Summative Evaluation of the Education Facilities and Other Community Infrastructure Sub Programs (Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program)

June 2015

Project Number: 1570-7/14090

PDF Version (492 KB, 50 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program Description

- 3. Evaluation Methodology

- 4. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

- 5. Evaluation Findings – Performance

- 6. Evaluation Findings – Design and Delivery

- 7. Findings – Efficiency and Economy

- 8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Reference List

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| ACRS |

Asset Condition Reporting System |

| CFMP |

Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| ICMS |

Integrated Capital Management System |

| P3 |

Public/Private Partnership |

| O&M |

Operations and Maintenance |

Executive Summary

Through its Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program (CFMP), Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) provides funds for the planning, construction/acquisition, and operation and maintenance of First Nation community infrastructure. The Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program has four sub-programs: Water and Wastewater Facilities, Education Facilities, Housing, and Other Community Infrastructure.

Including Economic Action Plan funds delivered through CFMP, $5.8 billion was spent in the five year period evaluated (2009-10 to 2013-14). Of this total, $3.3 billion was spent by the Education Facilities and Other Community Infrastructure sub-programs, the two sub-programs covered by this evaluation.

Although the infrastructure deficit continues to be large (as is the case for all municipalities), some of the most critical infrastructure gaps, in particular in education, have been addressed on-reserve. As well, AANDC, in partnership with First Nations, has been exploring ways to make new construction projects more cost-effective and to maximize limited federal funds through leveraging.

That said, there continues to be challenges, and AANDC fell short of its expected outcomes for both sub-programs. Infrastructure in First Nation communities deteriorates more quickly than in nearby off-reserve communities. If the Department and First Nations are to fully address First Nation communities' infrastructure needs, more attention is necessary in two key areas. One is building codes and standards; the other is maintenance.

For major and minor capital projects, there must be adherence to federal and provincial building codes and standards to ensure that First Nations and the federal government get value for capital investments. Evaluation evidence suggests that construction projects have sometimes failed to meet these standards. As a result, buildings may not be lasting their full expected lifespan.

Maintenance gaps and weaknesses are also contributing to a shortened infrastructure lifespan. For example, evaluators found exposed wiring, building mold, and fire alarms and fire trucks that did not function properly. Reasons varied between communities, but the list includes: vandalism, lack of own-source revenues to cover First Nations' share of maintenance budgets, use of AANDC maintenance funds for other purposes in First Nation communities, overuse/ overcrowding of buildings and, possibly, lack of capacity in First Nation communities to address maintenance issues proactively.

There are tools already in place to address many of these weaknesses — certified completion certificates for new construction and renovation projects, the requirement for annual First Nation Maintenance Management Plans, and Asset Condition Reporting System inspection reports — but they seem not to be fully utilized at this time.

Based on these findings, the following recommendations were developed in order to strengthen CFMP delivery and improve CFMP performance by addressing these areas for improvement.

It is recommended that AANDC:

- Implements a regular compliance audit for major capital projects to ensure that certificates of completion are received, signed by a certified technical expert as well as the band chief or his/her designate as required, which confirm that all applicable federal and provincial codes/standards have been met.

- Encourages First Nations to include requirements in their procurement documents regarding asset documentation to be delivered by contractors as part of contracts for capital projects, in part to support proactive maintenance and to secure appropriate, affordable insurance.

- Ensures that annual First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans reflect and take into account deficiencies identified through the most recent Asset Condition Reporting System reports, in order to address them.

- Ensures that strategies to discourage and prevent vandalism are reflected in guidance to First Nations on procurement and maintenance management.

- Formulates clear and specific criteria for the Asset Condition Reporting System General Condition Ratings to ensure consistency and comparability in the assessment of each asset. Explore the need to evaluate the contracted resources that perform this important work.

- Considers how to build First Nations' capacity to maintain community infrastructure by extending the School Maintenance Training Program to other parts of the country and establish a comparable training program for First Nation staff responsible for the maintenance of Other Community Infrastructure, especially fire prevention infrastructure.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of Education Facilities and Other Community Infrastructure (Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program)

Project #: 1570-7/14090

Note to Reader:

The Department has addressed all recommendations in the report and has fully implemented the Management Response and Action Plan. In addition, since the report, Budget 2016 is investing $969.4 million over five years in First Nation education infrastructure, for the construction, repair and maintenance of First Nations schools.

1. Management Response

The Program has reviewed and agrees to address the below recommendations.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title/Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

Program Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Implement a regular compliance audit for major capital projects to ensure that certificates of completion are received, signed by a certified technical expert as well as the band chief or his/her designate as required, which confirm that all applicable federal and provincial codes/standards have been met. | The program accepts this recommendation. Implement a regional compliance audit to ensure that certificates of completion, signed by a certified technical expert as well as the band chief or his/her designate, are received and confirm all applicable federal and provincial codes/standards have been met as required by the terms and conditions of the recipient funding arrangements. |

Senior Director, Strategic Policy, Planning and Innovation Directorate with support from Audit and Evaluation | By end of Q4 2015-2016 Revised completion date: January 2017 |

Status: Underway A Compliance Regime is currently being developed in relation to the new Program Control Framework. This regime is expected to be completed by the end of Q3 2016-17. Compliance audits will resume following the completion of the Compliance Regime. AES: Recommend to close. Closed. |

| 2. Encourage First Nations to include requirements in their procurement documents regarding asset documentation to be delivered by contractors as part of contracts for capital projects, in part to support proactive maintenance and to secure appropriate, affordable insurance. | The program accepts this recommendation. Revise the Protocol for AANDC-Funded Infrastructure, which is referenced in all contribution agreements that include funding from the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program, to indicate that First Nations should require contractors to provide pertinent documentation as part of the deliverables of their capital projects. |

Senior Director, Program Design and Partnership Directorate | Q4 2015-2016, for use in 2016-2017 |

Status: Request to Close (Completed) As a condition for funding, First Nations must comply with the PIFI (was PAFI before), which includes provisions to comply with INAC Tendering Policy and Construction Contracting Guidelines for First Nations and Aboriginal Communities documents. The Construction Contracting Guidelines for First Nations and Aboriginal Communities documents provide capital project contracting guidelines, which include as a standard practice getting and recording pertinent project delivery documents, including asset documentation to be delivered, and securing appropriate insurance. INAC regional officers provide support to First Nations as needed in that respect. AES: Recommend to close. Closed. |

| 3. Ensure that annual First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans reflect and take into account deficiencies identified through the most recent Asset Condition Reporting System reports, in order to address them. | The program accepts this recommendation. Relevant Asset Reporting Condition System health and safety deficiencies will be linked to the First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan in AANDC's Integrated Capital Management System. |

Senior Director, Program Design and Partnership Directorate | Q4 2015-2016, for use in 2016-2017 |

Status: Request to Close (Completed) Asset Condition Reporting System (ACRS) deficiencies now linked in the Integrated Capital Management System and included in the call package to First Nations requesting their input to the First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan. This is done so that deficiencies identified in the ACRS inspection reports can be addressed via the Investment Plan. AES: Recommend to close. Closed. |

| 4. Ensure that strategies to discourage and prevent vandalism are reflected in guidance to First Nations on procurement and maintenance management. | The program accepts this recommendation. Revise the Protocol for AANDC-Funded Infrastructure, and related guidance on maintenance management provided in the Protocol for AANDC-Funded Infrastructure, to encourage First Nations to use strategies aimed at minimizing the impacts of vandalism. |

Senior Director, Program Design and Partnership Directorate | Q4 in 2015-2016, for use in 2016-2017 |

Status: Underway In consultation with regional offices and a third party expert in the field, the Community Infrastructure Branch has produced a revised draft tendering policy, a draft policy framework, and new draft procurement guidance documents (i.e., a procurement management manual, a construction project management manual, a project risk management manual, and a tendering policy training manual and road map). These documents will include recommendations to use durable material, not only to mitigate the impacts of vandalism, but also to be resistant to other impacts such as climatic conditions, to ensure that funded assets meet their expected service life. With regard to maintenance management, the Community Infrastructure Branch has published a Maintenance Management Planning (MMP) guide, which provides First Nations with a systematic methodology to track and fix infrastructure deficiencies, including those due to vandalism. The guide already published is on water and wastewater, and a similar MMP for buildings is pending approval and publication. Lastly, in 2015-2016, CIB has created a formal link into the FNIIP DCI process, to bring ACRS inspection deficiencies to the attention of First Nations, to ensure that known deficiencies, including those due to vandalism, get addressed as part of scheduled annual infrastructure maintenance and repair projects. AES: Recommend to close. Closed. |

| 5. Formulate clear and specific criteria for the Asset Condition Reporting System General Condition Ratings to ensure consistency and comparability in the assessment of each asset. Explore the need to evaluate the contracted resources that perform this important work. | The program accepts this recommendation. Add instructions to the Asset Condition Reporting System questionnaire on how to use the existing condition rating categories "1" (poor) to "9" (good). |

Senior Director, Program Design and Partnership Directorate | Q4 in 2015-2016, for use in 2016-2017 |

Status: Request to Close (Completed) The ACRS questionnaire, embedded into ICMS and available to inspectors in the field, lists for each building sub-component (exterior, roof, etc) specifically what needs to be verified and be factored into the various grades of Good, Fair, and Poor condition. This information is used for two purposes: 1) inform annual maintenance plans to act on ACRS findings and 2) be used as INAC program performance indicators. Regarding item 1), ACRS findings are further supported with a list of deficiencies to be addressed, and the ACRS system offers the inspector to further associated condition ratings (e.g. minor, major, replacement, etc) as well as the type (health & safety, operational, etc) and the level of urgency (immediate or future) to inform maintenance action plans. Each year, INAC communicates those findings to First Nations for action and inclusion in their annual investment plans (FNIIP). For Health and Safety deficiencies, a special tab in the FNIIP process has been added in 2015-2016, so that First Nations have this information handy while creating their annual investment plans. Regarding item 2) Performance reporting does not differentiate between intermediate levels of Good, Fair or Poor, and therefore this has no impact on performance reporting. Lastly, ACRS inspections are contracted out annually to technical experts who must use their professional judgement in their ratings. The ACRS system in place offers them the flexibility to apply that judgement, and the tools they need to further identify and qualify remediation actions needed, as described above. AES: Recommend to close. Closed. |

| 6. Consider how to build First Nations' capacity to maintain community infrastructure by extending the School Maintenance Training Program to other parts of the country and establish a comparable training program for First Nation staff responsible for the maintenance of Other Community Infrastructure, especially fire prevention infrastructure. | The program accepts this recommendation. Expand the existing Circuit Rider Training Program, currently focused mainly on the water and wastewater asset category, to the schools and housing asset categories. |

Senior Director, Program Design and Partnership Directorate | Minimum Guidelines requirements developed by Q3 in 2015-2016 Program available nationally in 2015-2016 | Status: Underway Minimum guidelines were developed and shared with the Circuit Rider Training Program Association for feedback in January 2016. These minimum guidelines will form the basis of requests for proposals to deliver this new capacity development program in 2016-17. AES: Recommend to close. Closed. |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on June 19, 2015, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed on June 25, 2015, by:

Scott Stevenson

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations Sector

1. Introduction

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada's (AANDC) Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program (CFMP) is the main pillar of Government of Canada support for First Nation community infrastructure. It provides funding to First Nations communities for the acquisition, construction, operation, and maintenance community infrastructure and facilities. This report presents findings of a summative evaluation of two of four CFMP sub-programs.

1.1 Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the Education Facilities and the Other Community Infrastructure sub-programs.Footnote 1 The evaluation was conducted in compliance with the 2009 Treasury Board Secretariat Policy on Evaluation. It covers the five years from 2009-10 to 2013-14. Field work and analysis was conducted between September 2014 and April 2015.

1.2 Project Management and Quality Assurance

Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved in June 2014 by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee and the Committee also reviewed this evaluation report and approved the Management Response and Action Plan. The Committee Chair is the AANDC Deputy Minister and the other members are the Chief Financial Officer, senior assistant deputy ministers, and external experts.

The evaluation process was guided by an Evaluation Working Group that reviewed and validated the methodology, preliminary findings, and the draft final report. The Evaluation Working Group included members of the Assembly of First Nations and a number of other First Nations organizations.

The draft evaluation report also underwent a peer review process in the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB).

2. Program Description

The Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program falls under Section 3.4 of AANDC's Program Activity Architecture: Infrastructure and Capacity, which is part of Land and Economy programming.

Through CFMP, funding is provided to First Nations on-reserve and to First Nations and other eligible recipients on Crown land or recognized Indian land. Program activities are governed by the terms and conditions of the Contributions to support the construction and maintenance of community infrastructure Transfer Payment Program Authority.

Through CFMP, the Department supports costs of planning, construction or acquisition, and operation and maintenance of First Nation community infrastructure. More specifically, the program assists First Nations to acquire, construct and operate, and maintain housing and community infrastructure, including water and wastewater systems, schools, roads and bridges, electrification, and community buildings; to sustain community infrastructure, including solid waste management; energy systems; local roads and bridges; connectivity; and planning and skills development or activities to raise the level of fire protection awareness.

AANDC allocates funding for the construction and the maintenance of community infrastructure to First Nations at regional level through formula, proposal based project funding or as a combination of both. The CFMP budget is divided into:

Formula-based funding, which includes:

- Operations and Maintenance (O&M): for the operation and maintenance of existing community infrastructure assets. The level of funding provided to the First Nation varies from 20 percent to 100 percent depending on the type of asset.

- Minor Capital: for housing and for acquisition, construction, renovation, or repair projects valued below $1.5 million.

Proposal-based funding, which includes:

- Minor Capital: for housing and for acquisition, construction, renovation, or repair projects valued below $1.5 million.

- Major Capital: for specific construction, acquisition, renovation, or significant repair projects valued above $1.5 million.

Major capital projects are funded primarily by targeted initiatives such as: funding announced by the Government of Canada for education facilities as part of the Economic Action Plan 2012, the continuation of the First Nation Infrastructure Fund announced in Economic Action Plan 2013, and the extension of the First Nations Water and Wastewater Action Plan announced in Economic Action Plan 2014.

During the period under review, formula-based funding averaged 53 percent of total CFMP spending and proposal-based funding averaged 47 percent (Table 1).

| Formula | Minor Capital Proposal-Based | 176,291,290.47 | 16% | 53% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation & Maintenance | 419,576,581.03 | 37% | ||

| Proposal | Proposal-Based Capital | 529,773,934.86 | 47% | 47% |

| Total: | 1,125,641,806.36 | 100% | 100% | |

To guide decision making, the Department has established four overarching priorities for its CFMP spending:

- Mitigating health and safety risks;

- Protecting and maintaining the life cycles of existing assets, emphasizing health and safety;

- Addressing backlogs of water and sewage program activities; and

- Investing in sustainable communities (housing, electrification, roads, educational and community facilities, etc).

A National Priority Ranking Framework has been developed to ensure that capital funding decisions are consistent and transparent. The framework ranks projects according to the following priorities, in order of weight:

- Protection of health and safety of assets (assets require upgrading or replacement to meet appropriate standards);

- Health and safety improvements (upgrades of existing assets, new construction/acquisition projects to mitigate an identified significant risk to health and safety);

- Recapitalization/major maintenance (to extend the useful operating life of a facility or asset, or maintain the original service level of the asset); and

- Growth (anticipated community growth requiring new housing, roads, schools, community buildings, etc) (AANDC 2015).

Starting in 2011-2012, Education Facilities projects over $1.5 million, including both new construction and renovations/additions, have been ranked according to the National Priority Ranking Framework and the School Priority Ranking Framework (School Facilities Progress Report, 2006-2012, 5-6). Funding is then provided based upon the School Space Accommodation Standards guidelines (AANDC 2013g, 3). The School Priority Ranking Framework applies a point-ranking system based on nationally-established criteria, using the following five categories:

- Condition of Existing Facility (focus on health and safety);

- Overcrowding (gross school area);

- Accessibility to off-reserve school;

- Design (grade distribution and amenities offered); and

- Cost efficiency opportunities (external funding sources and aggregation).

2.1 Goals and Expected Outcomes

At the request of CFMP Program management, the evaluation used the program's 2009 Performance Measurement Strategy to measure outcomes achievement.

The Performance Measurement Strategy defines the program's goal as follows: to support First Nations communities in building a base of infrastructure (i.e., water and wastewater facilities, education facilities, housing, and other community infrastructure) that protects health and safety and enables engagement in the economy (AANDC 2009).

The program's logic model defines immediate and intermediate expected outcomes for each of the program's sub-programs. For both the Education Facilities and Other Community Infrastructure sub-programs, the immediate expected outcomes are:

- Infrastructure meets applicable standards;

- Infrastructure meets the needs of First Nation communities; and

- First Nation communities have capacity to maintain infrastructure.

Intermediate expected outcomes differ between the two sub-programs. For the Education Facilities sub-program, the expected intermediate outcome is: First Nation communities have a base of education facilities that meets established standards. For the Other Community Infrastructure sub-program, the expected intermediate outcome is: First Nation communities have a base of safe community infrastructure (e.g. fire protection, electricity, safe roads and bridges, and telecommunications) that meets established standards.

2.2 Other Community Infrastructure

Through the Other Community Infrastructure sub-program, AANDC provides advisory assistance and funding for the planning, design, construction/acquisition of community infrastructure assets for First Nation communities. It also funds renovation, operation and maintenance, training and capacity-building activities related to community infrastructure assets and facilities.

Community infrastructure assets, systems and projects can include:

- Community buildings;

- Community solid waste collection and disposal systems;

- Electrical and energy systems;

- Connectivity;

- Terrestrial transport infrastructure (related to connectivity infrastructure, such as fibre cables or copper-based pole lines);

- Bulk fuel storage and distribution systems;

- Roads, including community roads, access roads, bridges and other transportation and access;

- Fire-fighting facilities and fire detection systems, vehicles and equipment;

- Community buildings, facilities and equipment, including construction/maintenance equipment;

- Furniture and office equipment; and

- Structural mitigation projects for flood and erosion control.

There were four AANDC priorities: fire safety, school safety, connectivity, and energy/electrical systems.

2.3 Education Facilities

Through the Education Facilities sub-program, AANDC provides advisory assistance and funding for:

- Planning, design, construction/acquisition, renovation/repair, replacement, and operation and maintenance of band-operated elementary and secondary education facilities (school buildings, teacherages, student residences) and related services;

- Acquisition, replacement, and repair of furniture, equipment and furnishings for schools, teacherages, and student residences; the identification of education facility needs and development of education facility plans; and the design and ongoing implementation of maintenance management plans; and

- Agreements with provincial school boards for the planning, design, construction/acquisition of facilities for the elementary and secondary education of First Nation children.

2.4 CFMP Resources

For the five-year period covered by this evaluation, the program's resources averaged $1.2 billion per year, a total of $5.8 billion over five years (Table 1).

| Sub-Program | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water and Wastewater | 380.3 | 395.0 | 311.0 | 302.5 | 295.1 | 1,683.8 |

| Education Facilities | 277.2 | 303.8 | 201.3 | 225.6 | 214.2 | 1,222.1 |

| Housing | 199.8 | 191.4 | 132.3 | 120.7 | 143.1 | 787.0 |

| Other Community Infrastructure | 433.0 | 406.5 | 448.4 | 420.9 | 382.6 | 2,091.4 |

| Total | 1,290.2 | 1,296.6 | 1,092.9 | 1,069.4 | 1,035.0 | 5,784.2 |

Source: Chief Financial Officer, AANDC

Additional federal funding for First Nations infrastructure, for example, special Economic Action Plan allocations was also delivered through AANDC's Community Facilities and Maintenance Program.

In 2014, the Government of Canada committed $500 million dollars over seven years for a new Education Infrastructure Fund (Department of Finance 2014). This investment builds upon the three-year, $175 million federal investment in school infrastructure that was announced in Economic Action Plan 2012.

2.5 The Funding Process

Major and Minor Capital Projects

Every year, regional offices work with First Nations to develop five-year capital plans (First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans) that identify their major and minor capital infrastructure priorities, including education facilities (AANDC 2014c). Some First Nations also develop Comprehensive Community Plans, outlining long-term community priorities for their communities, the federal government, and investors; First Nations Infrastructure Fund has been particularly successful in supporting First Nations development of Comprehensive Community Plans (AANDC 2014d).

Completed First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans are submitted to AANDC regional offices. Regional offices then produce regional First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans, guided by the National Priority Funding Evaluation and Measurement Matrix. Regional First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans are submitted to AANDC's Headquarters. Projects that mitigate the most urgent health and safety risks are ranked as highest priority.

AANDC Headquarters then develops a National First Nations Infrastructure Plan focusing federal resources on areas of highest need nationally. First Nations with projects on the National First Nations Infrastructure Plan are invited to prepare funding proposals for submission to regional offices.

In fact, funding applications are submitted at each project stage (feasibility, pre-design/design, construction/acquisition). Progress payments and final payments may be tied to the achievement of pre-determined performance expectations.

The amount of CFMP funding is based on a national formula or project proposal, or a combination of the two. The funding arrangement chosen depends on the demonstrated capacity of the recipient to manage transfer payments. Besides standard contribution funding arrangements, the Department can use flexible or block contribution funding arrangements.

CFMP funding is provided by means of AANDC-First Nations contribution agreements, which set out standards and codes to be met and reports/certificates to be provided by recipient First Nations. Alternatively, recipients may be given advance payments based on a cash-flow forecast subject to the achievement of pre-determined performance expectations.

Operations and Maintenance

In addition to funding major and minor capital infrastructure projects, CFMP devotes approximately 1/3 of its budget to funding the operation and maintenance of community infrastructure and assets that have been built and/or renovated with federal government funds. Proper operation and maintenance of community infrastructure is critical to protecting the health and safety of community members and ensuring that buildings and other assets live out their full lifespan.

Every First Nation is required to produce a Maintenance Management Plan, approved by the First Nation Council, which describes how the First Nation will operate and maintain its community infrastructure, housing and assets (AANDC 2014e, §5.0). The Maintenance Management Plan is approved by the nation's Council and made available to the Department. Maintenance Management Plans are expected to include:

- An up-to-date inventory of all infrastructure and housing assets for which AANDC provides O&M funds;

- The maintenance activities and the frequency with which such activities will be conducted for each asset;

- An estimate or the most recent three-year average total annual cost of operating and maintaining all community infrastructure and housing assets for which a funding subsidy is to be provided by AANDC;

- Measures to ensure that satisfactorily trained personnel are available at all times to operate and maintain technical systems according to the design standards of the specific facility or asset (e.g., for water and wastewater treatment plants, operators should be certified to the level of the plant);

- The provision of fire protection services; and

- Data to update the Department's Integrated Capital Management System (ICMS).

The amount of AANDC's operation and maintenance funding is based on a formula. Assets intended for common use and related to essential services (e.g., band -operated schools and fire halls) receive a 100 percent subsidy; assets providing services to specific users where user fees can be collected (e.g., water/sewage treatment plans and landfills) receive a 80 percent subsidy; and assets not directly affecting the physical health of community members (e.g., band offices and community halls) receive a 20 percent subsidy. These figures may be adjusted to take account of community remoteness, base unit operating costs, and other factors.

First Nations are expected to contribute to the cost of operating and maintaining all AANDC-funded infrastructures, except schools and fire halls.

Unlike capital funding, operations and maintenance funding is provided without condition; its use is at the discretion of each community's Chief and Council. The Department does not receive reports on how departmental operations and maintenance funding is used or the extent to which First Nations contribute to the costs of operations and maintenance.

2.6 Integrated Capital Management System and Asset Condition Reporting System

The Department uses the ICMS’ Inspection and Asset modules, to collect and record data on the condition of on-reserve assets via the Asset Condition Reporting System (ACRS) inspections. The condition of each asset (i.e., piece of infrastructure on-reserve) is assessed every three years, according to the ACRS inspection cycle.

ICMS is used to map O&M funding to First Nations assets supported by the Department. It contains base-level information on capital assets (location of asset, asset type, asset quantity, etc), housing information (basic community services, housing conditions, water quality and sewer services), and the result of cyclical asset inspections. ICMS also holds site-level information on school facilities and capital plans.

ICMS is intended to be a tool for managers responsible for the operations, maintenance and construction of capital assets, engineering and costing personnel, personnel responsible for the inventory data collection and maintenance for the system, and tribal councils and First Nations to verify allocations, asset quality, conditions, and needs. Because ICMS information is meant to be used as a planning tool, a summary is provided annually to AANDC Headquarters, AANDC regional offices, First Nations, and tribal councils.

2.7 Codes and Standards

In October 2014, AANDC developed a Protocol for AANDC-Funded Infrastructure to guide First Nations and contractors in the safe construction and maintenance of federally-funded infrastructure on-reserve.

The Protocol consolidates mandatory statutes and regulations into a single living document for ease of reference; it lists policies, codes, directives, standards, protocols, specifications, guidelines and procedures, including annexes for each province/territory, where additional protocols apply. AANDC requires that CFMP First Nations funding recipients (and contractors working for them) adhere to the regulations and processes outlined in the Protocol (AANDC 2014e, §1.1-1.5).

Within 90 days of each building project's completion, reporting is expecting to include a certificate of completion signed by a certified professional that attests that the structure has been built to codes and standards, a legal survey and, as-built drawings.

2.8 Roles and Responsibilities

First Nation communities own and operate community infrastructure facilities and systems on-reserve and are responsible for maintaining existing assets and building new ones (AANDC 2014e, §1.2). AANDC regional offices assist First Nations in developing First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans, managing capital projects, and operating and maintaining existing assets. The Council of a First Nation is expected to ensure that applicable codes and standards are met. Qualified professionals hired by a First Nation are expected to familiarize themselves with and abide by applicable standards and requirements (AANDC 2014e, §1.1).

AANDC regional offices set regional infrastructure investment priorities, in keeping with national criteria, advise First Nations on capital planning, allocate regional CFMP budgets for maintenance and most capital projects, approve and manage capital funding arrangements, and monitor First Nations' capital management activities. Regional offices have engineers and other employees who are available to provide guidance to First Nations and third-party contractors regarding compliance with the policies and codes. With the exception of Alberta, whose ACRS inspections are performed by the Technical Services Advisory Group, regional offices also contract engineering firms to perform cyclical ACRS inspections.

AANDC Community Infrastructure Branch is responsible for developing and maintaining overall policy for the allocation of resources to regions, as well as the development of national criteria, policies, procedures and directives for program delivery for all four sub-programs. The Community Infrastructure Branch oversees regional offices, supports regions in developing their regional First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans, establishes reporting requirements and manages program data and performance measurement.

AANDC Operations Committee provides a high-level overview of the First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans and strategic direction on capital investment priorities. The Committee also oversees implementation of the National First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan and makes recommendations on funding requests for capital projects that are deemed high risk or cost more than $10 million.

3. Evaluation Methodology

3.1 Lines of Evidence

Evaluation findings, conclusions and recommendations are based on the following six lines of evidence:

Document Review

Evaluators reviewed departmental documents (past evaluations, audits, management responses and action plans, etc) and many other federal and regional documents (Budget documents, action plans, publications, recommendations of the National Aboriginal Economic Development Board, testimony before the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples study on challenges relating to First Nations infrastructure on-reserves, including testimony from such Aboriginal organizations as the Assembly of First Nations, the British Columbia Aboriginal Child Care Society, First Nations of Alberta Technical Services Advisory Group, and Turtle Island Associates Inc.).

Literature Review

A literature review examined trends, challenges, and best practices related to infrastructure development and financing for First Nations in Canada and Aboriginal communities abroad. The literature included policy papers by independent think-tanks, peer-reviewed Canadian and international publications, reports by international organizations (e.g., the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the United Nations) and Canadian media.

Database Review

Evaluators looked at the Integrated Capital Management System database for fiscal years 2009-10 to 2013-2014 to analyze its Asset Condition Reporting System inspection results. The purpose of the analysis was twofold: to plot the condition of the assets and observe the regional, zonal variations in the condition and estimated remaining life of assets, and to understand CFMP spending on infrastructure.

According to the ACRS database, since 2009, a total of 20,168 ACRS inspections have been done of assets funded by the sub-programs under review (Education Facilities and Other Community Infrastructure). For purposes of this report, three ACRS inspection variables were reviewed: General Condition Rating description, General Condition Rating scores, and Estimated Remaining Life.Footnote 2

A review of financial data looked at actual spending for education facilities and other community infrastructure by region. To the extent possible, expenditures were broken down by type and source of funding.

Key Informant Interviews

To augment evaluators' understanding of the CFMP sub-programs and their delivery, 23 semi-structured interviews were conducted in person or by telephone with individuals with direct experience and knowledge of education facilities and/or other community infrastructure in First Nations communities. Five AANDC Headquarters staff, 12 AANDC regional staff, and six representatives of First Nation and Aboriginal organizations were interviewed.

Review of Planning and Priority Setting Processes for Education Infrastructure

A comparison of capital education facilities prioritization processes in different Canadian jurisdictions was also done. The capital funding practices for each Canadian province and school boards/districts in the largest cities of each province (Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, Moncton, Halifax, Charlottetown, St. John's) were examined. As well, the websites of each provincial Ministry of Education and school board/district was reviewed.

Three provinces (Alberta, Ontario, Manitoba) and four cities (Calgary, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Toronto) were selected for further examination. They were chosen for the following reasons:

- Calgary and Ottawa, because they had recently introduced new or revised prioritization criteria (evaluators hoped to learn what had led to the development of new or revised criteria and how the new criteria had addressed previous issues;

- Toronto, because it has approximately the same number of schools that AANDC oversees and might suggest best practices or lessons learned;

- Winnipeg, because the Province of Manitoba had been a focus of this evaluation; and

- Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario to complement the examination of the chosen cities.

Qualitative interviews were completed with individuals from the capital planning or facilities department in each location. A set interview guide was used for all interviews. Responses were coded and analyzed for common themes and findings.

Case Studies and Focus Groups

Eight case studies were conducted in four regions: Manawan and Natashquan in Quebec Region, Lac Seul and Wabaseemoong in Ontario Region, O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi and St. Theresa's Point in Manitoba Region, and Ahousaht and Nuxalk in British Columbia Region. Case studies included an examination of administrative documents and data, empirical on-site observations, and interviews with key respondents and focus groups.

The case studies provided qualitative and quantitative insights into whether the intended outcomes/ impacts of education facilities and other community infrastructure activities are occurring. These case studies also allowed for the identification of needs and best practices in order to determine where disparities exist in the quality of services being provided to First Nation communities across the country.

The following factors were considered in the identification of case study communities: regions with the highest number of capital assets, regional variations, community size, community remoteness, communities with recent and significant education facility investments (i.e., new schools), and communities that might suggest best practices or lessons learned. Evaluators also considered suggestions from regional offices and the Evaluation Working Group.

In the case studies, 80 community members were consulted either through interviews or focus groups. These included Chiefs and Council members, Education Directors, school principals and teachers, Band of Public Works/Community Infrastructure/Technical Services directors, Band managers and maintenance staff, and Chief Financial Officers/Chief Operating Officers, Band Economic Development Directors, and fire chiefs and firefighters, and Tribal Council members.

Case study research was led by Donna Cona Inc.

3.2 Evaluation Limitations

Limitations of the statistical analysis included an inability to disaggregate some data. For example, data could not be divided by the type of facilities because ACRS only distinguishes between the program's sub-activities. Thus, it was not possible to analyze data for individual facilities (i.e., roads, bridges, fire, offices, band offices), as these types of infrastructure were almost always coded as Other Community Infrastructure. Likewise, teacherages and school facilities all fell under Educational Facilities.

The statistical analysis was also limited by some irregularities in the database, such as typographical errors and missing information, which necessitated deletion of some entries. For example, the "Estimated Life Remaining" was reported to be "400 years" in one instance. In other instances, information was missing: the dates for 142 of the 20,168 facility inspections were missing, and thus, the entries had to be excluded from the analysis.

It was not possible to examine the data based on the program's different funding streams (major capital, minor capital, and O&M) due to limitations of the financial database.

Despite these limitations, the data provided a basic overview of the state of education facilities and other community infrastructure on-reserve.

4. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

Public infrastructure such as roads, schools, community buildings and communications systems must be adequately designed and maintained in order for communities to be safe, healthy and prosperous. Changing demographics, technological advances and modern work environments all necessitate the adaptation of public infrastructure to respond to evolving needs of citizens and their communities. Even assets that have been well-maintained are aging and need to be renovated and replaced.

In 2010, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities used results from a voluntary survey of 123 municipalities to report on the state of infrastructure in four categories: drinking-water systems, wastewater systems, waste-water and storm water networks, and municipal roads (2012, 1). The Federation of Canadian Municipalities estimated the national municipal infrastructure deficit for the 30 percent of infrastructure that is in the worst shape (30 percent) at $171.8 billion (Federation of Canadian Municipalities 2012, 3).

More recently, the Chief Executive Officer of the Assembly of First Nations testified before the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples regarding the infrastructure gap on-reserve. He used the Federation of Canadian Municipalities' estimates -- because there is no comprehensive tally of the infrastructure deficit for First Nations on-reserve -- stating that infrastructure on-reserve is experiencing a similar challenge to that of municipalities: assets are old and in need of repair and/or renovation, and changing demographics and technology contribute to the ever-widening infrastructure deficit (Senate 2014g).

4.1 There is a continued need for federal funding for First Nations infrastructure

In 2013, AANDC estimated the First Nations infrastructure deficit at approximately $8.2 billion, not including all school infrastructure, communications infrastructure, energy systems, roads or bridges (AANDC 2013d):

- $6 billion for housing;

- $1.2 billion for water/wastewater facilities;

- $878 million for school facilities; and

- $115 million for other infrastructure.

If unaddressed, the Department has estimated that the total infrastructure deficit in on-reserve First Nations communities will grow to $9.7 billion by 2018 (AANDC 2013d).

Although the challenges are also significant for many small and remote municipalities, there tend to be provincial and federal grants to finance their capital projects and own-source revenues such as taxes and user-fees to finance operations and maintenance. Conversely, the vast majority of First Nations rely heavily upon mostly on federal government investments alone (e.g., AANDC, Health Canada, and targeted federal funding such as the Building Canada Fund) for community infrastructure. Other source funding for First Nations communities infrastructure tends to be less robust and consistent (AANDC 2014d).

AANDC funds the majority of First Nations community infrastructure projects under the CFMP; however, CFMP funding is easily strained when the Department finds it must reallocate some of it towards statutory obligations, education, social programming and other federal priorities. Additional cost drivers for infrastructure include the two percent escalator cap (applied since 1997-98), population growth and inflation (AANDC 2013d). AANDC's recent evaluation of the First Nations Infrastructure Fund found that the First Nations Infrastructure Fund funded infrastructure projects on-reserve, which would otherwise often not receive CFMP funds – such as roads and bridges - due to the competing nature of more urgent priorities and the already strained CFMP budget (AANDC 2014d).Footnote 3

Site visits and key informant interviews suggest that the findings of evaluations conducted between 2010 and 2014 and those of the National Aboriginal Economic Development Board, continue to hold true in 2015: federal funding is crucial to the development and maintenance of major infrastructure on-reserve; and federal funding will remain crucial until all First Nations communities on-reserve are able to develop adequate, long-term and reliable own-source funding revenue streams (AANDC 2010, 13; the National Aboriginal Economic Development Board 2012; AANDC 2014d, 14-15, 34).

4.2 CFMP aligns with Government of Canada and AANDC priorities

Because infrastructure investment contributes to economic growth, job creation, and long-term prosperity, the Canadian government has made infrastructure development and improvement a national priority. "Annual federal support has increased from $571 million in 2003–04 to an estimated $5 billion in 2015-16" (Department of Finance 2015, 175). The federal government has made significant investments in infrastructure since 2006 through the Gas Tax Fund, the Building Canada Fund, and Economic Action Plan Stimulus funds.

The Gas Tax Fund was created to provide $5 billion over five years to Canadian municipalities, and in 2007, the Fund was extended and its annual budget increased to $2 billion. In 2011, legislation was passed to make this fund a permanent annual infrastructure investment. Between 2007 and 2013, the Gas Tax Fund provided $62.5 million in funding to First Nations through the First Nations Infrastructure Fund and $102 million for school infrastructure. As allocations for the Gas Tax Fund for First Nations are based on population on-reserve, this funding represents $139 million from 2014-2019 (Canada. Infrastructure Canada, 2014). Allocations for First Nations communities between 2019-2024 will be determined based on 2016 census data.

The Building Canada Fund was created in 2007 to provide $8.8 billion of infrastructure funding until 2014. In 2013, the Fund was renewed and will provide $155 million over 10 years for on-reserve infrastructure (Canada. Governor General, 2013).

In 2009, the Economic Action Plan Stimulus Fund was announced, promising an additional $7.5 billion in infrastructure funding, including $5.4 billion for provincial, territorial and municipal infrastructure, $1.7 billion for federal infrastructure, and $510 million for First Nations infrastructure.

| Budget Year | Funding | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Water | 82,500 | 82,500 | - | - | - | 165,000 |

| Housing | 75,000 | 75,000 | - | - | - | 150,000 | |

| Education Facilities | 95,000 | 105,000 | - | - | - | 200,000 | |

| 2010 | First Nations Water and Wastewater Action Plan |

- | 137,397 | 137,397 | - | - | 274,794 |

| 2011 | Fuel tanks | - | - | 10,000 | 12,000 | 13,000 | 35,000 |

| 2012 | First Nations Water and Wastewater Action Plan |

- | - | - | 137,397 | 137,397 | 274,794 |

| Education Facilities | - | - | - | 25,000 | 75,000 | 100,000 | |

| 2013 | Building Canada Fund | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 252,500 | 399,897 | 147,397 | 174,397 | 225,397 | 1,199,588 | |

These funds are in addition to Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program funding of approximately $7 billion over ten years for building, operations and maintenance of on-reserve infrastructure (Department of Finance 2013, 179).

Federal commitments toward investment in infrastructure have continued since 2010-11. In 2011-12, the Government committed to providing $175 million over three years toward school infrastructure improvement (Department of Finance 2012); and in 2014, the Government announced the establishment of a seven-year $500 million First Nations Education Infrastructure Fund for building and renovating First Nation schools, beginning in 2015-2016 (Department of Finance 2014). Budget 2014 also included funds to be directed toward other critical First Nations infrastructure needs, such as disaster mitigation, water and wastewater, and broadband connectivity (Assembly of First Nations 2014; Department of Finance 2014).

5. Evaluation Findings – Performance

Evaluators assessed CFMP performance by looking at spending, immediate outcomes, and intermediate outcomes against targets that the Department had set for itself.

As stated earlier in this report, both CFMP sub-programs had the same expected immediate outcomes:

- Infrastructure meets applicable standards and the needs of First Nation communities; and

- First Nation communities have capacity to maintain infrastructure.

The expected intermediate outcome for the Education Facilities sub-program was:

- First Nation communities have a base of education facilities that meets established standards.

The expected intermediate outcome for the Other Community Infrastructure sub-program was:

- First Nation communities have a base of safe community infrastructure (e.g., fire protection, electricity, safe roads and bridges, telecommunications) that meets established standards.

5.1 From 2009-10 to 2013-14, AANDC spent its budget of approximately $3.3 billion for Education Facilities, Other Community Infrastructure, and related operations and maintenance

Education Facilities

Between 2006 and 2014, the Government of Canada invested approximately $1.9 billion in school infrastructure, including new schools, major additions/renovations, other school projects, the operation and maintenance of existing assets and departmental operating costs. Of these investments, approximately $850 million was invested in 572 education facilities projects, including the construction of 41 new schools and 531 renovations, additions or other school projects.

With Canada's Economic Action Plan funds of $173.2 million, AANDC constructed nine new schools and made major renovations to three existing schools. (The remaining funding of $26.8 million was reallocated to water and wastewater Economic Action Plan projects).

Through the Building Canada Plan's Gas Tax Fund commitments of $102 million from 2009-10 to 2010-11, AANDC supported the construction of five new schools and two major renovations.

Economic Action Plan 2012 provided $175 million over three years for 11 new schools and two major renovations/additions, a proposal-based initiative for innovative and cost-shared school projects, and a project to examine the effectiveness of a public-private partnership to construct schools in four northern Manitoba communities.

Figure 1: Actual Spending for Educational Facilities, 2008-09 to 2012-13 and Planned Spending for Educational Facilities, 2013-14

Source: AANDC Integrated Financial System (2008-09 to 2012-13) and First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan (2013-14).

Text alternative for Figure 1

This stacked bar graph illustrates the amount of actual and planned funding for education facilities, from April 1st, 2008-09 to March 31st, 2013-14.

The X-axis shows the fiscal-year and Y-axis shows the funding received in millions of dollars.

2008-2009 shows funding of $107.90 million from A-Base (O&M); $92.07 million from A-Base (Capital); and $7.93 million from Budget 2006, for a total of $207.90 million.

2009-2010 shows funding of $108.86 million from A-Base (O&M); $62.05 million from A-Base (Capital); $24.51 from BCP/GTF; and $81.77 from CEAP, for a total of $277.19 million.

2010-2011 shows funding of $110.73 million from A-Base (O&M); $65.72 million from A-Base (Capital); $35.86 million from BCP/GTF; and $91.46 million from CEAP, for a total of $303.77 million.

2011-2012 shows funding of $114.67 million from A-Base (O&M); $55.03 million from A-Base (Capital); and $31.06 million from BCP/GTF, for a total of $201.30 million.

2012-2013 shows funding of $111.76 million from A-Base (O&M); $70.07 million from A-Base (Capital); $21.91 million from BCP/GTF; and $21.83 million from Budget 2012, for a total of $225.57 million.

2013-2014 shows funding of $107.18 million from A-Base (O&M); $67.70 million from A-Base (Capital); and $45.90 million from Budget 2012, for a total of $220.78 million.

A more detailed analysis of education facility spending between 2008-09 and 2012-13 shows more than 80 percent of capital expenditures were for new schools and/or major additions/ renovations in 44 First Nation communities. The average expenditure for a new school was $15.4 million (Figure 2).

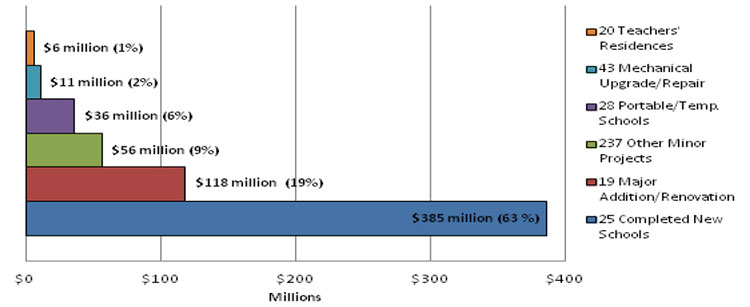

Figure 2: Education Facilities Capital Projects (2008-09 to 2012-13)

Source: AANDC Education Facilities Progress Report

Text alternative for Figure 2

This horizontal bar chart illustrates the 372 completed projects between April 1, 2008 and March 31, 2013, with a breakdown of $613 million by expenditure category. These categories are: Teachers Residences, Mechanical Upgrades and Repairs, Portable and Temporary Schools, Other Minor Projects, Major Additions and Renovations, and Completed New Schools.

The X-axis shows the expense in millions of dollars. The Y-axis shows the different project categories and the number of projects completed in each category.

The bar chart is sorted from top to bottom, beginning with the lowest expense at the top. This is detailed below:

- There are 20 new Teacher's Residences at an expense of $6 million, representing 1% of the total expenditure.

- There are 43 Mechanical Upgrade/Repair projects at an expense of $11 million, representing 2% of the total expenditure.

- There are 28 Portable/Temporary Schools at an expense of $36 million, representing 6% of the total expenditure.

- There are 237 other minor projects at an expense of $56 million, representing 9% of the total expenditure.

- There are 19 Major Additions/Renovations at an expense of $118 million, representing 19% of total expenditure.

- There are 25 Completed New Schools at an expense of $385 million, representing 63% of total expenditure.

Other Community Infrastructure

Evaluators found a breakdown of departmental spending by region for the Other Community Infrastructure sub-program (Figure 3), but with the exception of fire safety and connectivity, no breakdown of expenditures or project count by priority (fire safety, school safety, energy/electrical systems, connectivity). Evaluators were advised that systematic tracking of projects and spending by priority had been introduced two years ago, but the data had not yet been analyzed. Amounts marked as spending in the Northwest Territories and Yukon were applied toward projects in northern Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

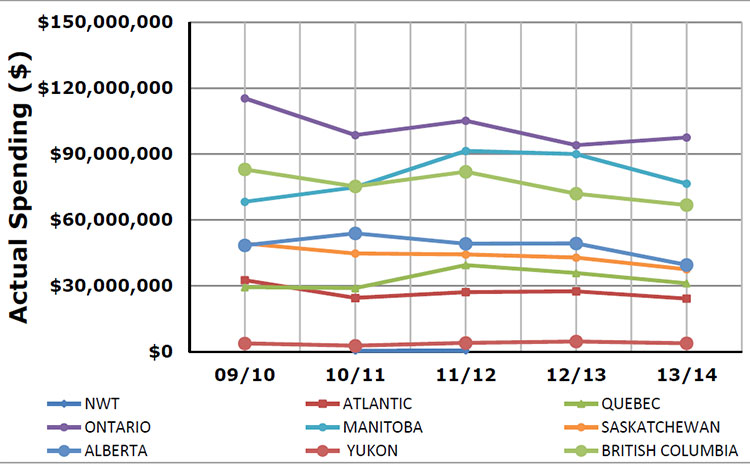

Figure 3: Spending for Other Community Infrastructure, 2009-10 to 2013-14

Text alternative for Figure 3

This figure shows a line graph indicating a breakdown of departmental spending by region for the Other Community Infrastructure sub-program. Actual spending is indicated along the vertical y axis for the years indicated on the horizontal x axis (2009-10 to 2013-14).

The graph illustrates that:

- Spending by the Yukon, represented at the bottom is almost nil and stays like that throughout the 5 year period.

- Spending by Quebec is at $30 million, increased in 2011-12 to about $45 million then dipped back to around $30 million.

- Spending by the Atlantic is around $30 million, decreasing in 2010-11 and staying almost the same through the years up to 2013-2014.

- Spending by both Saskatchewan and Alberta were the same in 2009-2010, around $50 million, but while Alberta's peaked in 2010-11 close to $60 million, at the same time Saskatchewan's dipped slightly below $50 million in 2013-14, both dipped to just below $50 million.

- Spending by Manitoba was around $70 million in 2009-2010, rose to about $80 million in 2010-2011 and $90 million in 2011-2013 then dipped back down to around $70 million.

- Spending by British Columbia was around $80 million in 2009-2010, dipped to around $75 million in 2010-2011, rose back to about $80 million 2011-12, dipped back down to around $75 million and further down to around $75 million in 2013-14.

- Spending by Ontario was around $191 million in 2009-2010, dipped to around $95 million in 2010-2011, rose back to about $110 million 2011-12, dipped back down to around $95 million in 2012-13 then rose slightly above $95 million in 2013-14.

- While NWT is featured in the legend, there is no spending associated with it.

Evaluators were not able to complete a breakdown of expenditures by category (Major Capital, Minor Capital, or Operations and Maintenance) due to data quality issues.

Connectivity was a priority because the Government considers it imperative that Canada's Aboriginal communities have access to reliable high-speed internet. Broadband infrastructure is seen as a critical tool for improving health and safety, increasing social well-being, and providing economic development and growth opportunities for Aboriginal communities. Access to the world-wide web can help Aboriginal learners reach their full academic potential and acquire the jobs and skills to compete in the labour market.

The Government's funding, therefore, has focused on ensuring that Aboriginal people are included in rural broadband infrastructure networks and obtaining broadband access comparable to access in non-Aboriginal rural communities. The Department has spent approximately $50 million since 2009-10 on connectivity projects, connecting 274 First Nations. In the process, a total of approximately $150 million was leveraged from other federal departments, provinces, and the private sector.

With respect to fire protection projects on-reserve, which are included in CFMP infrastructure investments, it was found that between 2009-10 and 2013-14, approximately $26 million per year was spent on First Nations fire protection projects (AANDC 2015a). Fire protection infrastructure projects include the planning, design, construction, operation, maintenance, repair, renovation and replacement of fire halls, fire trucks, and firefighting equipment (AANDC 2014e; AANDC 2015a).

5.2 Despite departmental processes to ensure effective construction and construction monitoring, there are still buildings being constructed in First Nation communities that do not meet applicable codes and standards

As a condition of funding, AANDC requires that First Nations adhere to federal and provincial statutes and regulations for the design, planning, construction, and maintenance, etc, of AANDC-funded capital assets (AANDC 2014e, §1,1). Qualified third parties hired by First Nations to provide these services are also expected to meet them. Contribution agreements provide lists of applicable statutes, codes and regulations and AANDC's regional offices have professional engineers and other staff to provide technical advice and assistance.

Upon project completion, First Nations are expected to provide properly authorized completion reports with project data necessary to update the Department's Integrated Capital Management System.

The Department also encourages First Nations to do post-project assessments of completed work to ensure compliance with health, safety and environmental codes and requirements, identify deficiencies, and confirm that they have received value for money.

The principles that guide this arms-length departmental management approach are:

- First Nations are responsible for capital projects and are accountable to their community members for the successful completion of capital projects;

- First Nations must provide properly authorized completion reports to the Department with enough project information and data to update ICMS; and

- First Nations' completion reports must include certification by a qualified professional that national and provincial codes and standards have been met.

Despite these requirements, several key informants and case study interviewees expressed concern that some First Nation infrastructure may not have been built to standard and codes. For example, staff at a school with a new addition said that improper materials had been used and some work was not finished. As a result, the pipes burst and the school flooded in the winter. Further, the school was built on shifting ground, resulting in foundation and window cracks. In another community, the wood foundation of a new teacherage (i.e., a house or accommodations provided for a teacher by a school) had visible structural weaknesses. In another community, strong winds were causing deterioration to the community centre roof; here, the key informant suggested that winds should have been taken into account in the design and construction of the centre, because strong winds are common to the area.

Similar concerns were found in testimony from First Nations communities and from organizations that work with First Nation communities, to the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. For example, one witness stated that having a progress-compliant reimbursement process rather than a code-compliant process meant that assets could be poorly-built, but still funded through CFMP (Senate 2014a).

5.3. Some First Nations are not adequately maintaining community infrastructure built with AANDC funding, which raises health and safety issues, increases insurance costs, and reduces buildings' lifespan

The importance of good building maintenance and building documentation is explained in a 2013 British Columbia Housing report (RDH Building Engineering Ltd. 2013). This information is useful background for the evaluation findings related to maintenance. It says maintenance and care are necessary if building assets are to achieve their expected lifespans. Maintaining building assets will result in lower longer-term costs, protection of property and asset value, minimized disruptions to residents, and lower risks for property owners. "For a building that has been well designed, constructed and maintained, the assets can be expected to last their full predicted service lives. Conditions deteriorate over time as a result of a variety of factors such as weather (sunlight, rain, wind, snow and ice) and wear and tear (daily use by occupants of the building). Without adequate maintenance, the building assets will deteriorate faster and their service lives may be diminished."

Over the course of a building's lifecycle, the document says maintenance, repair, renewal and operating costs will be almost three times the cost of design and construction. Maintenance, repair, renewal and operating costs fall into four categories:

- operating costs: the costs of running a building, e.g., electricity, gas and insurance;

- maintenance and repair costs: the costs of activities to keep assets in good working condition, e.g., cleaning of debris from roof drains, washing of windows and inspection of sealants and small repairs;

- renewal costs: the costs to replace or refurbish assets when they have reached the end of their service lives, e.g., replacement of the roof every 15-25 years; and

- adaptation costs: expenditures required to adapt the building to the evolving needs of the users and to address new requirements and standards that may be imposed by public orders, e.g., a retrofit of fire safety equipment.

It goes on to say that to facilitate maintenance, the owner(s) should be given a package of reference documents regarding new building assets whenever projects are completed. The package should include key documents generated during the design, construction and commissioning of a new building or building rehabilitation project, such as:

- drawings, (which may be required for periodic inspections, repairs and renewal activities) and specifications (which provide information related to materials and components);

- warrantee certificates, because they represent contracts that materials and/or workmanship will meet a certain level of performance over a specified period of time, to protect the owner against premature failure;

- safety and test certificates, because they demonstrate that necessary inspections and other maintenance work associated with certain assets has been completed, e.g., documentation related to equipment that must be tested periodically like elevators, roof anchors, fire suppression systems, boilers and back flow prevention valves;

- a list of all contractors, consultants and other parties involved in the construction or rehabilitation project, because they have first-hand knowledge about the building; and

- building owners and contractors should record maintenance work, as evidence of care and diligence, for example, for insurance companies, and to help identify performance trends of building assets. This log could include:

- an asset inventory: basic attributes of building assets like age, quality, manufacture and estimated useful life,

- an equipment and supplies inventory: equipment and supplies that are stored on the premises and are essential to an effective maintenance program,

- charts, labels and markers: equipment tags that indicate the inspection dates of such equipment as fire safety devices and back flow protection valves,

- maintenance guides, information bulletins, and other reference documents to assist owners with the maintenance and renewal of building assets, and

- maintenance service agreements: agreements with various parties for routine inspections, periodic maintenance, and eventual renewal services relating to the building assets.

It is not known the extent to which these documents are being provided to First Nations by their construction teams.

Maintenance Gaps

Lack of proper maintenance has a negative impact on the structural integrity of community infrastructure, which in turn can negatively affect the health and safety of First Nations peoples With respect to schools in particular, the condition of school infrastructure (design and maintenance) is believed to impact student well-being and academic performance.

At a recent hearing, the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples heard testimony that inadequate maintenance was a contributing factor to the premature deterioration of infrastructure on-reserve, which had direct effect upon the well-being of First Nations people; preventative maintenance was often not performed, which meant that buildings were deteriorating more quickly than they could be fixed (Senate 2014a).

This issue was reflected in some key informant and case study interviews and was witnessed by evaluators themselves in some of their case study visits.

Many key informants expressed concern about a lack of preventive maintenance for community infrastructure. They told evaluators that work tends to be initiated only when significant problems arise. Evidence of inadequate maintenance was also witnessed by evaluators in some of their visits to communities. Evaluators heard that maintenance work is sometimes left undone because of strained budgets or a lack of on-reserve staff with the skills to perform needed preventative maintenance and repairs. Some said construction/maintenance work by external contractors was not done to standard, even after deficiencies were pointed out.

Building integrity was also reportedly negatively affected due to over-crowding and over-use (e.g., a school with too many students and teachers for the space); fire prevention equipment that was not available or did not work; and, a lack of accessible/affordable hydro power. On this last point, one key informant said that the community' school lacked power an average of 10 days a year, which affected both student performance and the building's physical condition.

Vandalism was also identified as a very serious issue with impact for the structural integrity and safety of infrastructure on-reserve. Evaluators themselves saw evidence in site visits to several communities. Evaluators heard that poorly-maintained buildings and buildings not occupied full-time, e.g., band offices, community centres and fire halls, were especially vulnerable to damage through vandalism.

With respect to the impact of infrastructure on educational outcomes, a 2006 literature review undertaken by Australian State Government of Victoria found several international studies that identified school infrastructure as a contributing factor (along with other factors such as curriculum, teacher quality, and school management) to education outcomes and student/staff well-being, once socio-economic background had been excluded.

Aspects of school infrastructure were identified to be "the quality of the facilities, the overall design and the implications for time spent on teaching and learning" (Australia 2006, 3). The review cited several studies to support the impact of infrastructure on education outcomes such as a British study that had examined over 900 schools and found a "statistically significant correlation… between capital investment and student learning"(Australia 2006, 3). Specific factors that have been found to improve student performance include: air movement/ventilation, thermal comfort, lighting, natural daylight, and acoustics. For example, one study of over 2000 classrooms found that students in classrooms with more daylight performed significantly better than their colleagues who sat in classrooms with less natural daylight (Australia 2006, 3-4).

Fire Protection

AANDC does not collect fire loss data, but found reports that fire losses in First Nation communities (deaths, injuries, property destruction) far exceed those in off-reserve communities (Senate, 2014a). A 2007 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation report said that the per capita fire incidence rate in First Nation communities was 2.4 times the rate in the rest of Canada, the death rate was 10.4 times the rate in the rest of Canada, the fire injury rate was 2.5 times the rate in the rest of Canada, and the fire damage per unit rate was 2.1 times the rate in the rest of Canada (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2007, 3).

A more recent article from the Globe and Mail, "Enforce Building Code On-Reserves," stated that five percent of all fires in Manitoba are in First Nation communities and account for half of all Manitoba First Nation on-reserve fatalities (The Canadian Press 2014).

AANDC contributes approximately $26 million annually toward fire protection services for First Nations (including equipment and infrastructure) and requires every First Nation to have a community fire protection plan. It also provides $226,000 per year to the Aboriginal Firefighters' Association of Canada for fire prevention awareness activities (AANDC 2014e, §2.3 and §5; AANDC 2015a.).

Evaluators found evidence that many communities do not have fire protection plans and that fire equipment is not always adequately maintained.

In 2012, a CBC report on a Manitoba Fire Commissioner's Office and Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs joint analysis said that 93 percent of 61 Manitoba First Nations did not have a plan for fire protection in case of emergency, nearly a third did not have a fire truck, 39 percent did not have a fire hall, and only 15 percent had enough hose to fight a fire (Puxley 2014)

In 2011, reports of the tragic death of an infant in a Manitoba First Nation house fire stated that the community's fire truck was broken, the fire truck keys had been lost, and there were no fire hoses (Puxley 2014).

Evaluators also saw evidence of fire protection infrastructure weaknesses in the First Nation communities visited. In one community, the only building with fire safety equipment was the childcare building. Other buildings had no smoke alarms, fire extinguishers, or signs about what to do in case of fire. In another community, the school fire alarm had been broken for more than a year and there was no sprinkler system, so the community was relying on volunteer school foot patrols when students were in the building.

Insurance

Another witness from the same company said a lack of building codes, fire codes and formal inspections in First Nation communities affect the willingness of insurance companies' willingness to insure such structures and their contents. Community insurance rates are also affected by an absence of legislation to support code compliance for on-reserve construction and the lack of a national building code for First Nation reserves.

The Standing Committee was told that there is an annual Fire Underwriter Survey of all aspects of all municipalities' fire services, including First Nations. Each community's Fire Services is given a 1 to 10 rating, which is taken into account by insurance companies when they set their rates (Senate 2015). This, too, was cited as a reason for higher insurance rates.

5.4 The Department was not able to meet its performance targets for either sub-program

In its 2013-14, Departmental Performance Report, AANDC reported on its performance against performance indicators of the Education Facilities and Other Community Infrastructure sub-programs.

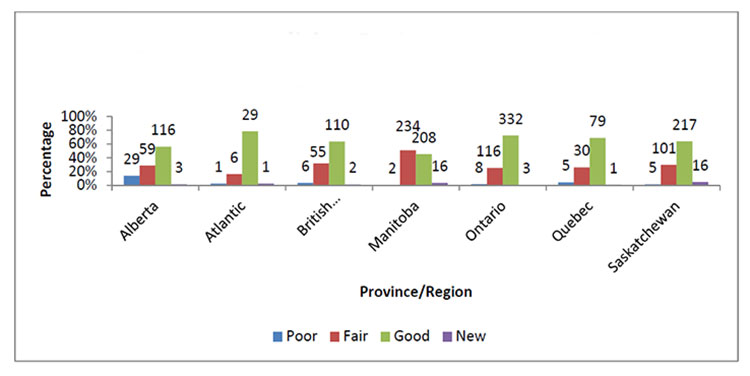

For the Education Facilities sub-program, the expected outcome was: First Nations communities have a base of education facilities that meet established standards. The performance indicator was the percentage of First Nations schools with a condition rating greater than fair, based on Asset Condition Reporting System records of physical/structural condition. The target for March 31, 2014 was 70 percent.

The Departmental Performance Report said that 63 percent of education facilities met established standards as of March 2014, i.e., performance fell short by seven percent. More recent data made available to evaluators suggests the percentage was still 63 percent in April 2015.