Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Quebec and Prince Edward Island for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program

Final Report

Date : November 2013

Project Number: 1570-7/12034

PDF Version (372 KB, 64 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings – Design and Delivery

- 5. What are the key factors that have facilitated or hindered the achievement of results?

- 6. Evaluation Findings – Performance (Effectiveness/success)

- 7. Evaluation Findings – Other results

- 8. Evaluation Findings - Efficiency and Economy

- 9. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Annex A – Bibliography

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| EPFA |

Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| FNCFS |

First Nations Child and Family Services |

| PRIDE |

Prevention, Respect, Intervention, Development and Education |

Executive Summary

This Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Quebec and Prince Edward Island is part of a multi-year Strategic Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach (EPFA) for the First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) Program, which began with an implementation evaluation in Alberta in 2009-10. The purpose of the strategic evaluation is to look at jurisdictions individually two-three years after the approach has been implemented to address issues of relevance, and to the extent possible, performance, efficiency and effectiveness. In 2010-11, a Mid-Term National Review was undertaken to consider the overall relevance of the EPFA, promising practices in prevention programming, as well as to provide some insight on discussions to establish tripartite frameworks to date. An implementation evaluation was completed for Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia in 2012-13. Following this current evaluation, an Implementation Evaluation is scheduled for Manitoba in 2013-14.

The FNCFS Program funds FNCFS agencies to provide culturally appropriate child and family services in their communities, in a manner reasonably comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar circumstances and geographic location within Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) program authorities. FNCFS agencies receive their mandate and authorities from provincial/territorial governments and function in accordance with provincial and family services legislation.

Starting in 2007, AANDC began reforming the FNCFS Program from a protection to a prevention focused approach on a jurisdiction by jurisdiction basis, beginning in Alberta.Footnote 1 Prevention services may include, but are not limited to, respite care, after-school programs, parent/teen counselling, mediation, in-home supports, mentoring and family education. AANDC, provincial and First Nations representatives must enter into a Tripartite Accountability Framework in order to move to an enhanced prevention model. The framework can vary from region to region but costing models developed at tripartite tables are based on reasonably comparable funding amounts provided to agencies by provincial governments in communities in similar geographic areas and circumstances.

In August 2009, Quebec First Nations and Prince Edward Island First Nations entered into partnerships with AANDC and their respective provincial governments to implement an Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach to deliver child and family services. As part of the EPFA, First Nations Child and Family Services agencies in Quebec received $59.8 million over five years in new funding, and the agency in Prince Edward Island received $1.7 million in new funding over five years.

In Quebec, 15 Aboriginal FNCFS agencies funded by AANDC serve 19 First Nations communities, and three youth centres run by the province serve the remaining eight communities.

There are two First Nations in Prince Edward Island and they are served by the Mi’kmaq Confederacy’s of Prince Edward IslandFootnote 2, which provides culturally appropriate family and community services to Aboriginal families through the Mi’kmaq Family PRIDE (Prevention, Respect, Intervention, Development and Education) Program. Funded by AANDC, the program provides prevention services and supports the protection of children in both First Nations in Prince Edward Island.

Methodology

The evaluation supports the following key findings regarding relevance, design and delivery, performance/effectiveness and efficiency/economy based on the analysis and triangulation of five lines of evidence: document review; literature review; 32 key informant interviews; a survey; and three case studies.

Key Findings: Relevance

A prevention focused approach is needed in light of the fact that First Nation children are over represented in the child welfare system, and further, protection alone cannot resolve all the pressing social issues in First Nations communities across Quebec and Prince Edward Island, where risk factors (e.g. poverty; substandard and overcrowded housing; mental health problems and addictions; historical traumas) are prevalent. The evaluation notes that by itself, the EPFA has neither the authority nor the capacity to address all these issues directly. The EPFA is an integral component of a broader continuum of program and services required to address these challenges. As such, the EPFA continues to be needed and relevant.

There is strong alignment between the EPFA objectives and commitments made by the Government of Canada (e.g., past budgets, speeches, Cabinet directives, etc.). Budgets 2006 and 2010 and the 2011 Speech from the Throne confirm that the EPFA’s objectives remain a key priority for the federal government. Departmental support for FNCFS EPFA as a priority is also evidenced by the financial support devoted to the FNCFS. Funding is provided for the delivery of protection and prevention services to support this commitment and, in compliance with this priority, AANDC, since 1998, has steadily increased funding to the provinces, Yukon and to more than 100 FNCFS agencies who are responsible, under provincial or territorial law, for the delivery of child and family services within their jurisdiction. So far, AANDC funding to these service providers has more than doubled over the 14 years, from $238 million in 1998-1999 to approximately $618 million in 2011-2012.

As provinces and territories have jurisdiction over child welfare both on and off reserve, AANDC operates the FNCFS EPFA with the objective of funding the provision of child welfare services that are culturally appropriate, that comply with provincial legislation and standards, and that are reasonably comparable with services provided off reserves in similar circumstances. The EPFA is perceived by key informants as consistent with the roles and responsibilities of the Government of Canada with respect to promoting and maintaining the welfare of the Aboriginal population.

Key Findings: Design and Delivery

All of the agencies in Quebec and Prince Edward Island recognize the crucial role prevention plays in reducing risks that contribute to social problems. The evaluation determined that the majority of agencies are progressing towards the effective implementation of the EPFA. The design and implementation of an effective prevention approach depends on several factors, such as availability of qualified and experienced local staff, office space, lodging for workers in geographically isolated communities, extensive use of partnerships with other service delivery agents, proximity to an urban centre, and support and leadership from the Band Council.

Key Findings: Performance/Effectiveness

Community members are generally aware of the prevention activities that are available to them and the majority of communities reported a high participation rate in prevention programming by children. However, the case studies and interviews found that there were concerns that the participation of parents could be improved. With respect to having access to culturally relevant services, all lines of evidence demonstrate that the agencies in both Quebec and Prince Edward Island have implemented prevention activities that were respectful of the community’s culture. Overall, in communities where the approach is being successfully implemented, the first signs of transformation among parents and children are beginning to appear; parents are becoming increasingly responsible and children are gaining more confidence.

Although it is too early to draw conclusions about the reduction of the number of children in care, the implementation of the EPFA is showing some early successes. In Gesgapegiag, there was a reduction in the number of children placed in foster homes from twelve in 2010 to four in 2012 (67 percent decrease). In Mashteuiatsh First Nation, there was a reduction in the number of children placed in foster homes from 63 in 2008 to 43 in 2012 (32 percent decrease). In Prince Edward Island, there were two First Nation children in the care of the province. One child will age out in July 2013 and the other in two years. Further, since PRIDE has been in place no child on reserve has become a permanent ward of the province. Sixteen children were supported by PRIDE who may have otherwise gone into care. PRIDE has been working to identify the least intrusive supports within the community such as Aboriginal kinship homes.

Key Findings: Efficiency / Economy

The majority of agencies in Quebec, and the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island are implementing the EPFA in a cost effective manner. One of the key factors that has contributed to cost-effective implementation has been the extensive use of partnering with other service delivery agents. These collaborations help to provide a continuum of services and lower costs because each partner contributes its own expertise and resources. In cases where First Nation personnel do not have a full-spectrum of skills, partnerships enable the agency to obtain support from other qualified professionals.

Lastly, according to the literature, prevention programs that increase the well-being of children and families can reduce both the short-term and long-term cost of providing child welfare services.

Based on these findings, it is recommended that:

- Headquarters ensure that the expected outcomes and performance measures for the EPFA are clearly distinguished and articulated in the Social Development Performance Measurement Strategy.

- Regional staff and Headquarters improve the monitoring and reporting of the EPFA by:

- providing guidance and monitoring of the agencies’ implementation of a results-based management approach that integrates planning, resources, activities and performance measurements to improve decision making, transparency, and accountability; and

- ensuring that prevention activities are reported based on the expected outcomes for the EPFA, and that expenditures on prevention activities are tracked and reported.

- Headquarters assess the costing models on a regular basis and revise as appropriate to ensure that they are not outdated.

- Facilitate the creation of a mentoring network among the FNCFS agencies in order to increase their capacity by providing opportunities for sharing experiences and practical knowledge.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Quebec and Prince Edward Island for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program

Project #: 1570-7/12034

The First Nations Child and Family Services program agrees with the recommendations produced in this Strategic Evaluation, and would like to provide some context to clarify the degree to which AANDC will be able to implement some of these. This is especially important with respect to Recommendations 2(a), 3 and 4. Recommendation 2(a) is "Providing guidance and monitoring of the agencies' implementation of a results-based management approach that integrates planning, resources, activities and performance measurements to improve decision-making, transparency, and, accountability". AANDC's role for FNCFS is that of a funder for provincially-delegated agencies. AANDC is limited in how much it can "provide guidance and monitoring of agencies" especially at the detailed level of the agencies' implementation of their results-based management approach. This is primarily a provincial role as provinces are responsible for ensuring agencies are delivering services in accordance with provincial legislation, standards, directives, policies and practices. Recommendation 3 outlines the need for. "Headquarters to assess the costing models on a regular basis and revise as appropriate to ensure that they are not outdated." AANDC can review costing models under EPFA, however, any changes to costing models that result in increased funding will create cost pressures on the program that may not be able to be addressed without seeking external funding sources (reallocations within AANDC or new funding). Recommendation 4 is to "Facilitate the creation of a mentoring network among the FNCFS agencies in order to increase their capacity by providing opportunities for sharing experiences and practical knowledge." The pace to which we can respond to these recommendations will depend on available resources.

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Headquarters ensure that the expected outcomes and performance measures for the EPFA are clearly distinguished and articulated in the Social Development Performance Measurement Strategy. | 1a. Headquarters will develop an annex to the AANDC Social Development Performance Measurement Strategy at the sub-program level (2.2.4) for Child and Family Services. This annex will clearly articulate details, expectations, expected results and indicators associated with the sub-program's activities, including the EPFA. 1b. Headquarters will return to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in April 2014 to seek approval for the sub-program Performance Measurement Strategy Annex (to be appended to an amended version of the program's Performance Measurement Strategy) and to table its annual update on the Social Development Performance Measurement Strategy. |

Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: Winter 2013 |

| Completion: April 2014 |

|||

2. Regional staff and Headquarters improve the monitoring and reporting of the EPFA by:

|

|

Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: Fall 2013 |

| Completion: Fall 2014 |

|||

| 3. Headquarters assess the costing models on a regular basis and revise as appropriate to ensure that they are not outdated. | AANDC will participate in tripartite meetings with provinces and agencies on EPFA implementation, which will include reviewing the costing associated with EPFA. AANDC Headquarters will also continue to liaise with Regions through monthly conference calls and regular meetings to review financial pressures that may arise during EPFA implementation. These meetings and discussions will allow Headquarters to determine whether pressures can be addressed and forecast future costing, while also allowing Headquarters and regions to develop possible mitigation strategies for arising issues. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: Fall 2013 |

| Completion: Ongoing |

|||

| 4. Facilitate the creation of a mentoring network among the FNCFS agencies in order to increase their capacity by providing opportunities for sharing experiences and practical knowledge. | AANDC will continue to provide funding for regional tripartite table meetings. AANDC will encourage partners to make use of regional tripartite meetings to encourage networking and sharing experiences and practical knowledge amongst agency representatives. AANDC will also promote other existing networks such as social media that maybe used for this purpose. Use of resources will focus on building agency networks in the regions necessary to positively impact the health and well-being of the child, youth and guardian population, aligned with their respective priorities as identified in their business plans. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: Fall 2013 |

| Completion: Fall 2014 |

|||

|

Table 3 Source: Statistics Canada, 2011 NHS,AANDC Special Tabulations. |

|||

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed by:

Françoise Ducros

Assistant Deputy Minister, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Quebec and Prince Edward Island for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Quebec and Prince Edward Island is part of a multi-year Strategic Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach (EPFA) for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program, which began with an implementation evaluation in Alberta in 2009-10. The purpose of the strategic evaluation is to look at jurisdictions individually two-three years after the approach has been implemented to address issues of relevance, and to the extent possible, performance, efficiency and effectiveness. In 2010-11, a Mid-Term National Review was undertaken to consider the overall relevance of the EPFA, promising practices in prevention programming, as well as to provide some insight on discussions to establish tripartite frameworks to date. An Implementation Evaluation was completed in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia in 2012-13. Following this current evaluation, an Implementation Evaluation is scheduled for Manitoba in 2013-14. Further evaluative work will be considered as agreements are reached in remaining jurisdictions.

The report is divided into five parts as follows:

- program description;

- methodology;

- findings;

- unplanned results; and

- conclusion and recommendations.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

The First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) Program funds FNCFS agencies to provide culturally appropriate child and family services on reserve in a manner reasonably comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar circumstances within program authorities. To this end, the program funds and promotes the development and expansion of child and family services agencies designed, managed and controlled by First Nations. Since child and family services is an area of provincial jurisdiction, these First Nation agencies receive their mandate and authorities from provincial governments and function in accordance with existing provincial child and family services legislation.

Government funding for child welfare is complex, and involves both bilateral and trilateral agreements between Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), the 105 First Nations Child and Family Services agencies funded by AANDC, the 10 provinces and Yukon Territory. In areas where First Nations Child and Family Services agencies do not exist, AANDC funds services provided to First NationFootnote 3 children and families on reserve by provincial or territorial organizations or departments.

In 2007, the FNCFS Program began its reform to the EPFA from the previous funding model for all jurisdictions except Ontario and AlbertaFootnote 4 known as Directive 20-1. Directive 20-1 has been in place since April 1, 1991. It places increased emphasis on early intervention and family supports and funds according to a formula for operations (including limited prevention services) and reimburses for eligible maintenance expenditures, based on actual costs.

The EPFA reorganized the FNCFS Program's funding structure to include three targeted streams of investment – maintenance, operations, and prevention/least disruptive measures – that are eligible for use for Child and Family Service activities, though FNCFS agencies have the ability to move money between the three streams to better meet their needs.

The EPFA represents a refocusing of FNCFS funding towards a more prevention-based approach. Prevention services may include, but are not restricted to, respite care, after-school programs, parent/teen counselling, mediation, in-home supports, mentoring, and family education. Prevention services may also assist in the earlier and safe return of a child to their family. The rationale for this shift is that the implementation of prevention services in the early stages of a child's life often mitigates the need to bring children into care, and thereby supports keeping First Nation families together. This is consistent with provinces that have largely refocused their own Child and Family Service services/system from protection to prevention services.

The EPFA supports:

- Families getting the support and services they need before they reach a crisis;

- Community-based services and the child and family system working together so families receive more appropriate services in a timely manner;

- First Nations children in care benefitting from permanent homes (placements) sooner by, for example, involving families in planning alternative care options;

- Services and supports co-ordinated in the way that best helps the family; and

- Coordination of services – funding for staff/purchase services.

To date, six jurisdictions covering approximately 68 percent of all First Nation children ordinarily living on reserve are currently under the EPFA modelFootnote 5 and work is underway to move the remaining jurisdictionsFootnote 6 to the EPFA as soon as possible.

AANDC's FNCFS programming is funded through the following authority: Payments to support Indians, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in social development (support culturally appropriate prevention and protection services for Indian children and families resident on reserve), and is derived from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-6, s.4 and subsequent policy proposals.Footnote 7 Under AANDC's Program Alignment Architecture, the program falls under the Strategic Outcome ‘The People,' which aims to promote "Individual and family well-being for First Nations and Inuit."

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

AANDC funds a suite of social programming, including the First Nations Child and Family Services Program, the Family Violence Prevention Program, the Income Assistance Program, the National Child Benefit Reinvestment Program and the Assisted Living Program. The overall objective of AANDC's social programs is to "provide funding to First Nations administrators to provide on-reserve residents with individual and family supports and services that have been developed and implemented in collaboration with partners in order to contribute to:

- fostering greater self-sufficiency for First Nation individuals and communities;

- improving the quality of life on reserve;

- creating a community environment where incidences of family violence and child abuse are reduced or eliminated; and

- supporting greater participation in the labour market and fully sharing in Canada's economic opportunities."Footnote 8

More specifically, the objective of the FNCFS Program is to ensure the safety and well-being of First Nations children and their families on reserve by supporting culturally appropriate prevention and protection services, in accordance with the legislation and standards of the province or territory of residence. In addition, the incremental investments of the EPFA are expected to help agencies to stay aligned with emerging provincial practices focused on early intervention services.

According to the original program documentation, the immediate outcome expected from EPFA investments was increased access to services that protect children and families at risk at a standard reasonably comparable to non-First Nations communities in similar circumstances. Social workers are expected to be able to strengthen partnerships through horizontal integration with other community services/organizations for better case management (i.e. through case conferencing) to improve service delivery and provide integrated responses to meet the real needs of First Nation children and families. Capacity development support would be provided to smaller agencies that may lack the economies of scale to deliver the full continuum of services.

At the time of data collection for this evaluation, the performance measurement strategy was being revised to improve performance reporting. Currently, the outcomes for the FNCFS Program are captured in the Evergreen Performance Measurement Strategy for Social Development Programs. This Performance Measurement Strategy is meant to reflect the higher level outcomes expected for the current suite of five social development programs funded by AANDC and delivered to First Nation communities. It sets out AANDC's accountability with respect to measuring, managing and reporting on the expected results for the five programs. There are no specific outcomes that apply solely to the FNCFS EPFA, but rather three broader outcomes that apply to the FNCFS Program as well as other applicable AANDC social programs.

The relevant immediate outcome for the FNCFS Program is that "men, women and children in need or at-risk have access and use prevention and protection supports and services." This outcome is attributable to both the Family Violence Prevention Program as well as the FNCFS Program and is described as follows: "Prevention and protection supports and services will be made available to men, women and children on reserve and these supports and services are expected to address a variety of situations. The focus on providing prevention supports and services to those at-risk is in line with the approach taken by most provinces when addressing children at risk and family violence. Prevention supports and services include, for example, respite care, counselling, in-home supports and family education. Protection supports and services include, for example, shelters for women and families, and foster care, institutional care and group home services for children."

Key indicators for this outcome include: percentage of First Nations men, women and children in need or at-risk, ordinarily resident on reserve, that are using prevention and protection supports and services and rates of ethno-cultural placement matching. The first indicator is meant to determine the extent to which prevention and protection supports and services either on or off reserve, or on another reserve, are available to First Nations ordinarily resident on reserve, and the latter adopts the National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator MatrixFootnote 9, which states: "Given that placement matching for AboriginalFootnote 10 children is legislated in most jurisdictions, the priority National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix measure tracks the proportion of placed Aboriginal children in homes with at least one of the caregivers is Aboriginal."Footnote 11

Intermediate outcomes according to original program documentation were expected to include a more secure family environment, reduced need for the removal of children from parental homes, reduced incidents of abuse, and overall improvement in child well-being. To measure attainment of this goal, more quantifiable outcome data was to be gathered. At the planning phase of this approach, AANDC committed to partner with provinces and First Nations to ensure that First Nations' indicators can be extracted directly from the provincial database.

In the current performance measurement strategy, this intermediate outcome translates to "Men, women and children are safe." This outcome applies to the FNCFS Program and the Family Violence Prevention Program, and is described as follows: "With access to prevention-focused supports and services that are designed, for example, to enable children to remain safely in the family home, to prevent the kinds of situations that give rise to family violence or to prevent elderly people from having to leave their homes, better outcomes are expected for those affected. Providing supports that enable children to stay in the family home safely is expected to result in children that are not only safe but also benefit from a more stable environment. It is also expected that the prevention projects undertaken by First Nation service providers (e.g. training, awareness and conferences) will increase the capacity of First Nation to meet the various needs of their communities and avoid escalation of situations to the point where people need to access protection services. Early intervention or enhanced prevention approaches, as contemplated by prevention services, are expected to reduce the number of families and individuals who reach a crisis state in their personal or family situations. If the issues leading to situations of family violence can be addressed early, such crises may be avoided entirely. Such services are also critical in addressing the issues that led to the crisis in the first place in order to avoid recurring incidents.

Having access to protection supports and services for men, women and children on reserve, such as a shelter, does ensure the immediate safety of those who must leave a violent domestic situation. In addition, having access to various options for a child that must leave the family home (e.g. out of home placements, kinship care) also provides immediate safety as the child is removed from an unsafe situation. The availability of shelters or similar safe locations for men, women and children that provide a haven to escape violent situations or unsafe environments is expected to result in men, women and children that are safer. Once safety is no longer a concern, men and women, for example, are able to step away from their chaotic environment and make choices for themselves through the community prevention programs and services available, thus, creating a more stable environment for themselves and their families."

At the time of this evaluation, performance measures for this outcome included mortality rates, injury rates and recidivism rates. The mortality rates indicator was reflective of the National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix indicator "percentage of children who die while in the care of child welfare services," and is meant to assess the overall conditions of safety. The purpose of measuring injury rates was to assess overall safety in the communities and was reflective of the National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix indicator "serious injury and death." Finally, recidivism rates were expected to reflect the long-term effectiveness of services, and are also reflective of National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix. In the current performance measurement strategy, these indicators have been replaced with a performance indicator on ‘recurrence rates'. This indicator speaks to the long-term effectiveness of services as well as safe environment by measuring the percentage of clients who received prevention and/or protection services and did not require protective services within 12 months of file closure. This indicator applies to all clients, however, for children in care, the National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix indicator states "recurrence is the proportion of children who are investigated as a result of a new allegation of abuse or neglect within one year following closure of their child welfare file".

The expected ultimate outcome for the FNCFS Program is to have a more secure and stable family environment for First Nation children ordinarily resident on reserve. This outcome applies to all five of the social programs and is described as follows: "The social supports and services delivered are targeted at at-risk individuals and families that often face multiple barriers and challenges. Addressing the basic and special needs of individuals, ensuring a level of safety for those at risk, and providing supports to enable men and women to get into the paid work force is expected to result in men, women and children who are then in the position to address any additional needs they may have and to take advantage of other opportunities provided by their First Nations communities. When basic needs have been addressed, individuals are able to take the steps necessary to address their other needs, whether through participating in the paid or volunteer workforce or through accessing other programs to address related needs such as housing, education or health."

There are two performance indicators for this outcome that are applicable to the FNCFS programs. The first is: ‘rates of permanency status achieved (Child Specific)'. This is a National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix indicator and measures the cumulative days in care until a child is reunified, permanently placed with kin, adopted, emancipated, or placed in a permanent foster home. Permanency status is tracked forward from a child's initial placement for up to 36 months, at which point permanence is not considered to have been achieved. Lasting reunification with family is the primary goal for most children placed in out-of-home care, and a majority of children will return home within less than a year of their initial placement. However, for some children reunification is not possible and stable alternatives such as permanent foster care, kinship care, and adoption must be pursued.

The second indictor is: "percentage of communities using innovative community-driven approaches to program delivery". This indicator measures the contribution of social programming to First Nation communities that are then able to make it possible for First Nation men, women and children to be offered different approaches to being involved within social development within their communities to improve their social well-being. It assesses whether or not alternative approaches to governance or other models improve the health and social outcomes of First Nation men, women and children.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

AANDC Headquarters establishes on a national basis the program guidelines, the terms and conditions that must be included in each funding arrangement, as well as the policy related to monitoring and compliance activities. The specific role of Headquarters is to:

- Provide, through the regions, funding for recipients to provide services to children and families as authorized by the approved policy and program authorities;

- Lead in the development of FNCFS policy;

- Consider proposals for change coming from regional representatives and First Nations practitioners;

- Provide oversight on program issues related to the FNCFS policy as well as to assist regions and First Nations in finding solutions to problems arising in the regions;

- Provide leadership in collecting data and ensuring that reporting takes place in a timely manner;

- Interpret FNCFS policy and assist regions in providing policy clarification to recipients, provinces and territories; and

- Provide amendments to the National Program Manual as required and to ensure that program policy documentation is consistent with approved policy and program authorities.

With the support of regional staff, the Regional Director General in each region is responsible for implementing and administering the social development programs in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the National Program Manual. This includes, for example:

- assessing the eligibility of recipient applications and eligibility of expenditures;

- entering into financial arrangements with approved recipients in accordance with the transfer payment Terms and Conditions; and

- monitoring, collecting and assessing both the financial and program performance results of individual recipients, and taking appropriate remedial action.

FNCFS falls within provincial/territorial jurisdiction. It is the role of the province or territory to:

- Mandate recipients in accordance with provincial or territorial legislation and standards;

- Regulate recipients in their activities as they relate to the legislation and standards;

- Provide ongoing oversight to recipients and to take action if the requirements are not being met;

- Participate in tripartite activities such as negotiations, dispute resolution and consultations as well as regional tables;

- Apply the legislation and standards for all child and family services equally to all residents of the province or territory on and off reserve;

- Provide information on outcome data to the federal government; and

- Adhere to other roles and responsibilities as determined through agreements, such as the Tripartite Accountability Framework.

FNCFS agencies are responsible for delivering the FNCFS Program in accordance with provincial legislation and standards while adhering to the terms and conditions of their funding agreement. FNCFS service providers include, but are not limited to, First Nations (as represented by chiefs and councils); and their organizations such as tribal councils or agencies (such as Child and Family Service agencies in various communities).

Eligible recipients for FNCFS funding are:

- Councils of Indian Bands recognized by the Minister of AANDC;

- Tribal councils;

- FNCFS agencies or societies duly mandated by the relevant province/territory;

- Provincial/territorial government;

- Other mandated Child and Family Service providers, including provincially mandated agencies/societies; and

- First Nations and First Nations organizations who apply to deliver capacity-building activities, including the development of newly-mandated FNCFS programs.

Beneficiaries of the FNCFS Program include at-risk First Nations children and their families on reserve that require access to prevention/least disruptive measures services and/or child protection services, including child placement out of the parental home.

1.2.4 The EPFA in QuebecFootnote 12

In Quebec, 15 FNCFS agencies funded by AANDC serve 19 First Nations communities, and three youth centres run by the province serve the remaining eight communities. Based on the level of community responsibility for services, various types of agreements are concluded between AANDC, the band councils (agencies) and/or the youth centres to determine the roles and responsibilities of each party. These agreements also specify the level of delegation in on-reserve application of the provincial Youth Protection Act. Delegation is a prerequisite for AANDC service funding.

The Province of Quebec has been providing prevention services for over 25 years to the Quebec population. In October 2006, First Nations, the Government of Quebec and the federal government signed a tripartite agreement creating first-line intervention pilot projects over a three-year period in order to reduce the caseload and child placement in several communities in Quebec.

On June 16, 2007, a policy monitoring meeting approved prevention services within the FNCFS Program for the Quebec communities as a whole. At that time, Quebec had already been implementing some prevention measures. For example, the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec's Plan stratégique 2005–2010 noted the application of prevention services delivered to at risk youth and their families. The preferred approach involves continuous early intervention, within the community if possible, to prevent the worsening or recurrence of social adaptation problems experienced by youth and their families.

During this same period, Law 125, An Act to amend the Youth Protection Act and other legislative provisions came into effect on July 9, 2007. The Law encourages keeping children with their families or returning them to their families as early as possible. It also establishes specific time limits for foster care placements depending on child's age and the concept of continuity of care, stable relationships and stable living conditions corresponding to the child's needs and age on a permanent basis. In addition, it stipulates that parental involvement must always be favoured and that parents are entitled to health and social services.

In 2009, Quebec First Nations entered into a Tripartite Framework Agreement with AANDC and the provincial government to implement an Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach to deliver child and family services. As part of the EPFA, First Nations Child and Family Services agencies in Quebec received approximately $59.8 million over five years in new funding, in addition to existing Child and Family Services Program funding.

The Quebec EPFA Design

To implement the EPFA, the tripartite committee partners, namely the First Nations of Québec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission, AANDC – Quebec Regional Office and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux through the Partnership Framework for the EPFA, established the parameters for an enhancement initiative to create quality, community-based, integrated, culturally appropriate First Line Prevention Services for the benefit of First Nations children, families and communities. The Partnership Framework affirms that First Nations communities must take the lead in developing and implementing these services.

Through the Partnership Framework under the EPFA each First Nation was expected to design its own prevention model taking into account their specific social conditions, capacity, and authority using a community-based social development approach focusing on:

- Life promotion;

- The healthy development of the children and families; and

- The fight against poverty and social exclusion.

As well, where all of the children and their families have access to quality services that:

- Are controlled by the community;

- Are culturally appropriate;

- Promote the use of their language; and

- Allow all children and their families and communities as a whole to achieve their full potential, since they are the ones who will create a better future for everyone.

Some of the specific objectives promoted within the Partnership Framework for the FNCFS's First-Line Services are:

- Prevent and reduce the rate of reported cases and the number of cases in which the authorities take over responsibility for the child;

- Prevent and reduce the number and length of placements outside the family and community of origin;

- Promote and reinforce early intervention with children and parents before the family situation can worsen;

- Act on the main risk and protection factors; and

- Develop individuals' and communities' strengths and skills.

In line with most other FNCFS operative mandates across the country, the Quebec First-Line EPFA program operates within the provincial mandate of offering youth protection services to First Nations communities. The Quebec Government's mandate for youth protection falls under the "Youth" (Child) Protection Act, last updated June 1, 2013, which offers services regarding protection exclusively, and not for prevention. Within Quebec, prevention services are delivered exclusively under the authority of the Quebec Health and Social Services Act and the Quebec Government through the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux and provincial networks have been supporting the development and implementation of First Line services through the Partnership Framework to prevent abuse and neglect.

1.2.5 The EPFA in Prince Edward Island

There are two First Nations in Prince Edward Island: Lennox Island and Abegweit. Although Prince Edward Island does not have a delegated First Nations child and family service agency, these two communities have formed the Mi'kmaq Confederacy's of Prince Edward Island. The Mi'kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island is a Tribal Council organization established in 2002 to represent the common interest of the Abegweit and Lennox Island First Nations. The Mi'kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island provides a range of services, including the Mi'kmaq Family Prevention, Respect, Intervention, Development and Education Program (PRIDE). Funded by AANDC, the PRIDE program provides culturally appropriate family and community services to both First Nations in Prince Edward Island.

In line with most other FNCFS operative mandates across the country, the Mi'kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island PRIDE program operates within the provincial mandate of addressing the needs of First Nations communities. The Prince Edward Island Government's mandate for child protection and prevention services falls under the order of their Child Protection Act of May 2003, (originally implemented in 2003 and amended in 2010), which offers services regarding protection, but not for prevention. Nonetheless, it provides guidance on the shared responsibility of individuals within families, the community, and the province, to act to prevent abuse and neglect.

The Province of Prince Edward Island is responsible for the delivery of mandated child protection services for all children. First Nation child and family services in Prince Edward Island focuses on prevention, early intervention and gauging the children's results to determine the real impact of services on children's lives. In the late 1990s, the Prince Edward Island Director of Child Welfare and Lennox Island First Nation developed a prevention program that emphasized the importance of safeguarding the culture and identity of Aboriginal children. In August 2009, Prince Edward Island's First Nations entered into a partnership with AANDC and the provincial government to implement an Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach to deliver child and family services. The framework agreement will provide $1.7 million in new funding over five years.

Pivotal to the development of the Mi'kmaq Family PRIDE Program is the belief that children, families and communities benefit most from services that are sensitive to and congruent with their cultural beliefs and traditional values. The PRIDE vision is: To provide a holistic and culturally sensitive approach to individual, family and community wellness and risk reduction through prevention services and protection support. The PRIDE's ten objectives are:Footnote 13

- Promote the sacred value and inherent worth of children;

- Reinforce the traditional cultural values of caring, sharing and co-operation within the community as a whole to ensure the well-being of children and their families;

- Respect the dignity and independence of children and adults, and their right to participate in decisions that affect their lives;

- Assist parents, extended family and community to raise healthy, happy, resilient children;

- Reinforce the linkage between children who are ordinarily resident on reserve and who are being cared for outside their communities with their Mi'kmaq heritage, advocating and supporting a continued relationship with their immediate and extended family, culture, and community;

- Promote and reinforce cultural pride in children and youth;

- Strengthen supportive networks and collaborative decision making within the community, and amongst the community and external service providers;

- Promote the best interests of children with regard at all times for their safety and well-being;

- Reinforce the value of parents and parenting, and the role of the community in supporting parents; and

- Strengthen families and community life.

The Prince Edward Island First Nation prevention system currently in place under the EPFA focuses on individual, family and community well-being and risk reduction through three types of preventive interventions:

Primary prevention

- Focuses on the entire community and promotes individual, family and community wellness, including positive self-esteem, cultural pride, positive parenting, etc. Public awareness and community education initiatives are paramount.

- Seeks to strengthen or increase the well-being of whole communities so that children grow up in safe, healthy environments.

Secondary prevention

- Focuses on "at-risk" children and parents, including sectors of the community such as substance abusers, children raised in substance abusing families, youth at risk of suicide, single teen moms, etc.

- Provides a strengths-based approach to risk reduction and enhancing positive functioning.

- Examples of secondary prevention include parenting supports, talking circles for adults and children, and self-esteem and independent living workshops for children and youth.

Tertiary prevention

- Focuses on children who have been abused or neglected, and families in which abuse/neglect is occurring.

- Seeks to prevent further abuse from occurring in order to prevent other family problems and trauma from having future or long-term implications for children.

- Examples of tertiary prevention include traditional and contemporary counselling for children and their families and, sometimes, out-of-home care for children until such time as the families have been strengthened, the communities have been transformed and the children are no longer at risk of harm.

1.2.6 Financial Resources under EPFA in Quebec and Prince Edward Island

The EPFA implements three funding streams: maintenance, operations and prevention services.

- Maintenance is budgeted annually based on actual expenditures of the previous year.

- Operations and prevention services funding are based on a cost model developed at regional tripartite tables and are consistent with reasonable comparability to the respective province within AANDC's program authority.

- Funding under the three streams is eligible for movement from one stream to another in order to address needs and circumstances of individual communities.

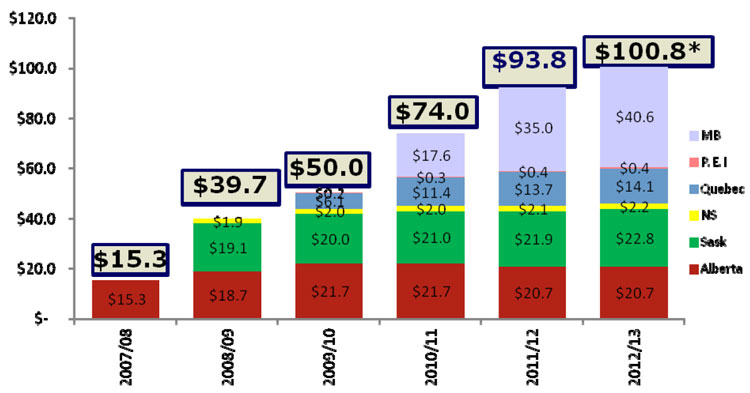

Table 3 below provides an overview of the amount of EPFA funding in the two provinces (in millions of dollars).

| 2007-08 | 2008–09 | 2009–10 | 2010–11 | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013-14 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | $15.30 | $18.70 | $21.70 | $21.70 | $20.70 | $20.70 | $20.70 | $139.50 |

| Saskatchewan | $19.10 | $20.00 | $21.00 | $21.90 | $22.80 | $22.80 | $127.60 | |

| Nova Scotia | $1.90 | $2.00 | $2.00 | $2.10 | $2.20 | $2.20 | $12.40 | |

| Quebec | $5.90 | $12.20 | $13.50 | $13.90 | $14.30 | $59.80 | ||

| Prince Edward Island | $0.20 | $0.30 | $0.40 | $0.40 | $0.40 | $1.70 | ||

| Manitoba | $17.60 | $15.00 | $40.60 | $41.70 | $114.90 | |||

| TOTAL | $15.30 | $39.70 | $50.00 | $75.00 | $73.80 | $100.80 | $102.30 | $456.90 |

2. Methodology

2.1 Scope

The evaluation examined the implementation of the EPFA in Quebec and Prince Edward Island from 2009-10 to 2012-13. Data was collected between January 2013 and August 2013. The objective of the evaluation is to determine whether the design and implementation of the program is adequate for it to fulfill its intended objective. First Nation and Inuit communities that belong to the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement are funded for health and social services through separate mechanisms external to the FNCFS Program, thus were not included in this evaluation.

Previous Evaluations

The Implementation Evaluation of the EPFA in AlbertaFootnote 14 found that the prevention approach is responsive to community needs and that overall it offers a culturally appropriate model for First Nation communities in the province. While the evaluation showed some preliminary evidence of success from implementing the approach, there were jurisdictional challenges, as well as concerns with human resource shortages, salaries, support from government/agency management, community linkages, and geographical isolation.

This report was followed by the Mid-Term National Review in 2010-2011, which examined the overall relevance of the EPFA, promising practices in prevention programming, as well as insights on the development of additional tripartite frameworks. The review reiterated the need for a prevention approach given the over-representation of children in care, common underlying risk factors in First Nation communities and service delivery issues. The report also examined factors that served to help or hinder EPFA framework agreements and best practices in prevention programming.

Finally, the 2013 EPFA Evaluation in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia confirmed the need for a preventive approach in both jurisdictions. In both provinces, the report found an increase in prevention activities and evidence to suggest that the EPFA was supporting the security and well-being of children and families on reserve. However, the report also indicated that FNCFS agencies were having challenges with human resources, meeting provincial standards and geographic isolation. Performance monitoring and reporting concerns were also raised.

2.2 Evaluation questions

The Implementation Evaluation of EPFA in Quebec and Prince Edward Island for the FNCFS Program addresses the Treasury Board Secretariat’s Policy on Evaluation by examining value for money through the core evaluation issues of continued need, alignment with government priorities, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities, achievement of expected outcomes, and demonstration of efficiency and economy. As this is an implementation evaluation, a specific focus was put on the design and delivery of the program and how it may contribute toward expected outcomes.

2.2.1 Relevance

The evaluation incorporated findings from previous evaluations of the EPFA to answer some of the questions related to the relevance of the approach. Lines of evidence further examined the relevance of the program in Quebec and Prince Edward Island specifically.

- What are the child welfare and prevention needs of First Nations in Quebec and Prince Edward Island?

- Can the EPFA be reasonably expected to achieve its stated objectives?

- Is there a legitimate, appropriate, and necessary role for the Department and Government of Canada in meeting this need?

- Are there other programs involved in similar activities and do they share the same objectives?

- Is there duplication with other programs’ activities?

- Is the federal role appropriate in the context of other organizations’ roles?

2.2.2 Design and Delivery

The analysis examined the implementation of the approach in each province respectively, how EPFA activities could logically contribute to expected results, how the design and delivery of EPFA contributes to the achievement of outcomes in practice, and factors that facilitated or hindered results.

- To what extent are the prevention activities logically linked to the production of the expected outputs and results?

- To what extent has the design and delivery of the EPFA facilitated the achievement of outcomes and its overall effectiveness?

- Has the approach been implemented as planned? If not, why?

- Is the management / governance of the EPFA effective or are there improvements that could be made?

- To what extent are the monitoring and reporting mechanisms of the prevention approach effective in supporting decision making?

- To what extent has the EPFA influenced the constructive engagement and collaborative networks to improve child welfare?

- What are the key factors that have facilitated or hindered the achievement of results?

2.2.3 Performance (Effectiveness, efficiency and economy)

The evaluation examined early progress toward intended outcomes, recognizing that the impact of preventative programs often takes many years to measure. The evaluation focussed primarily on immediate and intermediate outcomes. It also examined whether the approach is the most efficient and economic way to achieve outputs and outcomes.

- To what extent has progress towards intended outcomes been achieved as a result of the EPFA?

- Have there been positive or negative unintended outcomes? If so, were any actions taken to benefit from or remedy the unintended outcomes?

- Is the current approach the most economic and efficient means of achieving the intended objectives?

- Are there more economic / efficient alternatives for achieving the same outcomes?

2.3 Methodology

As per the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) Engagement Policy, an Advisory Group was convened to obtain feedback on key pieces of the evaluation including the methodology report and the evaluation findings. The working group members included AANDC staff from headquarters and both regional offices, provincial representatives, and First Nation Child and Family Service agency representatives from both provinces. Meetings and exchanges were held with some representatives to provide feedback on methodology, data collection, and findings on an as needed basis.

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence to examine the research questions, resulting in a triangulation of all lines of evidence for the findings. A detailed explanation of the methods is provided below:

Document Review

A comprehensive document review was conducted as part of the Mid-Term National Review of EPFA in 2010-11. For this evaluation, additional documents related specifically to the EPFA in Quebec and Prince Edward Island were reviewed. These included policy and program documents, business plans, recent audits, reviews, and evaluation reports. Documents were read and analyzed based on the evaluation questions and themes.

Literature Review

A review of domestic and international literature was undertaken to examine the need for FNCFS (particularly prevention services for First Nations in Quebec and Prince Edward Island). Specifically, the literature review examined prevention theory, risk factors that necessitate the EPFA, and best practices. Documents were read and analyzed and an account of supporting themes and insights were noted. Findings from the literature review were triangulated with the information retrieved from other lines of evidence.

Key Informant Interviews

Thirty-two interviews were conducted with key program stakeholders to gain an understanding of the perceptions and opinions of individuals who have had a significant role or experience related to EPFA. Interviews were crucial to understanding the implementation of the program in communities and the early achievement of results. Interviewees included the following interview groups: AANDC FNCFS officials (four); FNCFS agency directors and staff (21); and provincial representatives (seven).

Interviews were semi-structured and conducted in-person or by telephone. Detailed notes were taken during the interviews. They were transcribed and analyzed according to research themes. The confidentiality of interviewees was maintained throughout the evaluation.

Case Studies

Case studies were conducted to gather community-level data on the implementation and performance of the EPFA in Quebec and Prince Edward Island. Three case studies were completed (two in Quebec and one in Prince Edward Island). The case studies focused on the FNCFS agencies and the communities that they serve. A total of four communities were visited. In Prince Edward Island, the Lennox Island and Scotchfort communities (one of Abegweit First Nations three reserves) were visited; and in Quebec, the Mashteuiatsh and Gesgapegiag communities were visited. These case studies were conducted to:

- Provide an in-depth look at implementation and performance.

- Examine program outcomes in communities along with the factors that have facilitated or hindered program success.

- Identify promising practices and lessons learned from front-line workers and community members (and potentially from children and families involved with the services).

Case studies did not examine the performance of the specific agency. Instead, they examined agencies as part of the larger implementation of the program.

EPMRB contracted Johnston Research Inc., an independent, Aboriginal-owned and experienced firm, to conduct the case studies. Johnston Research Inc.staff, accompanied and supported by EPMRB staff, visited communities to conduct interviews, observe the community and facilities, and conduct focus groups.

| Case Study Data Collection Method | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Prince Edward Island Communities | |

| Interviews | 18 |

| Focus Groups | 22 |

| On-Site Observations | 2 |

| Quebec Communities | |

| Interviews | 17 |

| Focus Groups | 17 |

| On-Site Observations | 3 |

Finally, two site visits were conducted in Quebec (Wendake and Kitigan Zibi) to conduct interviews and site observations, and to obtain documents from two additional FNCFS agencies.

Surveys

Surveys were administered to agency directors and front-line FNCFS agency staff in Quebec. The surveys were not administered in Prince Edward Island, given that all First Nation communities in Prince Edward Island are served by Mi’kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island and were covered extensively in the case studies. The surveys were used as a quantitative line of evidence to validate findings of other qualitative methods. They were distributed to 15 agencies and were competed by14 staff members from nine of the agencies. It is noted that given the total sample and response, the surveys could not be used for any statistical inference. Rather, they provided more in-depth information from multiple sources in each agency.

The survey examined respondents’ opinions on the implementation of the EPFA, observations at the community-level on the impact of transitioning towards an enhanced prevention focused approach, feedback on partnership building and the development of a continuum of care, as well as notes on promising practices and lessons learned.

2.3.1 Considerations, strengths and limitations

Strengths

- Strengths include the extensive cooperation, which the evaluation team received from the First Nations in Quebec and Prince Edward Island that participated in the evaluation. The First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission also played a key role by providing documents and knowledge on the prevention approach in Quebec. Lastly, the AANDC Quebec regional office was instrumental in helping to coordinate the fieldwork

- This evaluation benefitted from the knowledge of Johnston Research Inc., an Aboriginal firm with extensive expertise in data collection and analysis techniques for collecting and using opinion data and in the use of Aboriginal traditional and contemporary knowledge. As a result, the case studies included the opinions of some of the parents and youth who received support from the EPFA.

Limitations

- As "prevention" is a broad term, and not easily quantifiable, there may be successes that cannot be captured by the evaluation, as they could be based on the development of trust between hard-to-reach families and a prevention worker, or the gradual uptake of new parenting skills.

- The evaluation was limited to visiting six communities. The evaluation would have benefited from visiting more communities to observe directly how the implementation was progressing and to engage with community members who access the services. As a result, a large part of the findings of this evaluation is based on interviews and surveys with service providers. Nonetheless, the evaluators attempted to offset this shortcoming through triangulating interview findings with the document and literature review.

2.4 Roles, responsibilities and quality assurance

EPMRB of AANDC’s Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB’s Engagement Policy and Quality Assurance Strategy. The Quality Assurance Strategy is applied at all stages of the Department’s evaluation and review projects, and includes a full set of standards, measures, guides and templates intended to enhance the quality of EPMRB’s work.

An Evaluation Advisory Committee was established for the purpose of this evaluation and included representatives from EPMRB and the Child and Families Directorate at AANDC Headquarters, AANDC regional offices, provincial representatives, and FNCFS agency representatives. The purpose of the committee was to ensure that results are based on reliable and defendable evidence, anchored in appropriate methodology, and that issues are consistent with Treasury Board Secretariat policies and guidelines.

The majority of the work for this evaluation was completed by EPMRB staff, with the assistance of a consultant for the case studies. Oversight of daily activities was the responsibility of the EPMRB evaluation team, headed by a Senior Evaluation Manager. The methodology and draft final reports were peer reviewed by EPMRB for quality assurance; these reports and a key findings deck were also sent to the Advisory Committee for feedback.

3. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

The key findings regarding the relevance of the EPFA focus on its continued need, its alignment with government priorities, and its alignment with the roles and responsibilities of the federal government.

3.1 Continued need for the EPFA

Finding 1: A prevention focused approach is needed in light of the fact that First Nations, particularly children, are vulnerable to neglect and abuse and further, protection alone cannot resolve all the pressing social issues in First Nations communities across Quebec and Prince Edward Island, where risk factors (e.g. poverty) are prevalent.

The stated objective of the FNCFS Program is to ensure the safety and well-being of First Nations children on reserve by supporting culturally appropriate prevention services for First Nations children and families, in accordance with the legislation and standards of the province or territory of residence. The expected outcome for the FNCFS EPFA Program is to have a more secure and stable family environment for children ordinarily resident on reserve.

Federal activities like the EPFA need to be understood and analyzed in the context of an increasingly complex environment. According to the World Health Organization and International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, child abuse or maltreatment is a serious problem around the world [Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2006.]. Child abuse can be defined in several ways, including any act or series of acts of commission or omission by a parent, caregiver, community or society that results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child.

Canada is no exception, particularly in the case of Aboriginal children where Aboriginal people are dealing with serious psychosocial problems (MacMillan, MacMillan, Offord & Dingle, 1996). The suicide rate in First Nation communities, for example, is twice as high as that of Canada's general population while Aboriginal youth, aged 10 to 29 who live on reserves are five to six times more likely to die by suicide than their counterparts in the rest of the country (Kirmayer et al., 2007). Moreover, Shannon Brennan (2011), notes that in 2009, Aboriginal women were still facing abuse and were nearly three times more likely than non-Aboriginal women to report being victims of violent crime.

Other information also point to a continued need for the EPFA. Statistics from Public Safety Canada's "A Statistical Snapshot of Youth at Risk and Youth Offending in Canada," published in 2012 show that 9,815 Aboriginal youths aged 12 to 17 were accused (charged or otherwise) in 2004 with a criminal offence on reserve. According to the Public Safety Canada statistics, this rate (24,391 per 100,000 youth) is more than three times higher than the average in the rest of Canada (7,023 per 100,000 youth). Also in 2004, the statistics note that young offenders were accused of committing homicides on reserves at about 11 times the rate of young people who were similarly accused elsewhere in Canada, and were seven times more likely to be accused of break and enter and disturbing the peace. While the issue of youth crime is recognized as a concern for many communities across Canada, Public Safety Canada is careful to note that "there is no single source of information to determine the number of youths who commit crimes in Canada," adding that "estimates can be obtained using various methods (e.g., self-reports, official records of convictions, charges, victimization surveys), each providing a slightly different picture of the phenomenon."

In Quebec, 77.4 percent of Aboriginal students begin high school at least one year behind. According to recent Statistics Canada data, in 2010-11, 27 percent of all adults in both provincial and territorial custody, and 20 percent of those in federal custody were Aboriginal people; in other words, this is approximately seven or eight times higher than the proportion of Aboriginal people (three percent) in the adult population as a whole, (Statistics Canada, 2012a.). This is confirmed by the 2011 Annual Report of the Corrections and Conditional Release Statistical Overview, which reveals that Aboriginal people continue to be overrepresented in the justice system and shows that the number of Aboriginal offenders continues to increase.

The ongoing need of the EPFA is further compounded by the observation that early alcohol consumption and drug use is an acute social problem on reserves (Adrian, Layne & Williams, 1990; Gfellner & Hundleby, 1995). Kendall and Kessler (2002), Liddle, Rowe, Dakof, Ungaro and Henderson, (2004) and Kirby and Keon (2004) show that prevention is a key strategy for slowing the progression and reducing the seriousness of at-risk behaviour (alcohol and drug use) and for mitigating or eliminating the psychosocial consequences that can disrupt educational, professional and social development among youth.

Studies show that anxiety, depression, aggression, conduct disorder, delinquency, anti social behavior, substance abuse, partner violence, teenage pregnancy, post traumatic stress disorder, and suicide are among the emotional and behavioral problems associated with abuse (Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Williamson DF. Exposure to abuse, neglect and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children. Violence and Victims 2002; 17(1):3–17).

The preceding is not exhaustive, as several other factors contribute to the need of the EPFA and show that the problem is not limited only to child neglect and abuse and/or the removal of children from the parental home (leading to unstable families). Such persistent underlying conditions, structural factors, or social determinants that contribute to child maltreatment and neglect, continue to exist in Aboriginal communities and enhance the continued need for the EPFA. However, the evaluation is careful to note that while the EPFA has neither the authority nor the capacity to either address or resolve all these issues directly, so far as these conditions prevail, the EPFA will continue to be needed.

Determining factors

Certain key determining factors point to the fact that the need for prevention activities is more profound amongst First Nations. A comprehensive review of the literature on child and family abuse concludes that there is an ongoing need for culturally relevant prevention services for First Nations in Quebec and Prince Edward Island. Key risk factors (with various causes) that contribute to the crucial need for the EPFA among First Nation communities are linked together by the literature, and include emotional, behavioral, family and social problems, which can be divided into four factors: (1) individual; (2) family; (3) social; and (4) background factors.

Individual factors: these are psychobiological in nature (e.g. depression, mental illness and anxiety), and have a decisive influence on an individual's behaviour.

Family factors: refer to detrimental cultural and family circumstances. It includes family breakdown, improper parental behaviour towards children, and the risk that children, particularly boys, will replicate their parents' behaviour. Interviewees mentioned that the intergenerational impacts of residential school have limited their people's ability to learn parental and community skills and responsibilities through their cultural as well as the usual socialization processes.

Social factors: include socioeconomic determinants such as poverty, lack of education, limited employment opportunities, the poor state of housing and sanitation facilities, and poor water quality, all of which affect many Aboriginal people. In 2001, more than half (52.1 percent) lived in poverty, and according to interviewees, living in such conditions incessantly contributes to a feeling of helplessness and hopelessness. Documents reviewed show that in Canada, 40 percent of Aboriginal children are presently living in poverty, compared to 17 percent for the rest of Canada. For example, a review of literature from D. Macdonald & Daniel Wilson (2013) shows that poverty in itself is nothing; however, it carries a heavy symbolic load in our capitalist world. In the case of the EPFA, poverty translates into a lack of resources, power, voice and access to services and raises the need for an ongoing maintenance of the EPFA, if its outcomes are to be realized.

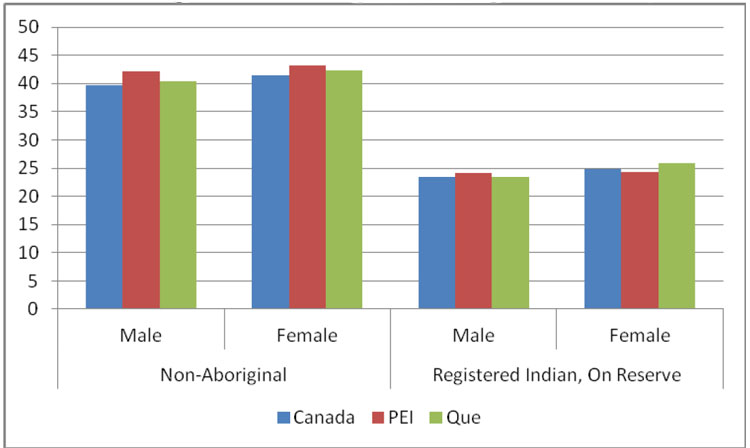

Table 4 shows that the Aboriginal and Registered Indian populations have weaker participation rates in the economy compared to the non-Aboriginal population and, that unemployment rates are more than double for Registered Indians compared to the non-Aboriginal population (with the exception of Registered Indians off reserve in Prince Edward Island, due to small numbers).

| Participation* rate % | Unemployment rate % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Canada | Aboriginal population | Total | 76.3 | 67.6 | 14.4 | 11.2 |

| Registered Indian | On reserve | 63.1 | 57 | 26.1 | 17.5 | |

| Off reserve | 78.4 | 65.6 | 15.2 | 13.2 | ||

| Non-Aboriginal population | Total | 85.6 | 75.8 | 6.2 | 5.8 | |

| PEI | Aboriginal population | Total | 79.3 | 76 | 19.2 | 10.5 |

| Registered Indian | On reserve | 88.9 | 80 | 25 | 18.8 | |

| Off reserve | 68 | 61.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Non-Aboriginal population | Total | 87.6 | 80.5 | 10.1 | 10 | |

| Quebec | Aboriginal population | Total | 75.9 | 69.8 | 13.9 | 9.7 |

| Registered Indian | On reserve | 71.2 | 66.7 | 25.1 | 14.7 | |

| Off reserve | 77.9 | 67.5 | 11.3 | 9.9 | ||

| Non-Aboriginal population | Total | 84 | 75.1 | 6.7 | 5.4 | |

|

Table 1 Source: Statistics Canada, 2011 NHS, AANDC Special Tabulations |

||||||

With respect to education, Table 5 shows the Educational Attainment for the 25-64 age cohort. The non-Aboriginal population, and off- reserve Registered Indians, are more likely to have a post-secondary education than Registered Indians on reserve.

| No certificate,diploma or degree | High school certificate or equivalent | Post-secondary certificate, diploma or degree | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Canada | Aboriginal | Total | 31.81% | 26.26% | 22.43% | 23.06% | 45.76% | 50.67% |

| Registered Indian | On reserve | 50.12% | 42.97% | 16.59% | 19.69% | 33.30% | 37.34% | |

| Off reserve | 29.06% | 25.49% | 24.83% | 22.88% | 46.10% | 51.63% | ||

| Non-Aboriginal | Total | 13.13% | 11.04% | 22.82% | 23.65% | 64.04% | 65.31% | |

| PEI | Aboriginal | Total | 25.00% | 32.00% | 20.65% | 21.60% | 53.26% | 47.20% |

| Registered Indian | On reserve | 33.33% | 25.00% | 11.11% | 30.00% | 55.56% | 50.00% | |

| Off reserve | 0.00% | 30.56% | 20.00% | 8.33% | 72.00% | 58.33% | ||

| Non-Aboriginal | Total | 18.18% | 10.04% | 24.75% | 23.71% | 57.07% | 66.25% | |

| Quebec | Aboriginal | Total | 30.82% | 28.26% | 15.90% | 18.28% | 53.28% | 53.45% |

| Registered Indian | On reserve | 48.15% | 44.55% | 9.35% | 12.81% | 42.44% | 42.59% | |

| Off reserve | 21.83% | 22.51% | 20.36% | 19.10% | 57.89% | 58.38% | ||

| Non-Aboriginal | Total | 15.68% | 13.40% | 18.63% | 20.48% | 65.69% | 66.13% | |

Table 1 Source: Statistics Canada, 2011 NHS, AANDC Special Tabulations |

||||||||

Table 6 shows that in both Quebec and Prince Edward Island, Registered or Treaty Indians on reserve have lower median incomes than other population groups in Quebec and Prince Edward Island. In Prince Edward Island, Registered or Treaty Indians on reserve have a median income of $20,000 compared to $27,600 for Registered or Treaty Indians off reserve, and $34,400 for non-Aboriginal people in Prince Edward Island. In both comparisons, those living on reserve have lower incomes than other population groups in Prince Edward Island. In Quebec, the situation is similar, as Registered or Treaty Indians on reserve have a median income of $23,900 compared to $30,000 for those living off reserve, and the gap widens further when compared to non-Aboriginal people in Quebec who have a median income of $35,300.

| Total** | In the labour force | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | ||||

| Aboriginal population | Total | Total - Sex | $27,511 | $35,594 |

| Male | $31,314 | $39,130 | ||

| Female | $25,044 | $32,894 | ||