Evaluation of the Family Violence Prevention Program

Final Report

May 2017

Project Number: 1570-7/10024

PDF Version (379 Kb, 59 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings: INAC’s Role in Responding to Family Violence: Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings: Shelter Capacity and Performance (Effectiveness / Success)

- 5. Evaluation Findings - Prevention Programs: Design and Delivery

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Bibliography

- Appendix B – Annex Documents

List of Acronyms

| CMHC |

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation |

|---|---|

| FVPP |

Family Violence Prevention Program |

| INAC |

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

| NACAFV |

National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence |

| RCMP |

Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

Executive Summary

Evaluation of the Family Violence Prevention Program

The following executive summary provides a snapshot of the key elements of the Family Violence Prevention Program (FVPP) evaluation report. The reader may refer to the Table of Contents for areas of specific interest in the body of the report.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) has funded shelter support for Indigenous women dating back to the late 1970s beginning with shelter reimbursements for Indigenous women using provincial shelters. The Family Violence Prevention Program was introduced in 1988 as part of a pan-government Family Violence Initiative. The current evaluation by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) finds that work to reinforce the 41 shelter network (quality of service delivery) has been a key and important focus since the previous evaluation. However, the impacts for prevention programming could be enhanced though systematic attention and collaboration on learning, and expanding from the roster of mostly small-scale prevention approaches supported by FVPP to date.

FVPP is…

One of five social programs supported by INAC to ensure First Nations women, men and children are active participants in social development within their communities.

This ultimate outcome is buttressed by a mid-term result—specific to Child and Family Services and FVPP- which emphasizes the safety of men, women and children on-reserve.

The FVPP staff see themselves primarily as a conduit for funding community-based needs and remain at a distance from decisions about the daily operations of shelters and the design and roll-out of prevention programs. The FVPP staff, situated mostly at INAC regional offices, play an important review function of the dozens of proposals received annually for prevention funding.

This report presents the findings of an evaluation conducted by INAC's EPMRB. The evaluation assessed the relevance of FVPP, the intersections with federal partners, the emerging considerations, and the capacity of shelters and staff. It also reviewed the needs of clients, and the design and delivery of prevention programming. Finally, the report also examined possible intersections with other evaluations led by INAC.

The program funds and leads:

- Shelter Operations – the daily operating, infrastructure and staffing costs associated with running 41 women's shelter/safe house in/near First Nations.

- Prevention Programs – regions launch an annual Call for Proposals for on-reserve activities, while INAC Headquarters issues a national off-reserve call for proposals. Costs covered include activity costs, honorariums for instructors, counsellors.

- Policy Dialogue and Engagement – with Family Violence Initiative, federal, provincial and territorial advocacy groups, provincial counterparts, INAC programs.

The evaluation incorporated these lines of evidence:

- literature review;

- program document review;

- administrative and financial data analysis;

- on-line shelter survey (directors, staff and clients);

- key informant interviews; and

- site visits to four communities (Akwesasne, Mishkeegogamang (Ontario, Quebec); Fort Qu'Appelle (Saskatchewan), and Sampson and Sucker Creek (Alberta).

Outcomes - Relevance

The program remains relevant today in the wake of the launch of the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2016), results from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015) and the continued growth in incidence—on-reserve—of family violence in First Nations communities. Since the last evaluation (2012), INAC has made significant progress in consolidating funding support to 41 women's shelters across the country and expanding training opportunities for directors and staff (through Budget 2016 investments). The 2016 budget will also lead to the construction of five new shelters over three years.

INAC works at arm's length of shelter operations, instead enabling responsibility by band councils and shelter directors for key operational decisions on staffing, wages and service standards for clients.

Shelter Use and Capacity

The evaluation found that the shelter is often used for longer periods of time by clients—particularly in more remote communities—suffering from addictions, mental health issues and requiring other housing options. While not to the same degree as women, men also face violence from their intimate partners. According to an online survey of shelter clients, three out of four shelter users have used INAC shelters at least once before.

The evaluation found that many women transit to larger urban communities off-reserve and tap into provincially funded services, thus putting into question how INAC's shelter network intersects with other service providers and whether an approach of expanding geographical coverage is the answer.

The evaluation found, using the Family Violence service continuum, that most of FVPP's services fall into the category of "emergency response." The vast majority of shelter directors, staff, clients, and health service providers underscored the necessity for more transitional or second stage, post-crisis housing and to increase prevention and treatment programs for men and boys.

Prevention Program Design and Delivery

Layering prevention work onto the responsibilities of shelter directors and staff is a challenge given the time commitment they have already to crisis / shelter work with clients. As such, the evaluation found that more focused attention is required to staffing and support to prevention work, overall, in the program, and an effort to re-calibrate the overall funding structure to see more emphasis on community engagement and prevention.

The FVPP has made strides in engaging community stakeholders through its Call for Proposal process but it remains inefficient with respect to numbers of proposals that are reviewed for the very limited funds available for communities. The decision making on prevention rests with INAC regional offices. The evaluation found that a range of delivery mechanisms exist for prevention efforts, however, where aggregate models have been used - in particular Prevention Boards in Alberta and Manitoba - more success has been noted in deepening the knowledge and skill of prevention workers.

Efforts to include off-reserve organizations in a separate call for proposals are noted as a positive development. Very little evidence is available on community impacts of prevention programming due to the small-scale nature of most initiatives and lack of comparative data gathered at source.

Evaluation Recommendations

- Strengthen prevention activities by:

- Developing an inventory of existing prevention program delivery models (e.g., First Nation community-led, Tribal Council, other civil society organizations, theme-specific aggregate model) in order to encourage the application of good practices in each region.

- Drawing from the inventory exercise focus on leveraging existing expertise in order to establish aggregate models, similar to those functioning in Alberta and Manitoba, where appropriate.

- Providing Indigenous communities and their representatives with the tools that will help increase their capacity to plan, implement and oversee effective prevention activities.

- Strengthen FVPP's focus on increasing the accessibility and/or availability of transitional housing in strategic locations. Specifically:

- Reinforce data collection and reporting requirements to improve understanding of the existing levels of capacity in FVPP-funded shelter network.

- Consider repurposing select emergency facilities for transitional housing services as new data on shelter capacity becomes available.

- Adopt a more structured effort in support of mentorship and knowledge-sharing among the INAC supported network to enhance the capacity of shelter staff to meet the varied needs of community members.

- Increase Indigenous clients' access to the range of services available by:

- Building upon existing information sharing efforts aimed at coordinating the alignment of federally funded programs.

- Engaging in the strategic mapping of provincial and territorial services.

- Examine the requirements for, and draft a comprehensive prevention strategy to reach more adult men and male youth with culturally relevant prevention programming.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Family Violence Prevention Program

Project #: 1570-7/10024

1. Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan (MRAP) for the Family Violence Prevention Program (FVPP) has been developed in the context of the reform of First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS). While the FVPP and FNCFS are distinct programming activities at Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), it is important to note that planning and commitments made in this MRAP have been developed while accounting for the continuing evolution of FNCFS.

As well, the development of this MRAP has been informed by the ISC approach toward planning and reporting as seen in, for example, the Departmental Results Framework and the Performance Information Profile for the Family Violence Prevention Program. Specifically, both this Management Response and Action Plan and the program's logic model and associated performance measurement (e.g., indicators) are closely aligned. Future monitoring of the program's performance and evolution will come from the perspective of both regular Management Response and Action Plan updates to the Department's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee and through the program's performance measurement approach.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

1. Strengthen prevention activities by: a) Developing an inventory of existing prevention program delivery models (e.g., First Nation community-direct, Tribal Council, other civil society organizations, theme-specific aggregate model) in order to encourage the application of good practices in each region. |

We do concur. a) The ISC Family Violence Prevention Program will collaborate with partners such as First Nations communities, civil society organizations, provinces/ territories and other federal programs to document best practices in family violence prevention. |

Assistant Deputy Minister Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships |

a) Start Date: Completion: |

b) Drawing from the inventory exercise by focusing on leveraging existing expertise in order to establish aggregate models, similar to those functioning in Alberta and Manitoba, where appropriate. |

b) As part of documenting best practices in Family Violence Prevention (as seen in a) above), the FVPP will recommend to stakeholders that they explore the potential for establishing region-specific aggregate models for prevention activities. | b) Start Date: Completion: |

|

| c) Providing Indigenous communities and their representatives with the tools that will help increase their capacity to plan, implement and oversee effective prevention activities. | c) Work with ISC-supported and mandated organizations to enhance the capacity of staff in FVPP-supported shelters in their efforts to:

|

c) i) Start Date: Completion: A key example with target date March 31, 2019 is the National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence (NACAFV) project to enhance its tools available online. Through the NACAFV website and through social media, national online-discussion forums and groups, research tools such as scales and indices, region-specific resources (e.g., information on provincial legislation and regional organizations) will be developed. ii) Start and Completion dates: The program’s data collections are reviewed and revised annually through the Department’s Reporting Guide development cycle. The most recent review was in summer 2018. It will be finalised in September 2018. |

|

2. Strengthen the FVPP’s focus on increasing the accessibility and/or availability of transitional housing in strategic locations. Specifically: a) Reinforce data collection and reporting requirements to improve understanding of the existing levels of capacity in FVPP-funded shelter network. |

We do concur. a) In order to better understand the existing levels of capacity across the FVPP-funded shelter network, the program updates annually its Data Collection Instruments to highlight areas related to capacity levels. For example, the program collects information related to capacity levels (e.g., requests for shelter services vs. turnaways). Information such as this contributes to the use of best practices and the documentation of shelter needs. |

Assistant Deputy Minister Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships |

The program’s data collections are reviewed and revised annually through the Department’s Reporting Guide development cycle. The most recent review was in summer 2018. It will be finalised in September 2018. |

| b) Consider repurposing select emergency facilities for transitional housing services as new data on shelter capacity becomes available. | b) The program will collaborate with ISC-funded shelters and associated organizations (e.g., First Nations) to establish a strategy for repurposing parts of existing emergency facilities where appropriate and feasible given contextual factors and existing resources. | b) Start Date: Completion: |

|

| 3. Adopt a more structured effort in support of mentorship and knowledge-sharing among the ISC supported shelter network to enhance the capacity of shelter staff to meet the varied needs of community members. | We do concur. To support continued enhancement of mentorship and knowledge sharing among ISC-funded shelter staff, the program will utilize the best practices identified in 1a above in order to develop a strategic approach to supporting mentorship and knowledge sharing among the ISC-supported shelter network. |

Start Date: Completion: |

|

4. Increase Indigenous clients’ access to the range of services available by: a) Building upon existing information sharing efforts aimed at coordinating the alignment of federally funded programs. |

We do concur. The ISC Family Violence Prevention Program will: a) i) work closely with Status of Women Canada to ensure that the National Strategy to Address and Prevent Gender-Based Violence includes Indigenous perspectives as it is a target group under the Strategy. The first deliverable to be supported by ISC is the Knowledge Centre (SWC lead). ii) ensure strong ISC representation on the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Working Group for the Family Violence Initiative. |

Assistant Deputy Minister Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships |

a) i) Start Date: Completion: ii) Start and Completion dates are not applicable as the Family Violence Initiative (lead by PHAC) is ongoing. |

| b) Engaging in the strategic mapping of provincial and territorial services. | b) seek opportunities to collaborate with provinces and territories to develop a "snapshot" report documenting available services for family violence protection and prevention, whether provincial, territorial or federal, and their availability/ proximity to Indigenous clients. This effort will support initiatives designed to enhance access to these services. | b) Start Date: Completion: |

|

| 5. Examine the requirements for, and in cooperation with First Nations, draft a comprehensive prevention strategy to reach more adult men and male youth with culturally relevant prevention programming. | We do concur. The program will work with First Nations, other federal departments, and regional and national organizations involved in supporting Indigenous people experiencing family violence issues to develop and implement a strategy to address the needs of Indigenous men and boys, both as victims of family violence and as perpetrators. |

Assistant Deputy Minister Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships |

Start Date: Completion: |

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This is the final report of the evaluation of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Family Violence Prevention Program (FVPP). It was conducted as part of the Department's approved Five Year Plan on Evaluation and Performance Measurement Strategies (2015) and in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results. While informing policy, the evaluation primarily aims to address the relevance and performance of the following program authority: Contributions to support culturally appropriate family violence shelter and prevention services for Indian women, children and families resident on-reserve.

The report presents findings covering the 2012-13 to 2015-16 fiscal year periods. The purpose of the evaluation is to provide a credible, reliable and timely assessment of the FVPP.

Structure of the Report

This report is divided into six key sections. Section 1 summarizes the federal response to family violence on-reserve, including a profile of the FVPP. Section 2 details the methodology used to conduct the evaluation. Sections 3 to 5 present evaluation findings, and Section 6 discusses the evaluation's conclusions and recommendations.

1.2 Federal Context and Program Profile

Family violence is a broad concept that includes the abuse of children, youth, intimate partners and elders. It includes physical assault, intimidation, mental or emotional abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, deprivation, and financial exploitation. It is a complex social problem with serious consequences for individuals, families and society.Footnote 2

1.2.1 Federal Context

Indigenous women make up four percent of Canada's female population; however, they represent 16 percent of all murdered women and 12 percent of all missing women on record (1980-2012).Footnote 3 On August 4, 2016, the federal government launched the independent national Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The mandate of the inquiry is to "examine and report on the systemic causes of all forms of violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada and look at patterns and underlying factors."Footnote 4 The launch of the inquiry is an important step in the national recognition of the long-standing cycle of violence and harm experienced by Canada's Indigenous women and girls, and a social problem that affects Indigenous communities across the country.

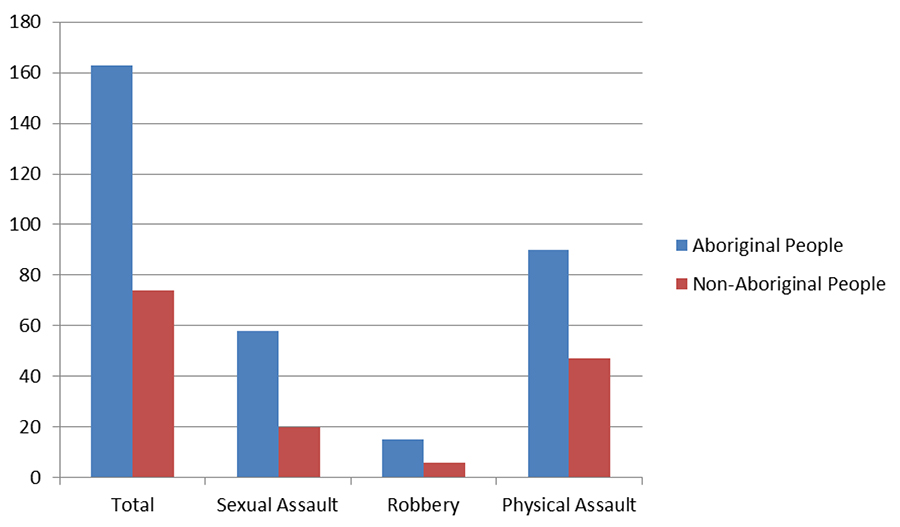

On June 28, 2016, Statistics Canada released a study entitled Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014. The study, which highlights the continued relevance of delivering family violence prevention in Indigenous communities, focused on the prevalence of various types of victimization and the characteristics of victims, such as gender, age and other risk factors. The study also notes that the overall rate of violent victimization of Indigenous women is 2.2 times higher than that of non-Indigenous women (i.e., 163 versus 74 incidents per 1000 people). This is illustrated in Graph 1.Footnote 5 The study notes that prior to age 15, Indigenous women are nearly three times as likely as their male counterparts to experience both physical and sexual maltreatment, i.e., 14 percent compared to five percent.Footnote 6

Figure 1: Violent Victimization Incidents Reported by Indigenous (Aboriginal) People and Non-Indigenous (Aboriginal) People (By type of violent offence, provinces and territories. Rate per 1,000 population aged 15 years and older)

Note: All differences between Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people are statistically significant, except for robbery.

Source: "Victimization of Aboriginal People in Canada," 2014 Statistics Canada Study.

Text alternative for Figure 1: Violent Victimization Incidents Reported by Indigenous (Aboriginal) People and Non-Indigenous (Aboriginal) People (By type of violent offence, provinces and territories. Rate per 1,000 population aged 15 years and older)

Graph 1, illustrates the Incidents of Violent Victimization reported by Aboriginal People and Non-Aboriginal People (By type of violent offence, provinces and territories. Rate per 1,000 population aged 15 years and older). As for the number of "Total" incidents of violence reported, there were 163 for "Aboriginal People" and 74 incidents for "Non-Aboriginal People"; under "Sexual Assault," "Aboriginal People" had reported 58 incidents, and "Non-Aboriginal People" reported 20; as for "Robbery," "Aboriginal People" had reported 15 incidents, and "Non-Aboriginal People" had reported 6; and for "Physical Robbery," "Aboriginal People" reported 90 incidents, "Non-Aboriginal People" reported 47.

The study also found that Indigenous women are more than twice as likely to experience the most severe forms of physical spousal violence. Over 48 percent reported being sexually assaulted, beaten, choked, or threatened with a gun or knife.Footnote 7 As well, an Amnesty International 2014 Report found that there was a "disproportionate incidence of violence against Indigenous women in Canada."Footnote 8 In a 2009 government survey of the ten provinces, Indigenous women were nearly three times more likely than non-Indigenous women to report being a victim of a violent crime."Footnote 9

Federal Government Response

In general, the chronology of the federal government's engagement and response to family violence in Indigenous communities dates back almost 40 years. Table 10 in Appendix B provides a full overview of the federal government response. Some milestones include:

- 1978: INAC begins its involvement in family violence prevention by providing shelter reimbursements to some provincial governments and to the Yukon territorial government.Footnote 10

- 1988: Start of the Family Violence Initiative and a supporting network of 13 federal government departments.

- 1998: Statistics Canada releases its first Family Violence in Canada study.

- 2016: Federal Budget provides new funds to address Family Violence:

- $10.4 million over three years for the renovation and construction of five new shelters for victims of family violence in First Nation communities; and

- $33.6 million over five years and up to $8.3 million ongoing in additional funding to better support shelters serving family violence victims in First Nations communities, including some attention to training initiatives.

The federal response to family violence, led and coordinated through the Public Health Agency of Canada led Family Violence Initiative, has varied.Footnote 11 Table 1 highlights the Family Violence Initiative and the partner departments/agencies involved.

The Family Violence Initiative

|

Partner Departments/Agencies

|

Over the years, the FVPP has evolved to more effectively respond to the complex challenge affecting the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples. During the period covered by the evaluation, the 2014 introduction of Canada's Action Plan to Address Family Violence and Violent Crimes Against Aboriginal Women and Girls provided the FVPP with some fundsFootnote 12 increasing its annual budget allotments to approximately $33 million per year; this supported the expansion of the programs' work to fund off-reserve initiatives to address family violence (See Table 10 in Appendix B).

1.2.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The expected results of the FVPP are articulated in the Social Development Performance Measurement Strategy under the "People" Strategic Outcome; there are five programs in total nested under this umbrella strategy, including FVPP.Footnote 13 This evaluation focused primarily on the immediate outcomes related directly to FVPP:

Immediate Outcomes

- Men, women and children in need or at-risk have access to and use FVPP prevention and protection supports and services;

- Existing prevention projects' effectiveness is maximized;

- Existing levels of shelter capacity is sufficient to meet FVPP objectives; and

- The effectiveness of partnerships and coordination is maximized.

The scope of the evaluation was expanded to look at the linkages with Child and Family Services as included in the Intermediate Outcome: Men, women, and children are safe.Footnote 14

1.2.3 Program Governance, Key External Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The FVPP is managed by the Children and Families Branch, Education and Social Development Program and Partnerships Sector. INAC provides operational funding for shelters to First Nations in each province and in the Yukon Territory. These funds are used to support the operation of shelters that primarily serve First Nation women and children on-reserve.

In 1992, under an agreement with the Province of Alberta ("Arrangement for the Funding and Administration of Social Services"), INAC has the authority to reimburse costs for off-reserve, provincially funded shelter services used by on-reserve residents, while the province pays per diems to the shelter for all women who used the on-reserve shelter but are not residents of the reserve.

In the Yukon where there are no reserves, the FVPP reimburses the territorial government for shelter services. All First Nations clients are considered 'ordinarily residents on-reserve' in this territory and have access to all shelters and their services.

Key External Stakeholders

INAC's external stakeholders include:

- Federal government Family Violence Initiative partners (Table 1). Consultations occur with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) on shelter funding proposals; with Health Canada and the Assembly of First Nations on the First Nations Mental Health and Wellness Continuum Framework; and with Status of Women on the Gender Based Violence strategy.

- Eligible Recipients for FVPP Funding: First Nations; tribal councils; other aggregations of First Nations approved by Chief and Council or, an authority, board, committee or other entities providing family violence protection and prevention services.

- The National Aboriginal Circle Against Family Violence (NACAFV): A national Indigenous organization to which the FVPP provides core and project-based funding. The organization is mandated to provide support to INAC-funded shelter directors and front-line shelter personnel.

Beneficiaries

- The Indigenous men, women and children living on-reserve and off-reserve affected by family violence.

1.2.4 Program Resources

The FVPP has two key program components for which it provides funding and which focused on protection and prevention.

- Protection (approximately 75 percent of the budget): Funding for the day-to-day operations of a network of shelters that provide services for women and children living on-reserve in provinces and in the Yukon. The funding envelope for protection includes the salaries of shelter directors and staff who run the network of INAC facilities and offer varying degrees of prevention programming at the shelter or in the community, as part of their regular work duties;Footnote 15 and

- Prevention (approximately 25 percent of the budget): Funding for annual or multi-year community-driven prevention projects such as public awareness campaigns, conferences, workshops, stress and anger management seminars, support groups, and community needs assessments on- and off-reserve.

INAC's 2016-17 Report on Plans and Priorities states that there are 12 Human Resources (full-time equivalents). However, the regions, as indicated in the 2012 INAC evaluation, do not have a full-time equivalent dedicated to the FVPP as they manage other programs, for instance, the First Nations Child and Family Services.

Table 2 outlines the resources.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote | Actual | Planned | ||||

| Vote 1 Personnel Salary and Operation and Maintenance | 121,044 | 995,955 | 963,890 | 1,007,245 | 1,764,099 | 4,852,234 |

| Vote 10 Grants and Contributions | 33,969,978 | 31,428,789 | 31,036,124 | 32,007,889 | 35,705,393 | 164,148,173 |

| Non-budgetary expenditures | 12,767 | 146,246 | 144,451 | 143,877 | 281,010 | 728,352 |

| Total | 134,103,789 | 32,570,991 | 32,144,466 | 33,159,012 | 37,750,502 | 169,728,761 |

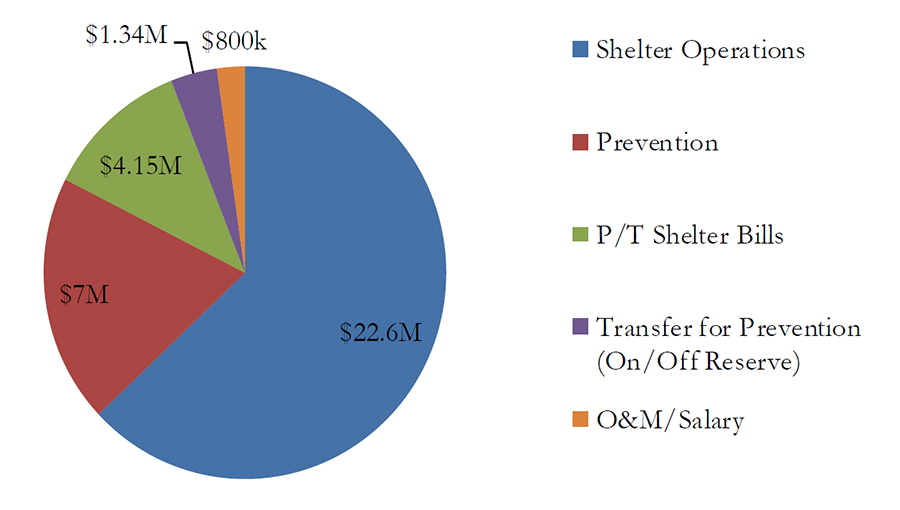

Figure 2: FVPP total allocations 2016-2017 (36.5M)

P/T: Provincial/Territorial

O&M: Operations and Maintenance

Text alternative for Figure 2: FVPP total allocations 2016-2017 (36.5M)

Pie chart illustrates the total Family Violence Prevention Prorgam (FVPP) allocations for 2016-2017 in the various program areas: In terms of allocations for "Shelter Operations" $22.6 million; the allocation for "Prevention" was $7 million; the allocation for "P/T Shelter Bills" was $4.15 million; the allocation for the "Transfer for Prevention (On/Off Reserve)" was $1.34 million; and finally the allocation for "O and M/ Salary" was $800 thousand.

Funds for the FVPP are primarily disbursed at a regional/community level by INAC regions:

- Funding for the operation of shelters is based on a national proposal-based funding formula, developed in 2006 and designed to establish regional allocations and shelter operating budgets that are fair and consistent across Canada. Shelter allocations consider the size of the shelter, its province of operation, geographic location and, where applicable, the costs associated with remoteness and emergency needs.

- Family violence prevention activities are funded on a project basis in most regions, with some INAC regions placing emphasis on selecting projects based on partnerships and maximizing reach.Footnote 18

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined FVPP activities between 2012-2013 and 2015-2016. Terms of ReferenceFootnote 19 were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 22, 2016. Fieldwork was conducted between November 2016 and January 2017.

2.2 Evaluation Questions

The evaluation issues of Relevance, Design and Delivery, and Performance were addressed under the following questions:

- Is the FVPP an appropriate response to family violence in Indigenous communities?

- What are the key issues that the FVPP should address in order to meet its objectives in response to the 2012 INAC evaluation recommendations?

- Design and Delivery: Are shelters meeting the needs of clients in terms of access and service?

- Performance: How effective are prevention programs? What opportunities exist to improve their impact?

- Does the current FVPP funding structure contribute to efficient program delivery?

- To what extent is the FVPP achieving its expected outcomes (impacts on those affected)?

2.3 Evaluation Methodology and Data Sources

Evaluation findings and observations are based on the following lines of evidence: media and literature reviews; document, data and file reviews; key informant interviews; site visits; and an online survey for shelter directors, staff and clients. The literature review compiled in support of the evaluation covered a cross-section of national data and some international literature from both academic and practitioners' sources (Bibliography in Appendix A). The total number of individuals interviewed by the evaluation team was 91 (See groupings in Table 3).

| Organization Type | Number of Interviewees |

|---|---|

| National Indigenous Organizations | 7 |

| INAC Headquarters | 7 |

| INAC Regions | 11 |

| Other Federal Departments | 7 |

| Provincial Governments | 5 |

| Site Visit Interviews (met with four communities in total) | 47 |

| First Nation's Community Organization Representatives (phone outreach) | 7 |

| Total: | 91 |

Four site visits (Ontario = two; Saskatchewan = one; and Alberta = one) were undertaken. The sites were identified in collaboration with INAC's FVPP officials, with the goal of reviewing existing FVPP operations within or close to Indigenous communities, and examining the FVPP's role and experience at each site (See Table 4).The site visits included focus group sessions with FVPP service providers, interviews with provincial government officials, Indigenous organizations, community service providers and clients.

| Location | Rationale for Selection of the Four Site Visits |

|---|---|

| Ontario (Akwesasne Mohawk Nation) Iethinisten:ha Women's Shelter | Opened in 1993. Considered by many to be a high-capacity and 'best practice' model. The Shelter is well-supported by the community and is unique in that it serves multiple jurisdictions (Ontario, Quebec and the United States of America). |

| Northern Ontario (Mishkeegogamang First Nation) Mishkeegogamang Safe House | Recently opened (2016) after a period of closure due to management issues. The shelter is road accessible but otherwise relatively isolated. It was selected to underscore the challenges of delivering support in a more isolated setting. |

| Saskatchewan (File Hills Qu'Appelle Tribal Council) Fort Qu'Appelle Safe Haven | Opened in 1995. The shelter has helped to identify changing needs and issues in the area. It is recognized for having developed and delivered a prevention model that is based on cultural and traditional family values. |

| Alberta (Three Eagles Wellness Society) Sampson/Sucker Creek First Nations | Established in 1991. The Society is a FVPP fund recipient, acting as an intermediary with all three Treaty areas in Alberta. It is an example of a "Prevention Board" that supports the identification of needs and delivery of family violence prevention programs in these communities.Footnote 20 |

Seventy-five surveys were completed by shelter directors, staff and current clients of shelters; some were completed online and some on paper (See Table 5).

| Online Survey | Number of Respondents | Response Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Shelter Director | 24/41Footnote 21 | 59% |

| Shelter Clients | 23 | N/A |

| Shelter Staff | 28/41Footnote 22 | 68% |

| Total: | 75 | N/A |

Each of the 41 INAC-funded facilities received electronic links for all three individualized surveys. Staff, excluding shelter directors, were asked to complete one survey per shelter as a "team."Footnote 23 Directors provided paper copies to current clients in-house and requested their consent to participate.Footnote 24

2.3.1 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

Considerations

A working group was established composed of representatives from key government departments engaged in the Family Violence Initiative, with whom INAC maintains a regular contact.Footnote 25 It also included a representative from an external advocacy organization.Footnote 26 The group reviewed and commented on the evaluations' findings, conclusions, and recommendations. Two meetings of the working group were held.Footnote 27

Strengths

The online survey, using a simple web-based platform, reached INAC's entire network of 41 shelters. Where requested, paper copies were also made available to shelters. The use of an on-line survey proved effective as it allowed the evaluation to gather information directly from shelter directors, staff and shelter clients. Receiving feedback from shelter clients was particularly important because previous evaluations had not collected input from this group. In addition, FVPP program officials administered a survey (2016) as part of overall program data collection efforts. This survey supported data triangulation, as it included details on shelters' needs, as well as the role of the NACAFV in ensuring better training and supports for Indigenous communities.

Limitations

Data: Inconsistent reporting on shelter usage; lack of information on proportion of beds used for emergency versus transition purposes; and, on length of stay of clients.Footnote 28

Number of Site Visits: Given the allotted time for data collection, only four sites were visited (Table 4). A broader sample of shelters and prevention activities would have been advantageous to compare, particularly in how they relate to provincial networks, engage communities.

Site Selection: The selection of the site visits was not randomized. To compensate for the limited number of site visits, communities employing different prevention approaches were selected.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch led the evaluation study. To complement its activities, the Branch engaged Auguste Solutions and Associates Inc., an Indigenous private sector consultancy experienced in program evaluation and INAC social programming. Quality assurance was ensured by an internal branch review process, the use of a working group to provide guidance and rigorous review, and through an internal departmental review and approval process.

3. Evaluation Findings: INAC’s Role in Responding to Family Violence: Relevance

This section explores the relevance of the program. It looks at whether the FVPP is an appropriate means of responding to family violence in Indigenous communities. It also looks at the key issues that the FVPP should address in order to meet its objectives in response to the recommendations of the 2012 Family Violence Prevention Program Evaluation.

3.1 INAC's Response to Family Violence

Finding 1: There remains a strong need for continued focus by INAC—and other federal government partners—on the issue of family violence. The FVPP draws from its cumulative experience and network to address the significantly higher levels of family violence incidences occurring in First Nations communities.

The evaluation found that there is a strong continued need for the FVPP (e.g., the provision of funding for emergency shelter responses to family violence experienced by First Nations people and opening up avenues for dialogue about prevention). There also continues to be a need for a range of prevention activities. Program officials, since the last FVPP evaluation (2012), have undertaken 36 on-site shelter visits. The program has also undertaken the development of shelter work plans/prevention project work plans with the goal of assessing shelters' capacity and needs.

The relevance of INAC-funded programming could be optimized further by a more thorough understanding of the systemic causes of family violence and an enhanced connection to other federal, provincial and territorial programs and services that are mandated to work with Indigenous women, children and men. Interviews with other government departments, and internally within INAC, highlight that there are several multi-sectoral prevention approaches currently being applied to address and prevent family violence.

The evaluation found that current shelter operations program funding ($24 million per year, on average) represents about 75 percent of overall FVPP funding. Meanwhile, available funds to respond to prevention-specific needs equates to $8 million per year (on average, 25 percent of overall FVPP funding). The consensus amongst those interviewed during this evaluation is that:

- The crisis response provided by the shelters is essential; and, the importance of shelters is reinforced by the 2016Footnote 29 Federal Budget announcement of funding for the construction of five new shelters, which will raise the number from 41 to 46 over the next three years;

- The need for prevention, considered the only viable long-term solution to reducing violence; and,

- Data on FVPP-funded prevention program impacts is in limited supply thus contributing to uncertainty over which funded-approaches work the best in achieving long-term results.Footnote 30

INAC officials are sensitive to the current funding proportionality (protection vs. prevention), however, interviewees suggested that their role is to support the availability of shelter services and, as funding providers, to respond to community-articulated needs. While there is often overlap between prevention and protection, it is clear that the FVPP focusses the largest portion of its annual funding envelope on shelter operations. In essence, the relevance of the FVPP is as well heightened by the sine qua non nature of protection in confronting family violence: ensuring shelter and protection of life by providing safety for victims of abuse. Thus, the primary orientation of program funding towards protection is apparent given that, by its nature, real-time violence requires immediate attention to avert further harm.

The evaluation found that shelters supplement prevention services by leveraging the resources of other stakeholders, including community-based prevention activities, the goal of which is to reduce the incidence of family violence. The relevancy of the FVPP is increased as there appears to be less focus on prevention because of limited funding and varying degrees of community capacity to plan and implement such programs. From a program planning perspective, the results associated with prevention programs are more difficult to track over time in an efficient, consistent manner across First Nations' communities that are using, for the majority of instances, a wide-range of small-scale and disjointed methods. However, notwithstanding the fact that prevention has the potential to produce better outcomes, it is also clear that early detection of family violence could lead to remedies and interventions that will prevent further abuse by holding the abuser accountable and helping to mitigate the consequences of family violence.

The FVPP funding levels for prevention which have remained steady since 1991 ($7 million a year), points to relevancy. The cost of delivering these programs has not kept pace with the Consumer Price Index inflation rate (36 percent) that has occurred since program inception. This indicates that budget allotments do not appear to consider population growth among the fast-growing First Nation communities.Footnote 31

3.1.1 Factors Contributing to Family Violence in Indigenous Communities

As noted in the introduction (Federal Context 1.1.2), Indigenous peoples in Canada face a much higher rate of violence in their daily lives and over their lifetime compared to non-Indigenous Canadians. The causes of family violence are complex and, even more so for Indigenous communities. The literature reviewed for the evaluation illustrates the areas impacting the occurrence of family violence and encompass the social determinants of health, including economic and social conditions and their distribution among the Indigenous population.

A range of factors can be summarized under two key areas—social and cultural impacts. These include poor socio-economic conditions, high rates of alcoholism and substance abuse, and sub-standard housing. According to the literature review, the most common unifying experience across Canada's First Nations people is the trauma left by the residential school legacy (Anderson, 2010), which has generated cycles of intergenerational violence.Footnote 32 Racism, colonization and residential schools have also had long-term impacts, including a breakdown in connectedness to land and culture, and the impacts of inter-generational trauma on social relationships.Footnote 33

Lack of adequate housing, in general, appears to be a contributing factor to the occurrence of family violence. Crowded living conditions compound the health and violence challenges faced by Indigenous peoples. A safe home requires affordability as well as enough space for the family.

3.1.2 Statistical Knowledge Base

Finding 2: Reliable statistical information on the incidence of family violence is challenging to gather as violence is under-reported. The challenge is more acute in Indigenous communities due to multiple barriers to accessing services. These information gaps impede a full understanding of the changing contributing factors and attitudes towards violence.

The literature review revealed that there is limited to no data about violence facing individuals living on-reserve. This is confirmed by such studies as The Transitional Home SurveyFootnote 34, and other wide-ranging surveys of Canadians, including Indigenous people living off-reserve.Footnote 35

Current Statistics Canada data is obtained through police-reported statistics and self-reported victimization surveys. It is important to note that family violence often goes under-reported or unreported for various reasons, including stigma faced by the victims, perceived influence or, mistrust of officials (Child and Family Services or police), manipulation by the perpetrators over younger victims.

The evaluation found that considering the proportion of Indigenous women/people facing domestic violence, the FVPP's relevancy is compromised by a fundamental challenge to its delivery: the lack of reliable statistical information, which appears to limit the FVPP's ability to adjust to different contributing factors and realities emerging at national, regional and community levels.

3.1.3 Jurisdictional boundaries in provision of family violence supports

Finding 3: There is a tendency for Indigenous women to transition to off-reserve services to seek support.

According to the literature review, there are 627 women's shelters (including provincial and territorial funded shelters) in Canada. This shelter network, both on- and off-reserve, includes crisis response shelters, second-stage (transition) housing and other facilities that provide services to women and their children fleeing family violence. In most provinces and territories, services are provided to Indigenous women and children both on- and off-reserve. Data from the 2014 Transition House Survey indicates that around eight percent (49 shelters) of shelters serve mainly on-reserve residents. While three percent (17 shelters) serve exclusively on-reserve clients, five percent (32 shelters) were located on-reserve and some reported also serving women off-reserve. Twenty-seven percent (169 shelters) that primarily serve off-reserve residents also serve people who live on-reserve.

When responding to the online survey administered as part of the evaluation, shelter workers in INAC funded facilities suggested that many women seek refuge elsewhere (beyond their resident First Nation community) for a variety of reasons.Footnote 36

To validate this information, evaluators visited shelters in "gateway" communities, which facilitate easier access to more remote areas of Ontario in order to understand why and how Indigenous women move from northern, more remote communities to southern shelters, most often to non-INAC funded shelters. Information gathered from these gateway communities indicate that almost all of the shelter clientele arrive from First Nations' communities in remote northern Ontario where emergency services may not be available or where the women rather choose to leave, corroborating reasons provided through the INAC staff-administered survey. Said a shelter manager,

"We serve 26 communities, 19 of them are fly in communities. The ones accessible by road—we use taxi transportation to bring them here. We know where the federal shelters are—but sometimes the women just want to leave and come here for their safety."

3.1.4 Responsive Model and Mechanism

Finding 4: No inventory or mapping of services accessible off-reserve is available to help support strategic program decisions about the construction of new shelter or protection-oriented services.

Since the last evaluation, the program has worked to support the expansion of its shelter network guided by a proximity analysisFootnote 37 to ensure the widest possible coverage of First Nation's communities served by the existing INAC-funded shelters. However, considering the trend of women desiring to leave their communities and seeking a range of social services off-reserve, the overlay of strategic funding to shelters should not only be guided by coverage among the First Nations, but also by the existing services provided by other off-reserve jurisdictions, as this will ensure that a complementarity of services and cost-efficiencies are arrived at. This may eventually allow for a proportion of existing funding levels to move towards prevention. This re-balance or shift could only occur where off-reserve emergency shelters may be in closer proximity for some First Nations, and/or transportation supports are provided to guide women to nearest available/existing shelter services.

In total, there are 617 First Nations' communities and often times access to both these networks of shelters proves to be an issue. INAC has estimated that 87 percent of the registered Indigenous population is covered by its shelter network (meaning 528 bands either have a shelter located on-reserve or have road access to one of the INAC-funded shelters. (See Table 9 in Appendix B for more detail).

While collaborating with CMHC, the Department maintains, as a priority, its response to community-driven proposals to build shelters in their communities; now with the 2016 Federal Budget, the FVPP is expanding its shelter network.Footnote 38 Often, a shelter is prioritized by First Nations' community officials as a tangible and needed response to immediate safety concerns of victims; it appears, however, that perhaps this is done without weighing other options of services available within close proximity. The current role of INAC is to maintain a supportive role in helping those communities fulfill their identified priorities. While not assuming a challenge function, exploiting the possibility of mapping services by looking at the balance of other service providers available in the vicinity could then free up some funding for other equally valuable family violence responses along the Family Violence continuum.Footnote 39

In an era that is now characterized by advances in communications, technology and transportation, a First Nation community's request to build a new shelter within its territory provides a good opportunity, not only to close the distance gap with other unserved First Nations but also to undertake an inventory of support services that are available in neighbouring vicinities, with support for transportation factored in accordingly.

3.2 Working Relationship with Other Federal Departments

In response to a key 2012 INAC FVPP evaluation recommendation, i.e., "strengthen linkages with other departments to ensure that projects are delivered in a coordinated manner to improve access,"there is ample evidence suggesting that the FVPP has since worked to maximize its partnership opportunities within the Family Violence Initiative. For instance, in terms of supporting women's shelters on-reserve and providing prevention programming for on-reserve and off-reserve activities, INAC is the lead.

3.2.1 Horizontal Information-Sharing

Finding 5: INAC is a part of the federal Family Violence Initiative, which serves primarily as an information-sharing platform. There is some evidence of program collaboration among other departments but it appears to occur mostly on an ad-hoc basis.

INAC officials meet on a quarterly basis with other Family Violence Initiative departments, as convened by the Public Health Agency of Canada.Footnote 40 According to participants, the primary function of the Family Violence Initiative is information-sharing, which to date, has proven valuable.

Evaluators found some evidence, which demonstrates that during the period covered by the evaluation, the Family Violence InitiativeFootnote 41 forum helped enhance program collaboration. Examples of collaboration include:

- Development of a legal toolkit for women in shelters. INAC funded consultations, and Status of Women funded the development of a toolkit. The Department of Justice funded the in-person training for the staff at 41 shelters.(2014)

- Public Safety worked with Health Canada and the RCMP to determine which First Nations communities might benefit from the Community Safety Planning initiative.(2015)

- Health Canada and the Assembly of First Nations worked together to introduce a First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework. INAC is a part of the implementation team and there has been sharing among Family Violence Initiative partners.(2015)

- INAC and CMHC reviews proposals for shelter site selection and renovations. (ongoing)

The Family Violence Initiative collaboration is occurring primarily in the National Capital Region. The evaluation did not probe to determine whether collaboration occurs among federal counterparts located in regions. This issue was highlighted in a number of interviews with key informants:

"There needs to be an ongoing mechanism to get all federal departments who are addressing family violence together and making sure that the funds are being spent effectively and sharing where we can."

3.2.2 Relationship Among Federal Departments on Family Violence

Finding 6: Key partners are concerned about improving alignment among the full complement of federally-funded programs addressing family violence in Indigenous communities.

The Prime Minister has identified reconciliation with Canada's Indigenous people as an overarching theme of his government's approach, and underscored among his Cabinet the importance of addressing recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.Footnote 42 Footnote 43 The Commission's "Calls to Action" feature several recommendations related to family violence, including calls to address gaps in mental health services, reduce the number of Indigenous people in custody, and create culturally relevant healing centres.

Another instance of federal departments' opportunity to strengthen their relationship is the five-year, Status of Women-led "Canada's Action Plan to Address Family Violence and Violent Crimes Against Aboriginal Women and Girls" (Economic Action Plan 2014). Federal departments collaborate in terms of support and coordination of efforts, sharing of information and best practices. The Action Plan's three pillars (Preventing Violence, Supporting Aboriginal Victims, and Protecting Aboriginal Women and Girls) indicate the Government of Canada's specific focus on addressing violence that is perpetrated against Indigenous women and girls. Through the Action Plan, Heritage Canada transferred responsibility and funding for off-reserve proposals in family violence prevention to INAC in order to better synchronize efforts. (2014)Footnote 44

The interviews with other federal government partners underscored a willingness among working level public servants to share knowledge and practices, however, rarely has it led to much more than cost-sharing agreements around small-scale programs and information-sharing on family violence statistics and programming. This is due to the departmental guidelines and Terms and Conditions, approved by the Treasury Board.

Most interviewees are calling for a major "re-think" of how government works on this issue in order to be more impactful in reducing the incidence of family violence in Indigenous communities. The preferred approach is a combination of improved alignment and a more strategic horizontal engagement that takes advantage of the following opportunities:

- Using the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework to support streamlining programs and policies for enhanced impacts on mental wellness, reconciliation and healing, and overall system level change;

- A proposed Gender Based Violence Strategy to govern program approaches; and,

- A Gender Equality CharterFootnote 45 to help support a more strategic and horizontal approach to gender analysis and programming amongst federal public servants.

"We need to get out of the jurisdictional box and figure out a way to work together on this huge issue. I think the Government's strategy to address Gender Based Violence is a great way to get people to think about breaking down silos."

3.3 Learning from other INAC programs

Several events and INAC evaluation reports have been concluded that evaluators find beneficial to the FVPP. These include the Human Rights Tribunal RulingFootnote 46 on Child and Family Services,Footnote 47 which INAC has responded to by sending, for instance, a ministerial representative to lead a wide-ranging engagement and consultation process to reform First Nations Family and Child Services.

In interviews with INAC's social program areas and other departments, the Human Rights Tribunal Ruling is viewed as having the potential to influence program design and funding for a broader cross-section of federal government programs which have, up until now, worked within the specific program's parameters without making the most of the potential synergies among them.

"Child and family (services program) reform might help to catalyze larger-scale changes. There is a rigidity to how (INAC) has worked. You have 20 people sitting in First Nations doing 20 proposals for different funding programs. This is how they become silos in their communities."

The following 2012 INAC evaluation findings may also be considered for horizontal learning:

- Evaluation of On-Reserve Housing (January 24, 2017). The literature review for this evaluation noted: "Many circumstances and factors can lead to a family becoming vulnerable, including poverty, substance abuse, domestic violence, physical and mental illness and a lack of adequat housing."Footnote 48

- Evaluation of the Implementation and Enforcements of Family Homes on Reserve and Matrimonial Real Property Assets (January 24, 2017). Research and preliminary findings indicate that many Indigenous people are not aware of their rights to access the family home after marital breakdown nor are there appropriate supports in the provincial court systems to help them access the legislative tools at their disposal to do so.

- Evaluation of the Urban Aboriginal Strategy (January 24, 2017). This evaluation found a strong need for multi-year funding of initiatives and supports, which was echoed both by shelter directors during FVPP site visits. Further, the need for developing a platform for success stories to benefit community knowledge sharing was identified.

General Observation 1: Investing in evidence-based statistical researchFootnote 49 on family violence occurring inon-reserve communities is essential to better informing and tailoring FVPP approaches. While other federal actors have a role to play in broader data collection at the national level (Statistics Canada, Status of Women), an enhanced FVPP capacity to improve on program data gathering from a paper to an electronic-based system would be beneficial for a more accurate and flexible reporting mechanism.Footnote 50 This will also augment alignment between INAC's programs while strengthening its relationship with other federal departments.

4. Evaluation Findings: Shelter Capacity and Performance (Effectiveness / Success)

This section examines whether shelters are meeting the needs of clients in terms of access and service (Q3); if funding structure(s) are contributing to effective program delivery (Q5); and, overall result impacts of investments (Q6).

A main focus of the FVPP's protection component has been on consolidating the shelter network in on-reserve communities by adding five shelters (from 36 to 41 since the 2012 INAC evaluation) and, as announced in Budget 2016, adding another five facilities for a total of 46. In addition, key accomplishments include: renovations to infrastructure and improvements in safety features, and in an increase in training opportunities for shelter staff.Footnote 51 As a response to the 2012 INAC evaluation recommendations, the program instituted a regular calendar of site visits across the country in order to ascertain issues emerging across its network of shelters and to incorporate these visits as a regular performance measurement technique. The visits resulted in follow-up actions and remedial measures addressing budget management, shelter governance, and infrastructure needs. Furthermore, the FVPP's own 2016 study/survey of shelter directors helped draw a composite picture of shelter requirements, such as training and infrastructure.

Evaluators found that increasingly, the FVPP is expending more thought and effort to collect data (2016 survey, site visit reporting) across the network of shelters to better understand the strengths and weaknesses as a whole, and not simply as individual shelters. However, a major limitation in tracking trends (e.g. shelter usage) is the lack of consistent, electronic data generated by shelters, which translates into limited data for strategic planning purposes by Headquarters and regional offices.

4.1 Shelter Facilities - Programs and Services

Responses from shelter clientsFootnote 52 corroborate positive statements on shelter services and general support from shelter staff. Clients noted that the inherent value of the staff extends well beyond their mandate of providing shelter and protection. Clients mentioned that staff went beyond their assigned duties to accompany their clients beyond the crisis phase.

Recurrent themes that emerged throughout the evaluation included the need for enhanced attention to: transition/second stage housing; outreach and prevention programs for young mothers; programming for men and teenage boys; specialized counselling for children who witness violence; and, awareness of elder abuse. Further, a need for staff training, including staff support and self-care, were identified. The need for additional space to accommodate these programs and/or to support clients with co-occurring diagnoses was often cited as an urgent requirement. The recurrent themes pose a challenge to the 41 INAC-funded shelter networks that largely caters to emergency shelter needs. For instance, 18 of these facilities cater to transition needs by committing beds to, or have a specific transition or second stage mandate. See Table 6, which provides the type of services offered and the number of beds available.

| Type of services offered | Total Shelters (%) | Beds |

|---|---|---|

| Only emergency | 16 (47.1%) | 217 (43.8%) |

| Only second stage and/or transition | 6 (17.6%) | 81 (16.3%) |

| Combined emergency and second stage/transition house | 12 (35.3%) | 197 (39.8%) |

| Total: | 34 Footnote 54 | 495 |

Annual operating budgets for shelters vary between $118,321 (Ross River First Nation, Yukon Territory) to $934,000 (Six Nations, Ontario) for larger facilities. Approximately 20 percent of INAC funded shelters have a regular supplement from provincial authorities for operating expenditure, some full or part-time staff or for specialized program delivery.

Interviews and site visits confirm that FVPP-funded shelters assist women and children fleeing family violence and when space is available, serve as emergency housing for these same women and others from on-reserve communities. However, and depending on the region/province, shelter or in some cases emergency housing can be provided for Indigenous women outside of the reserve from various locations and distances. For example, some women travel several hours to access shelters as there is no shelter in their community. Barriers to access, including transportation, will be treated in the following section (4.1.1).

Based on the evaluation research, the policy of many shelters on- and off-reserve is not to turn away anyone seeking help. The services provided include counseling, referrals, transportation and support, education and life skills, cultural and traditional teachings, and fitness and recreation activities. Others provide programs with the view of helping children who, by virtue of having witnessed abuse, are also considered trauma victims.

There does not appear to be a common approach as to the number and specific type of services provided. However, a trend that surfaced during the evaluation is that large shelters, with transition housing facilities like those at Akwesasne or Six Nations (which are in proximity to larger cities where access to resources and programming are better), tend to have more highly qualified staff and health and wellness techniques than those in remote and isolated areas. As noted, 20 percent of shelters have additional funds from other sources, which allow them to expand their staff as well as the types of programming available.Footnote 55

Small shelters often serve smaller populations in more remote areas and tend to offer a narrow range of services either due to limitations in budget and in staff capacity. However, to offset this, some shelter directors seek creative and cost-effective solutions to direct women in need of other services to off-reserve facilities where these may be available.

4.1.1 Shelter Use and Barriers to Access

Finding 7: Data on shelter use is inconsistent and manually collected across the INAC – funded shelter network. This creates major limitations for programmers in terms of making strategic decisions regarding shelter use and capacity and in responding to calls for increased transitional housing.

Trends in Use

The request for more transition housing was a consistent message communicated to the evaluators in interviews and site visits. While the FVPP funded shelters provide essential emergency services for victims of family violence, shelter clients are left in a vulnerable position once they leave the shelter and need to seek residence elsewhere. For these individuals, the risk of continued abuse remains if the alternative is to continue living with the perpetrators.

Given the demonstrated need for transition housing, it is worth considering whether preexisting emergency shelter facilities can be converted to, or function as second stage housing. In the evaluators' survey, 50 percent of the shelter directors who responded stated that their shelters only attained full use capacity twice a year.Footnote 56 Where shelters were filled to capacity, most directors and staff stated that they would contact the closest shelter to organize an alternate location for victims seeking emergency services. If coordination between service providers could be further enhanced (as discussed in Section 3.1.4), it would mean that some emergency-designated beds could be converted for transition housing purposes, allowing shelters to transfer clients in times of high capacity. These considerations are essential to further improving the design of FVPP shelter services because it recognizes the issue of family violence as a sequential problem.

A major impediment in making decisions of this nature, identified by evaluators and FVPP programmers is INAC's current system of data collection at shelter source. In an attempt to reduce reporting burden on First Nation's communities, efforts have been made to shorten reporting templates, reduce qualitative information fields and limit frequency of reporting to a minimum. Overall, the current system generates inconsistent data across the facilities and a majority of shelters only collect data manually. This process increases the risk of error and miscounting. For example, the current numbers analysed annually by FVPP programmers on use do not refer to multiple visits by the same individual and/or identify the length of stay as important indicators.

Such data shortcomings of INAC-funded shelters impede a full review and analysis of the frequency of use and overall trends until sound quantitative data can be generated consistently and over an extended period. Programmers are considering how best to work with Statistics Canada to collect data from INAC funded shelters as part of a shift to a more strategic approach in program analytics.

Further, FVPP programmers referenced the Ontario's Women In Safe Housing (W.I.S.H.) system as a model that could be used for improved data collection on shelter usage. Through the W.I.S.H., the provincial government has linked all shelters in the province (including INAC-funded facilities) to an online data collection system. Shelter staff are trained in the use of the system and must enter all clients' profiles into the system. Interviewees from site visits have suggested that the system allows different shelters to track clients through their continuum of care with other health and social service providers.

The use of a W.I.S.H.. (or a similar) system by shelters would enhance data gathering for First Nations and strategic planning for the FVPP. This would encourage the initiation of evaluations of the current reporting system among First Nation shelters and help examine whether and how early appropriate data is collected, is available and accessible in the program's records, what improved outcomes for the victims or families are, and promote changes based on sound research. Moreover, where appropriate data are not accessible, service providers who may wish to engage in or collaborate may not be able to provide or obtain the basic information necessary for their needs and purposes. However, with the appropriate data collected and maintained, critical pathways can be explored in areas in which long-term results may not be easily obtained.

Barriers to Accessing Service

Accessing shelter programs and services can be problematic. This is evidenced in the evaluation's site visits, focus group sessions, key informant interviews as well as surveys, which confirmed that while some existing shelters record, to some extent, information on their incoming clients, they also serve other communities, which are located at considerable distances from their locations, including remote and isolated northern ones.

While a range of services is offered by shelters, many shelter staff report that clients cannot access them due to an overall lack of awareness of what help may be available to them. This is compounded by other barriers, including, but not restricted to: limited transportation options; sense of isolation or shame; homelessness; unemployment; addiction to illegal substances; family dysfunction; mental health issues; poverty; lack of on- and off-reserve services (e.g., of child care); and a certain amount of "normalization" of violence in the community, which in the first place diminishes an individual's motivation to seek help. Some shelters allow individuals to stay longer, beyond the accepted two to three week crisis period because of reasons such as the dearth of transition houses or the need for mental health and addiction help.

Transportation

Finding 8: Transportation (and the lack of money) are serious challenges in Indigenous communities, affecting victims' ability to access shelters and pay for childcare while clients not residing within the shelter are receiving support.

INAC officials are aware of the barriers that remote communities face with respect to accessibility and transportation. This was acknowledged in 2011 with the attempts to assess geographic analysis / coverage of the network of shelters (see Section 3.1.4). Because of the geographic location of rural Indigenous communities, transportation is a necessary cost. In Alberta, for example, shelters have had to devise ways to transport family violence victims for short distances (local) as well as from distant points and isolated reserves.

The situation is particularly challenging for shelters located in rural, remote and isolated communities where the possibility of partnerships and referrals are more limited. In communities where most community members do not own vehicles, public transport is often non-existent, and services are hard to reach, shelters need local transportation to ensure that their clients are able to access other communities' agencies to obtain health and other services.Footnote 57 The Mishkeegogamang First Nation in northwestern Ontario is spread out over two main community sites some 25 km apart, creating pressure on the Band Council to address community transportation; however, there appears to be a lack of funds for an imminent solution.Footnote 58 Even if transportation were available, many community members interviewed say that the lack of childcare is also a barrier to attending shelter-sponsored programs.

Quality of facilities

The document reviews suggests that there is some variance in terms of the adequacy of shelter facilities. In the Online Staff Survey, certain respondents cited a number of issues covering: safety and security (i.e. lighting, alarms); lack of children's play areas and ramps for wheelchairs; and maintenance (i.e. roofing, plumbing). However, these issues appear to be more isolated than systemic; the majority of shelter ratings from the aforementioned survey varied from "reasonable" to "good" in terms of the state of the building.

Culturally appropriate services

While many shelters offer to varying degrees culturally appropriate services, there remains a need for staff training on cultural sensitivity as noted in the document review. Furthermore, language is seen as a barrier to clients' access to shelter services.Footnote 59 There are also clients that would benefit from more programs offered in their native language. At an INAC-funded shelter in Saskatchewan, several programs are designed with the collaboration of elders so that native language is incorporated in the training: according to some interviewees, "language is the spirit of culture, if language dies then the cultural values struggle to survive."

Fear of stigma

The document review further brought to light the fear that clients particularly have of coming forward and accessing shelter services due to confidentiality issues. The communities that house shelters or transitional houses are often times small and everyone knows one another. The shelter staff do what they can to keep the clients protected but no matter how many safety features they have, '''people talk'.

General Observation 2: In order to enhance data collection in First Nation communities, it would be beneficial for the FVPP to explore with provincial/territorial counterparts the existing information management systems (health and social services) available in each province or territory.

4.2 Shelter Operations

Finding 9: Shelter staff are limited in their capacity to deliver prevention programming in the community as they are fully engaged in protection activities, including shelter client support.

With respect to shelter operations, the evaluation identified four key challenges faced by shelter staff: shortage of staff; inadequate salary compensation; location of the shelter; and need for training. Each of these areas is discussed briefly below, followed by additional elaboration on training.

- Staff shortages. On evenings and weekends, shelters are typically staffed by just one person, which may limit the shelter's ability to ensure the safety of both clients and staff. This was a key concern noted by shelter staff in both interviews and survey results. Some changes have occurred to improve the physical barriers, infrastructure, and security of the shelters; however, shortage of staff was noted as a key concern. In the evaluation's online staff survey, it was noted that the lack of space for beds and the conditions of the shelter infrastructure itself were key staff concerns. During the site visits most shelter directors and staff stated that there was insufficient money to maintain and do major repairs to the shelters.Footnote 60

- Inadequate salary compensation. The issue of insufficient salary came up a number of times. Shelter employees and people involved in prevention projects are critical resources for success. Their skill, commitment, and capacity are essential to maintain services to Indigenous clients who were victims of family violence. According to interviewees and site visits, without annual salary increases, retaining the services of skilled staff is difficult. Additionally, staff turn-over compromises the ability to deliver consistent service and care.

- Location of the shelter: Related to the preceding is a shelter's location. Knowledge transfer and opportunities to enhance staff capacity (especially in remote communities) tend to suffer due to lower levels of training and lack of experienced shelter staff. As a result of the limited human resource capacity, these shelters tend to offer a narrow range of services. Conversely, the evaluation found that when shelters are in closer proximity to urban areas, the reported trend is that well-trained staff may stay but often, not for long in INAC-funded shelters as they may find a higher paying job in a provincial shelter or other facility.