to Aboriginal and northern communities and can be used to compare progress in these communities.

- Comparability.Are there indicators being used by other

jurisdictions that could be applied to INAC programs?

- Availability. How are indicators used and collected?

What is the source of data? How often is data collected?

- Reliability. How reliable are data sources and methods

of inquiry? Have they been tested or implemented among Aboriginal and/or

northern communities?

- Validity. How well does the indicator address outcomes

or success as it is defined in each thematic area?

- Feasibility. Overall, is the indicator a feasible option for performance measurement at INAC? Is it possible to implement?

E. Mapping of the Indicators to the PAA

A key component of the Department's strategic management, the Program Activity Architecture was chosen as a framework of reference to

depict the ways in which the selected indicators can currently

be used to measure the progress of program activities toward their stated

objectives and ultimately, toward the Department's Strategic Outcomes

In order to assess the applicability of indicators across INAC's current

program areas, a mapping exercise was conducted to determine the relevancy

of selected indicators in each of the thematic areas to the PAA. This exercise

contributes to the utility of the project through the alignment of indicators

with program areas based on their identified activities and objectives.

Moreover, headline indicators with broad application across the PAA have

been revealed through this process.

4.1.3 Phase III: Reporting

The principal findings of this project are a set of indicators that offer insight into many different departmental activities. A final section of the report discuses conclusions broadly drawn from the research and offers recommendations for continuing to improve performance measurement in the Department. These findings were presented to INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in September, 2009 and, following approval, have been made available to INAC, other federal departments and the broader public.

4.2 Research Limitations

This research project undertook the task of identifying a suite of indicators that meet two separate and at time competing objectives. On one hand, the project focuses on identifying intermediate and ultimate or "high level" outcome indicators. On the other the hand, it was considered imperative that selected indicators be assessed and included based on their applicability and relevancy at the community level. This presented a significant challenge because intermediate and ultimate outcome indicators may be very broad in nature and may therefore be applied as strategic measures to evaluate multiple experiences or social conditions. However, indicators operating at this level may not, in all cases, be of use or provide information of interest to particular Aboriginal and northern communities in Canada. According to Chouinard & Cousins, Aboriginal peoples do not tend to compartmentalize, demarcate or contain their experiences as outcomes are often integrated into the culture and broader community.[Note 21] Therefore, although selected indicators will retain a high degree of relevancy at the policy level, a single indicator may be better suited for a particular community or program activity than to another.

Throughout the research phase it became clear that there is no clear methodology for assessing community development across First Nations, Métis and northern communities. Although several different frameworks acted as a research guide, no single method was available that could reasonably encompass Canada's diverse Aboriginal and northern populations. Therefore, readers should be aware that indictors were developed from a broad base of methodological perspectives that may only be applicable in particular cultural contexts.

Both objective and subjective indices are needed to understand the quality of community life. Yet, for those indicators requiring consideration for particular context, there exists an additional challenge for data collection. Although the indicators selected are among the most relevant, culturally specific indicators may, in many cases, require significant financial and human resources in order to collect. This is particularly the case for assessing programs that deliver services to urban Aboriginal individuals and communities as there continues to be a significant discrepancy in research and data available about this population.

Finally, considerable communication with experts across INAC and other federal Departments was undertaken for the project. However, only two external organizations were consulted about indicator selection. Thus, report findings are limited to the perspectives found in the literature and across the federal government. Further consultation is required in order to develop indicators and measurement models that are validated and recognized by Aboriginal and northern communities.

5. Thematic Chapters

Discussion of Thematic Chapters that follow focuses on (i) the context or issues facing Aboriginal and northern communities, (ii) rationale or reason for selecting the indicator (i.e. how the chosen indicators address key outcome areas) and (iii) assessment / analysis. Assessment of each indicator, to which the most attention is given, is based on its practical applicability to INAC including: the context in which the indicator is being used and understood by other organizations/jurisdictions; the relevance and comparability to INAC programs; and strengths and weaknesses of the indicators.

Community-level indicators are generally presented in one of two ways: (i) Measures of the governmental, economic and social systems operating in a community and (ii) measures at the individual or household level that contribute to broader outcomes of the community. It is noteworthy that a number of the indicators discussed in this study – for instance literacy rate – are not inherently community-based and may have been chosen in part because they offer the opportunity for data comparison with other jurisdictions.

The application of these indicators at the community-level depends on the selected unit of analysis and the scale at which data are reported. For example a geographical unit of analysis (i.e. person, household, neighbourhood, city, province, etc.) may be reported as the total number of persons in a community, communities in a region, households in the nation, etc. Analysis can also be used to compare indicators of a single Aboriginal or northern community to another, or to national or international benchmarks.

6. Health and Well-Being

6.1 Introduction

Recurrent in the literature on Aboriginal health and related health indicators is the fact that Aboriginal peoples' health is in a concerning state when compared to their non-Aboriginal counterparts. The Human Development Index (HDI) for the registered Indian population shows that while scores on the HDI have increased between 1981 and 2001, this progress has been slow and has left Aboriginal communities behind the rest of Canada.[Note 22] Examining health and well-being can be a daunting task, as this area covers all facets of human existence. According to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples:

Aboriginal people from almost every culture believe that health is a matter of balance and harmony within the self and with others, sustained and ordered by spiritual law and the bounty of Mother Earth.[Note 23]

Aboriginal people often describe health as a balance between various elements in which all things are interconnected: "Indigenous ideologies embrace a holistic concept of health that reflects physical, spiritual, emotional and mental dimensions. However, it is the interrelatedness of these dimensions that is perhaps most noteworthy."[Note 24] Health can also be affected by and in turn affect the environment, culture, family and community. These elements do not act in silos but connect with one another, influencing the community at all levels.

The multiple facets of individual and community development contributing to health and well-being means that developing performance measures to satisfy these elements is a complex and challenging task. Measuring wellness forces us to expand our thinking about health beyond concerns of merely the physical person to include the entire human being in the broader context of the community. The complexity of this area suggests that there are hundreds of indicators available to measure various elements of health and well-being. Developing a comprehensive picture requires considering health status indicators such as physical and mental health as well as indicators that measure both the social and environmental determinants on health such as living and working conditions, child development and poverty.

Throughout the analysis, this section considers various Aboriginal frameworks for selecting culturally relevant indicators. We have based our approach to indicator definition on the principles outlined in the First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) Cultural Framework. The RHS Cultural Framework begins by defining health as "the total health of the total person within the total environment."[Note 25] This definition suggests strong interconnectedness between individuals and the community. The RHS cultural framework encourages us to consider a dynamic array of indicators as contributing to the overall health and wellness of the individual.

Looking at health from a holistic and social determinants lens allows us to more fully understand individual and community factors affecting health. It is impossible to suggest only a few indicators that are comprehensive enough to examine important trends. The indicators we are suggesting are therefore broad, composite indicators containing a variety of sub-indicators and possible measures. Sometimes, using one or two sub-indicators is sufficient, as programs may seek out snapshot of a certain area in health and well-being. At other times, a deeper analysis will be required. In such cases, all sub-indicators can be used and the measures can be combined with indicators appearing in other thematic areas to illustrate a more comprehensive picture.

The following section provides a detailed analysis of health and well-being indicators that research shows to be among the best for portraying a holistic perspective of the current state of Aboriginal and northern communities in Canada.

6.2 Findings

1. Physical Health

Context

One of the most basic elements of health and well-being is physical health. Developing performance indicators to measure physical health requires us to look at a myriad of factors that have the largest impact on the health of Aboriginal and northern populations at the community level. Research on Aboriginal health conditions continually shows that Aboriginal people are more at risk of developing serious health problems than other Canadian populations.[Note 26] Aboriginal communities face higher rates of diabetes, obesity, heart disease and have a lower cancer survival rate than their non-Aboriginal counterparts.[Note 27]

Health Canada is the primary department responsible for Health on reserve and in northern communities. Health Canada reports on vital statistics such as birth weight, mortality rate for various diseases, years of life lost due to suicide or unintentional injuries as well as the incidence rate of sexual transmitted diseases, infections and other diseases.

Rationale

In this report, Physical Health is measured with two components in mind: (i) Morbidity and Mortality and (ii) Disability and Chronic Disease. A number of measures of Morbidity and Mortality such as life expectancy at birth are long established measures of physical health and can be disaggregated to individual populations. These measures also reflect the status of health care and the effectiveness of preventative care.

Measuring Disability and Chronic Disease allows us to assess the long term trends in disease rates. It is also linked to life expectancy as lower death rates may indicate success in disease prevention, detection and treatment. Measures such as ‘rate of unintentional injuries' allows us to measure the adequacy and effectiveness of injury prevention efforts, including public education, community and road design, prevention, emergency care and treatment resources.[Note 28]

Assessment

The Morbidity and Mortality indicator, along with its sub-indicators and measures is universal, which means it can be used in different populations and settings. It is a proven acceptable measure of assessing individual health in a population and it is sensitive in that it can measure changes over time that are of interest to INAC and to the communities that it is serving. The mortality rate measure allows for comparisons of death rates between two or more populations by adjusting for differences in population age distribution. However, the indicator is currently difficult to measure for Aboriginal populations alone. Moreover, it does not account for health behaviours that influence physical health such as the rate of drug/alcohol consumption and smoking.

Disability and Chronic Diseaseis a simple measure. However, one weakness is that it does not assess the socio-economic context (the social determinants) and root causes. To optimize measurement, the indicator must be measured over time to show improvements or setbacks in a specific population.

2. Emotional/Mental Health

Context

The state of mental and emotional health among Aboriginal peoples is of major concern for many communities across Canada, both rural and urban. Many mental health problems arise due to a variety of physical experiences and conditions including abuse, poverty, poor housing, loss of language and discrimination. Therefore, mental and emotional health cannot be understood in isolation of other aspects of health and well-being such as physical health, rates of poverty and community history. This view is consistent with the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal people which states:

Among the First Nations and Inuit communities, the term mental health is used in a broad sense, describing behaviours which make for a harmonious and cohesive community and the relative absence of multiple problem behaviours in the community, such as family violence, substance abuse, juvenile delinquency and self-destructive behaviour. It is more than the absence of illness, disease or dysfunction — it is the presence of a holistic, psychological wellness which is part of the full circle of mind, body, emotions and spirit, with respect for tradition, culture and language.[Note 29]

Rationale

According to Lalonde any attempt to measure the health of Aboriginal communities would need to compensate for the effects of the "disconnection" that is the legacy of residential schooling and other forces of assimilation.[Note 30] For that reason, special attention would need to be paid to contemporary efforts to provide opportunities for interchange across generations."[Note 31] Furthermore, the Health Council of Canada reports that many residential school survivors have been unable to establish effective relationships within their communities as a result of being taken away at an early age.[Note 32] Thus, the usual parenting, role modeling and social bonds that occur with other members were severely and permanently damaged as a result of the residential school legacy. In an effort to understand this "disconnection" between Aboriginal generations, the State of Emotional and Mental Health indicator places significant emphasis on measuring for the effects of residential schools on individuals as well as the intergenerational impacts that persist today. Possible measures of individuals' mental and emotional health as a result of the residential school legacy include, but are not limited to, the following:

Headline Measures

- Proportion of community members who attended residential school (living

and deceased)

- Self reported mental health (measures the percentage of the population

aged 18 years and older who reported their level of life stress as "quite

a lot.")

- Level of satisfaction with life

- Perceived happiness

- Suicide rates (measured across a range of ages) including attempted

suicide and suicide ideation

- Reported experience of discrimination

Other Measures

- Education attainment (see Education Thematic Chapter)

- Rate of unintentional injuries (see Physical Health indicator)

- Alcohol and drug abuse rates

- Rate of children born with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and fetal alcohol

effect (FAE)

- Rates of sexual abuse

- Rates of eating disorders

- Rates of sleeping disorders

- Rates of chronic physical illness (see Physical Health indicator)

Assessment

Data for the Emotional and Mental Health indicator is available from diverse sources such as Health Canada, INAC statistics and Statistics Canada. To date, however, no single index has been developed to specifically measure the impacts of residential schools on community health and well-being. Because individuals respond to and cope with experiences related to the history of residential schools in diverse ways, this indicator may be best measured against other health and well-being indicators listed in this report such as Physical Health and the Community Engagement indicators. According to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2003), "communities have found strength in another unanticipated residential school impact; namely, the friendships and alliances built among students from different communities, nations and people."[Note 33] Thus data from several composite indicators can be reliably measured to determine the state of emotional and mental health of both communities and individuals.

3. Quality and Appropriateness of Health Services

Context

Aboriginal and northern communities often lack capacity to access appropriate health services. Sometimes, only essential primary health care is available locally. For the most part, health services are provided by the federal government. Depending on the number and extent of transfer agreements in the community, these services may not meet the needs of the population, particularly if there is no diversity in the availability of health care professionals and diagnostic treatment options.

Rationale

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined three principal goals for health-care systems as: contribution to good health, responsiveness to the expectations of the population and fairness of financial contribution. Measuring the quality of a health care system and its appropriateness (that is, the extent to which it meets community needs), is an important measure because it determines whether a community's physical and emotional health and healing needs are being met. Inequitable health care may act as a barrier to accessing or developing health promoting behaviours, resources and opportunities.

Assessment

This indicator allows us to determine health care needs for individual communities and to assess health service and delivery across a number of characteristics with the ultimate goal of improving health services and making them relevant. As such, this indicator may assess:

- Issues of accountability and fragmented delivery

- The ability of the health system model to tackle chronic disease – a

large factor of morbidity and mortality

- The extent to which the health system accounts for culture or language

- The extent to which the health system accounts for the social or economic

determinants of Aboriginal and northern people's health

- The extent to which community needs may fall beyond the coverage received

through the Non-Insured Health Benefit Plan

- The availability of appropriate health service professionals

While these are integral characteristics for determining the quality of health care provision, some of them are difficult to measure and compare because they are often community-specific. As such, this indicator is not necessarily a simple measure but is a policy-relevant indicator focusing on bettering the health system so necessary for individual and community health and well-being.

4. Accessibility and Use of Health Services

Context

Aboriginal and northern communities are often further burdened by limited access to resources that could ameliorate health problems.[Note 34] According to the Assembly of First Nations, Aboriginal peoples are less likely to receive quality care due to waiting time and the fact that no services are available at the required location and time.[Note 35]

Rationale

This indicator, taken together with the Quality and Appropriateness of Health Service indicator, allows us to further assess the extent to which health services are achieving their goals of serving community needs and how the community is able to benefit from them. Accessibility and Use of Health Services assesses the extent to which health services are usable by the population which they are meant to serve. The indicator recognizes that geographical isolation and lower socioeconomic living conditions may mean that it is harder for Aboriginal and northern people to access the services which they need to support their health and well-being. Moreover, it allows us to identify a variety of conditions which prohibit access to health services such as poverty and geographic limitations.

Assessment

Existing data on barriers to access of health services is available through the Regional Health Survey (RHS), but available only for First Nations people living on reserve. Equivalent information for Métis and Inuit populations is not available. The challenge of this indicator is determining what is considered appropriate access and, given the geographic isolation of some communities, what might be done to remedy limited access. The benefit of this indicator is that it can be compared across Canada to encourage standards which bring Aboriginal and northern communities in line with provincial standards.

5. Community Engagement

Context

According to the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996), "the health and well-being of individuals depend in part on community health and social dynamics."[Note 36] The variety of values and norms of a society influence the health and well-being of individuals within communities and contribute to positive feelings of cultural identity and increased cultural continuity. The focus of the Community Engagement indicator is to look at how communities can contribute the overall health and well-being of their members through social cohesion and participation.

Culture and tradition are integral components of First Nations' holistic approach to health and well-being. According to Lalonde (2005), "feeling ‘connected to' and ‘valued within' one's community is associated with all manner of positive health and outcomes across the lifespan."[Note 37] Traditional activities such as ceremonies, dances, potlatches and healing circles help to sustain culture in the community and its subsequent generations. A lack of cultural connection is frequently cited as a primary cause of many of the social problems facing First Nations.[Note 38]

However, community engagement indicators need not be restricted to traditional activities. While the benefits of engaging in traditional activities, particularly language, are well documented, Aboriginal communities across Canada experience different degrees of acculturation and may therefore engage in community events that reflect a range of contemporary and traditional activities.[Note 39] Community engagement may also include engaging members in decision-making about community infrastructure and governance. Thus, the Community Engagement indicator measures the extent to which community members are connected to one another through a variety of activities that promote cultural continuity, civic engagement and knowledge transmission in an effort to preserve culture while at the same time measure community progress.

Rationale

The 2002/2003 Regional Longitudinal Health Survey found that "traditional cultural events are important to most people, regardless of their age, gender, income, education, First Nations language skills or their community's size or isolation."[Note 40] By measuring the extent to which members across communities engage in both traditional and non traditional activities, INAC's programs can develop a better understanding about the cultural context of Aboriginal and northern peoples. This allows INAC, on a departmental level, to monitor social progress in Aboriginal and northern communities across Canada.

There are several options for measuring Community Engagement. Depending on the community and cultural context, this indicator may be measured based on the following:

Headline Measures

- Percentage of community members who identify with the community's

cultural history, language and traditions

- Number of community or group celebrations/year

- Rates of participation in traditional spiritual ceremonies or rituals.

For example, participation rates in tribal council games or gatherings

and other national or international Aboriginal initiatives

- Percentage of Aboriginal learners (degree to which they are engaged in traditional practices)

Other Measures

- Number of religious or spiritual spaces available (i.e. churches,

sweat lodges) in the community

- Number of available recreation and employment programs

- Rates of participation in recreation and employment programs

- Degree to which individuals can identify a shared purpose and vision

for the community

- Number of cooperative associations in the community

Assessment

Community engagement can be difficult to measure due to the multifaceted and varied dimensions of culture. One of the more common indicators of preservation of First Nations culture is the use of Aboriginal language. Reliable data on non-traditional recreational and employment activities is currently available from the 2006 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS). However, while certain traditional activities such as hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering plants are well documented by the APS and the RHS, whole collections of activities such as storytelling, cultural games and ceremonies are often overlooked because they fall outside the current conception of "traditional." Therefore, a re-examination of what constitutes activities involved in community engagement is necessary in order to effectively evaluate community progress and social cohesion. The vast numbers of activities that contribute to community engagement make it difficult to assess communities based on single criteria.

6. Community Safety

Context

Aboriginal people have historically been over-represented in the judicial system.[Note 41] According to Correctional Services Canada, "Aboriginal offenders continue to be disproportionately represented at all levels of the criminal justice system, including in the federal correctional system."[Note 42] At the end of March 2006, Aboriginal people represented 16.7% of federally-sentenced offenders compared to 1.7% of the Canadian adult population. Aboriginal incarceration impacts whole communities and "its measures highlight the level of the equality of justice and comments on the ability of western forms of justice to meld with traditional forms of Aboriginal justice." [Note 43] Therefore, it is important to document this trend and monitor changing conditions in Aboriginal communities.

However, incarceration rates alone are insufficient for measuring the extent that a community may be considered "safe." Other important qualities of community safety include rates of violent crimes committed by and against Aboriginal people, the state of violence against Aboriginal women and the accessibility of crime prevention and rehabilitation programs for both victims and offenders. Most importantly, however, the views of community members themselves about the level of violence and victimization they experience provide important markers for the overall safety of a community.

Rationale

The Community Safety indicator aims to measure community safety on two levels of analysis. First, it measures incarceration rates and rates of violent crimes. This measurement is an important marker of the changing socio-economic conditions across Aboriginal and northern communities. Second, Community Safety aims to measure the extent that culturally appropriate forms of justice and healing are available to community members. The Government of Canada is already taking action to meet this need. For example, through the Aboriginal Justice Strategy and in partnership with the provinces and territories, Canada provides funding to 451 communities for community-based justice and other programs that reflect the particular cultural values of participants.[Note 44] Measuring diverse aspects of Community Safety enables programs who deliver related services to assess how their programs are working to meet the needs of specific communities. We propose that programs focus on the following measures for assessing community safety.

Headline Measures

- Rate of incarceration of Aboriginal peoples vs. general population

- Rates of violent crime committed by and on Aboriginal peoples

- Reported perception on safety and fear of crime within the community

setting

- Percentage of crime prevention and rehabilitation programs administered by community members

Other Measures

- Number of crime prevention programs

- Number of crimes and level of criminality in the areas where indigenous

peoples live vs. in areas where there is a mixed population

- Number and participation rates of victim and offender rehabilitation

programs

- Community members' perceptions of the justice system

Assessment

The availability and validity of data for the Community Safety indicator vary between the two levels of analysis. On the one hand, incarceration rates are currently collected by Statistics Canada. The rate is calculated using the number of adults incarcerated based on data from the Integrated Correctional Services Survey (ICSS). Incarceration rates can further be measured against educational attainment and employment status to reveal a larger trend of the socio-economic context from which Aboriginal people come into the judicial system. However, it is important to note that data is not available from all Canadian jurisdictions and determining the proportion of offenders who are from urban centres continues to be a challenge.

The second level of analysis, from which the majority of the suggested measurements arise, are also currently being collected. For example, the 2006 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) collected data on perceptions of safety. However, data related to access and effectiveness to alternative forms of justice and community rehabilitation projects remain limited.

7. Social Support and Community Services

Context

Measures falling under this broad indicator allow us to assess the social environment. Social supports are important to assist individuals in their daily lives, to meet special needs and to respond to community specific and contextual needs. Social supports and community services are integral to the well-being of a population as they help to ameliorate existing health problems and can prevent further health problems from occurring.

In a report published by the province of British Columbia, titled Pathways to Health and Healing, the author notes that traditionally, caring for Aboriginal children was a communal responsibility. Prolonged social and cultural upheaval has jeopardized the ability of the community to provide safe and healthy environments for children. A disproportionate number of children and youth are in government care. When Aboriginal communities face difficulties, they are not always given the resources and supports they need to ensure that children are raised in their home community and culture. "Federal child welfare funding for children living on-reserve is based on children coming into care, rather than on prevention and support for children in the home." [Note 45]

Violence and abuse are also prevalent in many Aboriginal communities. The presence of programs in the community and at school that provide a space for individuals to heal and to come forth with their experiences is a necessary measure of community support.

Rationale

Support from family and the community is associated with better health and well-being. Having programmes in place at the community level to support stresses and conditions arising from poorer socio-economic factors is integral to improving the health of Aboriginal and northern communities.

There are different ways in which we may assess the availability of supports for community and family depending on the needs of the community. The following are potential measures:

- Proportion of First Nations children on-reserve in care

- Number of First Nations children served by day care

- Programs to assist victims of abuse

- Presence of employment training programs

- Programs to heal the legacy of residential schools

- Programs to assist those with a physical or mental disability

Assessment

This indicator confirms the important role that the availability of community resources plays on health and well-being and assesses the social context of health. There are many measures that could be used here targeting the many social supports that are important to the well-being of a community. We have highlighted children in care and abuse because they are two critical issues for Aboriginal communities.

Measures for this indicator must be developed to a greater extent on a situational basis as looking at the presence or availability of programs as a single measure does not necessarily tell us if they are the right programs, if they are being used and if they are serving those communities which are most in need.

While there is some baseline data available across Canada regarding some of these measures (i.e. proportion of children in care), that could serve as useful comparisons for Aboriginal communities, measuring social support and services at the community level is particular to the needs of the community. As such, the indicator may be best developed as a community self-assessment mechanism.

8. Adequate Housing

Context

The Adequate Housing Indicator is strongly linked to indicators for housing quality, durability and safety as outlined in the Thematic Chapter for infrastructure. Housing issues are particularly pressing for the health and well-being of Aboriginal and northern people, particularly for Aboriginal children. An estimated 50% of the urban Aboriginal population under age 15 in Canada inhabits low-income housing.[Note 46]

Similarly, poor health among Métis children has been attributed to inadequate housing.[Note 47] Poor housing quality also contributes to ill health among the adult population. For example, the 2002/2003 First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey found that of the 2.9% of respondents once diagnosed with TB, almost 1 in 3 (31.0%) live in an overcrowded house. It further found that 48.5% of respondents living in band-owned housing reported mold or mildew in their home while only 36.9% of respondents in other types of accommodation reported mold or mildew.[Note 48]

Size and affordability of housing is of concern across communities. Overcrowding effects Aboriginal households at a rate of four to one when compared with the non-aboriginal population.[Note 49] Results from the 2002/2003 RHS [Note 50] found occupant density of First Nation houses at almost double (4.8 persons) that of houses in Canada overall (about 2.6 persons). In the First Nations context, this trend appears to be increasing, while in the non-Aboriginal context the density has been declining over two decades.[Note 51]

Finally, Aboriginal people remain significantly over-represented in the homeless population across Canada. Aboriginal people are at higher risk of homelessness because they experience more profound rates of poverty, unemployment, mental health issues, domestic violence, addictions and sexual abuse than the non-Aboriginal population.

Rationale

Understanding the root causes of homelessness and gaining an accurate picture of homeless and housing trends related to size, affordability and environmental impacts provides programs with important information about the overall health and well-being of Aboriginal communities. In order to adequately measure this complex issue, suggested measures include the following (additional measurements are provided in the Infrastructure Thematic Chapter):

Headline Measures

- Overcrowding (average number of persons/room)

- Rates of disease associated with poor environmental health

- Rates of homelessness

- Number of aboriginal low-income housing units (vacancy rates)

- Percentage of aboriginal and northern people on social housing wait

lists

- Shelter costs to income ratio (housing that costs less than 30 per cent of gross household income)

Other Measures

- Proportion of homes with mold

- Extent that the housing market on-reserve is an economic engine creating value

Assessment

Data for housing is available within the Department and can be applied both provincially and nationally through such sources as the Community Well-being Index (CWB) and Inuit Well-being Index which include dimensions such as labour force participation and employment, income and housing. These indicators are derived from Census data and combined to form a single index score using a similar methodology as that used by the Human Development Index (HDI). Also, the Aboriginal Peoples Survey collects data about levels of satisfaction of housing quality while the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation has a variety of available data tables bringing together information from diverse sources.

However, there is limited quantitative data available to understand some of the drivers of homelessness, particularly in the North. This is primarily due to inconsistencies in defining relative and absolute "homelessness" and the mobility/elusiveness of the population. Some information about shelter use has been made available. The 2001 Census added "shelters" to the type of collective dwelling. This category includes emergency or temporary accommodation for persons who may have no other usual place of residence, facilities for abused women/partners and their children, halfway houses and other shelters with some form of assistance. Measuring homelessness as a sub-indicator presents several challenges and may not be reliable; however, additional information can be obtained using other population statistics to provide a more comprehensive measure of housing need.

9. Literacy and Language Ability

Context