Archived - Evaluation of the Intervention Policy

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: November 2010

Project Number: 09082

PDF Version (488 Kb, 101 Pages)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Note

- Executive Summary

- Management Response/Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Performance (Effectiveness/Success)

- 5. Evaluation Findings - Performance (Efficiency and Economy)

- 6. Evaluation Findings - Design

- 7. Evaluation Findings - Delivery

- 8. Evaluation Findings - Improvements and Alternatives

- 9. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Revised Evaluation Matrix

- Appendix B - Draft Intervention Policy Framework Logic Model

- Appendix C - Remedial Management Plans

- Appendix D - Summary of Data Analysis

- Appendix E - Summary of Statistical Analysis

- Appendix F - Summary of Interviews

- Appendix G - Summary of Case Study Sample

- Appendix H - Data Tables

- Appendix I - Causal Factors Framework

- Appendix J - Potential Indicators

List of Acronyms

Note

Please note the expression "First Nations under Intervention Policy" or "First Nations under a specific level of intervention" applies to intervention in relation to the funding received by First Nations and organizations from INAC.

Executive Summary

Introduction

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) current Intervention Policy was adopted in 2006 and is designed to ensure the ongoing delivery of programs and services, and to maintain accountability while defaults under funding agreements are addressed by recipients (i.e. First Nations, Aboriginal Organizations). Over the long term, application of the policy should lead to improved performance by recipients and a reduction in the number of First Nations that have seen their funding put under intervention policy[Note 1] and in the duration of such intervention.

There are four triggers for intervention: the terms and conditions of the funding agreement are not met by the recipient; the recipient's auditor gives a denial of opinion or an adverse opinion; the recipient has incurred a cumulative operating deficit equivalent to eight percent or more of its annual operating revenues; and the health, safety or welfare of First Nation members is being compromised. There are three main levels of intervention: recipient-managed, co-managed and third party managed.

The objectives of this evaluation are to assess the relevance, success, cost-effectiveness, design and delivery of the Intervention Policy, and to explore improvements to the policy and alternatives to it. At the time of the evaluation, INAC was working on a new Intervention Policy (tentatively named the Default Prevention and Management Policy). This new policy is seeking to be more aligned with INAC's new orientation and tools regarding capacity development with a focus on prevention and ongoing sustainability. This evaluation is also expected to inform the development of the new policy.

Methodology

Six lines of evidence informed the evaluation:

- A literature review.

- A document and file review.

- A data analysis of INAC's performance and financial data.

- Key informant interviews with INAC regional and Headquarter officials, other key federal departments and key people from other organizations; as well as a select number of First Nations and other Indian-administered organizations, third party managers, co-managers and funding services officers for the case studies. A total of 85 interviews were conducted with individuals or groups of individuals by phone, teleconference or during site visits for the case studies.

- Case studies of 24 First Nations and three other Indian-administered organizations. The case studies were designed to be broadly representative of the statistics on intervention as well as other variables, such as regions, remoteness, size and community well-being. They included successful and less successful recipients.

- Subject expert panel to review the evaluation approach and preliminary findings and conclusions.

The evaluation was conducted from January to June 2010 and included site visits to five regions, video conferences with two regions, and telephone interviews with two regions. The evaluation report was revised by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) based on the findings of research conducted by the consulting firm Institute On Governance and EPMRB.

Evaluation Findings

The Intervention Policy Continues to be Relevant:

The evaluation demonstrates that the Intervention Policy remains relevant and there is a continued need to protect funding for programs and services, to ensure the delivery of essential services, and to ensure accountability for how federal monies are spent. There is also a continued need to build the capacity of recipients to manage and administer funds. The Intervention Policy is consistent with federal government and INAC plans and priorities, and the federal government's roles and responsibilities. INAC's Intervention Policy has been used as the basis for the intervention policies of Health Canada (HC) and the First Nations Financial Management Board (FNFMB); and INAC, HC and FNFMB are working together to coordinate changes to the policy.

The Intervention Policy Has Had Mixed Success in Achieving its Objectives:

There has been a modest reduction in the number of recipients under intervention, particularly in the last few years. There has also been a reduction in the number of recipients with a cumulative operating deficit of eight percent or higher. The Intervention Policy has been successful in ensuring the ongoing delivery of essential services, maintaining the health and safety of band members, and ensuring the external accountability of recipients to INAC.

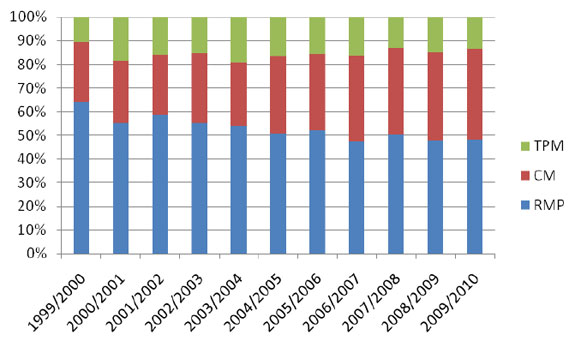

On the other hand, the level of intervention has not decreased – in fact, an increasing proportion of First Nations are under co-management and a decreasing proportion of First Nations are under recipient managed intervention over the past ten years. Also, a number of First Nations that have been under some form of intervention policy for a long period of time – for example, 42 percent of First Nations under some form of intervention as of March 31, 2010, had been under intervention for ten or more years.

Any changes in the incidence, level and duration of intervention cannot necessarily be attributed solely to the implementation of the policy since other factors, such as access to own source revenue, economic performance in certain sectors, or the supply of credit can also have an impact. The major deficiency under the policy identified by the evaluation is capacity building.

A Number of Factors Affect the Success of the Intervention Policy:

There are a number of underlying factors related to governance, management, community engagement and funding practices that affect the success of the Intervention Policy. There are also a number of contextual factors related to community endowments (natural resources, geographic location, economic opportunities and access to own source revenue, the strength of the private sector, population size and growth); community member endowments (education, health, cultural identity); and social cohesion and security that could affect the success of the policy. Many of these factors are outside of the control of the Intervention Policy.

The key success factors identified by the evaluation are: willing and committed leadership in recipients, stable and competent management, community engagement, positive external relationships, and access to significant own source revenue.

The Intervention Policy is not Cost-Effective:

Considerable time and effort is required from INAC and recipients to implement the Intervention Policy. The cost of co-managers and third party managers affects the availability of band support funding for governance and administration in recipients. Third party managers are not able to use surpluses to pay off debt. Any improvements in the results of intervention as well as other interventions outside of the policy to address willingness, capacity and low own source revenue should increase cost-effectiveness.

The Intervention Policy is not Well Designed to Achieve all of its Objectives:

The major gaps in the design of the Intervention Policy identified by the evaluation are: a capacity development framework, prevention strategies, and common assessment tools. Some key informants suggested that INAC provide additional funding for co-managers and third party managers in order to increase the willingness of recipients, enhance recipients' capacity, and improve INAC's ability to monitor. Some key informants also suggested that alternative debt retirement tools are needed for recipients with little access to own source revenue.

INAC's Intervention Policy is Similar to Other Intervention Approaches:

INAC's Intervention Policy is similar to provincial government approaches to their subnational entities (municipalities, school boards and hospitals) and to other countries' approach to Aboriginal recipients in terms of objectives, triggers, levels of intervention and remedies, and oversight and monitoring. The key differences are that provincial governments are better able to control the debt of their subnational entities under a legislative framework, and that some of the other approaches provide more capacity building support through a broader range of capacity building mechanisms.

The Intervention Policy is Being Implemented as Planned, With Some Gaps in Monitoring and Support:

The Intervention Policy provides a common framework for the objectives, triggers, assessment, and levels of intervention, and INAC's regional offices are adhering to the required procedures. There are, however, variations within and between regions, primarily in terms of the capacity of recipients and INAC funding service officers. Key informants suggested that capacity be strengthened with training and other tools related to the Intervention Policy. Other suggested improvements are: increased monitoring by INAC of the performance of co-managers and third party managers; changes to the information collected in First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment (FNITP); and more formalized processes for communication and sharing of information with other government departments.

Suggested Improvements and Alternatives

The main suggested improvements to the Intervention Policy are:

- Improved prevention and early detection linked to the general assessment of recipients that will be conducted annually;

- Revision to the trigger on debt to better reflect different aspects of the financial health of recipients;

- A broader range of tools and mechanisms for assessing and addressing the capacity building requirements of recipients, and additional dedicated funding for this purpose; and

- Simplifying the recipient-managed level of intervention; strengthening the co-managed level; and supplementing third party management with other capacity building initiatives, separately contracted and funded.

Other alternatives were suggested to deal with issues that are outside of the influence of the Intervention Policy but have an effect on its success. These issues include: increased leadership stability and community engagement, improved funding practices or a modified funding regime, and alternative debt management approaches.

It is recommended that INAC:

- Implement prevention and early detection strategies to prevent First Nations going into intervention status or escalating to a more serious level of intervention. Activities should include:

- Better identification of financial and governance capacity gaps and needs (linked to the general assessment);

- Better and broader identification of triggers for third party management and co-management;

- Identification of incentives for third party managers to build First Nations capacity, to be written into agreements with third party managers;

- Development of questions to assess properly key success factors to analyze trends in relation to escalation and de-escalation (consider undertaking community surveys to better assess community capacity factors for success); and

- Improve communication and coordination at the national and regional level with other federal government who deliver services and programs to First Nations.

- Better identification of financial and governance capacity gaps and needs (linked to the general assessment);

- It is recommended that:

- Third party managers be prequalified and assessed against performance criteria;

- INAC audit co-management and third party management arrangement on a risk basis; and

- Revise the third party management agreement to request participation of third party managers in evaluations as well as in audits.

- Third party managers be prequalified and assessed against performance criteria;

- The proposed new Default Prevention and Management Policy should address the design and delivery gaps of the current Intervention policy by:

- Implementing national tools and formalized processes in the assessment of First Nations;

- Clarifying FSO roles and responsibilities, developing job descriptions that identify competencies and knowledge needed, and identifying training to meet requirements; and

- Clearly communicate the new policy and assessment processes to stakeholders and First Nations.

- Implementing national tools and formalized processes in the assessment of First Nations;

- Develop and implement better monitoring and reporting systems that involve:

- A performance measurement strategy to allow for meaningful reporting through quarterly progress reports and the Departmental Performance Report. Indicators such as duration, incidence and level of intervention, and level of implementation of Remedial Management Plan could be considered;

- A cost tracking system at the Headquarters and regional level to capture cost data in order to measure cost effectiveness and inform future decisions; and

- Re-design the intervention policy module in FNITP that will involve a revision of the inputs, processing and output (reports) of the system at the regional and national level in order to make it more user-friendly, reliable and to inform performance measurement strategy to be developed in line with the new policy.

- A performance measurement strategy to allow for meaningful reporting through quarterly progress reports and the Departmental Performance Report. Indicators such as duration, incidence and level of intervention, and level of implementation of Remedial Management Plan could be considered;

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Intervention Policy

Project #: 09082

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Implement prevention and early detection strategies to prevent First Nations going into intervention status or escalating to a more serious level of intervention. Activities should include: a. Better identification of financial and governance capacity gaps and needs (linked to the General Assessment); |

a. The roll out of the General Assessment (GA) tool got underway in October 2010 and will be fully implemented by April 1st, 2011. The GA will provide information as to the risk level of recipients and will also serve to identify recipients' capacity gaps. The GA will be used as a source of information to prevent and address defaults under a new Default Prevention Management Policy. | CFO/RO - Director of Operations and Implementation and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | From April, 2011 |

| Regional Operations Sector is currently in the process of developing two more effective approaches to capacity development programming within INAC and will develop strategies to better respond to gaps identified in the GA. | RO - Director General of Governance Branch and Director of Sustainable Communities | 2011-12 | |

| b. Better and broader identification of triggers for third party management and co-management; | b. The new Default Assessment Tool will add consistency to the decision to appoint a Third-Party Funding Agreement Manager (TPFAM). This tool will be based on concrete evidence provided from a number of sources such as field visits, the GA and other available information. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | 2011-12 |

| c. Identification of incentives for third party managers to build First Nations capacity, to be written into agreements with third party managers; | c. It is often found that the relationship between the TPFAM and the recipient is not amenable to building trust and capacity. As a result, incentives are not written into the funding agreements. However, upon re-opening the MERX process identifying a new set of TPFAMs, the need to include incentives and milestones for capacity development will be evaluated. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | 2011-12 |

| d. Development of questions to assess properly key success factors to analyze trends in relation to escalation and de-escalation (consider undertaking community surveys to better assess community capacity factors for success); and | d. The Policy on Transfer Payments identified key capacity requirements for success (governance, organizational capacity, mature processes / procedures, accountability mechanisms, and financial health). The Department is developing assessment tools to examine recent strengths and weaknesses related to these capacity requirements. The General Assessment and Readiness Assessment are key tools under implementation and development now. The processes and structures around these tools involve purposeful, focused community engagement. In addition, the Department is examining options for more comprehensive approaches to supporting community development and community planning, which will further strengthen our understanding of community key success factors. The results of the GA will be reviewed annually to monitor escalation or de-escalation of all communities/recipients in various areas and key factors to generate escalation will be explored. |

CFO – Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise, RO – DG OPS Branch and DG Governance Branch. | 2011-12 |

| e. Improve communication and coordination at the national and regional level with other federal government who deliver services and programs to First Nations. | e. Work with DOJ and other federal departments to facilitate information sharing between federal departments where there is a common recipient e.g. working with Health Canada on a protocol and common agreement clauses and look for opportunities for harmonization in regards to community development. INAC also co-ordinates an ADM Network on Aboriginal Affairs that meets regularly to improve communication and coordination. Regional managers participate in Federal Regional Councils. |

RO / CFO - Director of Operations and Implementation and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | Ongoing |

| 2. It is recommended that: a. Third party managers be prequalified and assessed against performance criteria; |

a. The current third party managers' prequalified list was established in FY 2009-10 by means of a MERX competitive process. The list as well as Framework Agreements with third party managers are valid for a period of three years and can be amended for a period up to five years. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | Completed |

| The current Intervention policy requires that a performance review be conducted to assess the performance of the third party manager in meeting the requirements of the third party management agreement. CFO is currently reviewing the Policy and will ensure performance review requirements continue to be addressed in the new Default Prevention Management Policy by means of improved monitoring tools. | 2011-12 | ||

| b. INAC audit co-management and third party management arrangement on a risk basis; and | b. CFO will ensure that its revised directive on third party management requires sectors to perform audits of co-management and third party management agreements on a risk basis. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | 2011-12 |

| c. Revise the third party management agreement to request participation of third party managers in evaluations as well as in audits. | c. The current third party framework agreements already include an audit clause that requires third party managers to provide all necessary assistance to auditors. CFO will ensure that new framework agreements include a requirement for participation of third party managers in evaluation as well. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | Completed |

| 3. The proposed new Default Prevention and Management Policy should address the design and delivery gaps of the current Intervention policy by: a. Implementing national tools and formalized processes in the assessment of First Nations; |

a. Policies/directives for default management and the GA as well as tools supporting consistency and implementation will be formalized through a national process in First Nation Inuit Transfer Payment. | RO / CFO - Director of Operations and Implementation and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | April 2011 |

| b. Clarifying FSO roles and responsibilities, developing job descriptions that identify competencies and knowledge needed, and identifying training to meet requirements; and | b. Roles and responsibilities will be clearly identified in the policy/directives document. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | April 2011 |

| FSO roles are currently being reviewed to identify requirements for strategic alignment with core functions. A report has already been tabled and is currently being considered in term of realigning resources to operational priorities. | RO - Deputy Minister's Special Representative on Reduced Reporting | April 2011 | |

| c. Clearly communicate the new policy and assessment processes to stakeholders and First Nations. | c. Engagement sessions on the new Default Prevention and Management Policy were delivered over summer 2010. Policy-directives document will be reviewed based on feedback from those sessions. Training-info sessions will be provided to INAC staff before and after April 2011 implementation. INAC will liaise with AFOA in order to update Aboriginal training material provided by AFOA to Aboriginal recipients. | CFO - Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | July 2011 |

| 4. Develop and implement better monitoring and reporting systems that involve: a. A performance measurement strategy to allow for meaningful reporting through quarterly progress reports and the Departmental Performance Report. Indicators such as duration, incidence and level of intervention, and level of implementation of Remedial Management Plan could be considered; |

a. CFO will report quarterly to the Financial Management Committee Senior Management meeting, on the intervention status, based on clear indicators. National oversight will also be managed annually by Operations Committee to review all communities with default management activity. | RO / CFO - Director of Operations and Implementation and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | April 2011 |

| b. A cost tracking system at the headquarters and regional level to capture cost data in order to measure cost effectiveness and inform future decisions; and | b. Cost of 3rd party managers will be tracked in FNITP and oversight reports will be regularly produced. | CIO / CFO - CIO, Manager IPCSD and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | 2011-12 |

| A one time assessment of costs other than 3rd party management will be performed after two years of application of the new policy to measure the cost effectiveness. | RO / CFO - Director of Operations and Implementation and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | 2013-14 | |

| c. Re-design the intervention policy module in FNITP that will involve a revision of the inputs, processing and output (reports) of the system at the regional and national level in order to make it more user-friendly, reliable and to inform performance measurement strategy to be developed in line with the new policy. | c. The FNITP intervention module will be redesigned to align with the new Default Prevention and Management Policy and its underlying directives. | CIO / CFO - CIO, Manager IPCSD and Senior Director of Transfer Payments Centre of Expertise | 2011-12 |

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of the Intervention Policy were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on November 18, 2010.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The purpose of the evaluation is to assess the relevance, design, delivery, success and cost-effectiveness of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Intervention Policy and to look at best practices, improvements and possible alternatives. The evaluation report provides information on the policy, the methodology that was used in the evaluation, the findings and conclusions for each of the evaluation questions, and overall conclusions and recommendations.

1.2 Policy Profile

1.2.1 Background

INAC's Intervention Policy is an internal financial management policy that has evolved over time to deal with various issues such as indebtedness, remedial management plans, and third party management. The current policy was developed partly in response to a 2003 audit by the Auditor General of Canada of the implementation of third party management; and partly, as a result of a comprehensive legal review to reduce Crown exposure to liabilities.

The policy was introduced in December 2006 and came into effect on April 1, 2007. It is issued under the authority of INAC's Chief Financial Officer. It consolidates all previously existing intervention practices under a single policy.

At the same time as the Intervention Policy was adopted, a Companion Initiative to develop the capacity of recipients under Intervention Policy was introduced. The objective of the Companion Initiative was "to support short term, high impact initiatives that will make a measurable difference."[Note 2] It was funded for 2006/07 and 2007/08 under the authority of the Indian and Inuit Management Development transfer payment authority after which time it was to be included in a renewed authority.[Note 3]

At the time of the evaluation, INAC was working on a new Intervention Policy (tentatively named the Default Prevention and Management Policy) as some elements were considered not addressed by the 2006 Intervention Policy. This new policy is seeking to be more aligned with INAC's new orientation and tools regarding capacity development with a focus on prevention and ongoing sustainability. To assist the Department in the development of this new policy, the Department seeking for the advice of experts in financial management, including advice from the First Nations Financial Management Board, the Aboriginal Financial Officers Association and the Assembly of First Nations through consultation and engagement session. Engagement sessions with stakeholders and regional staff will be held over the summer 2010 with the goal of having a new policy in place for the beginning of fiscal year 2011-2012. This evaluation is expected to inform the development of the new policy.

1.2.2 Policy Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The purpose of the Intervention Policy is to permit the delivery of programs and services and maintain accountability while problem situations are being addressed; and to put the onus on the recipient to correct the problem situations. The policy is also designed to support timely intervention and consistency in regional operations; to facilitate ongoing monitoring of intervention; and to improve the effectiveness of intervention. The aim of the policy is to encourage the recipient in default to enhance their capacity to provide programs and services, and to provide for an exit strategy where a lesser or no form of intervention is required.[Note 5]

1.2.3 Policy Framework

The Intervention Policy sets out a framework for intervention by the Minister in the event that a recipient defaults under the terms and conditions of a funding arrangement. It applies to all funding arrangements except legislated self-government agreements. It includes the triggers for intervention, the levels of intervention, the process, roles and responsibilities, performance review, accountability framework (for third party managers), and exit strategy.

There are four triggers for intervention for use with First Nations and tribal councils:

- the terms and conditions of the funding agreement are not met by the recipient;

- the recipient's auditor gives a denial of opinion or adverse opinion with respect to the recipient's financial statements;

- the recipient has incurred a cumulative operating deficit equivalent to eight percent or more of its total annual operating revenues; and

- the health, safety or welfare of First Nation members is being compromised.

The Intervention Policy does not apply to election disputes and allegations and complaints except where an election dispute or concern raised gives rise to a default. If the recipient is a corporation, bankruptcy, insolvency or liquidation can also lead to intervention.

According to the policy, in the event of a default, INAC notifies the recipient, undertakes an assessment of the recipient's capacity and willingness to address the default, and determines the level of intervention required. There are three main levels of intervention:

- Recipient-managed level – a low level intervention when the recipient is willing and has the capacity to address the default based on a Remedial Management Plan (RMP).

- Co-managed level – a moderate level intervention when the recipient is willing but lacks the capacity to address the default. The Council of the First Nation or Tribal Council is required to enter into a co-management agreement with a co-manager in addition to developing or amending and implementing a RMP.

- Third party managed level – a high level intervention when INAC determines that there is a high risk to the funding provided under a funding arrangement or to the provision of programs and services, or that the council is unwilling to address the default. INAC then appoints a third party manager to administer its funding. Third party management is also used in a situation where no funding arrangement has been signed by the council.

INAC may also withhold funds, terminate the funding agreement, take any other reasonable action, or require any other reasonable action to be taken by the recipient.

According to the policy, RMPs are developed and implemented by the recipient. They are approved by the Council of the First Nation or tribal council (or the appropriate authority for other entities) and by the Regional Director of Funding Services, and are attached to the funding arrangement. RMPs should include the following elements:

- The purpose of the RMP;

- The effective date;

- A description of the causes that resulted in intervention;

- The corrective action to be undertaken within specific time frames to address the causes;

- Performance indicators that will be used to measure the effectiveness of the corrective action;

- The roles and responsibilities of the parties to the RMP;

- In cases where financial difficulties have resulted in intervention, a financial projection of the estimated consolidated revenue and expenditures and a debt management plan;

- Capacity building or training to be undertaken to strengthen the recipient's capacity to implement corrective action;

- A reporting and monitoring clause;

- A provision for amendments to the plan; and

- A provision for an intervention exit strategy.

At the co-management level, the council selects and contracts a co-manager. The role of a co-manager is to assist the council in remedying the default, developing sound management practices, restoring financial health, and building capacity. The co-manager is to be given financial signing authority for all accounts containing INAC funding. The council pays for the co-manager's services, usually from its Band Support Grant.

At the third party management level, INAC selects the third party managers from a pre-qualified list of individuals or firms and negotiates a third party agreement (see Section 7.1). All INAC funding, or funding for a particular program or service, is redirected to the third party manager to administer. INAC may also require that the third party manager assist the council in enhancing capacity to administer funding in order to remediate the default that gave rise to the intervention. The third party manager is required to maintain a system of accountability to the community in terms of the programs and services that are funded under the third party management agreement. The third party manager's services are normally paid from the INAC's Band Support Grant.

Councils are responsible for their credit transactions and any debt they may have incurred. The Crown is not obligated to pay or accept responsibility for any current or future debt. Employees remain the responsibility of the council but the third party manager determines which of the council's operational and administrative staff are necessary for the continuation of programs and services, and pays the salaries and benefits of those staff from INAC funding.

According to the policy, INAC monitors the progress of the intervention at least quarterly. Where possible, the council is included in the review of the performance of the third party manager. Based on the monitoring, INAC may decide to escalate or de-escalate the level of intervention or terminate it. In the event that co-management or third party management is being de-escalated or terminated, the council is required to develop an administrative transition plan for the transfer of full authority back to the council.

1.2.4 Policy Management

The Chief Financial Officer Sector manages the Intervention Policy and the regions implement the policy. According to the policy, INAC Headquarters is responsible for:

- ensuring consistency across the regions;

- providing direction and training on the application of the policy;

- strengthening management processes in support of the policy;

- ensuring that plans are monitored and performance reviews are undertaken;

- ensuring that the transfer of responsibility back to the funding recipient is done as soon as practical;

- providing for the periodic review of regional compliance and implementation of the policy; and

- periodically reviewing and revising the policy with input from recipients.

INAC regional offices are responsible for:

- identifying potential intervention situations;

- implementing the intervention process;

- approving the level of intervention;

- notifying other federal government departments if a third party manager is appointed;

- assessing and approving RMPs:

- assessing capacity deficiencies;

- appointing third party managers from the approved list;

- operating systems and procedures for implementation;

- maintaining proper documentation and files; and

- updating the intervention module in the First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment System (FNITP).

1.2.5 Policy Resources

The Intervention Policy is issued under the authority of the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and no specific funds are currently targeted to this policy. Funding in support of the development of the policy is included in the CFO's A-base budget. Funding for regional implementation of the policy is included in regional A-base budgets. All fees related to services provided by a co-manager or a third party manager are the responsibility of the council and are normally drawn from the Band Support Grant provided to the council by INAC.

The Companion Initiative on Capacity Development was funded in fiscal years 2006-2007 (starting January 2007) and 2007-2008 using Budget 2006 funds authorized by the Treasury Board. Treasury Board approved $10.6 million. Seventy-five percent of the funding was allocated to the regions on the basis of the average regional distribution of required interventions over the past three years, and the remaining 25 percent of funding was allocated on the basis of regional population. Other funds (about $500,000) were available for tribal councils and other institutions, such as regional Aboriginal Financial Official Officers Association (AFOA) Chapters to provide support.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Objectives

In accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Evaluation Policy, the evaluation examines issues related to relevance, success and performance. Design and delivery issues are also assessed to guide and improve the policy and performance measurement efforts. Best practices, improvements and alternatives are also explored. Terms of Reference were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on September 24, 2009.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The following broad evaluation issues guide the evaluation:

- Relevance

Evaluation of relevance looks at the extent to which the Intervention Policy addresses existing needs and priorities; is consistent with federal priorities, roles and responsibilities; and does not duplicate or overlap with the policies of other stakeholders.

- Success

Evaluation of success looks at whether the Intervention Policy objectives are being achieved and what factors have facilitated or hindered the achievement of the policy objectives. It also looks at the underlying causes and key success factors, as well as the unintended, positive or negative, impacts of the policy.

- Cost-Effectiveness

Measuring cost-effectiveness of the Intervention Policy involves identifying the cost of intervention in relation to the outcomes and comparing it to the cost of other intervention approaches (of other First Nation and tribal council funders in Canada, of provincial governments, and of other countries).

- Design

Evaluation of the design of the Intervention Policy looks at whether the policy is well designed to achieve its objectives and how it compares to the design of other intervention approaches.

- Delivery

Evaluation of the delivery of the Intervention Policy complements the work already done by the Audit of the Application of the Intervention Policy (2009) by looking at whether the policy is being implemented as planned, whether good guidance and monitoring is in place, what constraints impede implementation, and what are the best practices.

- Alternatives

Finally, the evaluation looks at the alternatives to the Intervention Policy to achieve the same results or to improve the results. In particular, the evaluation examines other models of intervention used by other funders of First Nations and tribal councils in Canada, by provincial governments, or by other countries.

The evaluation questions related to each of these issues can be found in Appendix B, Revised Evaluation Matrix.

2.3 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examines Intervention Policy activities undertaken since its adoption in December 2006 and up to March 31, 2010. Because the Intervention Policy has never been evaluated, however, historical information over the past ten years or more have been looked, drawing from INAC's financial information systems, previous audit data and key informants. This helps us to place recent activities into an historical context and identify any overall trends.

INAC is in the process of reviewing and revising the 2006 Intervention Policy. While the evaluation team received documentation related to the revised Intervention Policy, it has not been included in the analysis because it has not been finalized. Our focus is therefore on the current Intervention Policy.

The relevance, design, delivery, success and cost-effectiveness of the Intervention Policy were assessed through qualitative and quantitative data; and triangulate the information across a number of sources. In order to assess what may have affected the achievement of the outcomes of the policy and make recommendations for changes or alternatives, possible underlying causes, preventive measures, and exit strategies were explored.

The evaluation takes into consideration previous audits, other evaluations, reports on the Intervention Policy and the Companion Initiative, and other relevant documents. It also takes into account other related INAC policies on community development, transfer payments, risk assessment, capacity building, and funding arrangements.

The perspectives of various INAC officials as well as the recipients in the evaluation were solicited. Information from the Chief Financial Officer Sector and the Regional Operations Sector, as well as from all INAC regions, except Nunavut, were collected.[Note 6] Information from a range of First Nations, tribal councils and other Aboriginal organizations was also collected. Finally, the intervention approaches of other key federal departments, other jurisdictions, and other countries, as well as the perspectives of subject matter experts who have a knowledge and interest in the evaluation issues were examined.

The evaluation was conducted from January to June 2010. It was preceded by a pre-consultation phase conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB), which led to the development of a draft Evaluation Methodology Report and draft Logic Model. From January to March 2010, the Institute On Governance (IOG) finalized the Evaluation Methodology Report and developed the data collection instruments; drafted the Document Review; and conducted the Literature Review. From April to June 2010, IOG made site visits with the assistance of EPMRB to five of the regions (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan) and conducted the case studies and interviews. EPMRB also compiled and analyzed data during this period. Two subject expert panel meetings were held by IOG with EPMRB participation – one at the end of the planning phase and one at the end of the data collection phase. Preliminary findings and conclusions were presented by IOG to INAC senior management at the end of May 2010. EPMRB developed the recommendation based on the report submitted.

2.4 Evaluation Methodology

2.4.1 Development of a Framework Logic Model

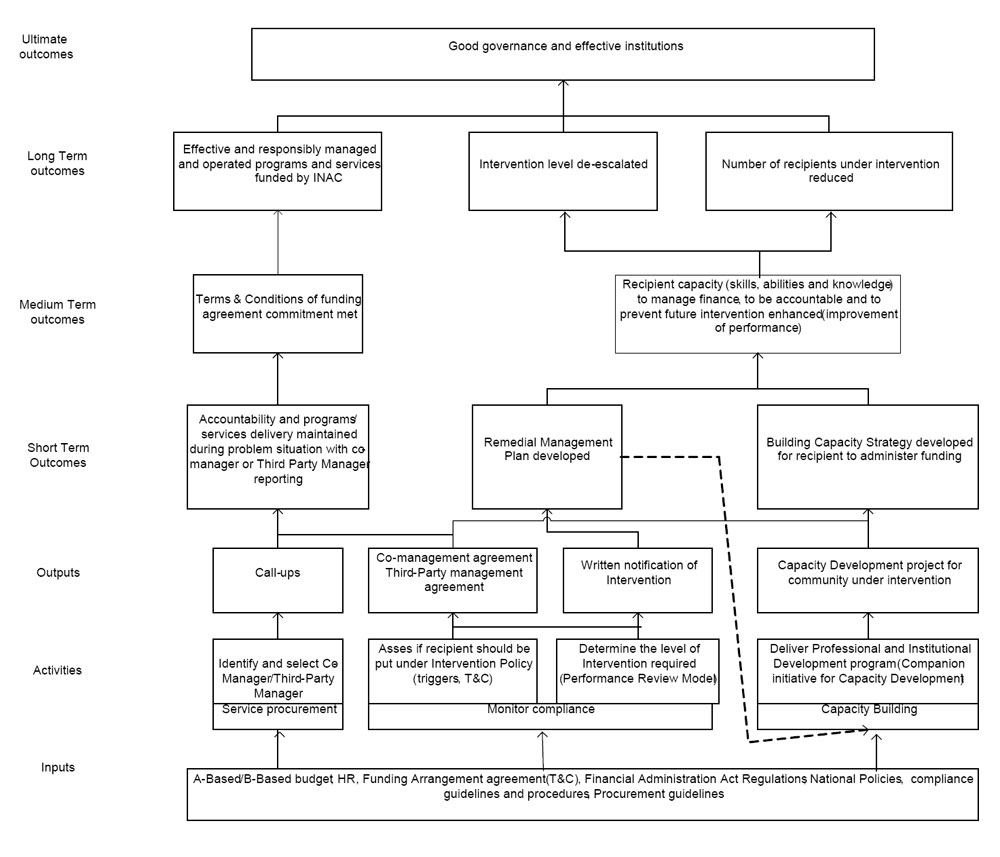

EPMRB developed a draft Framework Logic Model for the Intervention Policy based on the purpose, aims and objectives of the policy; pre-consultations with key informants in INAC; and INAC's Strategic Outcomes (Appendix C, Draft Intervention Policy Framework Logic Model). The draft Logic Model was used by EPMRB to help clarify the evaluation issues and the short, medium and long-term outcomes.

According to the draft Logic Model, INAC carries out a number of activities in order to ensure that services are delivered and accountability is maintained, remedial measures are implemented, and recipient capacity is strengthened. In the long term, this should lead to improved performance and ultimately the de-escalation of intervention and earlier exit from intervention; a reduction in the number of First Nations that have seen under intervention and the duration of such intervention; and effective and responsibly managed and operated programs and services funded by INAC. The evaluation questions and the evaluation methodology were designed to measure the achievement of these outcomes.

2.4.2 Data Sources

The evaluation methodology incorporates six lines of evidence: a literature review, a document and file review, data analysis, key informant interviews, case studies, and a subject expert panel. The subsequent sections provide a summary of each of these lines of evidence. The Revised Evaluation Matrix (Appendix B) indicates which line of evidence was used to answer each of the evaluation questions.

1. Literature Review

The purpose of the literature review was to define and explore the key issues related to intervention by one level of government of another level of government, or by a funder to a recipient organization. The literature review has informed the findings and conclusions in this evaluation report, particularly related to design, delivery and effectiveness, as well as potential alternatives.

The literature review includes a brief survey of public policy and administration and social science, academic journal databases using key words like intervention, default, debt management, remedial management, third party management, supervision, trusteeship ("mettre en tutelle" in French) and remediation. As a result of the survey, three key lines of inquiry emerged as being most relevant to INAC's Intervention Policy – systemic intervention, intervention in distressed states and communities, and intervention in subnational entities.

Eight Canadian and international intervention examples were initially selected for further investigation, and another example of an alternative approach was identified during the data collection phase. The examples were used to illustrate the various approaches that have been taken to intervention and include:

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada;

- First Nations Financial Management Board;

- the Government of British Columbia and its municipalities;

- the Government of Ontario and its school boards;

- the Government of Ontario and its public hospitals;

- the U.S. Federal Government and American Indian Tribal Governments;

- the Commonwealth of Australia Government and Australian indigenous corporations;

- the Queensland State Government and indigenous councils in Queensland, Australia; and

- an alternative approach involving a number of federal and territorial government departments in an isolated community in Nunavut.

IOG gathered information on the other intervention approaches from government publications and other reports, and interviewed key informants for six of the examples.

The literature review concludes with a summary of the issues, lessons learned and potential alternatives.

2. Document and File Review

EPMRB identified relevant files and documents during the preliminary consultation phase of the evaluation and IOG supplemented them during the data collection phase. These documents included audits, evaluations, and policy documents on the Intervention Policy and related policies. IOG also conducted a Google search of media reporting on INAC's intervention over the past five years.

EPMRB asked INAC's regional offices to provide samples of RMPs for five recipients under remedial management and five recipients under co-management or third party management and were reviewed by IOG. All regions except the Northwest Territories (NWT) region provided a sample that covered a total of 63 First Nations, two Indian-administered organizations, two co-managers, and two third party managers. A summary of the sample of RMPs is provided in Appendix D.

The document and file review provided a background briefing for the evaluation team prior to the data collection phase and informed the findings for a number of the evaluation issues and questions.

3. Data Analysis

In collaboration with EPMRB, IOG conducted an analysis of INAC's performance and financial data related to the Intervention Policy from 1999/2000 to 2009/2010. EPMRB compiled a database for analysis, drawing from existing INAC management systems, financial systems and other relevant databases. EPMRB also cleaned the data and validated the data on intervention over the past 11 years with INAC's regional offices. PASW Statistics 18[Note 7] software was used by EPMRB for the analysis and EPMRB worked with INAC's Research and Analysis Directorate to integrate and analyze data on the Community Well-being (CWB) Index.

The databases and sources of information used in the analysis were:

- First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment System for financial information and audit opinion;

- Regional offices for intervention level data validation and third party managers (TPM) costs;

- Band Governance – Regional Operations for election system data;

- Research and Analysis Directorate for registered population data and the CWB Index; and

- Band Classification Manual for geographic zone data.

The purpose of the data analysis was to provide a description of the application of the intervention policy and to assess quantitative information on its underlying causes or impacts. This includes indicators and trends at a national and regional level related to: the incidence of intervention, the level of intervention, the duration, and the triggers. It also includes variables that may be related to underlying causes including: size, population, remoteness and the CWB Index. Where possible, EPMRB correlated the data on intervention with the data on underlying causes and interpreted the results.

Because the total number of Indian-administered organizations under intervention in any year is very small in comparison to the total number of First Nations under intervention, the data analysis for these organizations was limited to the incidence and level of intervention.

Appendix E – Summary of Data Analysis provides a summary of what was originally planned and what was actually achieved in terms of the data analysis. Appendix F provides the type of analysis that was conducted. We have incorporated relevant results into this Evaluation Report.

4. Key Informant Interviews

IOG conducted a number of interviews with INAC regional office and Headquarter managers, other key federal departments, and key informants from other organizations. We also interviewed a select number of First Nations and other Indian-administered organizations, third party managers, co-managers and funding service officers as part of the case studies. A total of 122 interviews with individuals or groups of individuals were planned, and a total of 82 interviews or 67 percent were actually conducted (Appendix G - Summary of Key Interviews). The interviews were conducted from April to June 2010.

The interviews were based on interview guides linked to the evaluation issues and questions. They were conducted in person, by phone or by teleconference. The results were written up and provided in the Key Informant Interviews Technical Report and incorporated into this evaluation report.

5. Case Studies

IOG conducted a total of 27 case studies covering all regions except the North. The cases include 24 First Nations and three other Indian-administered organizations. IOG and EPMRB selected the case studies to be broadly representative of the statistics on intervention over the past ten years, as well as other variables such as remoteness, size and community well-being. We consulted with INAC's regional offices about the cases selected and made a few changes due to limitations in accessing recipients or to INAC's funding.

The First Nation case studies cover:

- Three Success Cases - First Nations that have never been under intervention and yet, appear to be disadvantaged in terms of their isolation, low own source revenue, or community well-being.

- Seven Other Success Cases - First Nations that were under intervention for more than five years but managed to exit and have stayed out for two or more years.

- Five Chronic Recipient-Managed Cases – First Nations that have been under recipient-managed intervention for five or more years.

- Nine Chronic Co-Managed or Third Party Managed Cases – First Nations that have been under co-management and/or third party management for five or more years.

The other Indian administered organizations include a tribal council, a child and family services agency, and an education authority. A breakdown of the cases by region is provided in Appendix H - Summary of Case Study Sample.

The case studies addressed a number of the evaluation issues and questions, particularly underlying causes, delivery, and success. In particular, the evaluation team used the First Nation success and other success cases to analyze key success factors; the First Nation chronic recipient-managed and chronic co-managed and third party managed cases to analyze constraints to implementation; and the other Indian-administered organizations cases to analyze how the situation in a First Nation affects its service delivery organization or vice versa.

The case studies were conducted through a documentation review; a site visit where time and resources permitted; and interviews with the recipient, the relevant INAC funding service officer, and co-managers or third party managers, if applicable and where possible. EPMRB sent out an email or letter to the Chief and council, band manager, and co-manager or third party manager for each of the First Nations, and to the Executive Director for each of the other Indian-administered organizations, inviting them to participate in the evaluation. The IOG followed up through email and telephone with all of the contact persons in order to set up a site visit or a telephone interview. The contact person identified other relevant people to include in the interviews. As indicated in Section 2.4.3 Limitations, the evaluation team was only able to conduct interviews with about half of the recipients, three co-managers and one third party manager despite repeated follow-up. Appendix H indicates which cases included interviews with recipients.

6. Subject Expert Panel

IOG convened a subject expert panel of four members and facilitated two half-day workshops. Panel members were individuals with senior experience in INAC and Health Canada, in financial management, governance, and capacity building. IOG also invited members of the advisory committee to attend the workshops.

IOG held one workshop at the outset of the evaluation to review the key lines of inquiry and possible alternatives; and one workshop at the end of the data collection phase to review preliminary findings and conclusions. EPMRB participated to both workshops.

2.4.3 Limitations and Constraints

During the course of the evaluation, the evaluation team faced a number of constraints that limit the reliability of the data and the interpretation of the results. These limitations are presented below in terms of what the issue was, what efforts were taken to mitigate the impact, and how the issue ultimately affected the evaluation. Overall, the evaluation team attempted to address the limitations by using information from all of the data sources; complementing quantitative data with qualitative data; and incorporating different perspectives from the range of key informants and the subject expert panel. We have also qualified the findings where there are issues of data reliability, potential bias, and attribution of results to the Intervention Policy.

Limitation #1: No validated logic model for the Intervention Policy

As indicated previously, there was no logic model developed for the Intervention Policy at the time that it was adopted that outlined the link between the activities, outputs and outcomes.

Mitigation:

EPMRB developed a draft framework logic model based on components of the policy, pre-consultations with key INAC informants, and INAC's Program Activity Architecture. The draft logic model was used to detail the evaluation issues, to guide the data collected, and to assess the success and cost-effectiveness of the Intervention Policy. This logic model has, however, not been finalized.

Impact on Evaluation:

The emphasis in the evaluation and the interpretation of the results could change if there are changes in the logic model, particularly in terms of the long-term outcomes.

Limitation #2: Availability and reliability of data and data analysis

- Some bands had incomplete information due to the fact that data came from a multitude of sources. This affected the analysis because the total population differed from one analysis to another. Data on the CWB and financial information are the variables with the most missing data. Between 25 and 28 percent of the data was missing in the case of CWB because Statistics Canada did not collect census data in all First Nation communities. Between five and seven percent of the data in the case of financial information was missing because bands were under a self-governance agreement (34 bands), bands did not receive funding for essential programs and services directly from INAC but rather through their tribal councils (30 bands), bands did not have a funding arrangement with INAC (three bands), bands had split into more than one band, or the band received less than $30K.

- INAC changed its financial information system from TPMs to FNITP in 2006/07 and the configuration of FNITP differs from TPMs. Financial information, therefore, had to be extracted manually for each band and re-entered onto the database for analysis. Only data for fiscal year (FY) 2004/05 to 2008/09 was therefore extracted.

- A comprehensive picture of the total duration of intervention could not be compiled because of the time required to validate data and changes in the financial system. The analysis of duration was therefore limited to the timeframe from 1999/2000 to 2009/2010.

- There was no statistical competency to derive a composite intervention index that incorporated both the level of intervention and the duration of intervention. Therefore, the correlations between this composite index and other variables were not analyzed. Given the limitations of the underlying data, however, it is questionable whether this composite index would have contributed any additional insights.

- No quantitative data was available on the costs of intervention for INAC. No comprehensive and comparable data was available on the costs of intervention for recipients, except for the cost of TPMs.

- No comprehensive and comparable performance data is available on the quality of services provided by recipients, either under intervention or not under intervention.

- Health Canada does not collect data on recipient-managed intervention, and does not compile data at the national level on co-managed intervention.

Mitigation:

- Intervention data was validated with INAC's regional offices to increase its reliability; the coding of band numbers in different databases was cleaned based on the First Nation Profile Website; and some bands were removed to address the limitations in the financial data noted above. Where data was determined to be incomplete or unreliable – e.g. dependence on INAC funding – it was not used in the data analysis.

- The scope of the data analysis was reduced in some instances – i.e. financial information from 2004/05 to 2008/09 rather than 1999/2000 to 2009/2010; duration over an 11-year timeframe rather than the entire history of intervention; limited comparison with Health Canada intervention data.

- Different statistical tools were used to conduct the analysis depending on the nature of the underlying data – i.e. averages, frequencies, correlations, Anova and chi squares.

- Caution was exercised in the interpretation of the results where a significant number of cases were missing – i.e. for the CWB, or for the cumulative deficit.

- Qualitative information was used from the interviews to supplement the quantitative data that was missing – i.e. on the costs of intervention and the impact on the quality of services.

Impact on Evaluation:

While the evaluation includes an accurate profile of intervention and a statistical analysis of some of the contextual factors that may affect the level or duration of intervention, other statistical analyses of underlying causes were not possible and have not been included. The analysis of cost-effectiveness is also limited by the lack of comprehensive quantitative information on costs.

Limitation #3: Potential Bias in Case Studies

In terms of the key informant interviews and case studies, about 60 percent of the recipients were interviewed despite repeated follow up by telephone and email with all of the contact persons. In terms of success cases – First Nations that have never been under any form of intervention – and in terms of co-managers and third party managers, it has been the least successful (33 percent of the sample). Interviews with First Nations that have been under co-management and/or third party management for more than five years were the most successful (77 percent of the sample). Three Indian-administered organizations were also interviewed.

In some cases, interviews were scheduled but the interviewees were no longer available at the designated time. There was not sufficient time to select alternate cases to replace those cases where recipient interviews could not be conducted. Funding Services Officers were, however, interviewed for all of the cases. There is, therefore, a potential for bias in the case studies towards INAC's perspective rather than recipients' perspective.

Mitigation:

The recipient interviews have been supplemented by the perspectives of national Aboriginal organizations, by the document review, and by the literature review.

Impact on Evaluation:

The evaluation may not reflect the full range of perspectives among recipients and among co-managers and third party managers and may be biased towards INAC's perspective. Where recipient views are referenced, they may emphasize views about co-management and third party management more than views about recipient-managed intervention.

Limitation #4: Availability of historical informationAnother limitation in the case studies was the availability of historical information. Since many of the cases covered a decade or more of intervention, there was very little documentation from the earlier stages of implementation. In addition, remedial management plans for the cases were often not up to date (refer to Section 7, Evaluation Findings - Delivery). In a few cases, the recipient contact persons and the Funding Service Officer were relatively new and did not have a historical perspective.

Mitigation:

The case studies were written up on the basis of the information available or received. For a few of the interviews, previous chiefs or councillors or funding service officers who would have a historical perspective were tentatively identified.

Impact on Evaluation:

The case studies vary in terms of the depth of the historical analysis.

Limitation #5: Availability of documentation

The only constraint in terms of the document review was that the NWT did not provide any remedial management plans for the RMP analysis.

Mitigation:

An interview was conducted with regional officials in the NWT to obtain information on the implementation of the intervention policy in that region.

Impact on Evaluation:

The NWT region is unique within INAC because only three of the 26 First Nation bands in the territory have a land base; essential services are funded by INAC through the territorial government and not directly to bands; and the regional office does not report to Regional Operations Sector at INAC HQ but rather the Northern Affairs Sector. The lack of RMPs for the NWT is therefore not seen as a major constraint in terms of the evaluation findings on RMPs.

Limitation #5: Analysis of impact and attribution to the Intervention Policy

As indicated in the findings on Success (Section 4), any positive changes in the incidence, level and duration of intervention and the cumulative deficit of First Nations cannot necessarily be attributed to the Intervention Policy. Evidence from interviews, case studies and the data analysis would indicate that other factors, such as access to own source revenue, economic risks in particular economic sectors, the degree of geographic isolation, very small size, lack of a land base, or the unwillingness of creditors to lend money can also have an impact on the incidence, level or duration of intervention. Variations across the regions in terms of these other factors also mean that it is not possible to attribute regional variations in results to differences in the ways that the regional offices are implementing the Intervention Policy.

Mitigation:

Limitations on attribution were noted in the findings and analysis, as well as the underlying causes and contextual factors that could affect the success of the policy.

Impact on Evaluation:

The evaluation is not able to attribute success in the achievement of long-term outcomes or variations across regions to the implementation of the Intervention Policy. This is due to a number of other factors or intervening variables. The evaluation does, however, include suggestions for alternatives to the Intervention Policy that could address these other underlying factors.

2.5 Evaluation Governance, Management and Quality Assurance

EPMRB of INAC's Audit and Evaluation Sector directed and managed the evaluation in line with its Engagement Policy and Quality Assurance Strategy. Unless otherwise noted, the Institute On Governance carried out the evaluative work.

EPMRB set up an external Advisory Committee to provide it with ongoing advice on the evaluation. The Advisory Committee included representatives from the Department of Finance and the Treasury Board Secretariat and one First Nation organization, and members were invited to participate in the two workshops of the subject expert panel. EPMRB also set up an internal working group that included representatives of Transfer Payment and Financial Policy Directorate (part of the Chief Financial Office), Regional Operations Sector, and INAC regional offices.

The evaluation methodology report and the draft evaluation report were peer reviewed for quality assurance and compliance with relevant evaluation policies of Treasury Board, INAC and EPMRB.

2.6 Presentation of Findings and Analysis

The next section provides a summary of the findings and conclusions in relation to the evaluation questions, drawing from the different lines of evidence. For the qualitative data, certain terms were used to indicate the proportion of respondents, regions, or case studies to which the finding refers; or other terms to indicate the frequency. These terms are roughly equivalent to the following percentages:

| Proportional Term | Frequency Term | Percentage Range |

|---|---|---|

| All | Always | 100% |

| Almost all | Almost always | 80-99% |

| Many | Often, usually | 50-79% |

| Some | Sometimes | 20-49% |

| Few | Seldom | 10-19% |

| Almost none | Almost never | 1-9% |

| None | Never | 0% |

Findings may not apply to certain respondents, regions, or case studies because no response was provided or no response could be inferred from other comments; or because a different response was provided. Where possible, alternative views, as well as the views of the majority, are presented.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

3.1. Continuing needs and priorities

Is the Intervention Policy responding to actual needs?

According to almost all INAC officials, the Intervention Policy meets the needs of First Nation communities and other recipients by assisting them to manage within the resources available, to ensure the ongoing delivery of essential services, and to be accountable to INAC. Many of the recipients agreed that the Intervention Policy was necessary, especially at the recipient-managed and co-managed levels. Almost all of the recipients under third party management, however, did not agree that the Intervention Policy met their needs.

An analysis of the triggers for the First Nations under some form of intervention as of February 4, 2010, indicates that the cumulative operating deficit is overwhelmingly cited as a reason for intervention (i.e. in 82.12 percent of all First Nations). This is particularly true for co-managed intervention (88 percent of the First Nations) and recipient-managed intervention (85 percent of the First Nations). For third party management, the reasons are more varied, but the cumulative operating deficit as well as the risk of insolvency are still important considerations (72.22 percent of the First Nations).

The case studies indicate that operating deficits and debt can affect the delivery of essential services to First Nations by:

- Increasing cash flow problems leading to delayed social assistance payments, delayed salary or benefit payments, delayed payments to provincial school for students, and to other suppliers, halts on construction projects, etc.;

- Increasing the cost of doing business and delivering services by increasing the cost of capital;

- Reducing the flexibility to enhance services, to maintain capital infrastructure, to build capacity, or to promote economic development;

- Restricting access to new funds from INAC or creditors for improved housing, infrastructure, economic development, etc.; and

- In extreme cases, risking the seizure of all program funds by creditors, or increase creditor control.

The next most prevalent reason for intervention is a denial or adverse audit opinion (10.6 percent of all First Nations). A denial, adverse or qualified audit opinion may be an indication that financial management and accounting procedures are deficient or that the First Nation has refused to provide information for a consolidated audit. An accurate picture of the financial health of the recipient is therefore not available. The recipient then runs the risk of increasing deficits beyond their carrying capacity, of not being able to recover certain expenditures because they have not been properly accounted for, or of losing the confidence of funders and creditors. Unqualified audits, on the other hand, provide accurate reporting to the council or other governing body, the members, funders, creditors and other stakeholders.

In terms of third party management, some of the other reasons recorded on FNITP for intervention are:

- A serious breach of the terms and conditions of the funding arrangement (27.78 percent of First Nations under third party management);

- The health, safety or welfare of First Nation members is being compromised (22.22 percent of First Nations under TPM); or

- Other reasons (44.44 percent of First Nations under TPM).

Our interviews with INAC regional officials and the case studies indicate that serious breaches or other reasons could include the refusal to sign a funding agreement or to provide a consolidated audit. A less common reason is a serious election dispute and no legitimate leadership in place. Even if no funding agreement can be concluded, essential services still need to be delivered to First Nation members.

Many of the recipients and other key informants noted that First Nations also needed access to other sources of funding, increased funding from INAC, or increased flexibility in order to address their needs and build capacity.

3.2 Consistency with federal government and INAC priorities and policies

To what extent does the Intervention Policy align with a) federal government's priorities; and b) with the departmental strategic outcomes?

Over the past 30 years, program delivery has been transformed from direct delivery by INAC to delivery by First Nations through transfer payments. The Intervention Policy is consistent with federal government priorities and departmental strategic outcomes by supporting adequate oversight and stewardship of these resources; ensuring that First Nations receive and provide essential services; and ensuring that health and safety are protected; while also helping to build the administrative capacity of First Nation governments and organizations.

The Intervention Policy is most closely aligned with the Governance and Institutions of Government Program Activity of INAC's Program Activity Architecture. This Program Activity seeks to foster "stronger governance and institutions of government through supporting legislative initiatives, programs and policies, and administrative mechanisms that foster stable, legitimate and effective First Nations and Inuit governments that are culturally relevant, provide efficient delivery of services and are accountable to their citizens."[Note 8]

3.3 Duplication or overlap

Does the program duplicate or overlap with other programs, policies, or initiatives delivered by other stakeholders? (including other federal departments)

Research demonstrated that the INAC's Intervention Policy is one of its kinds and there were no duplication with other initiatives delivered by other stakeholders. There is little guidance on intervention in the Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Transfer Payments as the purpose was to provide flexibility to departments. According the Policy, in the event of a default under a funding agreement, the repayment of the grant or contribution may be required,[Note 9] the funding agreement may be terminated, or "other remedies and procedures" (unspecified) may be provided for.[Note 10]

Health Canada has used INAC's Intervention Policy as the basis for the design of its own intervention policy; and participates with INAC in the development of the third party management framework and the pre-qualification of third party managers. INAC and Health Canada HQ officials indicated that they let each other know if TPM is required and INAC advises Health Canada if a Canada-First Nation Funding Arrangement is going to be terminated due to intervention. Health Canada looks to INAC to support the development of general management and administrative capacity within First Nations and tribal councils and focuses on building the capacity of health related entities.

The First Nations Financial Management Board (FNFMB) has also used INAC's Intervention Policy as the basis for its own intervention policy. FNFMB is working closely with INAC on revisions to the policy and exploring how information can be better shared between the two for mutual benefit.

3.4 Federal government role and responsibility

Does the Intervention Policy align with the federal government role and responsibility?

The Intervention Policy is an operational policy that supports the federal government's roles and responsibilities as it helps to maintain the continuity of essential services to First Nations. However, the federal government is not responsible for First Nations' debt,[Note 11] but debt can have an impact on the delivery of essential services.

3.5 Conclusions related to relevance

- There is a continued need to protect funding for programs and services, to support the delivery of essential services, and to ensure accountability for how federal monies are spent. There is also a continued need to build the capacity of recipients to manage and administer funds.

- The Intervention Policy is consistent with federal government and INAC plans and priorities and the federal government's roles and responsibilities.

- INAC's Intervention Policy has been used as the basis for the intervention policies of Health Canada and FNFMB; and INAC, Health Canada and FNFMB are working together to coordinate changes to the policy.

4. Evaluation Findings - Performance (Effectiveness/Success)

4.1 Intervention trends

What are the intervention trends?

Indicators

A review of documentation demonstrated that no performance measurement has been developed for the Intervention Policy. But since the beginning of the implementation of this policy, internal services measured some indicators, such as the number of communities under intervention, their level of intervention, the deficit ratio and the reasons for being under intervention. However, in the recent Report on Plan and Priorities information on the percentage of First Nations communities under financial intervention has been added[Note 12]. This information depends on different factors, such as the consistency of the end-user to input the information in the information system some reliability issued rose during the collection of the data. The information below on the incidence and level of intervention, as well as the duration were collected through regional offices rather than the FNITP system to ensure the reliability of the information. In this case, there may be inconsistencies with the information used by the Transfer Payment Directorate (i.e. departmental performance report) as the process to collect the information differs. Indicators based on a review of the documentation on Intervention Policy since the `90 as well as based on the observations of the evaluators during this process are listed in Appendix K.

Incidence and Level of Intervention

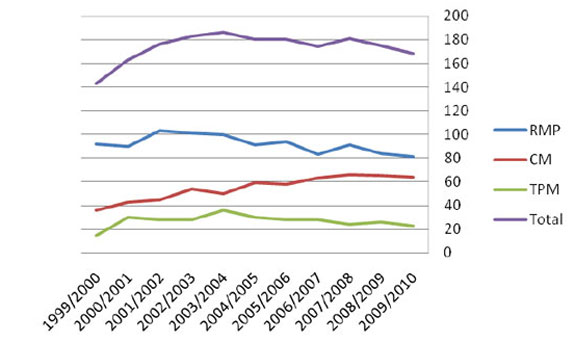

One measure of the success of the Intervention Policy over the long-term is the incidence and level of intervention – i.e. the more successful the policy, the lower the number of recipients under any form of intervention (incidence) and the lower the level of intervention. As Chart 1 below and Table 1 (Appendix I – Data Tables) indicate, the total number of First Nations under some form of intervention actually increased for the last 11 years (1999/2000 to 2009/2010). However, the total number has however declined from its peak in 2003/04 and has been on a downward trend since 2007/08 when the Intervention Policy was introduced. As of March 31, 2010, there were 168 First Nations under some form of intervention, or 29 percent of the total number of First Nations to which the Intervention Policy applies.[Note 13]

Chart 1 - Number of First Nations Under Intervention