Evaluation of On-Reserve Housing

January 2017

Project Number: 1570-7/15108

PDF Version (612 Kb, 60 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Relevance – INAC’s Approach to On-Reserve Housing

- 4. Performance – The State of On-Reserve Housing

- 5. Program Design

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A – Bibliography of Research Reviewed

List of Acronyms

| CMHC |

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation |

|---|---|

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| INAC |

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

Executive Summary

Overview

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB), in compliance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and the Financial Administration Act, conducted an evaluation of the On-Reserve Housing Program. The purpose of the evaluation was to provide a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance of the program, and to inform decision making and future directions.

This evaluation examines the design and impacts of activities directly related to the On-Reserve Housing Program (such as formula-based support for housing, and other proposal-based and capacity development initiatives). It also discusses the implications of related programming such as the Ministerial Loan Guarantees and the Shelter Allowance component of the Income Assistance Program, and initiatives offered by other departments or agencies such as the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Health Canada, and the First Nation Market Housing Fund.

The Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on September 25, 2015. Preliminary planning work was undertaken between November 2015 and March 2016, with primary field research conducted between April and October 2016. The work was led by an evaluation team from EPMRB at INAC, supported by the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation and the consulting firm Ference and Company.

Scope and Methodology

While the scope of the evaluation extends from the previous evaluation completed in 2011 to November 2016, broader data and historical research are included in the analysis to provide a thorough understanding of housing on-reserve, and the relative impact of related government initiatives since the introduction of INAC's current approach to On-Reserve Housing in 1996.

The evaluation triangulated evidence from: over one hundred literature sources; the analyses of policy, legislative and legal frameworks related to lands and housing on-reserve; an analysis of all raw data submitted by First Nations receiving annual housing allocations (2005-06 to 2014-15); interviews with 72 key informants associated with on-reserve housing program administration (including 49 First Nation representatives and experts); and site visits to 26 First Nation communities. The latter included reviews of current policies, practices and issues, and occasionally was done to coincide with home inspections, as First Nation housing managers felt the information gathered would be illustrative of their challenges or successes.

Key Findings

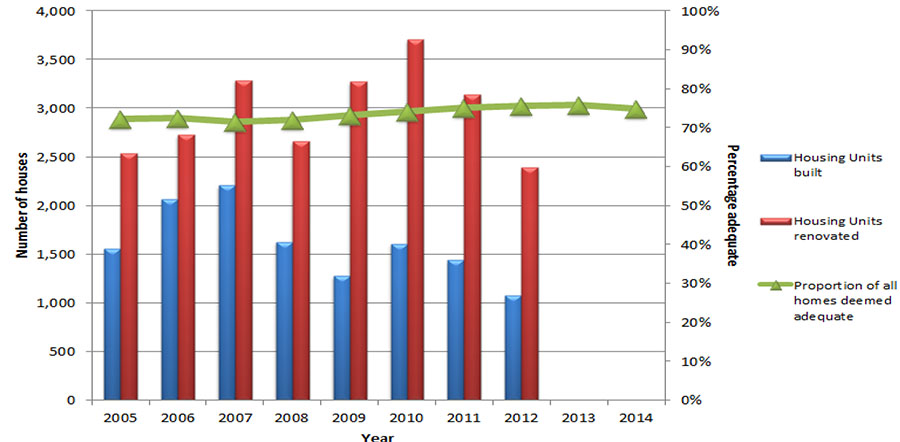

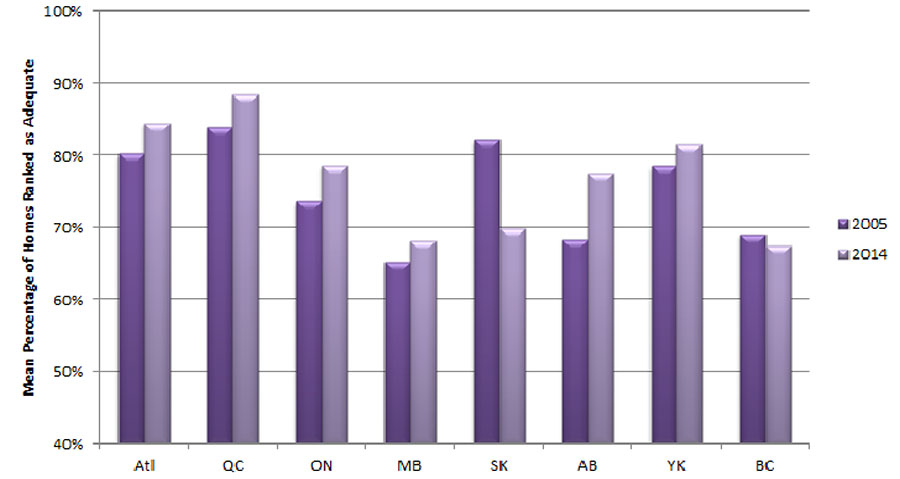

While nationally about three-quarters of homes on-reserve are deemed by First Nation housing managers to be "adequate," issues of overcrowding, poor states of repair, inadequate infrastructure, as well as lack of affordability, are widespread. Long-term improvements have been limited. Housing on-reserve is complex in its processes and outcomes. It is intended to be the responsibility of First Nations, emphasising First Nation control, expertise, shared responsibilities, and increased access to private sector financing.

Evidence gathered throughout the evaluation suggests that INAC's approach to on-reserve housing could be modified in order to achieve better results. While short-term successes stemming from large influxes of proposal-based funding were observed, INAC's overall approach to on-reserve housing has not resulted in long-term broad improvements, and was seen by evaluation participants as short-sighted and non-strategic.

INAC's goal is to work with First Nation governments to support affordable, adequate and sustainable housing. Its approach to achieve this support has primarily been via funding determined by a formula that considers population, degree of isolation, and other variables as part of its capital allocation; to provide contributions via proposal-based projects; and to support various initiatives to work around land and property acquisition limitations stemming from the Indian Act. This support is provided as a matter of social policy (there is no legislative authority or requirement to do so). While its role may be technically appropriate, and while there have been many highly productive initiatives supported by INAC, the evidence reviewed suggests its approach needs to be more proactive and strategic in empowering First Nations to address their underlying capacity and resource challenges for broader and longer term improvements.

First Nation communities have demonstrated enormous innovation and resilience, in many cases partnering with other communities, organisations and government to strengthen housing stock and improve well-being. Ultimately, however, without adequate support for capacity building and First Nation-driven initiatives, broad improvements remain elusive.

The evidence in this evaluation suggests that First Nations need to be extensively and proactively engaged in redefining the relationship with INAC respecting its support to on-reserve housing, and that the Department needs a comprehensive and holistic approach to on-reserve housing that is long-term in its focus. It should meet First Nations' needs and be capacity-driven, and where appropriate and desired, should include strong support for innovation and efficiencies that better empower communities to manage their housing stock, including supporting the development or strengthening of conglomerate organisations to support First Nations.

Recommendations

It is therefore recommended that INAC:

- Engage First Nations to develop a clear departmental mandate to strengthen long-term capacity and governance with respect to housing. This engagement should be proactive, inclusive and meaningful, and with a view to better align departmental activities with the On-Reserve Housing Policy's stated principles of First Nation control, expertise, shared responsibilities, and increased access to private sector financing.

- Provide INAC program officials with a strong and clear mandate and funding flexibility to proactively support individual First Nations and their designated professional organisations, where applicable, to better address their self-determined needs.

- In collaboration with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, develop a simplified approach to funding. This approach should be supportive of long-term planning and reduce bureaucratic burden on First Nations.

- Strengthen the capacity development of existing or new service organisations that provide technical support, capacity development or management services to interested First Nations. These organizations may be national, regional or sub-regional in nature. This work should be done in collaboration with First Nations.

- Engage First Nations in articulating reporting requirements that would better serve their needs, while also better serving public reporting needs. This engagement should be proactive, inclusive and meaningful.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of On-Reserve Housing

Project #: 1570-7/15108

1. Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan was developed to address recommendations resulting from the Evaluation of On-Reserve Housing, which was conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch.

Research shows that poor housing conditions can create social and economic exclusion, and have been linked to health and social problems, including the spread various infections and diseases, high dependency rates to Income Assistance, drinking and substance abuse, family violence, and suicide. Access to safe and affordable housing is essential for improving economic and social outcomes and supporting healthy, sustainable First Nation communities. There is a clear need to address the existing backlog of on-reserve housing needs. Support for on-reserve housing stimulates First Nation economies by supporting job creation, training, and business development.

Regional Operations recognizes the findings highlighted by the evaluation regarding the relevance and performance of on-reserve housing. Specifically:

- INAC supports housing through formula-based funding and occasional investments in pilot projects and targeted funding;

- There is a need for continued investments in on-reserve housing;

- Some First Nations develop and manage their housing stock in impressive and innovative ways; and,

- There is an opportunity to better support the capacity development and self-determination of First Nations housing on reserve.

The evaluation provided five recommendations to improve the design and delivery of housing programs. All recommendations are accepted by the program and the attached Action Plan identifies specific activities by which to address these.

The first, third, and fourth recommendations speak to engaging with First Nations to principles of the 1996 On-Reserve Housing Policy (First Nations control, community capacity, shared responsibility, and access to financing), developing indicators of housing needs and results, and supporting First Nation-led institutions. The second and fifth recommendations involve working internally and with CMHC to ensure processes more effectively support First Nations.

The timing of this evaluation and the recommendations will support the Department in activities leading to new approaches to on-reserve housing. As directed by the mandate letter for Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs, the Department, with support from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, is engaging First Nations and partners to seek input on the reform of the on-reserve housing programs. An effective long-term approach will be developed to support the construction and maintenance of on-reserve housing that meets the needs of First Nations. The recommendations provided in this evaluation will be considered as part of this reform.

As a first step, through Budget 2016, INAC is investing approximately $400 million over two years beginning in 2016-2017 to support immediate housing needs, capacity development and innovative projects. Working with CMHC, INAC has initiated a collaborative engagement approach with First Nations to guide the strategic direction to reform on-reserve housing. The engagement will respect and strengthen the renewed nation-to-nation relationship between the Government of Canada and Indigenous Peoples based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership.

Actions to address the recommendations will continue over the next 12 months.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Engage First Nations to develop a clear departmental mandate to strengthen long-term capacity and governance with respect to housing. This engagement should be proactive, inclusive and meaningful, and with a view to better align departmental activities with the On-Reserve Housing Policy's stated principles of First Nation control, expertise, shared responsibilities, and increased access to private sector financing. | We do concur. |

Director General, Community Infrastructure Branch, Regional Operations Director General, Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch |

Start Date: |

Regional Operation Sector will support First Nations to address their housing needs and aspirations and to meaningfully engage with them regarding on-reserve housing support:

|

Completion: Completed |

||

| 2. Provide INAC program officials with a strong and clear mandate and funding flexibility to proactively support individual First Nations and their designated professional organisations, where applicable, to better address their self-determined needs. | We do concur. |

Director General, Community Infrastructure Branch, Regional Operations Director General, Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch |

Start Date: |

The provision and management of housing on reserve is the responsibility of First Nations. The Government of Canada allocates an annual investment to support First Nations through INAC. In most cases, First Nation communities receive an annual capital allocation for housing from the Department. Annual allocations have been designed with the flexibility that First Nations may use the funding at their discretion for a range of eligible housing needs, including: construction, renovation, maintenance, insurance, capacity building, debt servicing, and the planning and management of their housing portfolio. Through engagements, Community Infrastructure Branch heard the expansion and/or development of national, regional or sub-regional First Nation service organizations must be First Nation led, with support for First Nation leadership and members. The scope and mandate of such potential organizations would be determined by First Nations. To respond to this recommendation, the following steps will be undertaken:

|

Completion: Completed |

||

| 3. In collaboration with the CMHC, develop a simplified approach to funding. This approach should be supportive of long-term planning and reduce bureaucratic burden on First Nations. | We do concur. |

Director General, Community Infrastructure Branch |

Start Date: |

Community Infrastructure Branch is engaging First Nations and partners to develop a new approach to on-reserve housing. The role of INAC and CMHC will be discussed through this engagement. In addition, INAC and CMHC has established a Tiger Team to examine the new approach to on-reserve housing and long-term planning. The Tiger Team, composed of INAC and CMHC representatives, will oversee activities related to on-reserve housing reform. It will be co-chaired by CIB and CMHC and directed by an ADM level Steering Committee. The Tiger Team will focus on reviewing the current roles and responsibilities, develop a work plan to manage future engagement and transitional agenda leading to the implementation of reform. |

Completion: Underway Revised to Q4 2017-2018 |

||

| 4. Strengthen the capacity development of existing or new service organisations that provide technical support, capacity development or management services to interested First Nations. These organizations may be national, regional or sub-regional in nature. This work should be done in collaboration with First Nations. | We do concur. |

Director General, Community Infrastructure Branch, Regional Operations Director General, Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch |

Start Date: |

Community Infrastructure Branch is engaging First Nations and partners to develop a new approach to on-reserve housing. Through engagements to date, the Department heard the expansion and/or development of national, regional or sub-regional First Nation service organizations must be First Nation led, with support for First Nation leadership and members. The scope and mandate of such potential organizations would be determined by First Nations. The Sector has taken the following steps to respond to this recommendation:

|

Completion: Completed |

||

| 5. Engage First Nations in articulating reporting requirements that would better serve their needs, while also better serving public reporting needs. This engagement should be proactive, inclusive and meaningful. | We do concur. |

Director General, Community Infrastructure Branch, Regional Operations Director General, Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch |

Start Date: |

Community Infrastructure Branch and Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch, in partnership with regional offices, has been engaging with First Nations on a number of issues including how best to support articulate reporting requirements. To address this recommendation, the following actions have been taken:

|

Completion: Completed |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed by:

Lynda Clairmont

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations Sector

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This document constitutes the final report for the evaluation of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program's On-Reserve Housing sub-program, conducted in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results. The report presents findings relating to the challenges, successes and innovative approaches to housing issues in communities on-reserve, and provides insights regarding the relevance and performance of related INAC programming. The observations consider the impacts of INAC's Ministerial Loan Guarantees and the report comments on the roles of some other peripheral initiatives such as the First Nations Market Housing Fund and the Shelter Allowance component of the Income Assistance program.

Preliminary work was conducted between November 2015 and March 2016. Primary field research was conducted between April and October 2016 by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) evaluators at INAC. Support was provided by the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation and the consulting firm Ference and Company.

1.2 How to Read this Report

Given the complexity of housing on-reserve, this report is structured in a way that first outlines the historical and legislative context with respect to lands, and details INAC's intended role. From describing the intended role, the report then describes how INAC has managed the housing sub-program, and generally how housing is managed on-reserve in practice. The report then delves into the current state of housing using data reported by First Nations to INAC as well as the Canadian Census. Based on the evidence presented, the report concludes with observations on how incorporating some key initiatives into the general design of the program might facilitate better outcomes.

Recommendations are found throughout the body of the report and then summarised in the concluding section. Importantly, this evaluation considered that engagements and other initiatives to reform INAC's approach to on-reserve housing were simultaneously underway. Therefore, highly prescriptive recommendations on all potential issues discussed are avoided so as not to presume the outcomes of those initiatives. The intention was that this evaluation would serve as one of several pieces informing the way forward.

There have been numerous studies and reports on the condition of homes on-reserve, as well as the multitudes of challenges facing on-reserve communities. The aim of this report is not to restate the many observations of previous studies or reports, including those of the recent Senate Committee; rather, it is to evaluate INAC's approach against its stated objectives and lay out recommendations to support ongoing program improvement and results achievement.

1.3 Program Context

Housing on-reserve works differently than off-reserve, particularly in relation to property ownership. Off-reserve land holdings and housing are primarily based on individual ownership. Individuals purchase pieces of land and the house(s) on that land. Individual ownership does not exist this way on-reserve. Under the Indian Act, reserve lands are held by the Crown and are set aside for the use and benefit of a band.

Housing on reserves varies among First Nations in policies, rules, customs and capacity, and may be divided into two broad categories: 'band-owned' housing, consisting of an estimated two-thirds to three-quarters of all housing on reserves and 'individually-owned' housing. Band-owned or individually-owned housing allocations may be applied in nearly any combination to the broad range of land holdings on reserves, whether individually-held (e.g., individual with a Certificate of Possession) or communal (First Nation social housing on general band lands). Ultimately, it is the First Nation that has the right to decide how they manage housing on-reserve.

Many First Nation families rent homes on reserves from their First Nation or from another First Nation member. The interests or rights of individuals renting on-reserve are not as clear as those off-reserve, nor are there inherent regulatory powers of band councils for rental of housing that would be implied by provincial tenancy statutes (unless a band chooses to adopt those statutes).

Individually-held housing on-reserve lands usually means an individual band member has a right to occupy the home. The ability to modify the existing home or build a new home varies between communities. The band member may also have a right to occupy the land on which the house is located.

Most First Nation communities (except communities in British Columbia, and 20 in Ontario) receive an annual minor capital allocation from INAC for general infrastructure and on-reserve housing, and can use these funds for a range of housing needs, including: construction; renovation; maintenance; insurance; capacity building; debt servicing; and the planning and management of their housing portfolio.Footnote 1 The communities in British Columbia and Ontario who do not receive the annual minor capital allocation are supported by the Housing Subsidy Program.

1.4 Program Profile

1.4.1 Background and Description

INAC supports First Nations on-reserve housing through its On-Reserve Housing Support Program, Ministerial Loan Guarantees and the Shelter Allowance component of the Income Assistance program. In the 1960s, INAC first introduced a housing program to assist in the construction and renovation of houses on reserves. The program provided subsidies for new residential construction and the renovation and rehabilitation of existing houses.

In 1996, what has been referred to as INAC's 'On-Reserve Housing Policy' (see Section 3.1.2)Footnote 2 was introduced in order to provide greater flexibility and more control to First Nations over their housing policies or programs. The 'policy' is based on four elements:

- First Nations control (community-based housing programs);

- First Nation expertise (capacity development);

- hared responsibility (shelter charges and ownership options); and

- Better access to private capital (debt financing).

First Nations could choose whether or not to opt into this approach. If they opted in, they were given a minor capital allocation, with more flexible Terms and Conditions respecting the use of funds in support of the implementation of their community-based housing plans, which could include maintenance and insurance, debt charges, training, management and/or supports to establish housing authorities. The base budget allocated to housing in 1996 was $138 million per year. During the first five years after the introduction of the policy, an estimated $160 million in additional funds was also provided to opting-in First Nations. These additional funds came from a variety of sources, including Cabinet allocations to the post–Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples Gathering Strength initiatives, the program Integrity and Rust Out initiatives, and later from Canada's Economic Action Plan. Generally, the supplementary funds were to accelerate the production of new housing and major repairs and renovations. As of late 2016, most First Nations in Canada, with the exception of First Nations in British Columbia and about 20 in Ontario, have opted into the approach of an annual allocation under the parameters of the 1996 'Housing Policy', which is not necessarily to the exclusion of other proposal-based projects. The remaining First Nations may receive funding in support of housing through proposal-based initiatives.

Given Crown ownership of First Nation lands and the limitations set out in Section 89(1) of the Indian Act, preventing the seizure of land or property as collateral on-reserve, INAC also provides Ministerial Loan Guarantees for community members who need to obtain a mortgage to purchase an existing house or financing to fund the construction of a new one. Ministerial Loan Guarantees can be used to secure loans for the purpose of construction, acquisition, or renovation of on-reserve housing. There is $1.8 billion dollars in guarantee authority currently issued to support First Nations in accessing loans for home ownership and social housing.

Additionally, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) operates a non-profit housing program intended to assist First Nations in the construction, purchase and rehabilitation, and administration of suitable, adequate and affordable rental housing on-reserve. It also provides: direct lending for eligible social housing projects; insured financing (backed by INAC Ministerial Loan Guarantees); contributions and interest-free loans by way of seed funding (which is available for a variety of eligible expenses for projects); and proposal development fund loans (to assist with the initial costs of proposal development). Health Canada also supports community-based health promotion and disease prevention programs, inspection services and mold remediation.

In 2008, the Government of Canada provided $300 million for the establishment of the First Nations Market Housing Fund, with an up-front investment in trust to help First Nation households on-reserve or settlement lands gain easier access to private lending for market-based housing and increase the capacity of First Nations seeking to expand or develop market-based housing. CMHC acts as the Funder and Manager of the Fund. A Board of Trustees is responsible for overseeing the Fund's governance and practices, and guiding its direction to achieve its objectives. There are nine Trustees; six are appointed from the public and private sectors by the Minister responsible for CMHC and three are appointed from First Nation communities by the Minister of INAC.

The First Nations Market Housing Fund is intended to facilitate the ability of individuals to obtain housing loans on a standard market basis from financial institutions, and to provide capacity development, including the provision of training, advice and coaching, focusing on developing market-based housing capacity for qualified First Nations and members of these communities. The key difference between the First Nations Market Housing Fund and the Ministerial Loan Guarantees is that Fund is intended to place greater emphasis on the individual borrower, more akin to off-reserve. The Ministerial Loan Guarantees considers the position of the band administration to carry risk, irrespective of the individual, and is more often used in the context of social housing.

1.4.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

Under the 2015-16 Program Alignment Architecture, the Housing sub-program (3.4.3) supports the provision of funding to First Nations to plan and manage their housing needs, including the design, construction and acquisition of new housing units as well as renovation of existing band-owned housing units. The goal of this sub-program is to work with First Nations to increase the supply of safe and affordable housing to achieve better housing outcomes for their residents.

The expected result for the program as articulated by INAC in its annual Report on Plans and Priorities has been revised over time. In 2011-12, the outcome was considered for infrastructure generally, and was that "Infrastructure base in First Nation communities that protects the health and safety of community members and enables engagement in the economy." Between 2012-13 and 2015-16, the expected result was that housing infrastructure meets the needs of First Nation communities. In 2016-17, the expected result was revised such that 'First Nations housing infrastructure needs are supported'. INAC assesses this using the proportion of housing units reported by First Nations to be "adequate."Footnote 3 This proportion is determined by taking the total number of houses, less the number in need of major repair and/or replacement, and dividing by the total number of houses. INAC does not conduct any inspections to verify reported data.

The program Performance Measurement Strategy considers outcomes for all infrastructure programs together. The result for the housing program matches that of the Report on Plans and Priorities for 2012-13 to 2015-16. The immediate outcomes described in the Performance Measurement Strategy do not mention housing explicitly. The outcomes are that:

- Infrastructure assets are constructed or acquired in First Nation communities;

- INAC has the information it needs to make strategic decisions and First Nation communities have the information they need to allocate resources to manage their INAC-funded infrastructure within established health and safety standards; and

- First Nation communities are supported in managing their assets.

1.4.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

Responsibility for the management of INAC's support to on-reserve housing falls within the purview of the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program of the Community Infrastructure Branch of INAC's Regional Operations Sector. INAC regional offices in turn distribute funds to First Nations using a population-based formula. Recipients of funding can be First Nation bands and tribal councils.

At a national level, INAC supports housing through project-based and ongoing capital funding. Of note is that there is no legislative authority nor Treaty obligations to support housing. Rather, available guidelines or policy articulate that housing is the responsibility of First Nations, supported by INAC as a matter of social policy. Under this understanding, First Nations may receive some support from the Government of Canada. The 'policy' approach is articulated through the Department's guidelines on submitting proposals for minor capital allocations, which require that on-going multi-year housing plans be submitted to INAC regional offices. Given this regional approach, housing on-reserve is managed via a multitude of variable approaches at the discretion of bands or in some instances, tribal councils. These approaches may or may not include housing authorities or band-level policies, or budget allocations from revenue the band generates itself. The beneficiaries of the minor capital allocation include: bands/settlements (land, reserves, trusts); regional, district councils and chiefs' councils; and tribal councils.

1.4.4 Program Resources ($) (Actuals and Estimates)

Detailed actual expenditures and main estimates are detailed in the table below. Over the five fiscal years between 2011-12 and 2015-16, the budget for On-Reserve Housing totaled $716,215,624 and the total spent was $658,383,282 – about $58 million less than the amount budgeted. The bulk of this difference was in contributions.

| Authority Description | Description | 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/1 | 2015/16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution | ALTERNATIVE FUNDING ARRANGEMENT BLOCK/CORE FUNDING - HOUSING | 28,730,946 | 26,564,407 | 27,913,081 | 29,501,075 | 28,973,525 |

| COMMUNITY-BASED ON-RESERVE HOUSING PROGRAMS | 95,000 | 146,125 | 3,589,899 | 3,821,911 | ||

| GATHERING STRENGTH - HOUSING | 6,000 | |||||

| HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 55,175 | |||||

| ON-RESERVE HOUSING, CONSTRUCTION & RENOVATION | 98,792,882 | 88,692,686 | 110,221,273 | 92,393,543 | 96,303,216 | |

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 2,777,759 | 2,679,803 | 3,089,413 | 1,633,482 | 2,676,462 | |

| Contribution Total | 130,402,587 | 117,936,896 | 141,369,892 | 127,173,174 | 131,775,114 | |

| Employee Benefit Plan | HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 23,062 | 33,252 | 139,239 | 71,240 | 70,743 |

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 177,468 | 25,899 | 71,792 | 101,594 | 199,315 | |

| Employee Benefit Plan Total | 200,530 | 59,152 | 211,031 | 172,834 | 270,058 | |

| Operations and Maintenance | HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 11,304 | 6,421 | 5,666 | 329 | |

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 351,411 | 578,684 | 153,545 | 94,818 | 162,984 | |

| Operations and Maintenance Total | 362,714 | 585,105 | 159,210 | 95,147 | 162,984 | |

| Salary | HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 148,577 | 205,109 | 864,357 | 463,988 | 465,006 |

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 1,143,337 | 159,751 | 445,663 | 691,921 | 1,310,135 | |

| Salary Total | 1,291,913 | 364,860 | 1,310,021 | 1,155,909 | 1,775,141 | |

| Statutory Total | ON-RESERVE HOUSING, CONSTRUCTION AND RENOVATION | 1,539,525 | 10,445 | -961 | ||

| Actuals Total | 132,257,745 | 120,485,538 | 143,050,154 | 128,607,509 | 133,982,337 |

| Authority Description | Description | 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/1 | 2015/16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution | ALTERNATIVE FUNDING ARRANGEMENT BLOCK/CORE FUNDING - HOUSING | 140,135,900 | 140,135,900 | 140,135,900 | 134,865,402 | 111,044,458 |

| ON-RESERVE HOUSING, CONSTRUCTION AND RENOVATION | 26,552,725 | |||||

| ON-RESERVE O&M HOUSING SUPPORT | 4,084,416 | 4,084,416 | 4,084,416 | 1,255,416 | 1,117,192 | |

| Contribution Total | 144,220,316 | 144,220,316 | 144,220,316 | 136,120,818 | 138,714,375 | |

| Employee Benefits Plan | ALTERNATIVE FUNDING ARRANGEMENTS BLOCK/CORE FUNDING - HOUSING | 133,269 | -31,399 | |||

| HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 26,613 | 25,237 | 114,154 | |||

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 21,909 | 98,061 | ||||

| Employee Benefit Plan Total | 21,909 | 26,613 | 158,506 | 180,816 | ||

| Operations and Maintenance | HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 29,000 | 34,000 | 24,215 | 23,315 | 113,569 |

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 862,201 | 842,101 | 577,280 | 577,280 | 207,728 | |

| Operations and Maintenance Total | 891,201 | 876,101 | 601,495 | 600,595 | 321,297 | |

| Salary | ALTERNATIVE FUNDING ARRANGEMENTS BLOCK/CORE FUNDING - HOUSING | 918,000 | ||||

| HOUSING SERVICE DELIVERY | 152,950 | 152,950 | 648,652 | |||

| ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 121,719 | 546,679 | ||||

| Salary Total | 121,719 | 152,950 | 1,070,950 | 1,195,331 | ||

| Statutory Total | ON-RESERVE OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE HOUSING SUPPORT | 500,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 |

| Main Estimates Total | 145,755,145 | 145,596,417 | 145,501,374 | 138,450,869 | 140,911,819 |

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

While the scope of this evaluation is officially focused on INAC's Housing sub-program via its capital allocation and other project-based funding, it provides an analysis of the extent to which objectives and outcomes are being met, or can be reasonably expected to be met, and considers the entire suite of government programming, approaches and initiatives of First Nation communities, and INAC's current approach to housing on-reserve. It also considers the Shelter Allowance component of the Income Assistance program with respect to its impacts on housing accessibility and affordability.

The evaluation covers the period from 2011 to November 2016. However, to provide a holistic view of housing issues, and to contextualize outcomes over the long-term, data from prior to 2011 has been considered. For example, studies that led to the culmination of INAC's current approach are drawn upon, and data analysis dates back as early as 2001 to provide a more complete picture of outcomes over time. This is important particularly considering INAC programming has not undergone any significant change since 1996.

The Terms of Reference for this evaluation were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on September 25, 2015. Preliminary work was conducted between November 2015 and March 2016, with primary field research conducted between April and October 2016 by an evaluation team from EPMRB at INAC, and with the support of the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation and the consulting firm, Ference and Company.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The Terms of Reference and methodology for this evaluation were guided by the 2009 Policy on Evaluation, before the adoption of the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results, which has since come into effect. Thus, the questions were set up under the themes specified in the former policy. However, this report is structured in line with the current policy. As detailed in the Terms of Reference, the following questions guided the methodology of this evaluation:

Relevance

Continued Need for the Program

1) Is there a need for the Government of Canada to continue to provide support to First Nations for their provision and management of housing?

2) Is there a need for the Government of Canada to continue to secure loans to support the provision of housing services via the Ministerial Loan Guarantees?

3) Is there a need for the Government of Canada to support market-based housing initiatives on-reserve?

Alignment with Government Priorities

4) Are the current activities related to the Housing sub-program and related supports such as the Ministerial Loan Guarantees, and the First Nations Market Housing Fund aligned with departmental strategic objectives and government priorities?

Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

5) The provision and management of housing on-reserve lands is the responsibility of First Nations, with support from the Government of Canada. Is the Government of Canada's role appropriate and clear in this regard? Are the roles of the respective departments (INAC, CMHC and Health Canada) appropriate and clear?

6) Is the current division of responsibilities between Headquarters and regions, and between the Community Infrastructure Branch and other groups (e.g., the Chief Financial Officer Sector) in program delivery clear and effective?

7) Should INAC be the responsible department for the provision of loan security for housing on-reserve?

8) Is the Government of Canada's current role in supporting market-based housing initiatives appropriate and clear?

Performance

Effectiveness (i.e., Success)

9) To what extent is housing infrastructure currently meeting the needs of First Nation communities?

10) To what extent have there been improvements in the construction and acquisition of housing assets to better meet the housing needs of First Nation communities?

11) To what extent do First Nation communities have the capacity to provide and manage housing?

12) To what extent are the Ministerial Loan Guarantees successful in contributing to better housing outcomes?

13) Is the First Nation Market Housing Fund contributing to a viable and sustainable private housing market on-reserve?

14) What are the key challenges with First Nations meeting the housing needs in their communities? To what extent can these challenges be addressed by the Housing Program?

15) Can current programming be reasonably expected to result in housing acquisition and construction that meets the needs of First Nation communities?

Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

16) Is the current approach to housing programming on-reserve and the relative contribution of the Government of Canada sustainable?

17) Is the value for money (considering quality and life cycle) for construction and repair of homes on-reserve comparable to that off-reserve?

18) Is INAC achieving efficiencies in its housing programming?

2.3 Evaluation Methodology

The methodology for the evaluation was developed through the preliminary field work stage, and was informed by previous research, issues important to First Nation participants, and the current state of knowledge on housing issues on-reserve. To support the methodology, the evaluation employed the following data collection methods.

2.3.1 Approach

EPMRB approached this evaluation with a view to engaging multiple First Nation stakeholders and communities as part of the preliminary design, methodology, evidence gathering and analysis. The intent was to consider evaluation participants as more than just informants to improve relationships between INAC and those partners and lead to a more credible evaluation. While evaluation is inherently a neutral exercise, the partnership approach ensures the evaluation treats information gathered in the right way. For example, the purpose of conducting preliminary research prior to the main field work exercise was to ensure partners and stakeholders provided input on the direction of the project's research questions. This preliminary research included interviews and discussions with Indigenous organisations with on-reserve housing portfolios, as well as two visits to First Nations to discuss methodology and research questions. Another example is the provision of preliminary findings to the project's Working Group and Advisory Committee, both of which include delivery partners and stakeholders with unique points of view, for their reaction and feedback prior to the final analysis.

2.3.2 Data Sources

Literature and Document Review:

The literature search was guided by the evaluation research questions, as well as additional queries stemming from the preliminary research, and using academic search engines, as well as INAC's library. One hundred and one articles (excluding articles that summarized the same information) were directly drawn upon to inform the findings in this report. See Annex B for Bibliography. Key themes included historical analysis of land use and legislative issues related to housing on-reserve; the current state of housing on-reserve; social housing management models in Canada and in different countries pertaining to Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples; impacts of housing conditions and relationships with other issues; and measures of housing adequacy.

Review of Legislation, Policies and Approaches relating INAC's Housing Programming:

An external consultant conducted a review of documents and literature that summarized the legislative, legal and evolution of INAC's housing approach, culminating in 1996 to what is now referred to as its Housing Policy. The intent of this research piece was to provide a thorough analysis on the extent to which current programming reflects the intent of original policy documents, and how this officially implicates INAC and First Nations.

Database Analysis:

First Nations submit annual recipient reports for their minor capital allocation.Footnote 4 Data were extracted by band administration and coded into SPSS for trend analysis, analyses of variance and regression analysis. This quantitative analysis was used to assess performance outcomes.

Key informant interviews:

Interviews were first conducted to inform the evaluation methodology and plan, as part of case studies, and at the final fieldwork stage to discuss issues in the context of preliminary findings. EPMRB staff conducted interviews with: 25 INAC staff (i.e., individuals determined to have significant involvement in on-reserve housing) CMHC and Health Canada; board members from the First Nations Market Housing Fund; and 49 First Nation experts (i.e., including housing managers, technical experts and representatives of other Indigenous organisations with on-reserve housing portfolios, and chiefs and councils, which were selected using the case study selection methodology described below.

Case Studies:

Case studies were led by EPMRB staff with the assistance of the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation. Each community constituted a case study, with 26 in total completed. Each study illustrated in detail the approach to housing stock management, the challenges faced, and results achieved. The purpose was to gather information on initiatives and approaches that foster positive outcomes, and conditions that may result in challenges. Case studies included interviews with band staff responsible for the housing portfolio, and in some cases, with Chief and council, residents, and other community workers. They also may have included: a series of home inspections in communities where there was a high proportion of band-owned homes; a tour of communities; and an analysis of official documents regarding housing policies, bi-laws, recent or new projects or proposals, and agreements with other municipalities, companies or layers of government for service contracts dealing with infrastructure or housing.

Communities were selected to ensure a mix of regional variation, population, economic activity, remoteness, and housing conditions. Recent housing construction and renovation activity were also considered. Specifically, evaluators sought to visit communities with high levels of construction, and others with few or none, during the 2011 to 2016 reporting periods.

All regions except Yukon were represented in the case studies, as follows: British Columbia (three), Alberta (four), Saskatchewan (three), Manitoba (six), Ontario (three), Quebec (three) and Atlantic (four).

2.3.3 Triangulation and Analysis

The literature and documents reviewed were tabulated and summarised by research question. Information from case studies and interviews were coded using NVivo qualitative software, by research question and further broken down by theme, and then observation. These pieces were triangulated with raw data from recipient reports, and statistical queries on the raw data were generated from qualitative observations and vice versa. Information from interviewees and case studies was analysed to see where concurrence or divergence of opinion emerged, and in turn, these observations were compared to literature, official policy and legislation documents, and raw data. Where there was congruence or divergence of observations from different lines of evidence, these were noted.

2.3.4 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

The information collected and analysed for this evaluation was for the express purpose of producing findings that could inform concrete recommendations for the improvement of housing conditions and management on-reserve. It is difficult, however, to disentangle housing issues from other historical, social, and economic issues, as well as economic and infrastructure issues inherent to rural communities whether or not on-reserve.

The context of on-reserve housing from the Government of Canada's point of view is that housing is the responsibility of First Nations and the stated outcomes of the Government can be very difficult to measure (i.e., meeting First Nations' infrastructure needs are "met" or "supported" ). Despite the fact that findings are related to all levels of housing management and all involved stakeholders, recommendations in this report are made to INAC; not to First Nations or other departments or stakeholders. Thus, recommendations are limited to what INAC can, as a department, enact and/or influence.

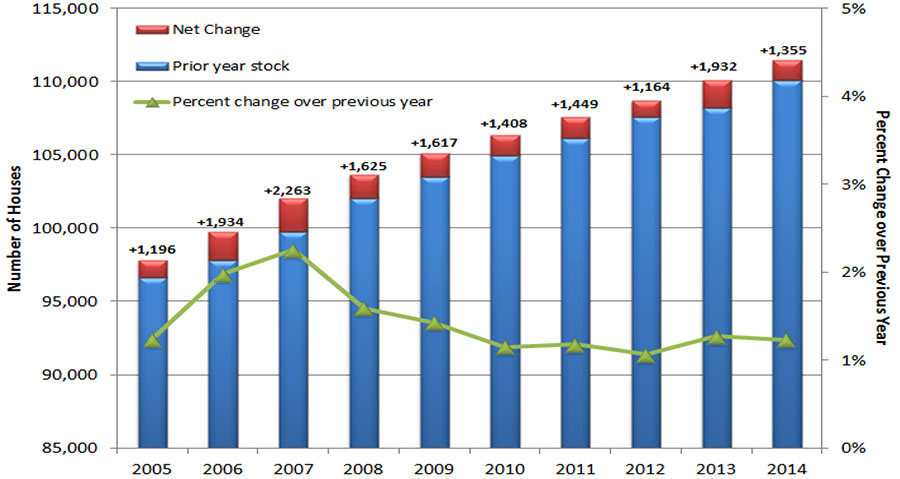

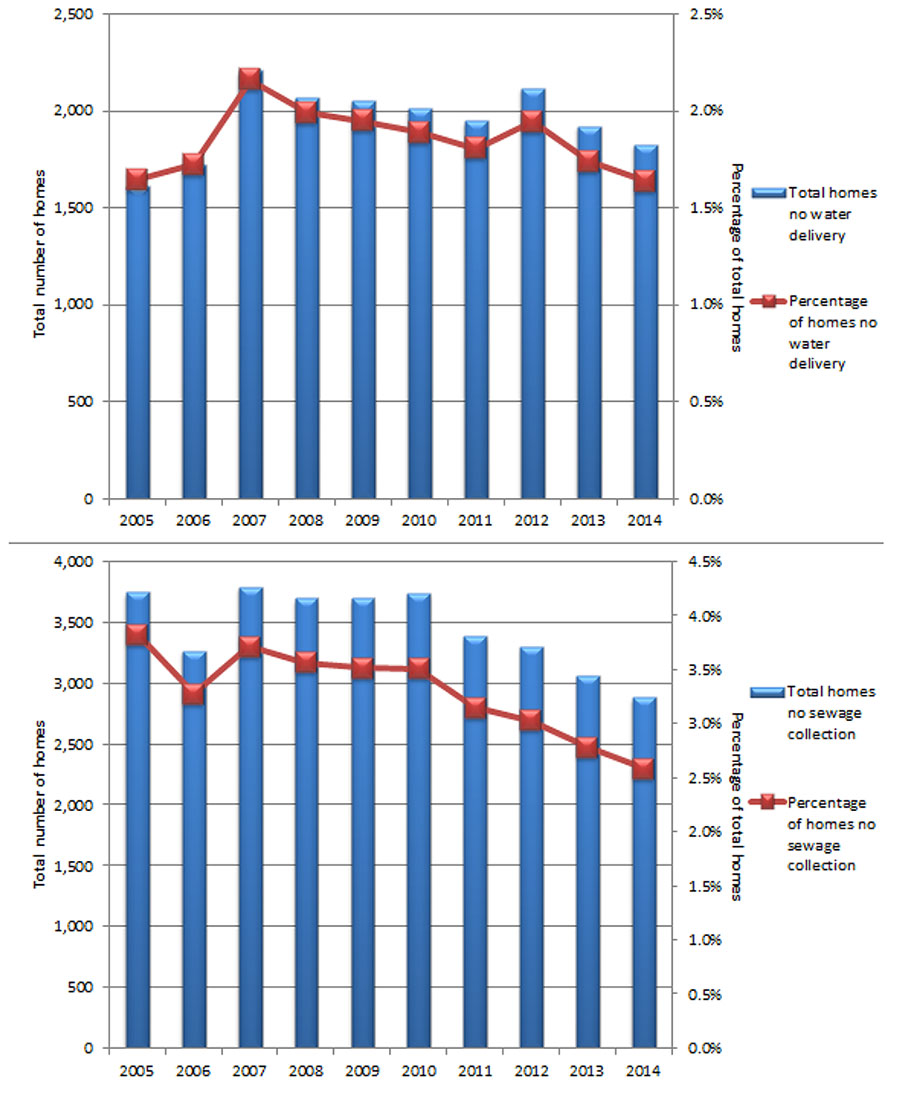

Raw data from reports submitted by First Nation funding recipients include variables such as total housing units, number in need of major repair and replacement; as well as data on water, sewer, roads, etc. These figures are self-reported by band administrators and are not verified for accuracy. Additionally, there are significant issues with definitions (i.e., "major repair") (See Section 5.1). The raw data from recipients was only available up to 2014 at the time of the authoring of this report. Some of the raw data variables end at 2012 because INAC removed them from the data collection instrument in 2013-14. Census variables used in raw data analysis were only available up to the last census in 2011.

This report was conducted with the methodological rigour required for a multi-methodology evaluation project. Given the primarily qualitative nature of the data, the findings are not meant to be generalizable. Rather, the evaluation is intended to seek out key observations and insights that would inform recommendations to INAC on how to approach housing issues with a clear view to making long-term improvements.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

This evaluation was led by EPMRB. The development of the methodology was supported by the firm Ference and Company. The conduct of case studies and analysis was supported by the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation.

A working group was engaged to lend guidance at four key points: the evaluation launch, methodology, preliminary findings, and final report. The working group was comprised of representatives from: INAC's Community Infrastructure Branch; the Income Assistance Directorate at INAC; Health Canada; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation; and the Assembly of First Nations.

An advisory committee was established before primary data collection commenced to help inform the broader objectives and desired impacts of the evaluation. Members included: senior assistant deputy ministers from INAC (Regional Operations Sector and Policy and Strategic Direction); the Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive from INAC; a Senior Assistant Deputy Minister from Health Canada (First Nations and Inuit Health Branch); a Senior Vice President from CMHC (Policy, Research and Public Affairs); a First Nations Chief from Quebec; and a Regional Chief from Manitoba.

The report was circulated to working group members twice in advance of a final draft, and was peer-reviewed by an external consultant.

3. Relevance – INAC’s Approach to On-Reserve Housing

3.1 Understanding the Current Federal Role

INAC'scurrent goal is to work with First Nation governments to support affordable, adequate and sustainable housing. Its approach to achieve this support has been to provide formula-based funding and proposal-based contributions, and to support various initiatives to enable First Nations to overcome land and property limitations and gaps posed by sections of the Indian Act.

INAC's stated outcome with respect to on-reserve housing has changed over time, and as of 2016-17 was outlined as "supporting" First Nation housing infrastructure needs. Previous to this, it has been that housing infrastructure needs are "met." Yet, the formula based funding for housing is simply meant to subsidize some housing-related costs, and in most cases is not nearly sufficient to cover the cost of building a single house, even if the total allotment was dedicated to that purpose. The expectation is that the First Nation will procure their required funds from other sources.

INAC's contributions via its Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program are meant to provide financial assistance to plan, construct and/or acquire and operate and maintain community capital facilities and services (infrastructure, including schools) and housing (residential) consistent with approved policies and standards, which are outlined in the Protocol for INAC-funded Infrastructure.Note de bas de page 5

However, the main point of contention is the degree to which funding, when combined with other resources on-reserve, can reasonably be expected to meet the housing needs of First Nations. It has also been suggested that one important reason that on-reserve housing is of poor quality is the regulatory gap around building code enforcementFootnote 6,Footnote 7 and the capacity of First Nation communities to position themselves to ultimately be responsible for housing writ-large.

3.1.1 The Indian Act and the Use of Reserve Lands

The Constitution Act of 1867 gives Parliament authority over "Indians and lands reserved for the Indians", and the Indian Act sets out the land management responsibilities of the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs for much of the reserve lands in Canada. Land management generally includes activities related to the ownership, use and development of land for personal, community and economic purposes. As identified in the Indian Act, reserve land is "a tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, which has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band". Reserve lands are different from other land in that:

- Legal title to reserve lands is held by the Crown rather than by individuals or organizations;

- First Nations have a recognized interest in reserve land that includes the right to exclusive occupation, inalienability and the communal nature of the interest;

- The land cannot be seized by legal process or be mortgaged or pledged to non-members of a First Nation; and

- The Minister must approve or grant most land transactions under the Indian Act.

Under the Indian Act, individual members of a First Nation may be given allotments (the right to use and occupy a parcel of reserve land). Allotments must be approved by the Band Council and the Minister. Once approved, the individual allotment holder has "lawful possession" of a parcel of land and may be issued a Certificate of Possession as evidence of his or her right. However, the legal title to the land remains with the Crown. An individual may transfer his or her allotment to the band or another band member, may lease the allotment to a third party, and may leave the allotment to another band member in his or her will. All these transfers of individual allotments must be approved by the Minister. If the "lawful possession" holder ceases to be a band member, his or her allotment must be transferred to the band or another band member.

Some First Nations do not choose to allot lands to individual band members under the Indian Act. Instead, they grant the use of lands to particular families or individuals through a custom or traditional holding, sometimes referred to as "informal holdings." Some First Nations use a combination of Indian Act and custom or traditional systems. Previous estimates are that 10 percent of First Nations use formal land management practices under the Indian Act, of which less than three percent of total reserve land covered by Certificates of Possession. Moreover, the vast majority of these Certificates of Possession are in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia.

This complexity regarding the governance of land holdings may be driving a lack of understanding on the part of many First Nations. They do, in fact, have the jurisdiction to adopt by-laws to organize how common lands are developed. In practice, the bulk of a First Nations' lands fall outside their real or perceived authority to govern, or where precise and accurate knowledge of how interests are organized is absent.Footnote 8 This was clearly observed in case studies, where in many cases band managers and housing managers were unaware of their authorities respecting bi-laws or land management in general. In some cases, where they were unaware that they had any authority, they (incorrectly) believed federal legislation was preventing them from exercising their land management rights.

For example, in one First Nation that was selected to participate in case studies, there was no formal system for dividing the community's land. Parcels had been historically allocated informally to families by Indian Agents. The result of this practice is that it is politically sensitive for the housing manager to make any decisions that might affect a family's allocation. As a result, there may be limited ability to add to a family's allotment.

The capacity of First Nations to conduct land use planning was seen by case study and interview participants as critical to their successful management of a housing regime. This is largely dependent upon a clear understanding of land tenure on the part of each band administration. Given the multitude of complex situations respecting each First Nation's current land tenure, it would be essential to approach solutions based on First Nation-specific situations, as opposed to broad-based national or regional solutions.Footnote 9 Presently, these initiatives have been ad hoc on the part of INAC regions and do not stem from any broader departmental direction.

3.1.2 On-Reserve Housing Policy

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the dire housing conditions on-reserve were well-documented and gradually led to a new approach to on-reserve housing. In 1985,Footnote 10 arguments were made that the Government should support First Nations based on determined need, and that the situation on-reserve amounts to a crisisFootnote 11,Footnote 12 with significant social costs.Footnote 13 In 1996, the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People concluded that Aboriginal housing was sub-standard and was threatening the health and well-being of Aboriginal people. Citing the living conditions as intolerable, the report suggested that acute risks to health and safety be treated as an emergency and targeted for immediate action. The report contained eleven recommendations related to housing, including, among others, the need to address adequate housing shortages over a ten-year period, and the need for an injection of additional funds, clarification of treaty rights to housing, increased First Nation control and jurisdiction over housing, the establishment of First Nations institutions, shared responsibility for housing costs, and increased cooperation between First Nations and the Government of Canada.

Based on a series of working group papers in 1989Footnote 14,Footnote 15 and 1990,Footnote 16 INAC developed, in 1996, what is now known as its On-Reserve Housing Policy.Footnote 17 It is intended to give First Nations a key role in how, where and when housing funds are invested. It is based on the principles of: First Nation control, First Nation expertise, shared responsibilities, and increased access to private sector financing. However, key-informant interviewees and First Nation housing managers indicated that in practice these goals have not materialised to the extent anticipated, and INAC's role has been described by interviewees as reactive, with large injections of proposal-based funding at key points in time; most notably in 1996 and 2008 (Canada's Economic Action Plan) but lacking strategic support for capacity development and long-term improvement.

At the outset of the development of this new policy, it was clear that there was an intention to operate on the stated principles, with a view to First Nations self-determination and long-term improvements. Opting into this process would allow allotted funds to cover costs not previously covered (e.g., insurance, debt-servicing, etc.). However, there would be no additional ongoing funding for this. The Guidelines for the Development of First Nations Housing Proposals,Footnote 18 which articulated the process for First Nations wishing to opt into the new policy, allowed First Nations to access one-time funding (over five years, if they wished) for costs of developing multi-year housing management plans and related governance structures for their communities.

The multi-year plans were to have three components: a work plan, a resource plan, and a plan linking housing activities with training, job creation and business development initiatives. The work plan was to define the tasks to be undertaken by year, including: maintaining and insuring existing houses to ensure essential repairs and routine work are completed; protecting the housing and preventing premature deterioration; renovating substandard units; building new houses or expanding existing homes to reduce over-crowding and meeting the need of new families; and ongoing management of the community housing program. Housing plans were to be linked to communities' infrastructure servicing plans such as water, sewer, roads and sub-division development.

The resource plan was intended to provide details of all expenses to be incurred in undertaking the various tasks by year. It was also to identify revenue/resources sufficient to cover planned expenses. In addition to federal housing funds, First Nations were directed to look for funding from band resources, local resources such as timber, straw, sand or gravel, labour, accommodation charges from individuals, private and public loan financing, rental regimes and other public programs.

The work plan and resource components were to be adjusted by First Nations until costs and resources are equal. If First Nations increased their housing expenditures through debt financing, they were advised to ensure future revenues would be sufficient to cover loan repayment costs in addition to ongoing maintenance, insurance, administration, renovation and construction equity.

There was also a component to link plans to job creation, training and economic development, and describe strategies to increase business opportunities within the community.

Finally, First Nations were expected to describe their governance structure as it related to housing. They were expected to describe their accountability mechanisms to community members and the Government. First Nations were expected to have transparent policies, programs and procedures and redress mechanisms.

First Nations that decided against opting into this process would continue operating under pre-1996 provisions of the INAC housing subsidy program. Their housing capital funding could only be used for construction, rehabilitation or renovation (and not for insurance, debt servicing costs, etc.), and would be released on a project-by-project basis.

While there were one-time additional funds attached to opting into the new process in 1996, the requirement that all plans be cost-neutral from an INAC perspective simply meant that INAC had positioned itself to emphasise First Nations raising revenues independently of the federal government. The process was designed to promote First Nations taking a greater role in their housing stock management, debt financing, and creating a culture of increased private ownership.

While there are positive aspects of this approach; namely the emphasis on First Nation management of housing, longer-term planning, and greater flexibility, there are some significant limitations. The direct financial benefits of opting into the new policy (beyond the annual minor capital allocation for housing), via-a-vis support for long-term planning, ended in by 2001. Since that time, there have been sporadic injections of funding for capacity development and planning, but no long-term or systematic initiative beyond the minor capital allocation itself. Additionally, the minor capital allocation stemming from opting into the policy has not adjusted with time, and First Nations receive the same rates as 20 years ago.

First Nations' development of short- or long-term housing plans is not intended to coordinate and allocate federal funding, beyond proposal-based initiatives. The Department considers them simply a planning tool for individual First NationsFootnote 19 with limited proactive measures to work with First Nations on helping them realise aspects of these plans. The planning-centred approach espoused by the new policy and its related guidelines were not designed as a tool for INAC to evaluate on an ongoing basis.

In other words, the extent to which this approach constitutes an actual policy is questionable, as it only captures a set of principles and an approach for annual allocations in place of exclusively relying on proposal-based projects in opting-in communities. The On-Reserve Housing Policy is more of a government position than an actual policy that articulates Terms and Conditions with First Nations. That position is that housing is the responsibility of First Nations with some support from INAC. In effect, what is referred to as the "policy" is a series of guidelines for opting into the "policy." There is no document that officially constitutes INAC's On-Reserve Housing Policy per se.

Recommendation 1: Engage First Nations to develop a clear departmental mandate to strengthen long-term capacity and governance with respect to housing. This engagement should be proactive, inclusive and meaningful, and with a view to better align departmental activities with the On-Reserve Housing Policy's stated principles of First Nation control, expertise, shared responsibilities, and increased access to private sector financing.

Additionally, the reactive nature of INAC's large funding injections since the development of this policy means there are wide variations between the application of approaches to housing on-reserve between INAC regional offices, with some taking a highly proactive approach with communities in helping them plan and navigate revenue generation, and others stating there is no authority to do so, and in some cases, variable desire on the part of First Nations to be engaged by INAC.

Recommendation 2: Provide INAC program officials with a strong and clear mandate and funding flexibility to proactively support individual First Nations and their designated professional organisations, where applicable, to better address their self-determined needs.

3.1.3 INAC, CMHC and Ministerial Loan Guarantees

Many First Nation housing managers and band councils, as well as federal employees, noted that the roles of INAC and CMHC can often be disjointed or overlapping. For instance, a First Nation must approach both organisations separately for funding support via proposals, handle two separate bureaucracies in terms of policies and procedures, and handle potentially different decision-making criteria when seeking funding for support. Within Budget 2016, there are calls for proposals with streams from both INAC and CMHC. Participants in this evaluation suggested it is unclear and ultimately inefficient when, for example, a First Nation seeking capacity development has to approach two organisations with two distinct processes. Interviewees gave recent examples of both federal organisations undertaking initiatives with the same purpose, ultimately overlapping one another and causing confusion among both government staff and First Nations.

The main component connecting the two departments is the Ministerial Loan Guarantees, which is INAC's loan guarantee to enable First Nations to borrow for the construction of homes. About 80 percent of these loans are through the CMHC, and the remaining 20 percent are through other financial institutions. While Ministerial Loan Guarantees are seen as a successful and essential component to support housing construction in general, a First Nation faces potentially inefficient processes in having to deal with two federal organisations to achieve one purpose. Key informants also expressed the perplexing nature of one federal government department insuring loans for another.

Additionally, while the Ministerial Loan Guarantee is an essential component of housing acquisition, particularly in relation to band-owned social housing, federal interviewees emphasised the need for INAC and CMHC to better consider the long-term implications of government-backed financing and the relative debt load and risk this presents to First Nations management capacity. Several key informants raised the concern that the ongoing use of Ministerial Loan Guarantees presents a growing financial liability to First Nations with respect to debt servicing as a proportion of their expenditures, particularly where rental revenue does not keep pace with the rising debt load. It was noted that some First Nations' debt loads were unmanageable, or would soon become unmanageable, due to outstanding mortgages.

Finally, it has been noted that current requirements for the acquisition of Ministerial Loan Guarantees make it hard for communities with previous defaults to access the program, thereby perpetuating the growing housing need in lower capacity communities.Footnote 20

Interviewees suggested there are questions with respect to the intent of Ministerial Loan Guarantees, and a lack of clarity on the extent to which they are intended to support home ownership, social housing, or both. One interviewee explained that the program was originally created to support home ownership, but has become a primary vehicle for social housing.

3.1.4 The Shelter Allowance Component of the Income Assistance Program

While not a part of the Housing Program, shelter is an allowable expense for Income AssistanceFootnote 21 recipients (above basic living cost allowances) on-reserve, and is intended to subsidise shelter costs, and mirror the policies of the province in which the reserve is located. INAC regional offices distribute funds to each First Nation for Income Assistance; however, the approach is variable between regions, and between communities for how the shelter allowance funds are administered vis-à-vis Income Assistance. This issue has significant implications on the affordability of housing for Income Assistance recipients, as well as on First Nation administrations trying to ensure their low-income members have adequate shelter.

According to INAC interviewees, regional allocations for shelter allowance do not adequately consider actual need, and do not keep pace with provincial policies. This has led to inequities between First Nations and between regions where, in some cases, shelter allowance allocation formulas only consider the number of income assistance recipients who live in CMHC-subsidised social housing backed by a Ministerial Loan Guarantee, whereas in other regions, the formula considers all income assistance recipients regardless of housing type. This, despite the fact that INAC's income support program is intended to mimic policies and rates of the province in which the reserve is located, and provincial allocations of costs related to shelter are applied regardless of housing type.

Additionally, there is variability between First Nations in how they administer the fund. They often include it in the income assistance payments to recipients (consistent with provincial practices). Other times, they retain the amount for rent or use the funds to pay mortgages to CMHC. This creates a risk that moneys intended for shelter allowance recipients subsidise housing for those not eligible for Income Assistance.Footnote 22

These issues are to be addressed in greater detail and with possible recommendations in the evaluation of Income Assistance, scheduled to be completed in June 2017.

3.1.5 Home-Ownership and Market-Based Housing

The Government of Canada plays a modest role in facilitating home-ownership and market-based housing on-reserve. Approximately a third of homes on-reserve is privately owned through various mechanisms described in Section 1.2.1. In high capacity communities with adequate revenue generation, use of revolving funds to back mortgages, and direct relationships with banks are common. Findings from case studies involving communities where there were direct relationships with banks, suggest this creates a far more sustainable housing portfolio in terms of risk and accountability for homes than regimes with exclusive or almost exclusive reliance on CMHC social housing. Ultimately, however, homeownership does not constitute a market in and of itself, and a traditional housing market is very rare on-reserve given the unique complexity of land holdings on reserve, as laid out in Section 3.1.1 regarding legal title and land interests. To this point, several interviewees questioned whether 'market-based' is an apt descriptor of home-ownership in most communities on-reserve, given the limitations posed by the Indian Act (such as the lack of traditional private property ownership and traditional, off-reserve abilities to buy, sell, and rent).

While non-members of a First Nation cannot hold "lawful possession" of reserve lands, under the Indian Act, they can obtain rights to use or occupy reserve land by entering into leases or acquiring permits or licenses. Leases, permits and licenses must be approved by the Band Council and the Minister and are issued by INAC. Rare examples like these are closer to the traditional market-based approach as off-reserve, in that there is an allowance for an exchange of services and revenues, such as property management regimes with rental units.

Where First Nations have the intent, capacity, governance, and means to facilitate homeownership, this is largely done independently of government,Footnote 23 although in many cases, government or government funded organisations, such as the First Nations Market Housing Fund or other organisations specialising in First Nations infrastructure, have supported reserves in navigating the legal and logistical processes necessary to achieve homeownership. This role of government is seen as appropriate (as will be discussed further in Section 4.2) and successful, as it focusses on capacity, knowledge, and testing the legal parameters of the current push for homeownership, juxtaposed against the sections of the Indian Act that deal with lands, which could not anticipate the current norms for land management and housing.

While interview and case study participants generally agreed that there is a desire to promote homeownership, they questioned whether there is adequate attention paid to strengthening the capacity of First Nation administrations to manage aspects of homeownership, and the extent to which there should be significant or immediate expectations for homeownership or housing markets given credit barriers faced by individual borrowers (such as lack of credit or high debt loads with excessive interest rates in cases of personal loan financing).

Interviewees questioned the necessity of the First Nations Market Housing Fund beyond its capacity initiatives, given the direct lending relationships between eligible First Nations and banks, the limited results of the initiative in terms of actual loan backing to date (185 loans backed by the Fund, including 96 new constructions), and the availability of the Ministerial Loan Guarantees.

Importantly, however, a third of First Nations to date have signed on to capitalise on support from the First Nations Market Housing Fund for capacity development and to strengthen the credit of individuals and band administrations to make homeownership and mortgage procurement more sustainable in the long term. While direct relationships with banks have been successful, the threshold for lending eligibility is lower in these cases because of Ministerial Loan Guarantees, thus, potentially making it easier to procure loans directly with banks than via the First Nations Market Housing Fund. In other words, consideration of the First Nation's ability to back-stop a loan is considered above the credit or means to pay of borrowers, presenting a liability to the band. According to fund managers, the First Nations Market Housing Fund works with a view to consider lenders the same way as they would be considered off-reserve. Given the considerable uptake by interested First Nations juxtaposed against the relatively low number of actual loan backings, it is possible that as governance and capacity on-reserve is strengthened, and as work is underway to improve the credit and debt management of individuals and band administrations, mortgages procured via the First Nations Market Housing Fund could increase.

Finally key informants suggested a continuum of priority for addressing housing needs that would start with health, safety and social needs; then land management and planning; and then homeownership and facilitating market-based housing where desired. Ultimately, home ownership and market-based housing may be seen as a viable solution to on-reserve housing issues only as part of a continuum of housing options. In many First Nation communities, there remains a strong need to build the capacity necessary to meet the preconditions of market-based housing, such as clear land tenure options on purchasing and transfer, a reasonably strong economy, and individuals with good credit, before such initiatives can be successfully implemented.

Critical preconditions to market-based housing include economic development and employment opportunities for First Nations community members, First Nations leadership support and commitment, skilled local trades workers, trained housing management, lender security, available and accessible financing, infrastructure financing, comprehensive housing policies and capacity for enforcement, and community involvement and education.Footnote 24

3.2 On-Reserve Housing in Practice

Despite significant investments, INAC's approach to on-reserve housing relative to its stated objectives presumes that First Nations have adequate governance, management and resource generation capacity to meet their housing infrastructure needs.

Housing funds received from INAC are generally put toward construction and renovation costs, combined with other revenue sources and sometimes project funds. This funding generally cannot cover, and nor was it necessarily meant to cover, costs associated with governance and capacity for adequate management of housing stock. These investments are not necessarily meant to meet the demand or need for construction or repairs to on-reserve housing. The implicit expectation set out in the "On-Reserve Housing Policy" is that First Nations procure resources from other means to meet their needs. However, revenue from other sources is often very limited, particularly in smaller communities with limited economic reach, and where the rate of deterioration and population growth outstrips the speed of construction and repair. These challenges are a much greater concern for communities without rental regimes or other own-source revenue. In other words, in communities with limited revenue generating capacity, it is not a reasonable expectation that they would be positioned to meet their housing infrastructure needs.