A new Shared Arctic Leadership Model

From Mary Simon, Minister's Special Representative

Submitted March 2017

The opinions and views set out in this independent report are those of Mary Simon, the Minister's Special Representative on Arctic Leadership. They are not necessarily the opinions or views of the Government of Canada. To obtain a full copy of Ms. Simon's final report in Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, Dene, or Cree, please contact us.

Table of contents

Introduction and executive summary

I want to begin by thanking Minister Bennett for this opportunity to provide advice toward the development of a new Shared Arctic Leadership Model. Minister Bennett asked me to engage with elected Arctic leaders and their senior staff, youth, land claims organizations, scientists, representatives of industry, and non-governmental organizations, and to provide advice on two important topics:

- new ambitious conservation goals for the Arctic in the context of sustainable development

- the social and economic priorities of Arctic leaders and Indigenous peoples living in remote Arctic communities

The importance of the information received during the engagement process and of my advice was reinforced in December 2016, when Prime Minister Trudeau committed to developing a new Arctic Policy Framework, with Northerners, territorial and provincial governments, and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people, focused on priority areas identified under my Minister's Special Representative (MSR) mandate, including education, infrastructure, and economic development. Accordingly, my report is structured in two parts:

- What I heard: Our strengths and challenges in the Arctic

- Developing a new Arctic Policy Framework

Earlier, I submitted an interim report to Minister Bennett on Arctic conservation goals, and I have refined those recommendations for this report.

To begin, I would like to offer some general observations.

Observations and comments

This was an extraordinary assignment. After more than 40 years of leading, negotiating and observing the processes that have shaped the political, social and economic development of the Arctic, my MSR role challenged me to take a critical look at where the Arctic is today, and what is next for this exceptional region of Canada.

Leaders across the Arctic were candid with me about the particularly complex mix of issues they are confronting today. Revealed in many of my discussions was a common thread: the very real concerns and uncertainties caused by climate change. Canada is an Arctic nation, and shouldering a disproportionate level of impacts because the Arctic is warming at close to twice the global average rate. I heard repeated accounts of the impact of a warming Arctic on food security, infrastructure, housing, and safety on the land and sea. The message was very clear: an adaptation strategy and implementation plan for the Arctic must become a national priority within Canada's climate change commitments.

Another common thread in my discussions with leaders was the importance of a shift in thinking about the Arctic as a remote, marginal and sparsely populated region of Canada, to thinking about the Arctic as a representation of who we are as an Arctic nation, linked to a new era in intercultural relations, global science and sustainable development. The Arctic is generating a heightened level of global interest. In 2016 for example, the European Union released "A New Integrated Policy for the Arctic." Other circumpolar nations are making investments in broadband, marine infrastructure and education. Canada needs to keep pace. To make this shift, basic infrastructure gaps must be addressed to position the Canadian Arctic as an integral part of the global community. The opening of the Canadian High Arctic Research Station later this year is a huge step forward in positioning Canada to be at the forefront of Arctic research. Now we must keep step in other areas.

A significant number of conversations I had with leaders and other stakeholders circled back to a central premise: healthy, educated people are fundamental to a vision for sustainable development…and fundamental to realizing the potential of land claims agreements, devolution and self-government agreements. While this may seem obvious, I kept returning to two vexing questions:

- Why, in spite of substantive progress over the past 40 years, including remarkable achievements such as land claims agreements, Constitutional inclusion and precedent-setting court rulings, does the Arctic continue to exhibit among the worst national social indicators for basic wellness?

- Why, with all the hard-earned tools of empowerment, do many individuals and families not feel empowered and healthy?

Embracing the magnitude of these two questions, in my opinion, lies at the heart of a new Arctic Policy Framework. I will return to these later in my report.

In my travels across the Arctic it was inspiring to see that our youth held strong and focused opinions on what needs to be done to improve conditions in their families and communities. This is particularly important given the demographic realities of the Arctic. Unlike the rest of Canada, where policy and economics are wrestling with an aging population, the reverse is true in the Arctic. The majority of the population in Arctic communities is under 30 years of age.

At a video youth town hall meeting in Iqaluit, I heard from young people across Nunavut and the NWT, in matter-of-fact terms, about not having enough food in their homes, the devastating impact of suicide on their families and communities, and the urgent need for adequate housing. They also spoke about their vision of the future and I was struck by how speaking Indigenous languages, strong environmental protections, and completing their education figured into this vision.

The recently completed strategic plan of the Qarjuit Youth Council in Nunavik echoed these sentiments:

"To move forward in any aspect in life and in our society, we need to be educated. The youth want to be well with who they are and where they come from. Youth also understand the importance of quality, formal education so they can become active members of their communities and society and have access to all levels of employment in the communities, region or elsewhere if that is what they choose."

It was in these informed and passionate voices that I heard the language of aspiration and change. They recognize the legacy brought by the era of colonialism and residential schools. Theirs is the language of needing to reclaim a sense of identity and self-worth. Today, in varying degrees, there is also evidence of another corner turned. Youth across the Arctic understand that education is a portal to opportunity. They aspire to a quality education equivalent to other Canadians: an education that also reaffirms the central role of their culture and Indigenous languages in their identity as Canadians. A new Arctic Policy Framework, if it is to separate itself from many previous documents on the future of the Arctic, must speak to these young voices in this era of reconciliation.

I feel it is important at this point to remind ourselves of the long history of visions, action plans, strategies and initiatives being devised ‘for the North' and not ‘with the North.' There have been numerous statements by Prime Ministers over the years declaring why the Arctic matters to Canada. Typically, these statements have been reactionary and not visionary. Arctic leaders see the Government of Canada as a partner in finalizing and implementing treaties and land claims, but they want this work completed in a measured and thoughtful way that does not compromise the opportunities related to sustainable development. To achieve this, Arctic leaders must be involved in crafting major decisions. A new Arctic Policy Framework starts with an inclusive, mutually respectful and trustful process that establishes (and keeps to) principles of partnership. I will discuss this in further detail in Part II of my report.

One final observation relates to defining "what is the Arctic?" The confusing and somewhat confounding mix of jurisdictional responsibilities, legal mandates derived from land claims agreements and constitutional reform, self-government agreements and devolution, must be harmonized under a vision for recognizing and supporting the authorities of Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations. One of the first tasks of developing a new Arctic Policy Framework must be to define, within the vision, the political and social geography of ‘the Arctic.' For the purposes of this report, we consider the Arctic to be the entirety of Canada's three northern territories in addition to the Inuit regions of Nunavik and Nunatsiavut.

Part 1: What I heard: Our strengths and challenges

In total, I conducted 65 engagement meetings involving 170 people and received 34 written submissions as part of my MSR mandate. It was not possible in the short time accorded to my mandate to meet with all the leaders.Footnote 1 I was limited in my travels to seeing as many people as possible in 2-3 day visits to regional centres. While I am confident that these discussions provided a solid reflection of the general state of affairs in the Arctic today, the relative importance of issues varies across regions and communities.

I also feel it is necessary to mention three unforeseen events that impacted my work:

- the announcement and creation of an Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee

- the Government of Canada's December announcement to replace the current Northern Strategy with a new Arctic Policy Framework and for it to be informed by my assignment

- the December statement by Prime Minister Trudeau that placed a five-year moratorium on offshore oil and gas activity in the Arctic

In my view, these events, each in their own specific way, inform the development of a new Arctic Policy Framework by re-enforcing how policy for the Arctic should be made: through innovative, adaptive policy solutions and policy-making structures that are built upon a reciprocal foundation of trust, inclusiveness and transparency. I will address this in greater detail later in my report.

Our strengths

My discussions confirmed to me a perspective that I have understood implicitly as an Arctic leader: there exists in varying degrees the experience, knowledge and capacity in Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations to pursue a common vision for the Arctic.

Many Arctic leaders have worked through a range of nation-building exercises from negotiating constitutional rights and land claims, to dividing existing and establishing new governments, to setting up and operating management boards, agencies and institutions of public government. The results speak for themselves.

In the last 40 years, a lot of hard work has produced:

- section 35 of the 1982 Constitution Act, providing constitutional protection to the Aboriginal and treaty rights of Aboriginal peoples in Canada

- new governance models, including a new government in Nunavut

- constitutionally-protected land claims agreements across the Arctic

- devolution agreements concluded with two of three Arctic governments and one in discussion

- negotiation of Permanent Participant status for Indigenous organizations on the Arctic Council

- the emergence of a 21st century economy in the Arctic that includes wide participation by Indigenous-owned companies

- successful models where communities and local champions have taken concrete action on social issues

- Canada's full endorsement of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Calls to Action by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- a concerted effort to promote and protect Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic

There is no other region of Canada that has experienced the breadth and pace of geo-political development in the last 50 years than the Arctic. Capacity and expertise issues do continue to impact certain situations, but this can be addressed through smart, adaptive policy processes. The point here is that a new Arctic Policy Framework has an impressive catalogue of accomplishments to build on.

The other familiar perspective I was reminded of in my travels is the remarkable power of local champions, when individuals and communities take ownership of their problems and work together to bring about changes and see the solutions through. Transformations begin when leaders communicate honestly with citizens about the difficult issues they are facing. Everyone involved in Arctic policy development and implementation must ensure that policies recognize, enable, and support local champions who can lead locally-adapted and locally-driven solutions.

Our challenges

Education and language

"Why should there be a conflict between tradition and modernization? We shouldn’t have to compromise between the two. There is an interest to continue to thrive and strengthen our relationship with our language and culture."

In my experience, achieving consensus on topics of generational importance is never easy. My recent travels across the Arctic confirmed that there might be one exception. Leaders and youth were passionate about the urgent need to protect Indigenous languages while graduating more students with standards at par with the rest of Canada. I heard over and over again that education systems must produce knowledgeable graduates who are confident in their skills and their culture.

This is not a new topic. For years, I have heard Arctic leaders, researchers and advocates sound the alarm over the ‘disastrous outcomes' that will follow from large numbers of poorly educated, unemployed youth. There is now urgency in the voices of Arctic leaders about ensuring that we don't leave a generation of youth behind with poor educational outcomes, struggling with identity and diminished self-worth.

There is a great paradox at work in a number of Arctic regions, and it is found in the job market. We have witnessed across Canada generally the phenomena of fewer and fewer job opportunities for students after graduation from high school, and, increasingly, from university, as well. This is not the case in the Arctic. There are jobs available. What is not available is a steady supply of educated or qualified people in the Arctic to fill them. When I heard from individuals that Inuit and First Nations people hold mostly low-paying service jobs in communities, my thought was immediately "we need to aim higher." There are many professional positions across the Arctic that require a post-secondary education or skills training. Large numbers of these higher-level jobs are occupied by non-Indigenous people, who for the most part do not stay in the Arctic longer than a few years. A recent report by the Office of the Auditor General regarding the Department of Health in Nunavut illustrated this point: in 2015-16 there were more than 500 indefinite positions (or 46.6% of the department's permanent workforce) vacant. Mining industry representatives told me that, in other countries, senior positions were often held by educated, local people. This should be the case in the Canadian Arctic. Only better educational outcomes can substantially improve the ratio of professional positions held by Indigenous peoples in the Arctic. This will take directed effort and it will take leadership and collaboration at all levels of government.

Over the past 40 years, I have witnessed governments and school boards in the Arctic working hard to transform their education systems. There has been progress toward creating made-in-the-Arctic curriculum, north-south partnerships with universities that have graduated teachers, relevant learning resources in Indigenous languages, and creating the enabling legislation to foster culturally-appropriate education systems. However, it has been barely a generation since residential school survivors took the brave and bold step of talking openly about the residential school era, dog slaughters, forced relocations and the subsequent abuse, all of which were disastrous for Indigenous languages and cultures. Education policy in the Arctic struggles with the reality of this residential school legacy and its inter-generational trauma. The consequence of this history is that improving educational outcomes faces a complex web of challenges.

Education policy in the Arctic must strive to be culturally relevant, adaptive, and flexible. The Arctic will need like-minded supporters, informed policy specialists, proactive educators and committed leaders, and significant investment to make this happen.

Improving educational outcomes in the Arctic and supporting Indigenous languages to survive and thrive after years of destructive education policy is, at its core, the highest test of nation building.

The road to healthy, empowered citizens in the Arctic begins and ends with education. Federal policy can support this vision in several key areas:

- enhance support to the pathways into, and out of, the K-12 system

- demonstrate the value to all Canadians of preserving, maintaining and developing our Indigenous languages by providing support and protection

- adapt and enhance skills training policies and programs to the Arctic

- enable Arctic students to participate in the ‘globally-connected world' through online learning, by strengthening broadband

For the pathway into the K-12 system, the role of quality, culturally-appropriate Early Childhood Education (ECE) is fundamental to success. This is an area where Government of Canada could make a significant difference in improving educational outcomes because of the pivotal role ECE serves in grounding children in their indigenous languages and opening the door to engage parents in education. However, I was told that ECE funding levels have remained stagnant for a decade. For Indigenous people, the matter of parental involvement in education is complex. The legacy of residential schools lingers in some families who have not yet developed a confidence in the education system or the skills to support their children's academic learning. Children must come to school rested, well fed, with their homework done and ready to learn. These conditions can be fostered by quality, affordable, culturally-appropriate ECE. Strengthening ECE programming through enhanced and sustained funding agreements is the first bridge toward success in school.

At the other end of the education continuum, Canada continues to be the only circumpolar nation without a university in the Arctic. The interest in establishing a university in the Arctic dates back several decades. There are two circumpolar universities for Canada to learn from - Ilisimatusarfik - the University of Greenland and Sami University College in Lapland. Both institutions are rooted in the idea that universities are transformative places that strengthen the concept of self-determination. They each started small and, with the support of national leadership, they grew.

Colleges across the Arctic have been at the forefront of post-secondary education including introducing adult learning and university programming in a variety of professional disciplines. In the Northwest Territories, the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning has partnered with the University of Alberta, McGill University and the University of British Columbia to create an innovative program that combines on the land learning, promotion of Indigenous languages, and accredits Elders as professors. Satellite programs are currently being developed in other Arctic regions. The innovative thinking and insight of the post-secondary community impressed me, and confirmed to me that the time is now to establish a University of the Canadian Arctic.

One important role the Government of Canada has played for 25 years at the post-secondary level is in supporting Nunavut Sivuniksavut, an Ottawa-based program with proven results. In partnership with Algonquin College in Ottawa, Nunavut Sivuniksavut brings students from Nunavut communities together to study Inuit history, land claims, governance and current issues in a safe and nurturing environment. The program is now being replicated for students from Nunavik. This is a good example of where the Government of Canada has been successful in supporting pathways out of the K-12 system.

For all my working life, I have advocated for the importance of preserving, developing and promoting Indigenous languages. Our Indigenous languages are part of the cultural fabric of our country. In my discussions across the Arctic, it was heart-breaking to hear example after example of our Indigenous languages in Canada at risk of extinction. Even languages formerly considered relatively robust, such as my own language of Inuktitut, are in decline. Indigenous peoples do not want to lose their languages.

The absence of Indigenous languages in schools for many years, and today in many grade levels, combined with the trend towards using English in the home, has had a destructive impact. The pervasive lack of Indigenous languages in government and business has also contributed to this decline. Our languages are being forced into extinction. Justice Thomas Berger, in his 2006 The Nunavut Project provided this frank assessment:

"The Inuit of Nunavut are faced with the erosion of Inuit language, knowledge and culture. Unless serious measures are taken, there will over time be a gradual extinction of Inuktitut, or at best, its retention as a curiosity, imperfectly preserved and irrelevant to the daily life of its speakers."

Canada has been a leader in promoting and protecting bilingualism. The principles behind this leadership now need to be applied to Indigenous languages, in a new Arctic Policy Framework.

One of the other observations I made from my discussions across the Arctic is the persistence of lost training opportunities when large infrastructure projects fail to set or meet skills training targets. Impact benefit agreements between Indigenous rights holders and promoters are one approach, though success has been limited. Recruitment, retention and advancement remain challenging. Certification and union regulations are often barriers for engaging local labor. This results in a lost opportunity for building a local workforce and significant amounts of money not ‘staying in the Arctic.' Government investments in infrastructure and housing, for example, need to be pro-active in requiring demonstrations of local skills training.

Education and language recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Make education the cornerstone of the Arctic Policy Framework as the key to healthy people and social and economic progress

- Increase funding for quality, culturally-relevant Early Childhood Education (e.g. Aboriginal Head Start)

- Announce its intent to create a University of the Arctic by striking a representative Arctic University task force to create a vision and business case

- Increase access to a continuum of community-based mental health services for students

- Invest in closing the "digital divide" in order to increase access to online learning and research for Arctic students

- Maintain and expand its support for Sivuniksavut programs in Inuit Nunangat

- Commit to supporting Indigenous languages by working with governments across their programs, school boards, and Indigenous organizations with specific mandates for language preservation and revitalization, to determine where their needs are and where policy and financial support will provide the most benefit

- Require that all federal investments in infrastructure and housing include skills training, apprenticeships and employment

Research and Indigenous knowledge

For many years integrating Indigenous knowledge and western science has been the practice of numerous management boards in the Arctic, and is a requirement of most research projects in the Arctic. The next step in the evolution of scientific practice in the Arctic is linking community-driven Arctic research priorities with national policy development to ensure scientific investments benefit communities and answer key questions facing the Arctic. I firmly believe that the foundation of effective decision-making is good information. In the Arctic, that means being committed to placing equal value on Indigenous knowledge and western science. The new Arctic Policy Framework presents an opportunity to take this to its next level.

Canada's commitment to building the new Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) in Cambridge Bay is a global achievement. CHARS is an unprecedented opportunity to work directly with Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations to pursue, at a minimum, three unique goals:

- showcase to the world the best practices and benefit of integrating Indigenous knowledge and western science

- link new investments in research to improving community wellness in the Arctic

- position Canada as a world leader in Arctic climate research

It was disappointing to learn that the 2016-2019 research plan developed by Polar Knowledge Canada had dropped the theme of healthy communities proposed by the Northern Advisory Panel. As I noted earlier, a significant number of conversations I had with leaders and other stakeholders circled back to a central premise: healthy, educated people are fundamental to a vision for sustainable development so it is paramount that the CHARS plan reflect this priority.

The credibility of the CHARS initiative to Arctic peoples rests in part on the work CHARS can do to highlight the importance of working with Indigenous peoples and organizations. Specifically, this means applying Indigenous and local knowledge in research, including curating and archiving existing Indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge mapping, and linking these national archives with regional traditional knowledge repositories.

CHARS research capacity should also be connected to the large-scale public investments in research that precede decisions on marine and land use, notably hydrographic mapping and geoscience. I was told about major road and marine projects that lack basic data and information to advance to an environmental assessment process. I also learned about the importance and challenge of environmental monitoring after roads are constructed. CHARS research capacity should directly link to existing Arctic learning institutions, including Aurora College, Yukon College, Nunavut College, and Dechinta: post-secondary learning institutions that are well positioned to offer skills training and professional development for specific research initiatives.

Research and Indigenous knowledge recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Establish and support a Centre for Indigenous and Local Knowledge as a core element of the Canadian High Arctic Research Station to link to and support regional cultural institutes and programs

- Direct Polar Knowledge Canada to include the theme of improving the health and wellness of families (physical and mental health, housing, food security etc.) in its research priorities

- Ensure appointments to the Polar Knowledge Board are inclusive and representative of Arctic peoples and that priority-setting exercises are informed by representative input from Arctic peoples, governments and Indigenous organizations

- Invest in the hydrographic data collection necessary to establish low-impact Arctic marine shipping corridors

- Partner directly with Indigenous organizations and territorial governments to create vessel management and monitoring programs to ensure increased ship traffic benefits Arctic communities

- Increase the level of geoscience spending in the Arctic to expand the availability of baseline mapping and geological research

Closing the infrastructure gap

No matter who I talked with, the topic of closing infrastructure gaps was often at, or close to, the top of the list to improve socio-economic conditions. The Arctic is unlike any other region of Canada in its infrastructure needs because of its geography and sheer expanse. With 68% of Canada's coastline and roughly 40% of this country's landmass, the infrastructure needed to access resources lags far behind other regions of Canada and other circumpolar nations. In the Yukon, all but one community is accessible by road. In the NWT, more than half of the communities can only be reached by air, or seasonally by water or ice-roads, while in Nunavut, communities are accessible only by air or annual open-water sealift operations. The rich natural resource potential of the Arctic requires a significant infrastructure investment simply to access the resources. The priorities vary across the Arctic, but they share three common concerns related to national infrastructure programs:

- federal infrastructure programs fail to recognize the unique challenges of building infrastructure in the Arctic, the need for the Arctic to ‘catch-up' to other regions of Canada, and the punitive nature of per capita funding formulas without base funding allocations. (There is irony in the fact that Canada has built institutions of public government in the Arctic but has yet to finish building the basic infrastructure to the standard of a first world country.)

- some ‘national' infrastructure programs have virtually no application to the Arctic (e.g. mass transit), and there is no equivalent program geared to address the specific needs of Arctic communities

- climate change is accelerating threats to existing infrastructure: melting permafrost is directly impacting the integrity of building foundations, roads, runways, pipelines and coastal infrastructure. Infrastructure programs need to provide for mitigation and adaptation construction research in response to these rapidly changing conditions

Closing the infrastructure gap recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- With Arctic governments and Indigenous leaders, develop criteria for Arctic infrastructure projects that reflect the singularly unique context for infrastructure spending, the 'catching up’ nature of the infrastructure gap in the Arctic, and that corrects for the punitive nature of per capita allocations without base funding

There are three areas of ‘infrastructure spending' that people I spoke with felt the Government of Canada had a singularly important role to play, in both closing gaps and setting the stage for the next era of Arctic development.

Broadband

"From the economy and healthcare to scientific research and public safety, broadband has the potential to positively affect nearly every sector of society. It facilitates and enhances our daily lives in ways once unimaginable. Indeed, broadband has the power to transform society and enable new and more robust ways of interacting with one another."

Although it was clear in my discussions with Arctic leaders that they each have a long list of infrastructure needs, it was discussions about a leap forward in broadband that presented the most intriguing transformational ideas. To be realized, that transformative potential in Canada's Arctic requires significant federal leadership in the coming years.

Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) defines broadband as an "Internet service that is always on (as opposed to dial-up, where a connection must be made each time) and offers higher speeds than dial-up service." (Telecommunications Infrastructure Working Group, Arctic Economic Council, Arctic Broadband: Recommendations for an Interconnected Arctic [Arctic Economic Council, Winter 2016], p. 6).

Fortunately, there is a comprehensive assessment on what it will take to address the connectivity gaps in the Arctic. I was directed to the 2011 Arctic Communications Infrastructure Assessment Report that includes detailed maps listing the varying communications services available in the Yukon, NWT and Nunavut. The report contains recommendations for addressing the gap between what is needed and what is affordable beginning with a national commitment to service parity among Arctic communities. More recently in 2016, the Arctic Economic Council (AEC) published "Arctic Broadband: Recommendations for an Interconnected Arctic." The Arctic Economic Council's report provides an excellent comparative analysis of where the Canadian Arctic stands with broadband relative to other circumpolar nations, and provides a breakdown of available technologies and financing possibilities. In terms of where the Canadian Arctic is today relative to the rest of Canada the report says the following:

"According to the Government of Canada, over 99 percent of Canadian households currently have access to broadband with speeds of at least 1.5 Mbit/s. However, only 27 percent of households in the rural Nunavut region have access to broadband. The Connecting Canadians program, part of Digital Canada 150, will invest up to $305 million to extend broadband access throughout the country with the goal of bringing speeds of at least 5 Mbit/s to an additional 280,000 homes in rural and northern regions of the country"

Northern governments have been calling for investments in broadband as a critical element to the future of accessing and providing government services and promoting economic development. Significant advances have already been made in telehealth in all territories, with the Northwest Territories leading the way. However, financing broadband expansion in the Arctic remains a huge stumbling block. The Connecting Canadians Program, even with an increase of $500 million in Budget 2016 is insufficient to address the sheer scale of closing the broadband gap in the Arctic. Currently the Arctic is limited to accessing funding for broadband through the provincial-territorial infrastructure component of the Building Canada Fund, or through public-private partnerships. Inuit organizations in Nunavut and Nunavik have recently proposed that broadband be considered a component of ‘national infrastructure' under the Building Canada Fund, referring to the transformative importance of broadband to Canada's Arctic as equivalent to a ‘ national railway.'

Other circumpolar nations have seized on the economic potential driven by global digitization and have made quick strides (relative to Canada) to close the broadband gap. The Arctic climate is well-suited for digital data centres because the cold climate requires less energy to cool down servers.Footnote 2

There has been a great deal of collaborative work put into assessing Canadian Arctic broadband needs relative to other Canadian jurisdictions and the broader circumpolar context. I would also like to highlight the example of Cisco's Connected North, which clearly demonstrates how increased broadband access improves learning opportunities and mental health services. This, taken together with the upside of the possibilities unlocked by more robust broadband, the evident interest of Arctic governments and Indigenous economic development corporations in investing in broadband, demonstrates why a broadband strategy must form a core pillar of the Arctic Policy Framework. Broadband is also an excellent example of why the Arctic Policy Framework must be a collaborative effort not just with Arctic leadership, but across federal government departments.

Broadband recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Commit to a goal of service parity in broadband by investing in the recommendations found in the 2011 Arctic Communications Infrastructure Assessment Report along with the 2016 Arctic Economic Council (AEC) report Arctic Broadband: Recommendations for an Interconnected Arctic

- Revise its infrastructure program criteria to allow for Arctic broadband to be considered a project of ‘national infrastructure' under the Building Canada Fund

- Build digital infrastructure and programming into any federal initiatives in education, language and mental health support

Housing

Though the extent of the housing deficit in the Arctic varies from region to region, there is a general consensus that the housing shortage represents a public health emergency. The lack of affordable housing undermines efforts in improving physical and mental health, education outcomes, and in addressing issues of domestic violence and poverty. The housing deficit increases as you travel west to east, with the most pronounced problems in Nunavut and Nunavik, where costs are significantly higher due to the lack of roads and ports. However, the urgent need to close the housing gap is heard throughout the Arctic.

While I was travelling for this assignment, the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples released a well laid-out report based on 2016 hearings on the extent of the housing crisis in Inuit Nunangat.

The report paints a stark picture of the issues leaders in the Arctic are dealing with, that, if not addressed, stand to doom housing in a perpetual crisis. With the Government of Canada's current commitment to affordable housing, this is the time to further close the gap on access to affordable housing in the Arctic. With the Arctic Policy Framework, there is also an opportunity to address the structural policy issues that are fomenting future crises in housing, as laid out in the Senate report. I realize that housing in the Arctic falls to a number of agencies including the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and provincial and territorial governments. In my view, this is a social issue of such magnitude that it demands leadership and collaboration at all levels and across federal departments.

To say that things aren't being done to close the gap would be wrong. The Government of Canada has made significant investments in Arctic housing in recent years, though serious gaps remain. There have been innovative approaches to address the limitations of the tendering process, which have often resulted in imported construction crews hired to build housing. I was impressed with the results of Makivik Corporation's 15-year housing project negotiated with Canada and the Government of Québec that established a not-for-profit construction division, thereby ensuring that local hiring and contracts stayed within Nunavik. The results have been positive. Building on the elements of success for this model by creating a sustainable infrastructure for Indigenous communities program is the right thing to do. This is an area where there is a great deal of existing expertise in the Arctic. Governments have plans and innovative models for closing gaps; the shortfall exists in budgets for affordable housing, and, as noted by the Senate Committee, in addressing the declining maintenance budgets provided through CMHC.

The Finance Minister's address introducing the new 2017 federal budget contained the following statement:

"And so, it is my privilege to announce that the government will be investing over $11 billion—the largest single commitment in Budget 2017—in support of a National Housing Strategy, to help ensure every Canadian has a safe and affordable place to call home."

I am compelled to reiterate that nowhere in the country is the need greater than for Indigenous peoples, including those in the Arctic.

The budget does make important commitments for housing to the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut governments over the next 11 years, however it is unclear to what degree these commitments are directed to housing for Indigenous peoples. Territorial leaders and Indigenous organizations have acknowledged the importance of this investment, though they have expressed concerns that investments are insufficient to meet the need. Finally, I did not see specific references to investments that would apply either to Nunavik or Nunatsiavut.

Housing recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Act on the recommendations of the findings of the Senate Standing Committee Report on Housing in Inuit Nunangat and work with governments and Indigenous organizations and adapt those recommendations to the other Arctic regions covered by my mandate (which includes the three territories in addition to the Inuit regions of Quebec and Labrador)

- Design and implement multi-year funding agreements compatible with planning, transportation and construction realities in the Arctic

- Adjust policies of northern housing authorities to allow for ways to involve Indigenous peoples in the conceptualization, design, construction, and maintenance of housing in their communities

- Under social infrastructure funds, establish a program to encourage construction of housing for people living with mental illness under a model of community-based support and treatment.

Reducing fossil fuel dependency

"If I was a CEO I would train people in developing and manufacturing renewable resources; I would then provide money, incentives for people and businesses to build renewable resources; would spend money on this because renewable energy doesn’t run out."

There is a striking irony in the Arctic when discussing climate change. The impact of a warming climate is evident in community infrastructure and threatening the hunting and fishing livelihoods of individuals and commercial fisheries. Throughout my travels, I heard concerns about food security in part because a warming Arctic is threatening the abundance and distribution of wildlife and safe access to many traditional inland and marine harvesting areas.

The irony is that Arctic communities are highly dependent on fossil fuels. In most communities, off-grid diesel-fired thermal power plants produce the only source of power for oil-burning furnaces and water heaters. The consequence of this dependency is a sometimes erratic supply of electricity in the communities, no options for residents and businesses to lower energy costs, higher and more complicated rates for electricity and, ultimately, conditions that stall economic development. Hydro-carbon spills during annual sea-based deliveries or from storage tanks are far too common. In a 2014 appearance before the Standing Senate Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources, Indigenous and Northern Affairs stated, "In 2011 it was estimated that Northern communities consumed 76 million litres of diesel fuel for power generation and 219 million litres of fossil fuel, diesel or propane for heating production, resulting in a total of over 800,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually."Footnote 3

Solutions are varied, depending on the region. Nunavik and Nunatsiavut, for example, are surrounded by massive hydroelectric development projects that generate power in the Arctic and send it south. NWT's rivers and lakes contain an estimated 11,000 megawatts of potential hydroelectric power. Similarly, Yukon is looking to expanding hydroelectric power. Yukon College's Yukon Research Centre has recently been awarded Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada funding for an Industrial Research Chair on Northern Energy Innovation to oversee research on renewable energy strategies and options across the Arctic. Connection to existing power grids may be a partial solution in some regions; development of new local power networks with policies to feed into the grid are another. Community-based clean energy generating projects such as run-of-the-river hydro generation are also being studied. Wind power and biomass projects are showing some success. Glencore installed a wind turbine at its Raglan Mine in Nunavik, which is now generating 8,8500MWh of electricity annually. While representing a minor reduction in total diesel consumption, the pilot project has demonstrated that installing and operating wind generators is feasible in Arctic conditions.

Innovation and transition will require major investments. These will likely come from a combination of government and private sector sources. However, these transitions will deliver long-term economic return. They can also have important shorter-term economic benefits for regions and communities. Planning and implementation of solutions should be linked to job creation and economic development for Arctic residents and businesses. Project development and ownership can be established in partnership with organizations and businesses. Energy development must be employed as a lever to create wealth and social development in the regions and communities. All regions have existing Indigenous business groups capable of partnering in the important and necessary shift away from fossil fuels.

In its own planning cycle, the Government of Canada has noted in several policy documents the relationship between a renewed relationship with Indigenous peoples, developing a Canadian Energy Strategy and supporting innovations and clean technologies and investments that lead to healthier, cleaner communities. This culminated on December 20, 2016, as part of the United States-Canada Joint Arctic Leaders' Statement, with the announcement that the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada would lead the development of a plan and timeline for deploying innovative renewable energy and efficiency alternatives to diesel in the Arctic in collaboration with key partners. A 2016-2017 budget set aside of $10.7 million was made to implement renewable energy projects in off-grid Indigenous and northern communities that rely on diesel and other fossil fuels to generate heat and power.

In my view, the Government of Canada can continue to contribute positively to finding solutions for fossil fuel replacement and energy efficiencies in the Arctic by:

- establishing a policy platform with clear objectives, based on partnership with territorial governments and Indigenous organizations

- assigning funds and departmental responsibilities

- supporting opportunities for local businesses

Reducing fossil fuel dependency recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Ensure that the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada-led process announced in December 2016 involve Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations

- Establish a business development fund for Indigenous-led renewable energy and efficiency projects

- Expand and collaborate with the Yukon College and the new Industrial Research Chair for Colleges in Northern Energy Innovation. This NSERC-funded position is further supported by Yukon Energy, ATCO Electric, the NWT Power Corporation and Qulliq Energy. The research will focus on the integration of renewable energy in isolated community grids, energy storage, diesel efficiencies, independent energy valuation, residential and utility partnership, and demand-side management

Continuing the conservation discussion

As directed in my mandate letter, I would like to offer my final, updated recommendations pertaining to achieving a new, ambitious Arctic conservation goal. In my numerous discussions about protected areas in the north there were four central themes:

- the biological abundance of the Arctic must be protected for future generations to benefit from

- there is an expectation that Arctic conservation is tied to building and maintaining strong and healthy communities

- the pace of land conservation has far outpaced ocean protections

- land claims agreements and Indigenous organizations alongside federal, provincial, territorial governments have already identified significant percentages of lands and marine areas with the spirit of conservation in mind.

I would also like to point to the findings of the recently released report by the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development, Taking Action Today: Estabishing Protected Areas For Canada's Future, which discussed the premise that perhaps 50% of Canada's land and marine areas may need to be conserved.

The first step toward any new goal is to adequately take stock of what already exists. For example, the north is covered in land, marine, and species specific planning processes. A set of maps was generated based on existing information on planning areas to ensure my findings utilized and built upon existing conservation efforts (see Appendices 2 and 3). From this exercise, it is evident that land-based conservation initiatives in the Arctic such as the establishment of parks, biodiversity reserves and sanctuaries, and land use planning, have resulted in significant land conservation outcomes. Future initiatives should look for ways to work in partnership with Indigenous regions to better fund, implement and recognize areas already identified in land use plans. They should also emphasize species such as caribou, and habitats and cultural areas of vital importance to Indigenous communities. Caribou are currently experiencing unprecedented population declines across the Arctic. One area that stands out in this regard is Thaidene Nene, on Great Slave Lake. It is a sacred region of the Lutsel K'e Dene.

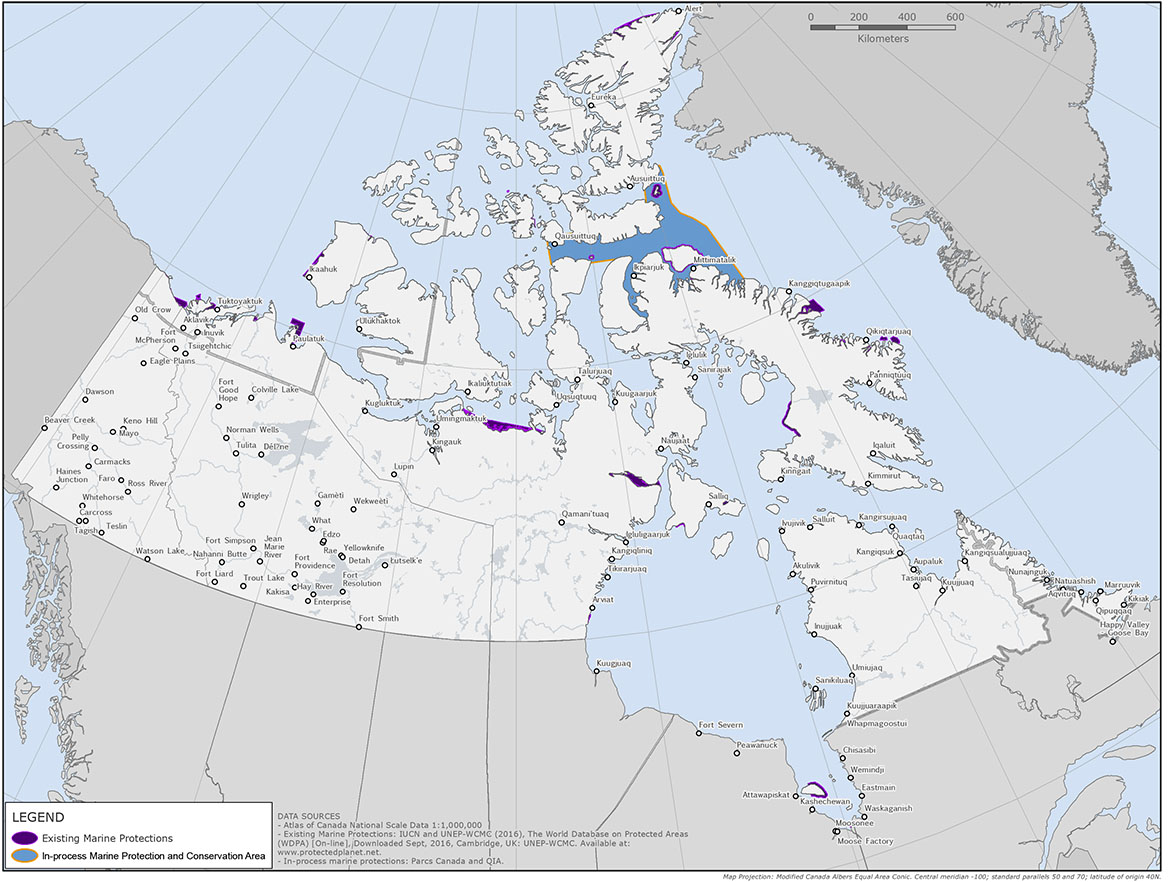

Marine conservation initiatives in the Arctic have not kept pace with land conservation with less than 1% of the waters of Inuit Nunangat under any form of recognized protection (see appendix 4). In spite of having the world's longest Arctic coastline, Canada's Arctic has only two existing marine protected areas, Tarium Niryutait and Anguniaqvia Niqiqyuam. These areas represent less than half a percent of Canadian Arctic waters. Yet, nearly all Inuit communities are situated on the Arctic coastline adjacent to marine areas of ecological and biological importance. Inuit have classified through local planning processes approximately 21% of Arctic waters as requiring distinct environmental management. The federal government, through a mix of planning processes, has identified 55% Arctic waters as ecologically and biologically significant. Maintaining healthy coastal and marine habitats is critical for food security, cultural continuity and increased economic opportunities from fisheries and tourism.

Re-imagining conservation through Indigenous protected areas

I am of the mind that there is a distinctive moment building where the right leadership could spark a conservation paradigm shift in the Arctic. Over the past months, I took note that although the unique Arctic environment is central to many aspects of life and identity, conservation is not sustainable if it competes with economic progress. I also learned about innovative conservation programs, policy, and legislative options that can directly contribute to sustainable, healthy communities.

In research commissioned to support my work, one of those instruments was examined in greater detail: the Indigenous protected area. This background report on Indigenous protected areas investigated the opportunity and implications of Canada becoming the first country in the world to have a legal mechanism to formally recognize Indigenous protected areas. The Indigenous protected area concept has had success in Australia. Across Canada many Indigenous regions have created designations (often through land use planning) that appear to have elements of an Indigenous protected area.

However, the term is not present in any national legislation. It has been interpreted and applied as an important policy concept that can harmonize interests of state and indigenous governments pertaining to regional conservation initiatives. A convergence between Indigenous peoples and conservation, through a rights-based, custodian driven approach, would decolonize conservation and make a significant contribution towards reconciliation.

Indigenous protected areas are based on the idea of a protected area explicitly designed to accommodate and support an Indigenous vision of a working landscape. This kind of designation has the potential to usher in a broader, more meaningful set of northern benefits and bring definition to the idea of a conservation economy. For example, Indigenous protected areas have the potential to serve as a platform for developing culturally-appropriate programs and hiring of Indigenous peoples in a wide range of service delivery including:

- environmental and wildlife monitoring

- vessel management and monitoring

- emergency preparedness and response

- search and rescue

- tourism opportunities

- expanded or new guardians programs

Indigenous protected areas also contribute to healing and reconciliation by:

- supporting communities and individuals in regaining land-based life skills

- reconnecting youth with their cultural traditions and language

- collecting and documenting Indigenous knowledge

- guaranteeing that there will always be ‘places that are theirs'

After completing my engagement process with northern leaders, elected officials, Indigenous organizations, industry and non-governmental organizations, and weighing all submitted material, I have separated my recommendations into two categories. First, I present recommendations required for Canada to meet our stated 2020 land and marine conservation targets. Second, I present recommendations that should serve as the cornerstone of a new, ambitious Arctic conservation goal. If executed correctly, meeting this goal can have a positive impact on communities and regions and future economic prosperity. Working in a measured and thoughtful way that seeks to balance jurisdictional and conservation objectives is now our common challenge.

Final conservation recommendations

Immediate steps towards meeting existing conservation targets

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Expedite the process of completing Tallurutiup TariungaFootnote 4 (Lancaster Sound) as a National Marine Conservation Area using the expanded boundary set out by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association

- Expedite the process of completing Thaidene Nene as a National Park

- Accept the Pikialasorsuaq Commission's recommendation for the creation of an Inuit-led management plan and monitoring process for the entire North Water Polynya and consider recognizing the region as an Indigenous Protected Area

- Develop a "whole of government" approach to terrestrial and marine park-related impact benefit agreements that meets or exceeds best global standards

Indigenous protected areas: Toward a new, ambitious Arctic conservation goal

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Work to formally recognize existing land and marine conservation planning designations as the basis for setting and realizing a new, ambitious conservation goal

- Continue progress toward becoming the first country in the world to have a legal mechanism to recognize Indigenous protected areas

- Work with Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations to conceive a new federal policy directive that sets out a process for the identification, funding and management of Indigenous protected areas

- Identify long-term stable funding to support locally-driven terrestrial guardians and Arctic coastal and marine stewardship programs

- Make a request to the International Union on the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to formally recognize Indigenous protected areas as a valid conservation designation under the "other acceptable conservation measure" category

Part 2: Developing a new Arctic Policy Framework

In my meetings with Arctic leaders, I was confronted frequently with the question of whether my role as the Minister's Special Representative would be viewed by the Government of Canada as a replacement for already established bilateral relationships with the Crown. My response was to say that I viewed my mandate as a means of sharpening the focus on the issues of the day. I made it clear that my work would seek to enhance, not replace, legally-binding agreements or active consultations and negotiations. Once this was understood, conversations quickly turned to expectations of partnership with the Government of Canada.

I feel it is important to note that I encountered in my discussions a profound sense of disillusionment, and sometimes distrust, related to agreements with the Government of Canada, whether it was the slow pace of devolution agreements, conflicts in land claims implementation, or bilateral agreements that by-passed territorial governments. The term co-development of policies with Canada was looked upon with suspicion. My overall impression was that there was a long-standing disconnect between the aspirational intentions and commitments of Ministers, and the paternalistic, at times obstructionist, approach by the bureaucracy to the implementation of these ideas. The strong reaction from northern leaders to the unexpected announcement of the moratorium on oil and gas activities only added to the cynicism I encountered related to federal commitments to partnership.

It was disappointing to see that, even with the great deal of progress in the Arctic that I have previously described, a strong relationship with the Crown is still in its infancy. With every account of a troubled relationship with the Crown, I reflected back to my experience in 1982 negotiating Section 35 of the Constitution Act - what many have described as the watershed moment in the history of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relations in this country. The entrenchment of Aboriginal and treaty rights was a monumental achievement for Aboriginal peoples and for Canada enshrining our recognition as peoples in Canadian law.Footnote 5 It is imperative that the federal government fulfill the intent of Section 35 in the Arctic.

Meeting with many leaders and representatives of organizations in such a short amount of time, I began to hear common messages on how partnerships with the Crown could be more effective. I now present them as the principles of partnership.

Principles of partnership

- Understanding and honouring the intent of Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982: All partners should understand and honour Canada's commitment to upholding Section 35 of the Constitution and strive to achieve forward momentum in defining how Section 35 can be applied to evolving policy and program initiatives.

- Reconciliation: Reconciliation in partnerships and policy-making involves, at a minimum, a commitment to restoring relationships, seeing things differently than before, and making changes in power relationships.

- Equality, trust, and mutual respect: A true partnership has to be built on equality, trust, transparency and respectful disagreement.

- Flexible and adaptive policy: Nation-building in the Arctic will not be found in one-size-fits-all policy solutions. Policies need to adjust and adapt to circumstances.

- Arctic leaders know their needs: Recognize that Arctic leaders know their priorities and what is required to achieve success.

- Community-based solutions: Local leadership must be recognized and enabled to ensure community-based and community-driven solutions.

- Confidence in capacity: An effective partnership has confidence in, and builds on, the capacities that are brought into the partnership, but also recognizes when capacity gaps need addressing.

- Understanding and honouring agreements: The signing of an agreement is only the beginning of a partnership. Signatories need to routinely inform themselves of agreements, act on the spirit and intent, recognize capacity needs, respect their obligations, ensure substantive progress is made on implementation, expedite the resolution of disputes, and involve partners in any discussions that would lead to changes in agreements.

- Respecting Indigenous knowledge: Indigenous and local knowledge must be valued and promoted equally to western science, in research, planning and decision-making.

Developing a new Arctic Policy Framework starts with an inclusive, mutually respectful and trustful process that establishes (and keeps to) principles of partnership. The principles listed above reflect the body of conversations I had with leaders across the Arctic, and should serve as a starting point for discussions related to a new Arctic Policy Framework.

The Inuit-Crown Partnership signed on February 9th by Prime Minister Trudeau and Natan Obed, President of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, in my view, is an example of how transformative policy begins with doing things differently. The success of this new Inuit-Crown Partnership will be measured by the actions that impact the day-to-day lives of Inuit. I congratulate the Government of Canada for committing to this mechanism for taking action on Inuit issues with a new, high-level process.

As I noted earlier in my report, the mix of jurisdictional responsibilities, legal mandates derived from land claims and self-government agreements, as well as devolution in the Arctic, has created a splintered approach to Arctic policy, yet all jurisdictions share common challenges unique to the Arctic. The Arctic Policy Framework process should be tasked with finding a mechanism, perhaps under legislation, or through processes such as a domestic Arctic Forum, where common policy issues can be tackled. This mechanism would not replace any existing legal and political relationships with Canada, but present a better managed and comprehensive process to examine and promote policy responses to Arctic issues. It could also be a forum to discuss horizontal policy responses across a number of federal government departments, or to discuss national policy criteria that are limiting Arctic participation (e.g. Connecting Canadians Program) and precluding the ability of the Arctic to catch-up with other regions of Canada.

There were a number of policy issues raised with me as I travelled the Arctic that spoke directly to the central premise that community wellness drives a vision for sustainable development. It is clear that many threads gather around community wellness. It would be my hope that these issues, including the rising rates of incarceration, the alarming trend in child welfare in which children are being fostered to homes out of the community, and the growing need to adequately address community elder care, are reflected in policy discussions at an Arctic Forum level, and in the collective responses of governments at all levels.

The road to reconciliation will take many paths, but one aspect that seems to be consistent in discussions is there needs to be changes in power relationships to see and do things differently.

A new Arctic Policy Framework must address, not only principles of partnership and key policy focus areas, but also fundamental process questions as to ‘how' the Arctic participates in priority-setting and decision-making in ways that differ from the past.

Developing a new Arctic Policy Framework recommendations

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Convene a summit of northern Premiers and Indigenous leaders with the Prime Minister and key Ministers to discuss a process for developing a new Arctic Policy Framework

- Develop, with Arctic leaders, principles of partnership for policy processes

- Commit to greater action to address the serious challenges of mental wellness

- Review funding formulas for transfer payments to provinces and territories and make the structural changes necessary to ensure that resources are directed towards maximizing impactful results and policy innovation to Arctic citizens and communities

Concluding remarks

At the beginning of this report, I explained that during this assignment I was searching for insights into two overarching questions:

- Why, in spite of substantive progress over the past 40 years, including remarkable achievements such as land claims agreements, Constitutional inclusion and precedent-setting court rulings, does the Arctic continue to exhibit among the worst national social indicators for basic wellness?

- Why, with all these hard-earned tools of empowerment, do many individuals and families not feel empowered and healthy?

There are no simple answers to either of these questions. Yet, in my travels I saw flashes of where answers lie. I heard it in the voices of youth, repeated by some leaders, who spoke about the importance of a culturally-relevant education being a path to self-worth and opportunity. I heard it in the voices of people who are champions of Indigenous languages, and the affirming effect languages have for the health of our communities. I saw examples of where strong, local leadership can transform communities, addressing the issues of community wellness, one conversation, one meeting, one collaboration, at a time. There is an incoming generation of young ‘champions' that we need to recognize, believe in and support. I also saw the evolving nature of elected leadership in my travels where historic silos were being broken down to cross divides and get things done. I was encouraged to see examples of leadership getting past the outdated and unhelpful idea that we can't be critical of our own actions.

As I noted earlier, this assignment gave me the opportunity to reflect on the road travelled since 1982 and what progress has been made under the far-reaching obligations of Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. There are links between rights for Aboriginal peoples embodied in our Constitution, and a vision for a sustainable Arctic. It is why I embedded "Understanding and honouring Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982" as one of the core ‘principles of partnership.'

It is noteworthy that there have been a number of other signposts along the road from the Constitution Act, 1982: Canada's ratification of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; the commitment to implement the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action; and, the public inquiry and appointment of the Commissioners on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. These advances must become both roots and branches in a new Arctic Policy Framework. In my lifetime, the energies of leadership were focused on securing rights and creating mechanisms of governance and resource-sharing, and the body of work is impressive. It is time now to focus this legacy of leadership on our people's health in the broadest sense of the word.

This will require leadership. These past months have reminded me that we sometimes think too narrowly about what leadership is; it does not rest solely with elected leaders, although this is essential. Leadership is also found in the actions of bureaucrats, negotiators, policy and program specialists, in the actions of local champions and in the voices of advocates. In other words, we all share a role, if not an obligation, when developing and implementing Arctic policy of demonstrating a measure of leadership and understanding the history and evolution of ‘the honour of the Crown.'

On the second question, as to why do many individuals and families in Arctic communities not feel empowered and healthy, I believe that answers will be found in programs, processes, and policies that enable Arctic leaders to craft and support their own community-based and community-driven solutions. It is evident that a successful model of program delivery is ensuring organizational and leadership capacity is developed, nurtured and adequately supported. Growth and development of the Arctic will not be ‘found' in a new Arctic Policy Framework but rather ‘enabled' by policies built on partnership, respect and reconciliation.

Before I conclude, I want to elevate one final topic that rarely finds its way to the top of the list in policy setting agendas, but simply must. In my brief mandate, I could do little more than listen with a heavy heart when people spoke to me about the frightening scope of mental health problems in our communities. I heard, as I have for many years, the plea for national action to tackle the mental health crisis in our communities that manifests in drug and alcohol dependency, family violence and is driving our youth to increasing rates of suicide.

The stark reality of how widespread the mental health crisis is hits me deep down every time I hear that there has been another suicide, which happens all too frequently. I think to myself, there must be something I can do to get the help individuals need when they are ready to start the process of healing, which in many cases takes a long time. They need a strong support system that includes services from prevention to diagnosis to treatment, and counselling and trained Indigenous staff throughout the continuum of services. Non-Indigenous professionals also require specific training in cultural competency. So, I implore you and your fellow Ministers to work with territorial and provincial governments and Indigenous organizations to establish a coordinated set of actions and provide needed resources.

Committing to "greater action to address the serious challenges of mental wellness" was the fifth aspect of the Joint Statement Commitments by President Obama and Prime Minister Trudeau. Where appropriate, I have inserted recommendations related to mental health in a number of the themes covered in my report. It is my sincere hope that this topic will not be lost in priority-setting and policy-making actions in the days ahead.

My advice to you in this report reflects the full range of discussions I held in the Arctic and the submissions received. I trust that you will act on this advice as you work towards a new Arctic Policy Framework with northern governments and Indigenous leaders.

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of recommendations

1 Education

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Make education the cornerstone of the Arctic Policy Framework as the key to healthy people and social and economic progress

- Increase funding for quality, culturally-relevant Early Childhood Education (e.g. Aboriginal Head Start)

- Announce its intent to create a University of the Arctic by striking a representative Arctic University Task Force to create a vision and business case

- Increase access to a continuum of community-based mental health services for students

- Invest in closing the "digital divide" in order to increase access to online learning and research for Arctic students

- Maintain and expand its support for Sivuniksavut programs in Inuit Nunangat

- Commit to supporting Indigenous languages by working with governments across their programs, school boards and Indigenous organizations with specific mandates for language preservation and revitalization to determine where their needs are and where policy and financial support will provide the most benefit

- Require that all federal investments in infrastructure and housing include skills training, apprenticeships and employment

2 Research and Indigenous knowledge

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Establish and support a Centre for Indigenous and Local Knowledge as a core element of the Canadian High Arctic Research Station to link to and support regional cultural institutes and programs

- Direct Polar Knowledge Canada to include the theme of improving the health and wellness of families (physical and mental health, housing, food security etc.) in its research priorities

- Ensure appointments to the Polar Knowledge Board are inclusive and representative of Arctic peoples and that priority-setting exercises are informed by representative input from Arctic peoples, governments and Indigenous organizations

- Invest in the hydrographic data collection necessary to establish low-impact Arctic marine shipping corridors

- Partner directly with Indigenous organizations and territorial governments to create vessel management and monitoring programs to ensure increased ship traffic benefits Arctic communities

- Increase the level of geoscience spending in the Arctic to expand the availability of baseline mapping and geological research

3 Infrastructure policy

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- With Arctic governments and Indigenous leaders, develop criteria for Arctic infrastructure projects that reflect the singularly unique context for infrastructure spending, the ‘catching up' nature of the infrastructure gap in the Arctic, and that corrects for the punitive nature of per capita allocations without base funding

4 Broadband

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Commit to a goal of service parity in broadband by investing in the recommendations found in the 2011 Arctic Communications Infrastructure Assessment Report along with the 2016 Arctic Economic Council (AEC) report Arctic Broadband: Recommendations for an Interconnected Arctic

- Revise its infrastructure program criteria to allow for Arctic broadband to be considered a project of ‘national infrastructure' under the Building Canada Fund

- Build digital infrastructure and programming into any federal initiatives in education, language and mental health support

5 Housing

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Act on the recommendations of the findings of the Senate Standing Committee Report on Housing in Inuit Nunangat and work with governments and indigenous organizations to adapt those recommendations to the other Arctic regions covered by my mandate (which includes the three territories in addition to the Inuit regions of Quebec and Labrador)

- Design and implement multi-year funding agreements compatible with planning, transportation and construction realities in the Arctic

- Adjust policies of northern housing authorities to allow for ways to involve Indigenous peoples in the conceptualization, design, construction, and maintenance of housing in their communities

- Under social infrastructure funds, establish a program to encourage construction of housing for people living with mental illness under a model of community-based support and treatment

6 Reducing fossil fuel dependence

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Ensure that the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada-led process announced in December 2016 involve Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations

- Establish a business development fund for Indigenous-led renewable energy and efficiency projects

-

Expand and collaborate with the Yukon College and the new Industrial Research Chair for Colleges in Northern Energy Innovation. This NSERC-funded position is further supported by Yukon Energy, ATCO Electric, the NWT Power Corporation and Qulliq Energy. The research will focus on the integration of renewable energy in isolated community grids, energy storage, diesel efficiencies, independent energy valuation, residential and utility partnership, and demand side management

7 Toward a new, ambitious Arctic conservation goal

Immediate steps towards meeting existing conservation targets

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Expedite the process of completing Tallurutiup TariungaFootnote 4 (Lancaster Sound) as a National Marine Conservation Area using the expanded boundary set out by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association

- Expedite the process of completing Thaidene Nene as a National Park

- Accept the Pikialasorsuaq Commission's recommendation for the creation of an Inuit-led management plan and monitoring process for the entire North Water Polynya and consider recognizing the region as an Indigenous Protected Area

- Develop a "whole of government" approach to terrestrial and marine park-related impact benefit agreements that meets or exceeds best global standards

Indigenous protected areas: Toward a new, ambitious Arctic conservation goal

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Work to formally recognize existing land and marine conservation planning designations as the basis for setting and realizing a new, ambitious conservation goal

- Continue progress toward becoming the first country in the world to have a legal mechanism to recognize Indigenous protected areas

- Work with Arctic governments and Indigenous organizations to conceive a new federal policy directive that sets out a process for the identification, funding and management of indigenous protected areas

- Identify long-term stable funding to support locally-driven terrestrial guardians and Arctic coastal and marine stewardship programs

- Make a request to the International Union on the Conservation of Nature to formally recognize Indigenous protected areas as a valid conservation designation under the "other acceptable conservation measure" category

8 Developing a new Arctic Policy Framework

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Convene a summit of northern Premiers and Indigenous leaders with the Prime Minister and key Ministers to discuss a process for developing a new Arctic Policy Framework

- Develop, with Arctic leaders, principles of partnership for policy processes

- Commit to greater action to address the serious challenges of mental wellness

- Review funding formulas for transfer payments to provinces and territories and make the structural changes necessary to ensure that resources are directed towards maximizing impactful results and policy innovation to Arctic citizens and communities

9 Addressing the mental health crisis

It is recommended that the Government of Canada:

- Work with territories, provinces and Indigenous organizations to establish the baseline data necessary to identify the gaps in mental health services

- With territories, provinces and Indigenous organizations develop a national strategy and implementation plan including investments that will be required to close gaps in mental health services (prevention, diagnostic, counselling and treatment)

- Provide sustained funding for training programs to increase Indigenous mental health professionals, and training in cultural competency for non-Indigenous professionals

Appendix 2: Map of land and marine planning conservation areas in northern Canada

Text description of the map of land and marine planning conservation areas in northern Canada

Map shows existing marine protections highlighted:

- along the shorelines west and south of Alert

- west of Tuktoyaktuk

- west and northwest of Ikaahuk

- in a region located north of Paulatuk

- northeast of Umingmaktuk

- southeast of Ausuittuq

- areas south and northwest of Qausuittuq

- a region southeast of Ausuittuq

- around the island north of Mittimatalik