Evaluation of Recruitment, Development and Retention Activities at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

Final Report

January 2016

Project Number: 1570-7/14096

PDF Version (832 Kb, 99 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Context

- 4. Findings – Recruitment

- 5. Evaluation Findings – Development

- 6. Evaluation Findings - Retention

- 7. Conclusion and Points for Consideration

- Appendix A: Key Informant Interview Methodology

- Appendix B: Data Analysis of Public Service Employee Survey Methodology

- Appendix C: Average Number of Days to Staff Positions

- Appendix D: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Human Resources Risk Analysis

List of Acronyms

| DRAP |

Deficit Reduction Action Plan |

|---|---|

| EPMRB |

Evaluations, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| EPMRC |

Evaluations, Performance Measurement and Review Committee |

| HRWSB |

Human Resources Workplace Services Branch |

| HR |

Human Resources |

| INAC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

| MAF |

Management Accountability Framework |

| PSES |

Public Service Employment Survey |

| PSPM |

Public Service Performance Management Agreements |

| SCARF |

Staffing and Classification Action Request Form |

Executive Summary

Overview and Scope

From 2010-11 to 2014-15, four of INAC's Annual Corporate Risk Profiles assessed Indigenous and Northern Affairs' (INAC) ability to recruit, develop and retain sufficiently qualified, experienced and representative human resources in a timely manner as high risk. As a result, INAC identified in its 2014-15 departmental approved Five Year Evaluation and Performance Measurement Plan an evaluation of recruitment, development and retention activities. The evaluation was carried out in 2015-16 and covered the period April 2010-11 to 2014-15. It was carried out as an internal services evaluation.

Fundamentally, recruitment refers to the activities involved in recruiting human resources, including planning for and attracting applicants, assessing, selecting and deploying candidates, and integrating new employees. Development refers to activities and transactions that facilitate employee development, including planning, and designing and delivering professional development. Retention refers to activities and transactions for retaining human resources, such as the provision of terms and conditions, benefits, employee assistance, and workplace health and safety. Each of these areas was examined as part of the evaluation.

Methodology and Lines of Evidence

The study was designed as a 'multi-method descriptive evaluation'. It was conducted by documenting processes, outputs and outcomes. Information was gathered using document review, interviews, discussion groups, regional site visits, administrative data, a comparative analysis of INAC's Public Service Employment Survey (PSES) results, and a review of corporate risk profiles.

Findings and Points for Consideration

The evaluation identified fifteen key findings and a dozen points for consideration meant to help improve the efficiency and effectiveness of recruitment, development and retention activities. Formal recommendations were not identified given that the evaluation reflects a review of internal services processes. As responsibilities for recruitment, development and retention are shared by management across INAC, the main themes and considerations outlined what might emerge as a departmental action plan to address key areas for improvement.

Findings – Recruitment

Workforce Decline – INAC's workforce population experienced a decline comparable to other departments, with increased vacancies particularly in northern regions. In terms of composition, the proportion of middle-aged employees at INAC has increased, while the proportion of younger employees has decreased. This is consistent with the average workforce of the public service.

Given the above, the evaluation suggests that the Department consider closely monitoring and assessing vacancy levels in the North in order to manage the risk that high vacancies in these regions negatively impact northern staff and programming.

Indigenous Recruitment – While the Department has not yet achieved 50 percent representation by Indigenous peoples, their level of representation is significantly higher than the general workforce market availability for this population, and INAC has made progress on its objective. However, in the absence of a positive change in Indigenous hiring trends, development and retention, under the assumption that INAC's workforce stabilizes, the Department may not experience an increase in Indigenous workforce representation as per departmental targets.

The evaluation observes that the aspirational 50 percent target is a long-term objective hence no timeframe for achievement of this objective was set; this makes meaningful measurement of the Department's progress challenging as it continues to advance in making every effort to ensure that Aboriginal people are equitably represented across all occupational groups and levels in the Department, including management positions. Expanding current Indigenous recruitment initiatives, such as an outreach program for Indigenous students and workers focused on opportunities to work at INAC and the federal government as a whole will contribute to the aspirational objective of 50 percent representation.

Human Resources Service Delivery and Hiring Processes – Human Resources (HR) service delivery at INAC underwent major restructuring during the time period examined by the evaluation, particularly with regards to activities and processes related to recruitment and related activities. The evaluation found that the roles and responsibilities of employees and hiring managers under the Common Human Resources Business Process implemented at INAC as of 2014 remain unclear, and hiring managers find staffing processes to be lengthy and cumbersome with excessive oversight. In addition, the creation of Service Centres has resulted in challenges to timely service delivery in regions, including confusion over roles and responsibilities for all parties involved in the staffing process, and unintended gaps in expertise.

Given the above, the evaluation suggests:

- Providing staff and INAC managers involved in hiring with additional training and support to enhance understanding of and compliance with the Common Human Resource Business Process;

- Improving service delivery by Service Centres to regional offices by creating new methods of triaging service requests from regional offices to Service Centres, or realigning the distribution of request by volume rather than by region; and

- Re-evaluating staffing oversight bodies as recommended in the 2013 Audit of Management Services.

Development

Employee Training Opportunities – The Department has increasingly relied on lower cost online training for their employees to access career-related training. While INAC's employees tend to have higher levels of satisfaction with training than comparable departments, there are opportunities for improvement.

The evaluation suggests strengthening development activities through improved monitoring of planned versus actual training as identified in employee Public Service Performance Management agreements (PSPM) and learning plans, and tracking development and training requests of staff and managers to help both INAC and the Canada School of Public Service tailor its course offerings employee needs.

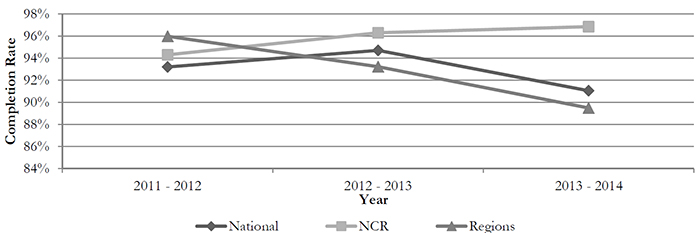

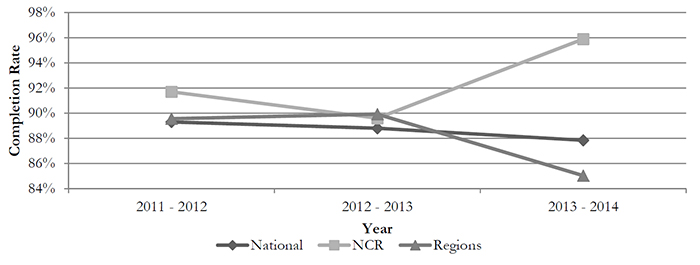

Use of Performance Management Tools – While completion of performance management agreements and learning plans have consistently met target levels, regional use of PSPM agreements tends to be lower than rates observed in the National Capital Region.

Given the above, INAC may wish to consider completing a trend analyses based on the content of employee learning plans by province/territory to promote consistent and effective employee development planning across the Department.

Retention

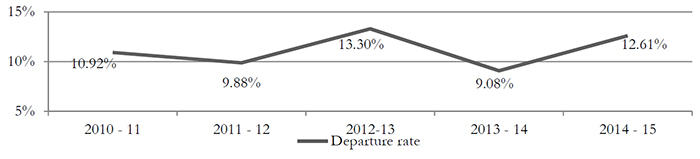

Departure Rate – While the departure rate remained relatively stable between 2010-11 and 2014-15, it has consistently exceeded the entry rate. This gap coupled with an increase in the departure rate from approximately nine percent in 2013–14 to just under 13 percent in 2014–15 may indicate a need for improved activities aimed at retaining an experienced, qualified and representative workforce.

Employee Wellness – INAC has taken concrete steps to improve workplace wellness for its employees. In addition, INAC's Human Resources and Workplace Services Branch is working to address the discrepancy between incidents of harassment and conflicts reported to the Centre for Integrity, Values and Conflict Resolution and self-declared harassment in the anonymous Public Service Employment Survey.

Given the above, the Department may wish to consider:

- Promoting vacation use rather than 'banked' vacation through effective communication to help employees maintaining work-life balance, and monitor sick leave utilization and vacation utilization as proxies for wellness across the Department.

- Ensuring managers are proficiently informed and communicate regularly and effectively with staff about actions that may constitute harassment, the impacts of disrespectful behaviour in the workplace, and options for employees seeking conflict resolution.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch (EPMRB) at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) undertook an evaluation of recruitment, development and retention activities within the Department. The decision to conduct this evaluation was supported by evidence gathered as part of INAC's Corporate Risk Profile from fiscal year 2010-11 to 2014-15. For four of these five years, the Corporate Risk Profile assessed the Department's ability to recruit, develop and retain sufficiently qualified, experienced and representative human resources in a timely manner as a high risk.Footnote 1

INAC's corporate Human Resources Capacity Risk area within the Corporate Risk Profile speaks to the fundamental need to accomplish INAC's organizational goals through its people. INAC must succeed in attracting, recruiting and retaining sufficiently qualified, experienced and representative employees in a timely manner in order to support achievement of its strategic outcomes.

This evaluation aimed to examine the efficiency and effectiveness of the structures and processes within INAC that support recruitment, development and retention activities, as well as the Department's performance in each of these areas. Findings and the points for consideration contained in this evaluation provide an understanding of the factors that contribute to INAC's high Human Resources (HR) risk environment, support the development of risk mitigation strategies, and are designed to help improve the design and delivery of future activities associated with recruitment, development and retention.

1.2 Organization of the Report

The report is organized into seven sections. The remainder of this section briefly profiles the Department's vision for recruitment, development and retention activities and describes the roles and responsibilities of both sub-delegated managers and Human Resources and Workplace Services Branch (HRWSB). Section 2.0 – Methodology outlines how the evaluation was conducted, including limitations and mitigating strategies. In order to help set the stage for the evaluation, Section 3.0 – Context, provides an overview of the policy landscape in which recruitment, development and retention activities occur in the federal public sector and how these influenced INAC's recent approach to service delivery. Findings related to each of the major themes of the evaluation are presented in Section 4.0 – Findings: Recruitment, Section 5.0 – Findings: Development, and Section 6.0 – Findings: Retention. Conclusions are presented in Section 7.0, as well as points for consideration by INAC management.

Findings and points for consideration are interspersed throughout the text, to provide senior management with key points for consideration. The intention is that some of these points may lead to changes that enhance the performance of the Department's recruitment, development and retention activities, to further contribute to the achievement of departmental objectives.

1.3 Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Mandate

INAC is one of 34 federal departments responsible for meeting the Government of Canada's obligations and commitments to First Nations, Inuit and Métis, and for fulfilling the federal government's constitutional responsibilities in the North. INAC's mandate is to support Indigenous people (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) and Northerners in their efforts to:

- Improve social well-being and economic prosperity;

- Develop healthier, more sustainable communities; and

- Participate more fully in Canada's political, social and economic development — to the benefit of all Canadians.Footnote 2

1.4 Vision for Recruitment, Development and Retention at INAC

The Department's vision for recruitment, development and retention activities is outlined in its Corporate Human Resources Business Plan for 2014 – 2020. The Plan outlines a vision for people management of "Ensuring that the right person is in the right job, at the right time, to support leadership at all levels, efficiency, productivity, excellence and engagement." Within this plan, four priorities are identified:

- Enhance performance, productivity and talent management;

- Create a culture of continuous learning;

- Provide a healthy and respectful workplace; and

- Innovate and make use of modern human resources tools.

Within INAC, the primary responsibility for recruitment, development and retention activities rests with managers who have been given the sub-delegated authority for staffing and -related actions.Footnote 3 Additionally, the Department's Human Resources and Workplace Services Branch hereafter referred to as HRWSB or 'The Branch', plays a major role in supporting these activities.

The remainder of Section 1.0 briefly describes the roles and responsibilities of sub-delegated managers, HRWSB, its structure and resources, and its roles and responsibilities, as they pertain to recruitment, development and retention.

1.5 Roles and Responsibilities for Recruitment, Development and Retention at INAC

The primary accountability for recruiting, developing and retaining staff rests with all members of a department's management team to whom the Deputy Minister has granted the relevant authorities. INAC has a Sub-Delegation Instrument for Human Resources, which lays out the levels of responsibilities according to managerial level. The Instrument is developed and updated by the HRWSB, and approved by the Deputy Minister. The role of non- managers is important to consider when assessing overall strengths and weaknesses of INAC's performance in its recruitment, retention and development activities.

For its part, INAC's human resources function, the HRWSB, provides strategic information and advice to INAC managers with respect to all -related activities. The HRWSB is headed by a director general who reports directly to the Deputy Minister. The Branch has six directorates, five of which undertake activities directly linked to recruitment, development and retention. These include:

- Human Resources Planning, Executive Group Services and Performance Management;

- Human Resources Policies;

- Human Resources Services Delivery and Data Integrity;

- Learning and Well-being; and

- Integrity, Values, Ethics and Conflict Resolution.Footnote 4

The sixth directorate, Security, Occupational Health and Safety, and Accommodation, is not discussed in the report given that its activities do not have a strong linkage to recruitment, development and retention activities.

1.6 Human Resources and Workplace Services Branch Structure and Service Delivery

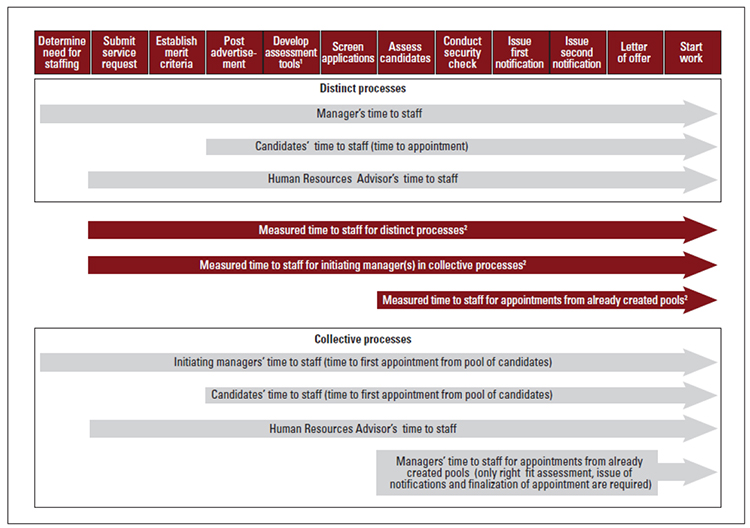

Between 2011-12 and 2013-14, human resources service delivery changed significantly throughout the public service when all departments implemented the Treasury Board's Common Human Resources Business Process. Implementation of the Common Human Resources Business Process was completed across Government in March 2014.Footnote 5 Treasury Board Secretariat's objective in implementing the Common Human Resources Business Process was to increase the efficiency of human resources management government-wide by delineating a more streamlined human resources management business process. The Common Human Resources Business Process detailed the roles and responsibilities for all employees involved in -related activities. Non- managers assumed increased responsibilities in the process, and personnel assumed an increased monitoring function within federal departmentsFootnote 6

The function in federal departments performs activities related to recruitment and staffing under the constraints of a multitude of laws, directives and regulations. With respect to staffing, Advisors are responsible for ensuring that managers' staffing actions conform to current regulations; and HRWSB and the Human Resources Operations Committee (described below) monitors and approve high risk actions. Additionally, HRWSB safeguards the Deputy Minister's delegated authority for human resources, which was conferred via the Public Service Employment Act, and is sub-delegated to INAC managers via the Departments' Sub-Delegation Instrument (2014) for human resources. This document is developed and updated by the HRWSB and signed by the Deputy Minister. Of note, the Common Human Resources Business Process, implemented between 2013 and 2014, increased the supervisory role of HRWSB over the staffing process at INAC.Footnote 7

The Department also reengineered its delivery model between 2012 and 2014, in response in part to the Deficit Reduction Action Plan (DRAP), and to align human resources service delivery with the Common Human Resources Business Process.Footnote 8 A general illustration of the transition can be found in figures 1 and 2.Footnote 9

The above factors resulted in several significant changes, including:

- The establishment of a Workforce Management Board (later renamed the Human Resources Operations Committee), created at INAC's National Headquarters in the National Capital Region to ensure that public servants affected by DRAP were prioritized for appointments within the Department, and to approve sectoral plans and higher risk staffing/classification actions.

- The development of a central National Administrative Unit at National Headquarters in order to relieve advisors time by processing administrative staffing and classification actions for them, leaving advisors to focus on processing non-administrative actionsFootnote 10.

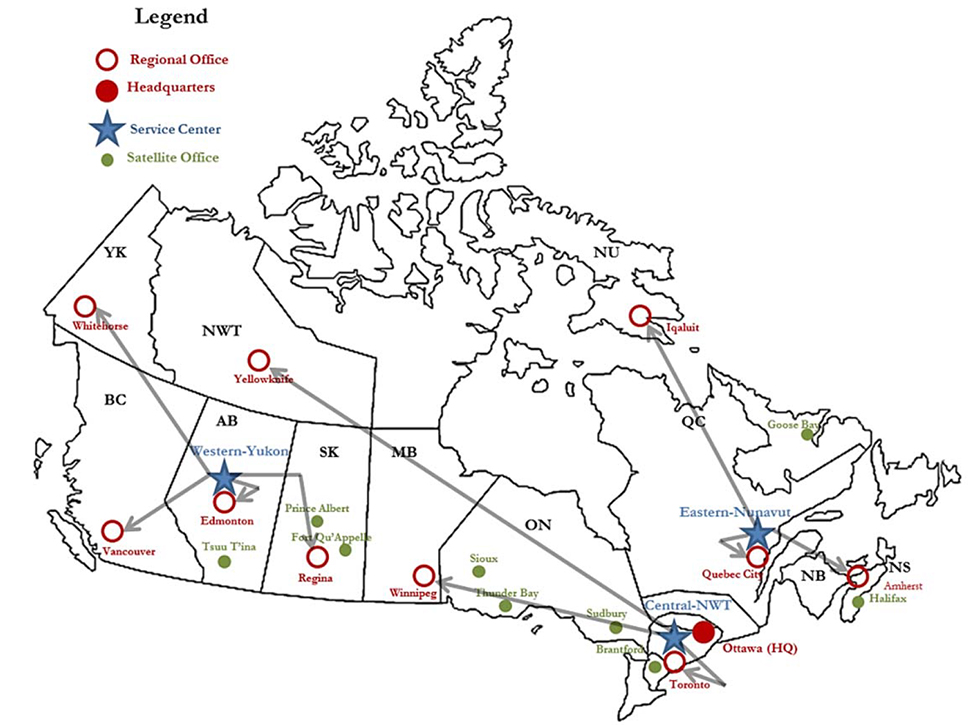

- The relocation of functions and staff located within each of INAC's ten regional offices to three Service Centres located in Alberta, Quebec and Ontario. The Centres became operational in September 2013. Regional offices retained two positions (a Human Resources Manager and a Human Resources Specialist), often referred to as 'footprints'. The intent was to have these positions remain to support labour relations and planning functions in the regions.

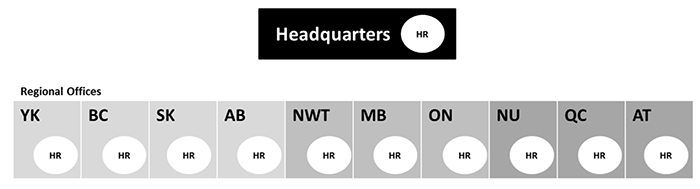

Figure 1: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Human Resources Function (Pre Reengineered, circa 2012-13)

Text alternative for Figure 1: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Human Resources Function (Pre Reengineered, circa 2012-13)

This diagram describes the structure for provision of Human Resource services at the Department of Indigenous Northern Affairs Canada. At the top of the diagram, a box for "Headquarters" indicates there is an HR branch in the department’s central headquarters location. Below this 10 separate boxes below this indicate human resource branches in each regional office in Yukon, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Northwest Territories, Manitoba, Ontario, Nunavut, Quebec, and the Atlantic region.

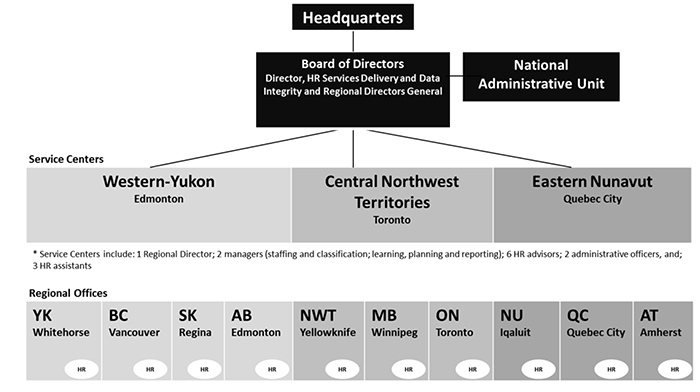

Figure 2: Human Resources Function (Reengineered, 2013-14)

*Regional Offices contain Regional Footprints who handle labor relations and planning

Text alternative for Figure 2: Human Resources Function (Reengineered, 2013-14)

This diagram describes the structure of the Human Resources Function at INAC following the implementation of streamlining initiatives in 2013-14. The diagram is oriented top to bottom, showing the relationship between headquarters and the ten regional offices. At the top of the diagram, "headquarters" flows to the "Board of Directors" including the Director, HR Services Delivery and Data Integrity and Regional Directors General. To the right, the board of directors flows to the "National Administrative Unit."

The board of directors flows downward to the three Service Centres. Each Service centre employs one regional director, two managers (staffing and classification; learning, planning and reporting); six HR advisors, 2 administrative officers, and 3 HR assistants. Each Service Centre liaises with 3-4 regional offices, each of which contains a "Regional Footprint" responsible for labour relations and planning.

The "Western Yukon" service centre in Edmonton is responsible for the regional offices in Whitehorse, YK; Vancouver, BC; Regina, SK; and Edmonton, AB. The "Central Northwest Territories" service centre in Toronto is responsible for the regional offices in Yellowknife, NWT; Winnipeg, MB; and Toronto, ON. The "Eastern - Nunavut" service centre is responsible for regional offices in Iqaluit, NU; Quebec City, QC; and Amherst, NS for the Atlantic Provinces.

In addition, all federal departments had to adjust to the loss of their pay administration services through the consolidation of the pay function within the Public Service Pay Centre at Miramichi, New Brunswick.

The three newly created Service Centres were established in Alberta, Quebec and Ontario. Each Centre was given the responsibility of serving between two and three of INAC's 10 regional offices, including one northern regional office, as follows:

- Western-Yukon Service Centre, located in Edmonton, Alberta - Serves the Yukon, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Alberta;

- Central-Northwest Territories Service Centre located in Toronto, Ontario - Serves regional offices in the Northwest Territories, Manitoba and Ontario; and

- Eastern-Nunavut Service Centre, located in Quebec City - Quebec and serves regional offices in Nunavut, Quebec and the Atlantic region.

The Service Centres were tasked with providing non-administrative -related services to the regions, such as advice, and also of participating in some parts of the processes involved in collective staffing actions, reclassifications, and the creation of new positions.

In terms of Governance, Service Centres are led by regional directors. They report to the Director of Services Delivery and Data Integrity, who reports to the Director General of HRWSB. The Service Centres are managed by a board of directors that includes the Director General of HRWSB and the regional directors general.Footnote 11

1.7 Recruitment, Development and Retention Stakeholders

Recruitment, development and retention activities are implemented or influenced by a number of stakeholders, both internal and external to the Department. Internal stakeholders include: executives; managers; individual employees; the Chief Financial Officer; Communications; and Legal Services.Footnote 12

Externally, HRWSB maintains partnerships with federal government stakeholders to support the fulfillment of its duties. The Treasury Board Secretariat, the Public Service Commission, and the Canada School of Public Service are all external stakeholders that contribute policies, programs and development activities that influence the implementation of recruitment, retention and development within the public service.

1.8 Governance of Recruitment, Development and Retention Activities

Over the time frame covered by the evaluation, INAC has had in place several committees that play various roles with respect to recruitment/staffing, development and retention activities. Key ones of relevance to the evaluation and referred to later under evaluation findings include:

- The Human Resources Workplace Services and Management Committee – Human Resources Workplace Services and Management Committeeassists senior management in fulfilling its obligations related to overall human resources management. This includes executive resourcing and workforce and workplace related matters.

- Human Resources Oversight Committee (formerly the Workforce Management Board) – Human Resources Operations Committee operates as a senior management forum to ensure that workforce management mechanisms and planning for non-EX positions and personnel are aligned with departmental priorities and remain consistent with the Human Resources Management Framework.Footnote 13

- National and regional workforce adjustment committees – Workforce Adjustment Committees exist at regional and national levels in order to share information and suggest recommendations for the effective application of the Workforce Adjustment Directive.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Objective and Scope

The objective of the evaluation was to determine the extent to which there are appropriate systems and processes in place to facilitate the recruitment, development and retention of staff in support of the achievement of HRWSB's vision, and the work completed by the Department. Recruitment, development and retention activities are fundamental components of the standard business process model for the human resources management function, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Human Resource Management function – Management Business Process (Sub-functions)Footnote 14

Text alternative for Figure 3: Human Resource Management function – Management Business Process (Sub-functions)

This diagram describes the management business process sub-functions in the Human Resource Management function. A circular arrow shows a cyclical relationship between five phases:

- Recruit: Attracting, assessing, selecting, staffing and integrating human resources.

- Develop: Developing the knowledge and capabilities of human resources.

- Retain: Providing the terms and conditions of employment, ensuring a safe and healthy workplace, and managing the separation of employees.

- Measure (performance): Evaluating the effectiveness of human resource functions.

- Plan: Determining how human resources will be used to achieve goals and objectives.

Based on the accountabilities outlined in the Common Human Resources Business Process, as well as other models used in the public service to describe the business activities associated with recruitment, development and retention, each of these can be defined to include the following set of activities:

- Recruitment – Refers to the activities or transactions that relate to or affect, in a specific manner, the recruitment of human resources, including the selection and deployment of new employees.Footnote 15 These activities are described sequentially in the Common Human Resources Business Process under the category 'Staffing and Employee Integration'. They include: the process of planning a recruitment approach; attracting applicants; assessing applicants and candidates; selecting candidates; and documenting and integrating new employees.Footnote 16 As a result, this evaluation covers the theme of staffing processes within the theme of recruitment.

- Development – Refers to activities and transactions that relate to or affect, in a specific manner, the development of human resources. This may include planning, designing and delivering professional development for employees within an organization.Footnote 17 Development may also include those activities described in the Common Human Resources Business Process under the category 'Employee Performance, Learning, Development, and Recognition', including: the process of addressing organizational learning requirements; developing performance agreements; managing employee performance; managing employee learning and development; and managing employee recognition.Footnote 18

- Retention – Refers to activities and transactions that relate to or affect, in a specific manner, retaining human resources such as the provision of the terms and conditions of employment, including: payment, benefits and employee assistance programs; creating a safe and healthy workplace; administering collective agreements among various groups; and releasing employees from employment at an institution or the public service in general.Footnote 19 These activities are described in the Common Human Resources Business Process under the category 'Workplace Management' and include the process of managing grievances, complaints and discipline, and managing scheduling and modified work arrangements.Footnote 20

In terms of the period of activity examined, the evaluation covers the five fiscal year period from April 2010 to March 2015. At a minimum, five years provides a sufficient timeline to examine changes to recruitment, development and retention within INAC, influenced notably by external and internal factors that have been established to drive a reduction in federal resource utilization.

The evaluation therefore focuses on:

- The external and internal factors that lead to a high-risk rating for Human Resources Capacity at INAC;

- The key structures and processes established and monitored by the Branch, which support recruitment, development and retention within the Department; and

- The performance of these structures and processes, and any positive or negative impacts that they have had on recruitment, development and retention.

2.1.1 Scope Exclusions

Given that responsibilities for recruitment, development and retention activities are shared between management, HRWSB and other key stakeholders, the evaluation does not assess the performance of professional, administrative and technical human resources in the organization.

Also, given the initial Terms of Reference for the evaluation, and the need to manage the scope and level of effort of the study, executive level recruitment, development and retention was not a focus of the work. While highly important to achieving organizational objectives, the executive cadre (representing just under four percent of INAC's workforce) participate in recruitment and development activities that are distinct from those used by the majority of employees at the Department.Footnote 21 Instead, the evaluation focused primarily on these activities as they relate to the four major occupational groups at INAC, namely the PM, AS, EC and CR groups.

2.1.2 Design

The evaluation was conducted as an internal services evaluation at INAC. While it appears on the departmental approved Five Year Evaluation and Performance Measurement Plan, as per Treasury Board Secretariat's Guide to Developing a Departmental Evaluation Plan, internal services are part of the total cost of delivering a program. This gives INAC the flexibility to conduct the evaluation according to issues that are most relevant to evaluation stakeholders. Evaluation issues outlined further in this section reflect primarily the interests of the Department, its management, and stakeholders. However, the evaluation does aim to take into consideration the principles of the Policy on Evaluation with a focus on the relevance and performance recruitment, development and retention activities.

The design used for this evaluation can best be described as a 'multi-method descriptive evaluation', wherein the information gathered is examined to determine the degree to which recruitment, development and retention activities are effective and supporting INAC in achieving its objectives. This was achieved by documenting processes, outputs and outcomes.Footnote 22

2.2 Evaluation Management and Quality Assurance

The Terms of Reference for the Evaluation was approved by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on November 28, 2014. Fieldwork and analysis was undertaken from November 2014 to November 2015. The final draft report was presented to INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on January 25, 2016.

2.3 Lines of Evidence

The following lines of evidence were used to collect data and undertake evaluative work.

Document Review – Over 150 documents were reviewed in support of the evaluation. Internal and external documents were selected based on their relevance to the evaluation research questions pertaining to the themes of recruitment, development and retention at INAC and across the federal government. Documents were categorized as follows: reports (31 percent); planning documents (20 percent); websites (17 percent); guidance documents (seven percent); data tables (three percent); and minutes and presentations (two percent).

Departmental Risk Assessments – Risk assessments conducted between fiscal year 2010-11 and 2014-15 at the program, regional and corporate level were reviewed to provide insight into the human resources risks affecting departmental operations at each level. A sector-based risk assessment for the Northern Affairs Organization was included in the review to account for the challenges and risks specific to meeting the needs of remote northern clients and funding recipients. The complete analysis can be found in Annex A.

Data Review – Internal INAC performance data that detail recruitment, development and retention activities within the Department were reviewed. Data sources included quarterly reports on corporate indicators, HRWSB dashboard reports, and historical data extracted from internal data management systems. Also examined were open-source data for the public service as a whole, available through Treasury Board Secretariat, Statistics Canada and the Public Service Commission. This data was examined in order to compare INAC's performance to other medium-sized federal departments.

Key Informant Interviews and Group Interviews – Interviews and group interviews were conducted with both staff and non- managers. In the conduct of evaluative work, the evaluation distinguished between staff (i.e., employees whose substantive positions are to provide internal services) and non- managers (i.e., managers who engage in -related activities).

Non- managers included regional directors general, directors, managers, and Business Management Units heads. key informants included advisors and assistants located at National Headquarters and in regional offices, as well as the three Service Centres, and employees within HRWSB. Approximately one third (50) of the internal key informant interview and management group interview participants were HRWSB staff, and two thirds of all interviewees (97) were non- directors, managers, advisors and Business Management Unit heads.

Efforts were made to engage other government departments in the evaluation in order to gain an external perspective of recruitment, development and retention activities across the federal government and identify potential lessons learned and best practices. Due to lack of resources and availability of invited parties, only the Public Service Commission was able to participate as an external stakeholder. Four key informants from Public Service Commission participated in interviews.

For a detailed overview of qualitative data collection conducted in support of the evaluation, refer to Appendix A: Key Informant Interview Methodology.

The majority of interviews were completed in person, with some feedback being received via email. Several group interviews were conducted via teleconference and telephone. Feedback was coded using NVIVO, a qualitative software analysis tool used to identify qualitative research trends based on interviewee and group interview findings.

Public Service Employee Survey Analysis – EPMRB commissioned Statistics Canada's Social Analysis and Modeling Division to produce comparative analysis of INAC's Public Service Employment Survey (PSES) results from surveys conducted in 2008, 2011 and 2014.

Statistics Canada compared INAC's results to a sample of five departments of similar size, mandate and composition in order to obtain a sense of performance in the areas under evaluation among a comparator group. Existing PSES analysis compared aggregate departmental results by question and theme; to support this evaluation, a more detailed analysis comparing the differing results of employees within the Department based on identity characteristics, employee tenure, geographic location, and other variables was completed. This commissioned work allowed for more in-depth comparison of INAC performance than what was available in open-source data on the Treasury Board Secretariat website. Additional information on this analysis can be found in Appendix B: Data Analysis of Public Service Employee Survey Methodology.

Site Visits – Service Centres were visited between March and June 2015. Concurrent with each site visit, key informant interviews were held with the Regional Director of Services and group interviews were held with advisors and assistants. In total, 23 informants participated in the facilitated sessions. Relevant documents were also collected during site visits and were included in the document review.

2.4 Strength and Limitations

The following strengths and limitations relevant to the evaluation are worth noting.

2.4.1 Strengths

Contextualization and Clarification of Roles and Responsibilities – The evaluation examined both non- manager activities and HRWSB's activities and provision of services related to recruitment, development and retention. It also considered the context within which these activities were being undertaken over the period covered by the evaluation given changes at a whole-of government level, and within INAC. This contextualization provides an important counterweight to the qualitative results arising from key informant interviews and group discussions, which revealed an often strained relationship between non- managers and staff within the Department. Understanding the context within which recruitment, development and retention activities were carried out allowed evaluators to better interpret findings and provide appropriate considerations to support continued improvement of these activities by the Department.

Balanced Feedback – Evaluators ensured that both and non- staff were represented in interviews and group discussions. Feedback was also elicited from all INAC sectors, including Service Centres and regional offices. Human Resources managers and advisors could speak to human resource service standards, the policy and legislative framework under which services are delivered, and the challenges of supporting hiring managers in their staffing and planning processes. Non- managers, directors, and directors general were able to speak to processes that they are directly involved in on a daily basis. They were also able to speak to the challenges that they face with respect to recruiting the right people in a timely manner and developing and retaining their staff.

2.4.2 Limitations

Comparative Data – The confidential nature of activities makes obtaining comparative data on common recruitment, development and retention metrics, and associated functional costs and outcomes, challenging. Little comparative information on the performance as an Internal Service within and among federal government departments was available to support comparative analysis.

In order to mitigate this challenge, open source data was analyzed, including data available from Treasury Board Secretariat, the Public Service Commission and Statistics Canada. The comparative analysis of INAC's PSES results over the most recent three surveys, performed by Statistics Canada, was also used to assess INAC's performance related to recruitment, development and retention with other similar government departments.

Data Sources – The breadth of data and variability with which data can be analyzed (e.g., inclusion and exclusion of types of employees, etc.), means that determining which data to use for analysis can be challenging. Data available from internal and external sources was sometimes inconsistent and it was not always feasible to report on data from a single source over the full five years. To mitigate this, efforts were made to extract data primarily from internal service reporting tools, and to triangulate this information with secondary sources where possible.

Performance Measurement – While HRWSB does not have a performance measurement strategy similar to those used by programs to track progress, evaluators obtained performance measurement data from the Branch's quarterly corporate indicator reports, and examined documents, including the Plan, dashboards, INAC's Corporate Human Resources Plan (2014 – 2020) and departmental risk analyses.

Level of Availability of INAC Staff and Associated Information – The downward trend in the size of INAC's workforce, which has been affected by a number of cost-saving initiatives since 2012, and the demands to deliver programming and internal services with fewer resources, meant that the evaluation experienced difficulty securing time and information from evaluation participants. The timelines and workload with which the HRWSB at National Headquarters operates, delayed the evaluation team's receipt of evaluation-related material and data, and affected project timelines. The participation of HRWSB staff in group discussions and interviews, while extensive, required frequent rescheduling due to last minute unavailability by staff. This resulted in a more limited timeframe with which to assess data and information, and probe on or explore issues. To mitigate the constraints caused by limited availability, responses from interviews and group discussions were solicited in a variety of means, including e-mail, teleconference, and telephone.

Balance of Reporting – While evaluations can start out with a particular focus, the experiences and issues identified by stakeholders throughout the study process can result in a redefinition of issues or the exploration of other impacts. Given the changes occurring in the Department over the period examined by the evaluation, much of the qualitative feedback provided, regardless of area of enquiry, focused on issues such as hiring and staffing processes. While the focus of the evaluation was and remains recruitment, development and retention, there is a heavier emphasis on recruitment related themes (i.e., attracting, assessing, selecting, staffing and integrating human resources) given the results of fieldwork.

3. Context

The following section provides an overview of the legislative and policy landscape affecting human resources activities in the federal public service over the period covered by the evaluation, as well as the bodies that provide guidance and oversight to the administration of human resources activities in departments.

3.1 Human Resources Management in the Federal Government

3.1.1 Legislative and Policy Framework

Numerous acts, legislation, and various government-wide initiatives have influenced human resources activities across the federal public service over the recent past. Key legislation that sets the groundwork for recruitment, development and retention activities in the public service in Canada include the Financial Administration Act, the Public Service Employment Act, and the Public Service Labour Relations Act.Footnote 23

With respect to initiatives and frameworks, a few key ones are discussed here in order to provide context for the reader and reference when considering the findings of the evaluation.

Public Service Modernization – The Public Service Modernization, introduced in 2003, represented a significant reform of federal human resources management within the last four decades. Its objectives were to create a more flexible staffing framework to manage and support employees and to attract the best people, to foster more collaborative labour-management relations, and to clarify accountability for deputy heads and managers. The Public Service Modernization was crucial as it moved responsibilities and accountabilities for staffing from the Public Service Commission to deputy ministers. Most importantly, under this transition, deputy ministers were given the authority by the Public Service Commission to allocate a range of -related responsibilities by sub-delegating authorities to the lowest management level within departments. Departments were encouraged to pay as much attention to planning to meet their staffing needs as they did to their business cases and budgets. Ultimately, the Public Service Modernization was intended to streamline human resource management in the public service.

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer – The desire by Government to streamline management and internal services gave rise to the creation of the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer in March of 2009. It centralized all human resource activities into a single new agency within the Treasury Board Secretariat.Footnote 24 The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer's mandate is to represent the Government of Canada on all issues relating to human resources, pensions and benefits, labour relations, and compensation. It does so by developing broad policy direction and standards to enable deputy ministers to fulfill their responsibility for people management in their organizations. The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer is also involved in monitoring and reporting on people management, providing guidance on performance management, and improving policies and processes.

Deficit Reduction Action Plan – DRAP was first introduced in the Federal Budget of 2011 as a strategy to contain resource activities into single ongoing savings by 2014-15.Footnote 25 In implementing cost containment and efficiency improvement strategies, DRAP ultimately influenced activities in terms of spending and hiring processes.Footnote 26 The overall impact of DRAP on INAC is discussed further in the report.

Canada School of Public Service – The Canada School of Public Service offers opportunities for managers across the federal government to develop skills needed to be effective leaders and for employees to develop skills needed to excel at their jobs. It aims to provide foundational development aimed at laying the groundwork for a common set of skills and values within the public service.

Public Service Commission – The Public Service Commission safeguards merit-based hiring, non-partisanship, representativeness (Indigenous people, visible minorities, women, and people with disabilities) and the use of both official languages in the public service. The Public Service Commission delegates to deputy ministers the appointment related authorities they require to execute their management responsibilities and human resources plan.

Blueprint 2020 – Blueprint 2020, released in June of 2013, defined a vision for Canada as having a world-class public service equipped to serve Canada and Canadians. In order to achieve this, four guiding principles were established including: an open and networked environment that engages citizens and partners for the public good; a whole of government approach that enhances service delivery and value for money; a modern workplace that makes smart use of new technologies to improve networking, access to data and customer service; and, a capable, confident and high-performing workforce that embraces new ways of working and mobilizing the diversity of talent to serve the country's evolving needs.Footnote 27

The next phase of Blueprint 2020, Destination 2020, was released by the Clerk of the Privy Council and Head of the Public Service in May of 2014. Within the report, the theme of People Management involves an improved approach to staffing, focused on results, simplified job descriptions, enhanced tools and capacity for learning official languages, and a government-wide commitment to learning.Footnote 28

The remainder of the report outlines the key findings from the evaluation as they relate to the themes of recruitment, development and retention. Where feasible, data and information has been included in areas of greatest relevance, recognizing that all three areas can be interconnected, as each represent a key component of the standard human resources business process model (refer to the model shown in Figure 3 earlier in the report).

4. Findings – Recruitment

As noted in Section 2.1, recruitment includes numerous activities such as: the process of planning a recruitment approach; attracting applicants; assessing applicants and candidates; selecting candidates, and documenting and integrating new employees. As a result, this evaluation covers a variety of themes within the theme of recruitment.

The following key evaluation questions with respect to recruitment and its related activities are addressed in this section:

- What is the state of INAC's workforce landscape?

- What are the Department's recruitment activities and are they effective?

- Will INAC's Indigenous recruitment strategy and activities enable the Department to fulfill its commitment to attain 50 percent representation by Indigenous peoples?

- Are processes to staff qualified recruitment candidates efficient?

- What impacts have external and change drivers (i.e., DRAP and the implementation Common Human Resources Business Process) and internal reengineering of the function (creation of the National Administrative Unit and Service Centres) had on staffing processes?

4.1 INAC Workforce Landscape

The Department ensures that it has sufficient human resources to achieve its business objectives through integrated planning. INAC's National Resourcing Strategy provides an overarching structure for integrated human resource planning, stating that "integrated, rigorous planning can mitigate the risks of business activities by forecasting and implementing strategies and activities for effective planning, recruitment, retention, career development and talent management (including diversity, employment equity and meeting official languages requirements)." By understanding the current and future human resource needs within the Department, managers and human resource professionals can determine which recruitment, development and retention activities are essential to ensure they meet their current and future staffing needs.

What follows is an overview of INAC's employee population, in order to contextualize the Department's human resources planning priorities, recruitment strategies, and staffing processes examined in the evaluation.

Finding: INAC's workforce population in National Headquarters and the regions have experienced a comparable decline. In terms of composition, the proportion of middle-aged employees at INAC has increased, while the proportion of younger employees has decreased. This is consistent with the general composition of the workforce of the public service.

During the period examined by this evaluation, there was a reduction in the number of full-time equivalents employed in the Department, mostly as a result of cost-containment changes implemented in response to the Deficit Reduction Action Plan announced in Budget 2011.Footnote 29 As a result, the Department's Human Resources Plan for 2014–2020, projected no growth in full-time equivalent levels, and forecasts some further reductions.

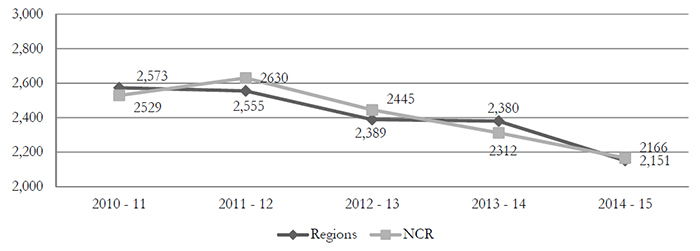

Changes in the Department's population during the period of this evaluation reflect this trend. In 2010–11, the number of indeterminate employees at INAC peaked at approximately 5,100. Between 2010–11 and 2014–15, the population of the Department shrank by approximately 16 percent to 4,100 employees. Figure 4 shows the change in regional employee levels as compared to the population in National Headquarters.

Figure 4: INAC Indeterminate Employee Population by Location, 2010-11 to 2014-15*

* Source: INAC internal program data. Provided by HRWSB, Services Delivery and Data Integrity Directorate.

Text alternative for Figure 4: INAC Indeterminate Employee Population by Location, 2010-11 to 2014-15*

This graph shows the change in INAC's Indeterminate Employee population in the National Capital Region and Regional offices from 2010-11 to 2014-15. The x-axis is labelled by fiscal year, and the y-axis shows the population count. From 2010-11 to 2014-15, both Regional and NCR indeterminate populations decreased.

For the Regional offices from 2010-11 to 2014-15 the population was 2,573; 2,555; 2,389; 2,380; 2,151. For the National Capital Region in the same years, the population was 2,573; 2,630; 2,445; 2,312; 2,166.

Qualitative evidence indicated a widespread belief that workforce reductions had a larger impact on regional offices than on National Headquarters; however, internal program data indicates that the difference between these two population changes was negligible. Regional populations were reduced by 16 percent whereas the National Headquarters population was reduced by 14 percent. The discrepancy between quantitative data and interviewee perception may be in part due to structural changes implemented in response to DRAP intended to streamline management in the Department.

| Age Cohort | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 | 2.1% | 1.9% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 0.9% |

| 25 - 34 | 23.9% | 23.4% | 22.0% | 20.4% | 18.0% |

| 35 - 44 | 30.2% | 31.0% | 32.5% | 33.2% | 33.8% |

| 45 - 54 | 28.6% | 28.5% | 30.3% | 31.0% | 31.8% |

| > 55 | 15.0% | 15.0% | 13.9% | 14.4% | 15.5% |

| Average Age | 43.07 | 43.23 | 43.41 | 43.81 | 44.43 |

*Source: INAC, Service and Data Integrity Directorate |

|||||

In addition to a decrease in the number of its employees, the distribution of INAC's workforce has also changed. Table 1 shows that the average age of the workforce remained relatively constant from 2010–11 to 2014–15; however, the bulk of employees, who are concentrated in the middle age cohorts of 35 to 44 and 45 to 54 has grown from 59 percent in 2010–11, to 65 percent in 2014–15. Conversely, the number of employees between the ages of 25 and 34 has decreased by 5.9 percent: from 23.9 percent of the INAC population in 2010–11 to 18 percent in 2014–15.

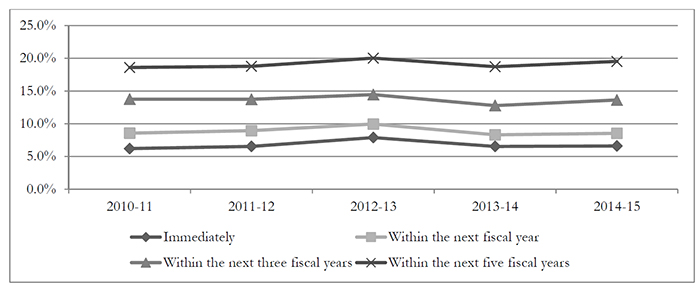

This is consistent with trends in the public service's overall demographics, which has shifted towards employees being of older age groups, and fewer younger employees.Footnote 30 With respect to retirement activity, data in Figure 5 shows that the proportion of indeterminate employees that are eligible to retire both at present and into the future has remained relatively stable, with a marginal increase from 2010–11 to 2014–15.

Figure 5: Percentage of INAC's Indeterminate Population Eligible to Retire, 2010-11 to 2014-15

* Source: INAC, Service and Data Integrity Directorate

Text alternative for Figure 5: Percentage of INAC's Indeterminate Population Eligible to Retire, 2010-11 to 2014-15

This line graph shows change in INAC's indeterminate population eligible to retire in four cohorts: immediately; within the next fiscal year; within the next three fiscal years; and within the next five fiscal years. The x-axis is labelled by fiscal year form 2010-11 to 2014-15. The y-axis is labeled by percentage from 0% to 25%. Lines for all cohorts are nearly flat and horizontal across the graph: approximately 25% are eligible to retire in the next five years; approximately 14% are eligible to retire within the next three years; approximately 9% are eligible to retire in the next fiscal year; and approximately 6% are eligible to retire immediately. All cohorts experienced a slight increase of approximately 1 percentage point in fiscal year 2012-13.

4.1.1 Vacancies

Finding: Overall, vacancies are increasing across the country, particularly in the northern regions. Despite views by non- managers that time consuming staffing processes were resulting in the use of more determinate (term, casual, etc.) workers to fill vacancies, the ratio of indeterminate to determinate employees has remained constant in both National Headquarters and regions.

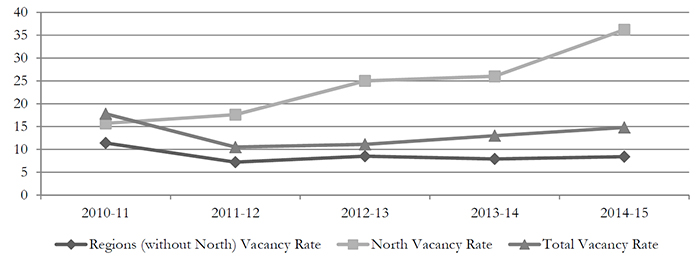

During the period covered by this evaluation, vacancy rates across the Department increased slightly. Figure 6 shows changes in vacancy rates over time. The average vacancy rate increased from 10 percent in 2011–12 to approximately 15 percent in 2014–15, leaving average vacancy rates below the levels observed in 2010–11. By contrast, vacancy rates in INAC's offices located in the northern territories have seen substantial increases from 15 percent in 2010–11 to 36 percent in 2014–15, as shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Northern and Regional Vacancy Rates Comparison, 2010 – 11 to 2014 – 15.

Text alternative for Figure 6: Northern and Regional Vacancy Rates Comparison, 2010 – 11 to 2014 – 15.

This line graph compares vacancy rates in the Northern Region; all Regions excluding the North; and departmental total vacancy rates on average. The x-axis is labeled by fiscal year form 2010-11 to 2014-15. The y-axis is labelled by percentage from 0 - 40%. The lines indicating Non-northern regional vacancy rates and departmental averages are relatively flat over the five year period. The line for Northern vacancy rates is highest on the graph and upward sloping, showing an increase from 15% vacancy in 2010-11 to 36% in 2014-15.

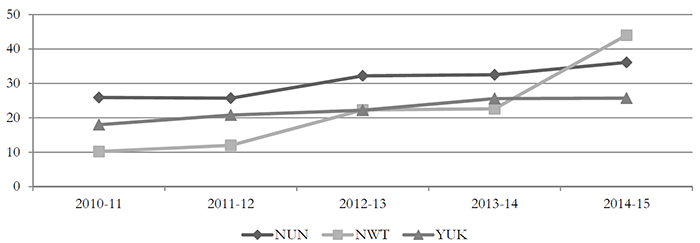

Figure 7: Vacancy Rates by Territory, 2010–11 to 2014–15.

Text alternative for Figure 7: Vacancy Rates by Territory, 2010–11 to 2014–15

This line graph compares vacancy rates in the Northern Region by territory, including Nunavut, Northwest Territories and Yukon. The x-axis is labelled by fiscal year from 2010-11 to 2014-15. The y-axis is labelled by percentage from 0-50%. The lines indicating vacancy rates in each territory are upward sloping.

- Nunavut's vacancy rates increase from approximately 27% in 2010-11 to approximately 31% in 2012-13, and then to approximately 35% by 2014-15.

- Vacancy rates in the Yukon increase steadily from approximately 19% in 2010-11 to approximately 25% in 2013-14 and remain stable.

- Vacancy rates in the Northwest Territories are approximately 10% in 2010-11, then increase to approximately 20% in 2012-13. The vacancy rates increase again to approximately 43% in 2014-15.

While vacancies have increased in all three northern territories, the change was most significant in the Northwest Territories. Vacancies in this region spiked between 2013-14 and 2014-15, coinciding with devolution of additional responsibilities to the Government of the Northwest Territories. Devolution resulted in a loss of 30 percent of regional staff, as illustrated in Figure 7, and a number of these vacancies were at the senior management level. At the end of the time frame examined by the evaluation (2014–2015), the region was continuing efforts to develop and implement a post-devolution organizational structure and plan to fill vacancies.Footnote 31

Point for Consideration: The Department should closely monitor and assess vacancy levels in the North to manage the risk that high vacancies in these regions will negatively impact northern staff and programming.

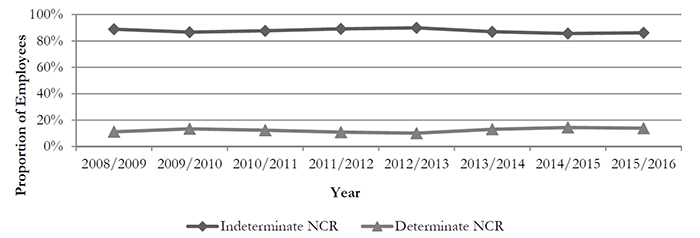

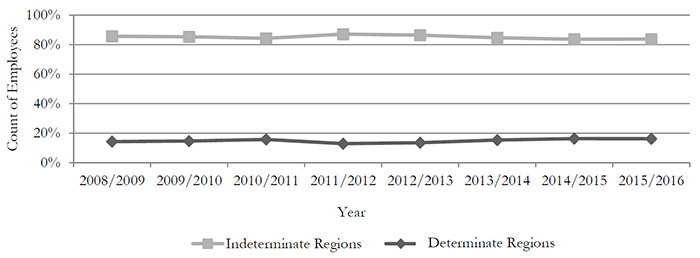

Throughout these changes in population, the ratio of indeterminate to determinate staff (temporary or term staff, including students, seasonal, and casual employees), has remained constant and comparative in both the National Headquarters and the regions (See Figures 8 and 9 below). At National Headquarters, 88 percent of employees are indeterminate and 12 percent are determinate. In the regions, 85 percent of employees are indeterminate and approximately 15 percent are determinate.

Figure 8: Proportion of Indeterminate to Determinate Staff, National Headquarters (2010-11 to 2014-15)*

*Source: HRWSB Internal Program Data – Service and Data Integrity Directorate

Text alternative for Figure 8: Proportion of Indeterminate to Determinate Staff, National Headquarters (2010-11 to 2014-15)*

This line graph shows the proportion of INAC’s indeterminate staff compared to determinate staff at National Headquarters from 2010-11 to 2014-15. The x-axis is labelled by fiscal year from 2008-09 to 2015-16. The y-axis is labelled by percentage from 0 – 100%. The lines for both determinate and indeterminate staff proportions are flat over the 8 year period are flat. At National Headquarters, 88% of employees are indeterminate and 12% are determinate.

The consistent ratio of indeterminate to determinate (term or temporary) staff in both the National Headquarters and the regions suggests that where vacancies arise for indeterminate positions, they are being replaced with indeterminate employees or remaining vacant. This is contrary to the perceptions of non-HR manager interviewees and group discussion participants, some of whom suggested that indeterminate positions were either filled by determinate staff or remaining vacant, because the staffing process for indeterminate positions was too time-consuming, and hiring casual workers was easier.

Figure 9: Proportion of Indeterminate vs. Determinate Staff, Regions (2010-11 to 2014-15)

Text alternative for Figure 9: Proportion of Indeterminate vs. Determinate Staff, Regions (2010-11 to 2014-15)

This line graph shows the proportion of INAC’s indeterminate staff compared to determinate staff in the Regions from 2010-11 to 2014-15. The x-axis is labelled by fiscal year from 2008-09 to 2015-16. The y-axis is labelled by percentage from 0 – 100%. The lines for both determinate and indeterminate staff proportions are flat over the 8 year period are flat. In the Regions, 85% of employees are indeterminate and approximately 15% are determinate.

4.2 INAC’s Activities and Tools to Attract and Recruit Qualified and Experienced Employees

The Common Human Resources Business Process does not include a full definition for the term 'recruitment', but rather describes a series of processes in the category of "Staffing and Employee Integration." This step in the Common Human Resources Business Process value chain includes all activities related to renewal of departmental workforces: planning for recruitment, attracting applicants; screening applicants and assessing those who meet the selection criteria; selecting candidates for employment and extending offers; and, documenting and integrating new employees.Footnote 32 This section of the report reviews the phases of recruitment managers would undergo with support from professionals within the Department, moving from planning to attracting to hiring and staffing new employees.

INAC's National Resourcing Strategy emphasizes the importance of recruitment, both internal and external, to ensure workforce renewal as current employees leave their positions. The National Resourcing Strategy identifies the following key priorities for recruitment and staffing:

- the use of collective staffing pools and generic Statements of Merit Criteria to achieve efficiencies in staffing;

- increased bridging mechanisms to hire students where possible, and use of recent graduate recruitment programs offered by the Public Service Commission;

- support for Indigenous hiring, particularly outreach activities where there is strong representation of Indigenous students and other employment equity groups; and

- addressing the unique recruitment needs in northern regions.

Branches and regional offices across INAC achieve these goals by leveraging the recruiting activities described below.

Student Recruiting

INAC participates in student recruiting to help renew the workforce as employees leave their positions. The Department participates in Public Service Commission – recognized student employment programs, including the Federal Student Work Experience Program, co-operative education programs, and the Research Affiliate Program. Students who complete one of these Public Service Commission-recognized programs with the Department are eligible for "bridging" up to 24 months after the completion of their studies.Footnote 33 Student bridging allows managers to recruit individuals who already have valuable work experience and knowledge of the Department.Footnote 34

The Department also leverages recruitment programs designed to encourage departments to hire recent university graduates at all levels. Managers are encouraged to use the Public Service Commission Post-Secondary Recruitment inventory. The organization also participates in Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program and Financial Officer and the Internal Auditor Recruitment and Development Program run by Public Service Commission. These programs provide an inventory of pre-screened and qualified university graduates for different positions within INAC.

Northern Recruitment

As demonstrated by high vacancy rates in the northern territories, the Department often faces challenges recruiting for positions located in Canada's North. Lower rates of graduation in secondary and post-secondary programs, a younger and more mobile workforce, and elevated cost-of-living contribute to difficulties attracting qualified and representative candidates for northern-based positions.

INAC has taken several steps to support northern recruitment in the five years covered by this evaluation. In 2013, it established an internship program in partnership with the Nunavut Arctic College. The internship is a Public Service Commission-recognized student work program that provides the possibility of bridging for students, thus, building a pool of experienced and educated candidates in the North.Footnote 35 A similar pilot initiative targeted towards on-the-job training for Nunavut Land Claim Agreement beneficiaries called the Inuit Learning and Development Pilot Project was also launched in 2013; however, this initiative is not Public Service Commission recognized. Participants are therefore not eligible for student bridging.

4.3 Attracting and Recruiting Indigenous Employees at INAC

Finding: While the Department has not yet achieved 50 percent representation by Indigenous peoples, their level of representation is significantly higher than the workforce market representation, and INAC has made progress on its objective.

Indigenous recruitment levels within both INAC and the Government as a whole are driven by a number of factors. Under the Employment Equity Act, there are provisions to protect the rights of designated groups, including Indigenous peoples. To be eligible for participation in an appointment process targeted to designated groups, an individual is required to self-identify, i.e., declare as a member of a specific group.

INAC's Corporate Business Plan provides direction and focus with respect to human resourcing activities within the Department. One of its key strategic objectives is to "provide a cohesive and coordinated approach to AANDC's resourcing needs and planning to ensure a workforce that is competent, impartial and representative of the Canadian population with particular emphasis on critical needs and Indigenous peoples." By this, it is understood that the Department should seek to ensure that its workforce includes Indigenous representation.

In fact, going well beyond the stipulations of the Employment Equity Act, INAC committed to a 50 percent Indigenous Hiring Strategy in order to achieve a workforce that is representative of its Indigenous partners. The 50 percent commitment was an aspirational target; the result of a Letter of Understanding that INAC signed in 1994 with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs of First Nations. According to the document:

…the Department will make every reasonable effort to reach an objective of 50% hiring share for Aboriginal peoples until the Department meets this objective. The Department undertakes to make every effort to ensure that Aboriginal peoples are equitably represented across all of the occupational groups and levels in the Department, including management positions."Footnote 36

As shown in Table 2 – INAC workforce Employment Equity Representation, the Department has achieved workforce employment levels that exceed workforce market representation. It also shows that the Department experienced a slight increase in its Indigenous representation from 2010–11 to 2014–15. If compared to Indigenous representation when the Letter of Understanding was signed with Manitoba Chiefs in 1994, (i.e., 15 percent), the Department has achieved an increase of 14 percent from 1994, an approximate 1.5 percent increase per year. This suggests that if a similar trend were to continue and INAC experienced similar yearly increases in the future, it could achieve 50 percent representation in less than 15 years. This, therefore, could reflect a long-term objective for the Department.

| 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Indigenous Employees | N/A | N/A | 1,352.00 | 1,303.00 | 1,242.00 |

| Percentage of Overall Employees | 28.4% | 28.7% | 30.0% | 29.1% | 29.3% |

| Workforce Market Availability of Indigenous Employees | 6.9% | 6.9% | 5.7% | 6.0% | 5.1% |

| Percentage of Indigenous Employment Levels Exceeding Market Availability | 21.5% | 21.8% | 24.3% | 23.1% | 24.2% |

* Source: INAC Human Resources Corporate Dashboards, 2010 to 2015Footnote 37 |

|||||

4.3.1 Indigenous Workforce Representation

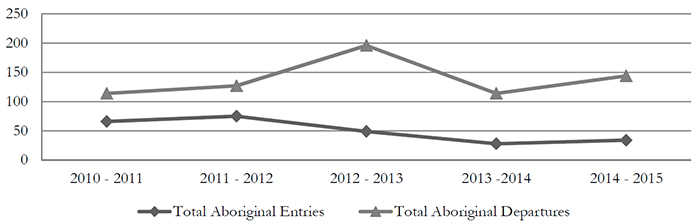

While Indigenous representation in the INAC workforce has remained stable over the past five years given workforce adjustments, the absolute number of Indigenous people working in the Department has declined. As depicted in Table 3, there was a marked decline in Indigenous entries to the INAC workforce between 2011-2012 and 2013-2014, with a slight increase in 2014-15. Whereas Indigenous entries were at approximately 17 percent, they have declined to just over 13 percent.

| Workforce | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entries | 17.17 | 17.22 | 15.76 | 12.65 | 13.45 |

| Departures | 22.81 | 23.71 | 26.32 | 24.89 | 22.53 |

*Source: HRWSB Quarterly Dashboard Reports. Q4, 2010-11 to 2014-15Footnote 38 |

|||||

Finding: In the absence of a positive change in Indigenous hiring trends, development and retention, under the assumption that INAC's workforce stabilizes, the Department may not experience an increase in Indigenous workforce representation as per departmental targets. In addition, there are a number of challenges to Indigenous recruitment, including a lack of awareness of opportunities, and the geographical remoteness of First Nations communities.

4.3.2 Challenges to Indigenous Recruitment

Interviewees and group interview participants identified that there was a lack of qualified Indigenous applicants for many positions. Many positions in the federal public service require undergraduate or graduate degrees. Based on Census data it is known that approximately 1.4 million Canadians self-identified as Indigenous, comprising approximately four percent of Canada's population. Forty-eight percent of Indigenous people aged 25 to 64 in Canada had a certificate, diploma or degree from a trade school, college or university. The comparable percentage for non-Indigenous counterparts was 65 percent.Footnote 39 Thus, fewer Indigenous are eligible for employment in the federal government.

Additionally, interviewees noted lower levels of Indigenous representation in student work placements. They described low numbers of Indigenous co-op students, resulting in fewer Indigenous employees available for bridging, and also low levels of Indigenous participation in the Federal Student Work Experience Program.

It was felt by evaluation participants that Indigenous youth, in particular, are not always aware of programs similar to the Federal Student Work Experience Program and other student employment programs that exist for the recruitment of Indigenous students. Interviewees based this assertion on firsthand experience obtained from conducting outreach at local universities. According to respondents, some Indigenous students did not view self-declaration as beneficial, or were not aware of the purposes and benefits of Employment Equity self-declaration.

Participants in focus groups and key informant interviews noted that gaps in information about Indigenous-specific recruitment programs exist within some First Nations communities. They felt that additional communications between the Department and Indigenous communities as a whole would be beneficial. These challenges, according to interviewees and focus group participants, are emphasized by difficulties contacting potential Indigenous employees as well as individuals being reluctance to move away from home communities for work.

4.3.3 Indigenous Recruitment Initiatives

INAC's role in the recruitment of Indigenous peoples, both to the Department and to Government as a whole, was an area touched on by the evaluation. Initiatives in which the Department participates include, as an example, the Indigenous Workforce Participation Initiative. The Indigenous Workforce Participation Initiative was launched in 1991 and responsibility for it is shared between INAC and the Treasury Board Secretariat. Its mandate is to increase the participation of Indigenous peoples in the labour market. It does this by supporting individuals and organizations that share the goal of breaking down barriers and overcomin the hurdles (real or imagined) that deter the employment of Indigenous peoples.

As part of its Human Resources Strategy, which includes an Indigenous Hiring Strategy that is developed in consultation with the Committee for the Advancement of Native Employment, INAC participates in career fairs, including those of colleges and universities. The participation in such activities is deemed by INAC as an efficient way to maintain a connection and visibility with potential Indigenous candidates for the future.Footnote 40 With its focus on recruitment, development, and retention, interviewees noted that the Committee for the Advancement of Native Employment prioritizes working toward the 50 percent Indigenous employee target. The Committee for the Advancement of Native Employment's prioritization also complements the Department's efforts to establish a workforce that reflects the diversity of Canada and is linked to the Deputy Minister's Aboriginal Workforce Initiative, which was implemented in 2007.

Through the Workforce Initiative was developed the Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative, in 2009. Its goal is to build leadership capacity among Indigenous employees in executive feeder groups. The Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative is further addressed under Section "5.0 Evaluation Findings – Development."

The Department maintains a Statement of Roles and Responsibilities for Hiring Aboriginal Peoples, accessible to all employees at the Department through its intranet. This document outlines key responsibilities of the Deputy Minister, the HRWSB, sub-delegated managers, and advisors towards achieving increased levels of Indigenous representation across INAC. Most importantly, this document supports some agreements, including the Letter of Understanding INAC signed with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, and various land claim agreements.

Flexible work arrangements also exist to encourage recruitment of Indigenous employees where Indigenous peoples living on-reserve are allowed to work from a remote office. The Department also provides flexible work arrangements such as leave without pay and assignment opportunities to Indigenous employees who would prefer to take a leave from INAC and work in their communities.

Many sectors reported that other approaches taken include a focus on hiring Indigenous students in order to promote Indigenous employee hiring. Respondents note that this, however, is sometimes difficult due to the limitations in isolating self-identified individuals in the Federal Student Work Experience Program inventory. To enhance Indigenous recruitment, some INAC branches indicated that they are working closely with university cooperative education programs and university Indigenous student groups in order to improve the pool of Indigenous applicants. As noted by respondents, universities are also aware of this gap and have begun dedicating cooperative education positions or Indigenous peoples to help this partnership.

Currently, INAC National Headquarters has a Liaison with the Indigenous Centre of Excellence at the Public Service Commission. The Indigenous Centre of Excellence offers specialized staffing and assessment services aimed at recruiting Indigenous persons. INAC communicates with the Indigenous Centre of Excellence and discussions center on outreach and awareness (i.e., applying to the public service and to INAC employment offers). For example, the two entities attend job fairs at universities and conferences to recruit Indigenous students.

Regardless of the efforts made, some evaluation participants felt that Indigenous recruitment efforts have seen a decline since the implementation of DRAP. It was felt that the Department has not been in a recruitment mode, although also a sense that it might return to one in the near future. There was general interest in seeing the Department reengage and expand its activities in this area.

4.3.4 Indigenous Student Recruitment

The Department also leverages student recruitment to support Indigenous representation within INAC. In addition to the initiatives described above, the Department provides an "Indigenous student incentive" wherein managers who hire Indigenous summer students are eligible for a 50 percent reimbursement of the student's wages.