Implementation Evaluation of the Nutrition North Canada Program

Final Report

Date : September 2013

Project Number: 1570-7/12023

PDF Version (418 Kb, 67 Pages)

Table of contents

- Glossary of Terms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Design and Delivery

- 5. Evaluation Findings -Performance (Achievement of Immediate Outcomes)

- 6. Evaluation Findings - Effectiveness (Efficiency and Economy)

- 7. Evaluation Findings - Best Practices

- 8. Conclusions and Recommendations

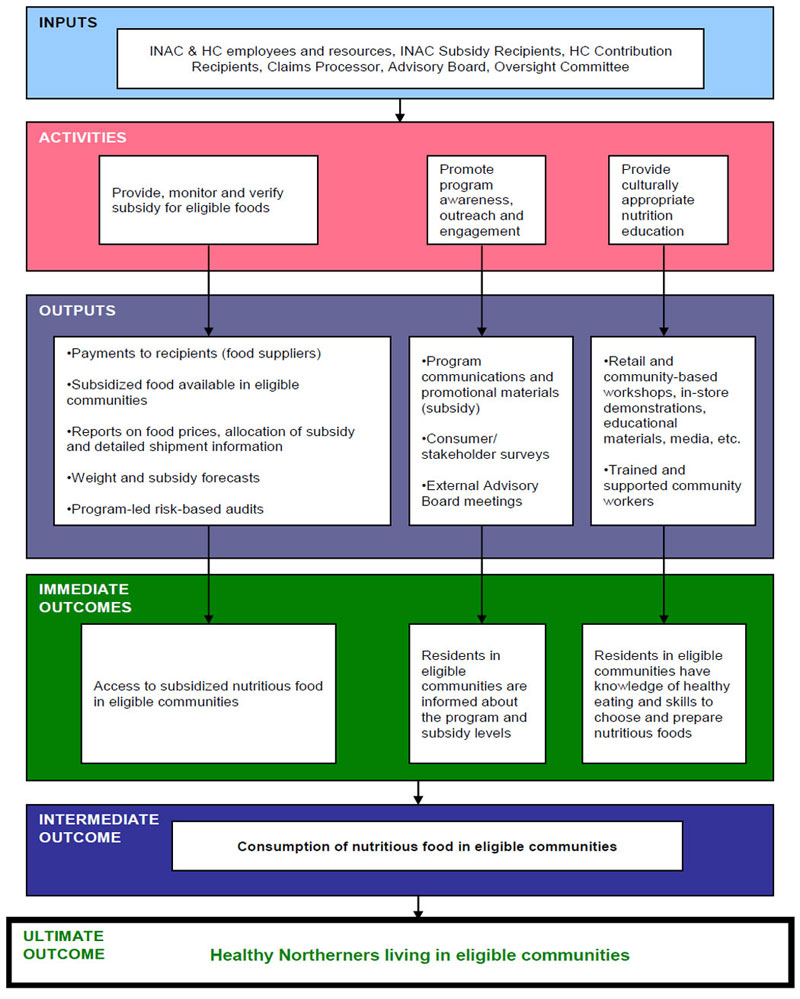

- Appendix A - NNC Logic Model

- Appendix B - Community Profiles

Glossary of Terms

Advisory Board for Nutrition North Canada – A group of individuals whose role is to represent the perspectives and interests of northern residents and communities and to advise the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (AANDC) to help guide the management, direction, and activities of the Nutrition North Canada Program.

Commercially prepared foods – Foods that are prepared and distributed by food manufacturers and which individuals typically buy in a store. These foods can be fresh, frozen, raw or cooked and are usually pre-packaged.

Community eligibility list – A list of isolated communities, which are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Program. These communities lack year-round access to surface transportation.

Country foods (traditional foods) – Foods obtained through local hunting, fishing or harvesting activities. Examples include caribou, ptarmigan, seal, Arctic char, shellfish and berries.

Direct or Personal orders – A provision under the Nutrition North Canada Program that gives individuals and certain institutions (e.g. schools, daycares) in eligible communities access to the program's subsidy when they buy eligible items directly from a supplier in the South that is registered with the program. Direct orders made by individuals are often referred to as "personal orders."

Northern retailers (also see Southern suppliers) – Retailers who operate stores located in communities that are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Program and who sell foods that are eligible under the program. These retailers are registered as a business with the Canada Revenue Agency and have an agreement with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (AANDC) to govern the funds (the subsidy) they receive under the Nutrition North Canada Program.

Non-food items – Products that are eligible for a subsidy in Old Crow, Yukon, under the Nutrition North Canada Program. Examples of eligible non-food items include diapers, toilet paper and toothpaste.

Non-perishable foods – Foods which do not spoil quickly when stored at room temperature. Examples include dry pasta, dehydrated vegetables and canned fruit.

Perishable foods – Foods that are fresh, frozen, refrigerated, or have a shelf life of less than a year. They must be shipped by airFootnote 1.

Point of sale - The place where sales are made. On a macro level, a point of sale may be a mall, market or city. On a micro-level, retailers consider a point of sale to be the area surrounding the counter where customers pay. This is also known as "point of purchase."

Retail subsidy – An amount of money that the federal government transfers under the Nutrition North Canada Program to registered northern retailers and southern suppliers to help reduce the cost of perishable, nutritious foods in eligible isolated, northern communities.

Revised Northern Food Basket – The Revised Northern Food Basket is an example of a nutritious diet for a family of four for one week. The combination of foods in the basket meets most nutrient requirements and food serving recommendations in Canada's Food Guide for the four family members: a man and a woman aged between 31 and 50, and a boy and a girl aged between 9 and 13.

Southern suppliers (also see Northern retailers) - Retailers and wholesalers who operate a business located in Canada but not in a community that is eligible for the Nutrition North Canada Program and who sell foods that are eligible under the program. They are registered as a business with the Canada Revenue Agency and have an agreement with AANDC to govern the funds (the subsidy) they receive under the Nutrition North Canada Program. Southern suppliers provide products that are eligible under the Nutrition North Canada Program to small northern retailers, eligible institutions, establishments and individuals living in an eligible community. Information for Retailers, Country Food Processors and Suppliers.

Subsidized foods list – A list of the types of foods which are eligible for a subsidy under the Nutrition North Canada Program.

Executive Summary

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook an implementation evaluation of the Nutrition North Canada (NNC) Program.

Nutrition North Canada was launched in April 2011 and replaced the Food Mail Program. It is a market-driven food subsidy program that seeks to improve access to perishable healthy food in eligible isolated northern communities. By making nutritious food more accessible and more affordable, the program seeks to increase the consumption of nutritious foods and contribute to improving the overall health of the population, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, living in the North.

The NNC Program is a Sub-Program Activity of the Northern Governance and People Program Activity, which contributes to The North Strategic Outcome. The NNC contributes to the Department's strategic outcome area of the North through its expected outcomes of self reliance, prosperity and well-being for the people and communities of the North.

Nutrition North Canada has a fixed budget of $60 million in program funding. Of this, $53.9 million is allocated for the subsidy component through funding agreements with eligible recipients managed by AANDC. AANDC also receives another $3.4 million for program operations. The remaining $2.9 million is for contribution funding the Health Canada nutrition education initiatives component of the program.

This evaluation responds to the Treasury Board requirement to inform AANDC management on the transition from Food Mail to NNC, as well as resource utilization and preliminary results and overall performance. The evaluation is in compliance with requirements from Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation. It does not evaluate outcomes related to the Health Canada component of the program. Results of this evaluation will inform an impact evaluation that is currently being planned for fiscal year 2014-2015.

This evaluation examines issues related to relevance and performance (achievement of expected outcomes and efficiency and economy). Special attention was paid to issues related to design and delivery and best practices/lessons learned. The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence to respond to the evaluation issues and questions, including a document review, literature review, a review of program data, key informant interviews and case studies. Data collection and analysis were conducted between January 2013 and August 2013, with visits to four communities currently eligible from the NNC Program.

EPMRB was the project authority for this evaluation and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process and in keeping with the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation. The majority of the evaluation work was completed by the EPMRB team, with the assistance of Rick Gill of Alderson-Gill & Associates for a portion of the case studies. An evaluation working group, including AANDC program and, to a lesser extent, Health Canada, was formed in order to provide knowledge and expertise. Representatives from Aboriginal organizations, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Assembly of First Nations, contributed to the working group as resource representatives.

The evaluation makes the following key findings/conclusions:

With respect to relevance:

- There is a continued need for NNC to increase access to healthy foods, including country foods, for residents of isolated northern communities;

- NNC is clearly aligned to Government of Canada's priority of supporting healthy outcomes for Canadians; and

- NNC is clearly aligned with the roles and responsibilities of the federal government in supporting healthy outcomes in the North. While evidence of other food subsidy or healthy food programming was found at other levels of government, these programs were generally found to be complementary to NNC, rather than duplicative. At the same time, there appears to be a food policy framework that is fragmented across federal, provincial and local jurisdictions.

With respect to program design: - NNC Program supply-chain model is well-suited to achieving program objectives of making food more accessible;

- Program eligibility criteria is preventing some fly-in communities from participating in the program resulting in an under-addressed need in those communities;

- The transition from Food Mail to NNC was facilitated by the decision to expand the list of eligible products for a period of 18 months. Since the completion of the transition period, it is not clear whether processes in place for ensuring review and policy discussion on the food eligibility lists are being fully realized;

- There is a need for the program design to better support the program's objective of supporting the consumption of country foods;

- Roles and responsibilities of AANDC and Health Canada are clear, however, communication efforts between departments could be improved;

- The role of the Advisory Board and the Oversight Committee should be more clearly defined; and

- Data collection and reporting procedures are in place for ongoing performance measurement; however, improvements should be made to data collection for measuring performance at the higher outcome level.

With respect to performance: - An increase in the access to nutritious food can be demonstrated clearly through program documents and shipment of food. There is still concern that the availability and affordability of food in general, remains problematic;

- Program communications activities have facilitated discussion and engagement around food issues but less understanding of how the program works. Further, the extent to which the subsidy is being passed on was identified as not always being clear to consumers, suggesting a greater need for transparency on retailer's pricing before and after the application of the subsidy;

- NNC is seen to be reaching a larger proportion of the at-risk northern population than Food Mail as emphasis is placed on the use of the retail store and less emphasis on the use of making direct or personal orders;

- Nutrition education initiatives, including retail and community-based activities, were identified as being essential in achieving the ultimate outcome of the program;

- Weather, capacity and infrastructure issues have the potential to be major hindrances to transportation in the North; and

- The high cost of hunting, trapping and fishing, along with limited knowledge of healthy food preparation, has led many northern shoppers to turn to less-nutritious food options.

With respect to cost-effectiveness: - NNC has improved cost-effectiveness largely through its market-driven model and revised subsidized foods list;

- Community-led food initiatives and investments in infrastructural capacity have the potential to decrease program costs while supporting eligible communities from within;

- Although NNC's subsidy budget has been able to support eligible communities thus far, with increased demand for the program, the capped budget may not be sufficient to support access to nutritious food; and

- The cost containment strategy has not been fully implemented.

It is recommended that AANDC:

- Review community eligibility criteria to ensure that it reflects NNC program objectives.

- Review current governance structures in order to:

- clarify the purpose, role and responsibilities to ensure for an effective Oversight Committee; and

- clarify the purpose, role and responsibilities of Advisory Board, taking into consideration the level of resources required on the part of program management to support those activities.

- Review current communication strategy in order to better coordinate NNC-related program communication and activities between AANDC and Health Canada.

- Continue to develop data collection systems and tools in support of ongoing performance measurement, to support the program's collection of data on longer-term outcomes.

- Coordinate departmental efforts with provincial and territorial partners to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the respective food subsidy programs in the North.

Management Response / Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Review community eligibility criteria to ensure that it reflects NNC program objectives. | Recommendations on community eligibility based on NNC program objectives will be developed. Key NNC governance bodies (Advisory Board and Oversight Committee) and partners such as Health Canada will be consulted. | Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization | March 2014 |

2. Review current governance structures in order to: a) clarify the purpose, role and responsibilities to ensure for an effective Oversight Committee; and |

a) The purpose, role, and responsibilities of the NNC Oversight Committee will be examined and clarified. | Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization | November 2013 |

| b) clarify the purpose, role and responsibilities of the Advisory Board, taking into consideration the level of resources required on the part of program management to support those activities. | b) The purpose and role and responsibilities of the Advisory Board will be reviewed. | February 2014 | |

| 3. Review the current communication strategy in order to better coordinate NNC-related program communication and activities between AANDC and Health Canada. | A shared communications approach will be developed in the fall of 2013. | Director General, Communications | November 2013 |

| 4. Continue to develop data collection systems and tools in support of ongoing performance measurement, to support the program's collection of data to measure longer-term outcomes | Appropriate tools and systems to collect and analyze trends are being designed and will be implemented. | Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization | March 2014 |

| 5. Coordinate departmental efforts with provincial and territorial partners to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the respective food subsidy programs in the North. | Discussions will be held with willing provinces and territories in order to better coordinate efforts with respect to food subsidy programs in the north. | Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization | March 2015 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed on September 18, 2013, by:

Janet King

ADM, Northern Affairs Organization

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Implementation Evaluation of the Nutrition North Canada Programwere approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on September 19, 2013.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This report presents the findings and recommendations of an implementation evaluation of the Nutrition North Canada (NNC) Program.

The evaluation was conducted in response to the Treasury Board requirement that the program be evaluated in 2012-2013 in order to assess the transition from Food Mail and to inform Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) management on: 1) resource utilization; and 2) preliminary results and overall performance. The evaluation is expected to feed into AANDC' status report to Treasury Board for October 2013. It does not evaluate outcomes related to the Health Canada component of the program.

This evaluation is in compliance with requirements from Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation. As per the Policy on Evaluation, this evaluation examines the five core issues of related to relevance and performance, including:

- continuing need for the program;

- alignment with government priorities;

- consistency with federal roles and responsibilities;

- achievement of expected outcomes; and

- demonstration of efficiency and economy.

Further, as this particular evaluation focuses on the implementation of the NNC, special attention was paid to issues related to design and delivery and best practices/lessons learned.

The results of this evaluation will inform an impact evaluation that is currently being planned for fiscal year 2014-2015. The impact evaluation is expected to focus on the achievement of all NNC outcomes, including those associated with the NNC Program's nutrition education initiatives, managed by Health Canada. The impact evaluation will be a horizontal evaluation that is done jointly with Health Canada.

1.2 Program Profile

Nutrition North Canada operates within a northern geographic, economic, social, and cultural milieu that is significantly different from that found in the South. The program is aimed at individuals living in isolated northern communities that are not accessible year-round by road, rail or marine service. The limited accessibility of these communities contributes to the high cost of food, housing, and fuel. The majority of people living in communities serviced by NNC are Aboriginal people, many of whom are living in difficult circumstances as a consequence of limited educational attainment, high rates of unemployment and/or underemployment, and high rates of poverty (often times depending on social assistance to help make ends meet). The barriers that many Aboriginal people face are the consequence of factors that go beyond education, employment and poverty. There is a long history of social, economic, political and cultural disparities that configure when contextualizing the current circumstance. Many are forced to decide which basic need to spend their money on – food, shelter or clothing. Added to this are high levels of addiction occurring in many northern Aboriginal communities – substance abuse and gambling. The relatively quick transition from a traditional subsistence way of life to participation in the wage economy has compromised the overall health and well-being of individuals and communities. Other challenges related to social and economic factors affect the well-being of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. These factors all collide to create high levels of food insecurity in northern communities.

There are strong cultural differences that exist between northern Aboriginal peoples and southern non-Aboriginal populations. These cultural differences translate into variations in notions of diet, food selection, food preparation, food storage and food gathering. Northern Aboriginal cultures involve sharing and, as such, community members do not typically store food, shop for the week, or shop in bulk. This tradition is rooted in the practices of their ancestors, who were hunters and gatherers and took only what was needed from the land. As a consequence of decreasing trends in country food availability and accessibility, increasing numbers of Aboriginal people are now consuming a diet high in non-traditional foods. The relatively brief transition period from a primarily traditional diet to one heavily dependent on non-traditional foods, means that some Aboriginal people, specifically the Inuit, may not be familiar with how to choose and prepare store-bought foods. The historic and cultural background of northern Aboriginal peoples must be taken into consideration when evaluating the effectiveness and impact of NNC on Northerners.

1.2.1 Background

NNC is a market-driven food subsidy program that seeks to improve access to perishable healthy food in eligible isolated northern communities.

The objective of the NNC is to make healthy foods more accessible and affordable to residents of isolated northern communities. By making nutritious food more accessible and more affordable, the program seeks to increase the consumption of nutritious foods and contribute to improving the overall health of the population, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, living in the North.

NNC replaced the Food Mail Program, which was an airfreight transportation subsidy program operated by Canada Post since the late 1960s.

Population growth and increasing fuel prices were resulting in annual resource shortfalls, which required the program to seek additional funds from the fiscal framework each year. As a result, AANDC was directed by Cabinet to conduct an extensive review of the Food Mail Program and develop options to improve its efficiency in achieving its objectives, while maintaining financial sustainability and predictability.

In Budget 2010, the Government of Canada announced funding for a new program to improve access to affordable healthy food for Northerners. NNC was officially announced on May 21, 2010, as the replacement to the Food Mail Program, and the transition period began.

The NNC Program was launched on April 1st, 2011.

How the NNC Subsidy works

AANDC provides a subsidy directly to northern retailers, suppliers, and country food processors that apply, meet the program's requirements and register with NNC by signing funding agreements with AANDC.

Under NNC, arrangements to ship food to northern isolated communities are managed by three categories of eligible recipients. Eligible recipients include:

- Northern Retailers: Retailers that operate stores located in eligible communities where eligible items are available for purchase;

- Southern Suppliers: Retailers and wholesalers that operate a business located in Canada where eligible items are available for purchase; that sell eligible products to northern retailers, eligible social institutions, establishments and individuals; and

- Northern Country food processors: Federally regulated country food processors/distributors and/or approved-for-export plants located in the North that supply eligible items to eligible communities.

Recipients must possess a Business Number issued by the Canada Revenue Agency, and agree to the terms and conditions of the arrangements to be made with AANDC to govern the transfer of funds (the subsidy).

These recipients claim the subsidy through NNC, based on the weight of eligibleFootnote 2 food shipped by air. When claiming the subsidy, recipients submit invoices and waybills detailing shipment information such as weight by category of eligible items, as well as destination community and recipient (i.e. store, individual, institution).

To assist in processing recipient subsidy claims, AANDC has entered into an agreement with a third party claims processor who is responsible for receiving, reviewing and processing recipient subsidy claims and supporting documentation.

Subsidy payments are made to recipients based on the weight of eligible items shipped to eligible communities. By signing the funding agreements with AANDC, NNC recipients are responsible for passing on the subsidies to their customers; providing proof of the nature of shipments; providing some visibility for the program; and for providing data on products shipped and pricing.

Subsidy rates are set on a per kilogram basis of eligible foods and vary by community. In general, subsidy rates tend to be higher for communities where operating and transportation costs are higher. A majority of the communities receive the full subsidy amount, while the others are eligible for a nominal subsidy.

Foods Eligible for a Subsidy under NNC

Nutrition North Canada subsidizes perishable foods, including country or traditional foods that are commercially-processed in the North.

Perishable foods can be fresh, frozen, refrigerated, or have a shelf life of less than one year. They must be shipped by air. A higher subsidy level applies to the most nutritious perishable foods, including fresh fruit, frozen vegetables, bread, meat, milk and eggs. A lower subsidy level applies to other eligible foods such as flour, crackers, ice cream and combination foods (e.g., pizza, lasagna).

Country or traditional foods (e.g. arctic char, musk-ox, caribou) are eligible for a subsidy under the program. These country foods must either be commercially-processed in the North and shipped by air to eligible communities (under the country food specific subsidy rateFootnote 3), or shipped by plane from the South by a registered retailer or supplier (in this case they are eligible for the same subsidy as other meats). Currently, there are three country food processing facilities in Nunavut that meet the program's requirements: Kitikmeot Foods in Cambridge Bay, Kivalliq Arctic Foods Limited in Rankin Inlet, and Pangnirtung Fisheries Limited in Pangnirtung.

AANDC maintains the list of eligible food items (referred to as the Subsidized Food List) and the list of eligible northern communities and is responsible for posting the lists and subsidy rates on the departmental website.

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The NNC objectives are as follows, as per the program's Performance Measurement Strategy (September 2010):

- Make nutritious food more accessible and more affordable;

- Support the consumption of country foods; and

- Provide nutrition education on healthy foods choices and develop food preparation skills by targeted Health Canada initiatives (led by Health Canada).

The activities undertaken by AANDC and Health Canada are intended to result in the following immediate outcomes identified by the NNC's logic model (see Appendix A) as:

- Access to subsidized nutritious food in eligible communities (led by AANDC);

- Residents in eligible communities are informed about the program and subsidy levels (led by AANDC); and

- Residents in eligible communities have knowledge of healthy eating and skills to choose and prepare nutritious foods (led by Health Canada).

All three of these outcomes lead to the intermediate outcome identified by the NNC's logic model as consumption of nutritious food in eligible communities.

By making nutritious food more accessible and more affordable, the program seeks to increase its consumption and contribute to the ultimate outcome for NNC, which is Healthy Northerners living in eligible communities and ultimately improve the overall health of the population, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, which is a key expected outcome of the Government's Northern Strategy.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

Program Management

Two federal departments have specific responsibilities in implementing this new program: AANDC and Health Canada.

AANDC has overall responsibility for the NNC Program. AANDC is responsible for providing, monitoring and verifying the subsidy for eligible foods and promoting program awareness, outreach and engagement.Footnote 4 The Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization and the Director General, Devolution and Territorial Relations are accountable, through the Deputy Minister, to the Minister for the implementation, management, monitoring and reporting of the food subsidy program. AANDC works with the Communications Branch to promote program awareness, outreach and engagement.

The program staff located at AANDC Headquarters administers the overall delivery of NNC. Their responsibilities include:

- Receiving and processing applications from potential program recipients;

- Managing funding agreements with recipients, including subsidy payments;

- Reviewing food price surveys;

- Identifying options for adjustments to the program's subsidy rates, the list of foods eligible for subsidy and/or the list of communities eligible under the program in order to ensure financial sustainability;

- Monitoring program delivery and outcomes to assess the performance of the program;

- Procuring a third-party Claims Processor and working with them to ensure validity of claim submissions and to process funding payments;

- Working with retailers to ensure visibility (via promotional materials) of the program and of subsidy rates to the consumer;

- Ongoing development and refining of program policy;

- Supporting governance bodies, including outreach activities like public meetings in eligible communities;

- Supporting program communication of the program, including compiling and posting data on the program website, responding to public and stakeholder inquiries and feedback; and

- Responding to information requests, including Access to Information and Privacy.

Health Canada, through its First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, funds complementary nutrition education initiatives in fully-eligible communities in order to support increased knowledge of healthy eating and development of the skills to choose and prepare nutritious foods. Outputs linked to Health Canada's component of the program are retail and community-based activities, such as: nutrition workshops, cooking classes, in-store demonstrations, educational materials, media, etc; and trained and supported community workers. The immediate outcome from Health Canada's activities and outputs is that residents in eligible communities have knowledge of healthy eating and skills to choose and prepare nutritious foods.

In addition to newly funded activities, Health Canada provides an advisory role to AANDC in the selection and approval of eligible food items, as well as providing general expert advice in the area of nutrition.

Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

Key NNC stakeholders include:

- Northern retailers, southern suppliers and country food processors, who are the recipients of the subsidy;

- Aboriginal communities and organizations, and territorial governments who enter into contribution agreement with Health Canada to organize and implement nutrition education activities in support of NNC; and

- Northerners living in eligible communities, the ultimate beneficiaries of the program, who are represented to some extent by the External Advisory Board.

Oversight and Advisory Committees

An external Advisory Board with up to seven members and one technical advisor, was established to represent the perspectives and interests of northern residents and communities in relation to the management and effectiveness of the NNC Program. The members of the Board are selected by the Minister of AANDC in consultation with the Minister of Health and are appointed to a three-year term, renewable on a yearly basis. Board members are chosen based on their overall experience and their ability to expand public awareness, and participate on a voluntary basis, without decision-making power.

The role of the Advisory Board is to draw from the experience and expertise of organizations and individuals involved in transportation, distribution, nutrition, public health, government agencies, community development, retailers, wholesalers and others engaged in the provision of food to northern communities to advise the Minister of AANDC on various matters including, but not exclusive to, program performance, communications and public awareness, health and nutrition strategies, transportation systems, food supply chain management, food pricing, and food eligibility, in terms of the ways in which they are serving the interests of northern residents or could be improved.

The Oversight Committee is comprised of Assistant Deputy Minister and Director General level executives from AANDC, Health Canada and Transport Canada, and Central Agencies (as ex-officio members). It monitors the achievement of program objectives and the effectiveness of cost containment measures. The intention was that they would also provide strategic direction to program managers on program policy and operations matters, as well as approving the subsidy rate schedule.

AANDC chairs the committee and seeks advice from Health Canada on health and nutrition-related issues, from Transport Canada on transportation-related issues such as the impacts of the new program on northern air services, as well as from Treasury Board Secretariat and the Department of Finance on the management of cost containment measures.

1.2.4 Program Data

Documents reviewed show that the following key steps are undertaken in data collection:

- AANDC personnel monitor and verify the subsidy process by collecting and analyzing data on food prices, volumes and shipment content.

- Data is used to support funding forecasts, program and policy reviews and adjustments, including adjustments to the subsidy rates, the list of eligible food and communities, and implementation of cost containment strategies and framework.

- Verification of recipient claims to ensure that funding obligations are being met are carried out by a third party. Outputs resulting from these activities include payments to recipients, subsidized food available for sale in eligible communities, reports on the cost of the Revised Northern Food Basket, allocation of subsidy and detailed shipment information, weight and subsidy forecasts and program-led risk-based compliance reviews.

Further, a Performance Measurement Strategy was approved by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in September 2010.

In January 2011, AANDC developed a control framework to monitor the relationship with third parties (AANDC subsidy recipients and contractors) to ensure neutrality, objectivity and that appropriate controls are in place. Benchmark data was to be collected prior to the launch of the new program in April 2011.

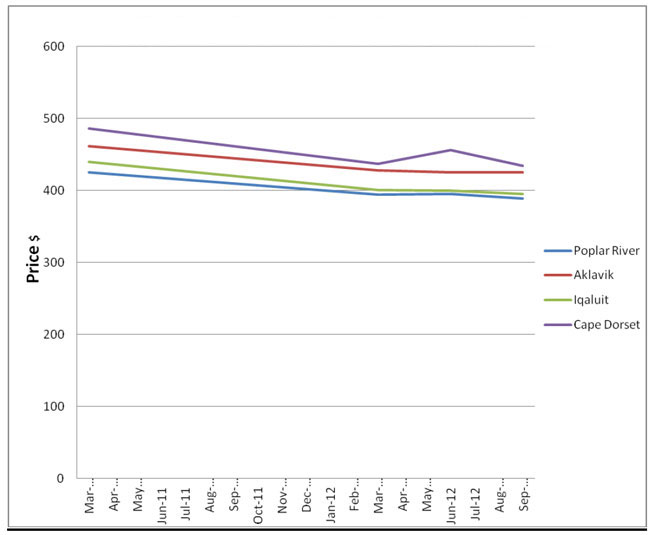

To assist with monitoring and reporting, AANDC collects from its subsidy recipients detailed information on shipments of eligible products (e.g., weight by pre-determined categories, destination community, and for southern suppliers, customer type) and pricing (northern retailers are required to submit the price of items in the Revised Northern Food Basket by community on a monthly basis). These data are used for performance measurement as they translate directly into performance indicators (Tier 1 indicators) for the first stream of program activities, outputs and immediate outcome (i.e., to provide, monitor and verify subsidy for eligible foods so that eligible communities have access to subsidized, nutritious food and commercially produced country food). The quarterly reports on food pricing include the cost for the final month of the quarterly period (ie, June, September, December and March).

To this end, the program's management team created databases and spreadsheets to store data on:

- Food prices for each item in the food basket.

- Shipment volumes on a per-community-basis and per-category basis.

- Subsidies paid out per-period and per-community.

The data collected are used to prepare quarterly, semi-annual and/or annual reports on food basket costs, allocation of subsidy and detailed shipment information; to produce weight and subsidy forecasts; and to target program-led compliance reviews. Additionally, a survey to measure the awareness level and satisfaction level of consumers about the program was planned by AANDC but has not been undertaken. However, AANDC has commissioned a major study of food retailing in the North that is currently being conducted by eNRG research group and the Transport Institute at the University of Manitoba.

1.2.5 Program Resources

Nutrition North Canada has a fixed budget of $60 million in program funding. Of this, $53.9 million is allocated for the subsidy component through funding agreements for eligible recipients managed by AANDC. AANDC also receives another $3.4 million for program operations.

The remaining $2.9 million is for the Health Canada nutrition education initiatives component of the program.

| AANDC | Annual Program Funding |

|---|---|

| Vote 1: personnel, claims processing contract, compliance review contract, Advisory Board support, data collection, marketing / communication material | $3.4M |

| Vote 10: contribution funding | $53.9M |

| Health Canada | |

|---|---|

| Vote 1: community implementation, capacity building, support | $0.3M |

| Vote 10: contribution funding | $2.6M |

| Total | $60.2M |

*Totals may not add up due to rounding |

|

2. Evaluation Methodology

The Terms of Reference, developed during the planning phase of the evaluation, identifies the scope, proposed methodology, key issues and resources for the evaluation.

The Terms of Reference was approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in September 2012.

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation scope included the period related to the transition from the previous Food Mail Program to Nutrition North (fiscal year 2010-2011), and the implementation of the first eighteen months of AANDC's operation undertaken between April 1, 2011, and October 1, 2012.

The evaluation focuses on AANDC commitments as per the program's logic model ( Appendix A). It examines AANDC's activities and outcomes and does not evaluate outcomes related to the Health Canada nutrition education components of the program as these will be evaluated as part of an impact evaluation to be done jointly with Health Canada.

The evaluation was undertaken between September 2012 and August 2013.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The evaluation of Nutrition North Canada is aligned with the Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Evaluation, and triangulates multiple line of evidence and examines the following core evaluation issues:

Relevance

- Is there a continued need for the program? (Continued Need)

- To what extent are program objectives aligned with a) government-wide priorities; and b) are they linked to AANDC's strategic outcomes? (Alignment with government priorities and departmental objectives)

- To what extent are the objectives of the program aligned with the role and the responsibilities of the federal government? (Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities)

- Is there duplication or overlap with other programs, policies or initiatives? (Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities)

Performance – Effectiveness / Success

- To what extent has the NNC Program model created cost-effectiveness in terms of public money invested versus results (affordable food prices, etc.) compared to the former Food Mail Program?

- To what extent has access to subsidized nutritious food in eligible communities changed?

- To what extent are residents in eligible communities informed about the NNC Program and subsidy levels?

- To what extent are residents in eligible communities consuming subsidized nutritious food?

- What factors are facilitating or challenging the achievement of results?

- Has the NNC Program had any unexpected impacts, positive or negative?

- To what extent have the oversight committees and external advisory board been effective?

- To what extent do residents in eligible communities have knowledge about healthy eating and skills to choose and prepare nutritious foods?

Performance – Efficiency and Economy

- What modifications or alternatives might improve the efficiency and economy of the NNC Program?

- How can the NNC's efficiency be improved? Are there opportunities to identify cost saving measures?

- How has the NNC Program optimized its process and quality of services to achieve expected outcomes?

- How can the NNC's efficiency be improved?

Other Evaluation Issues

- Are there best practices and or lessons learned?

Design and Delivery

- To what extent does the program's design facilitate the achievement of results? (including AANDC and Health Canada complementarities of their activities to deliver the program in order to achieve results)

- Are AANDC's and Health Canada's roles and responsibilities in delivering the NNC clear?

- To what extent has the NNC been implemented as planned? (e.g. staffing, level of effort, use of external claims processer)?

- To what extent has the governance structure been implemented as planned?

- Are adequate data collection and reporting procedures in place for performance measurement?

2.3 Evaluation Methods

2.3.1. Planning and Development of Methodology

NNC Evaluation Working Group

Subsequent to the approval of the Terms of Reference, a Working Group was formed.

The purpose of the Working Group was to provide feedback on key pieces of the evaluation, including feedback on the methodology and evaluation findings.

The Working Group included members from AANDC and, to a lesser extent, Health Canada. Representatives from Aboriginal organizations, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Assembly of First Nations, contributed to the working group as resource representatives.

The Working Group met to review and provide feedback on the evaluation methodology prior to data collection. Subsequent meetings and exchanges were held with some representatives on an as needed basis.

Detailed Methodology Report

The development of the methodology for the evaluation was informed primarily by the NNC Performance Measurement Strategy (dated September 2010), which outlines some of the key indicators and information collected and through preliminary consultations with NNC Program management during the development of the evaluation's Terms of and Reference. An initial review of program documentation, a media scan and evaluation team participation in two NNC Advisory Board Meetings and visit to the community of Nain, Labrador was also conducted as part of the planning process.

2.3.3 Data Collection and Analysis Phase

Data collection and analysis was conducted between January 2013 and August 2013, with visits to four communities currently eligible for the NNC Program.

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence to respond to the evaluation issues and questions. A detailed explanation of the methods is provided below:

Literature Review

A review of domestic and international literature was conducted to examine issues of relevance, lessons learned, and best practices. Relevance was examined within the context of key issues related to the NNC Program. Specifically, the evaluation examined factors affecting the need for the program (e.g. food security, access to nutritious foods, food systems, and traditional food harvesting), how the program aligns with government role and priorities, alternative programs that support or contribute to similar outcomes, and best practices for providing nutritious foods to isolated communities.

The literature review began with a systematic scan of reports, documents, and articles using key words and phrases related to NNC. Key documents were identified for review and an index of documents was created. The list of documents was assessed to verify that there were no gaps, ensuring the literature review did not duplicate previous research. Care was taken to ensure previous research conducted for departmental evaluations or reviews was incorporated.

Documents were summarized, analyzed, and coded according to the evaluation questions. Major findings populated a literature review summary template. Common themes and insights as a result of the coding were interpreted and written in a findings summary document that was later triangulated with other lines of evidence.

The review of literature resulted in the identification of an extensive amount of literature relating to need, including the issue of food security and nutrition in remote locations resulting in strong evidence related to relevance. However, the literature review was less able to identify literature related to NNC and its effectiveness as a recently implemented program.

A list of literature reviewed and a findings template that analyzed the evaluation issues identified for the literature review was completed.

Document review

In total, over 80 key documents were reviewed and included, but was not limited to, the following:

- Program and policy related documentation: Memoranda to Cabinet, Treasury Board submissions, strategic plans, annual performance reports, related program evaluation and program audit reports, as well as other documents that make reference to NNC (e.g. documents related to Ministerial Review, speeches from the Throne, federal budgets, legislation, policy statements, etc.), NNC Performance Measurement Strategy, management responses and action plans and follow-ups and documentation related to the Health Canada component of NNC (NNC– Nutrition Education Initiatives Program Framework (2012-2013).

- Documents internal to NNC operations: actual program expenditures, quarterly reports, contribution agreements, list of registered recipients, communication and social media plans, payments made to recipients and the method used to calculate the payments, external compliance reviews and audit reports, level of subsidy by product, list and criteria use to select community and food eligible, cost of food basket and its method to calculate it.

A list of documents reviewed and a findings template that analyzed the evaluation issues identified for the document review was completed.

Media Scan

A media scan of relevant NNC news-related articles was conducted by analyzing press clippings against a framework based on the program's Performance Measurement Strategy. The media scan included articles between January 1, 2011, and September 28, 2012. The media scan provided context and allowed for further refinement of the evaluation issues and questions as well as a line of evidence in the overall analysis.

Data Analysis

The evaluation also included an analysis of quantitative program data, which supports some of the other lines of evidence in the analysis of evaluation issues relating to performance and data- collection and reporting.

The data analysis examined transactions between April 1, 2011, and March 31, 2013. Information was extracted from the NNC database using the following categories:

- Community

- Reporting Category

- Kilograms by subsidy level 1, 2, country food and total

- Subsidy dollars by subsidy level 1, 2, country food and total

Community population was inserted into the database using the 2006 Census. Kilograms and subsidy dollars were calculated into per capitaFootnote 5 values for the purpose of the analysis. The data was then analyzed using SPSS One Way ANOVA with year (2011-12 and 2012-13) as the dependant variable, and with data aggregated by community or food reporting category as independent variables.

This allowed for information to be analysed by average per capita kilograms shipped and subsidy spent by Food Categories in 2011-12 and 2012-13, as well as by the average per capita kilograms shipped and subsidy spent by community in 2011-12 and 2012-13.

In addition, the program's Cost Containment Strategy was identified for review. Documents, such as Treasury Board submissions and Oversight Committee meeting documents, outlining the various cost-saving methods available for the program were examined. Further, data published by NNC, such as kilogram amounts and subsidy amounts for different subsidized items were assessed in order to determine the use of the Cost Containment Strategy. Additional information about this analysis can be found in Section 6.3 of the report.

A technical report that analyzed the evaluation issues identified for the data review was completed.

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews were used to gain a better understanding of perceptions and opinions of individuals who have had a significant role or experience in management and delivery of NNC as well as stakeholders who were expected to benefit from the program.

A total of 34 key informants were interviewed, as broken down by the following interview groups:

- Program Management/Accountability Partners (i.e. Program Administration, Communication, Claims Processers, Health Canada and Transport Canada) [n=14]

- Governance (NNC Advisory Board and NNC Oversight Committee representatives) [n=3]

- External Stakeholders (i.e. Aboriginal Representative Organizations and Provincial/Territorial Representatives) [n=3]

- External Experts [n=3]

- Program Recipients (i.e. Retailers, Wholesalers and Shippers, Country food processors) [n=11]

Interview guides by interview group were designed to address all of the pertinent evaluation issues and questions and were tailored to the different respondent groups within each interview group, as applicable. This allowed for targeted questions that make the best use of the knowledge and experience of each key informant. As much as possible, common questions were applied across the guides to promote rigor and to strengthen the analysis.

All interviewees were sent the finalized guide by email in advance of their scheduled interview to allow for preparation for the interview. Key informants located in the National Capital Region were offered the option of being interviewed in person; most other interviews were conducted via telephone; and some interviews with external stakeholders outside the National Capital Region were conducted during, but separate from, case site visits where possible.

Key informant interview responses were organized, analyzed and coded according to the evaluation questions.

A findings template that analyzed the evaluation issues identified for the document review was completed. Due to the extensive amount of information collected through the key informant interviews, common themes and insights were compiled in a findings summary document that was triangulated with other lines of evidence.

Case Studies

Four case studies were completed in order to obtain various perspectives at the community level.Footnote 6 Issues related to the relevance of the NNC, the transition from the Food Mail Program to the NNC, the effectiveness of the NNC to date, and design and delivery of the program were addressed.

| Iqaluit, Nunavut |

February 2013 |

|---|---|

| Aklavik, Northwest Territories |

February 2013 |

| Cape Dorset, Nunavut |

February 2013 |

| Poplar River, Manitoba |

July 2013 |

Several criteria were used to determine the communities selected: geographic representation, percentage of subsidy expenditures by region, subsidized products by weight per capita, community population and number of food outlets.

The following methods and information sources were used in conducting the case studies:

- File and data review. This was conducted primarily in Ottawa, drawing on any community-specific information in the NNC Program files. This informed researchers on the local grocery stores, any specific reports or media issues, and provided a consumption-related profile of the community using program data in advance of the site visits.

- Key informant interviews. These were conducted with community leaders, including council members and administrators responsible for health and food security, health practitioners, teachers, day care operators, managers of other local institutions, and retailers and other buyers participating in the program.

- Focus Groups. The focus groups were designed to obtain the views of local consumers and health representatives about the transition to NNC, accessibility of nutritious foods, food prices now as compared to under the Food Mail Program, comparisons of their options for obtaining goods, availability and cost of country foods, and other related issues they may wish to raise. Focus groups were conducted in Cape Dorset, Nunavut and Poplar River, Manitoba and varied in size from 3-23 participants.

- Retail Store Observation. A visit to each of the retail stores receiving the NNC subsidy in each community visited was undertaken. Retail store analysis was used to determine availability and accessibility to food. This was assessed using a questionnaire containing different indicators to assess the characteristics of the food stores visited and included, for example, the percentage of the store dedicated to non-food departments (e.g. pharmacy, clothing) versus fresh produce departments (dairy, produce, deli, and meat); food related services offered (e.g. fresh bakery, butcher); promotional information on Nutrition North Canada Program and availability of information of healthy food (pamphlet, posters), etc. This questionnaire was revised from an American community food security assessment tool.Footnote 7 Additionally, the affordability and the quality/condition of 10 items of food were also noted in each community. The 10 items are part of the subsidized food list under Nutrition North Canada and part of the Eating Well with Canada's Food Guide: First Nations, Inuit and Métis.Footnote 8

A technical report of the case studies, including a summary of the observation tool was completed that responded to each key evaluation question.

2.4 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

2.4.1 Strengths

Existing documentation

A considerable strength for the evaluation is that the program has well documented the transition from the Food Mail Program to Nutrition North Canada and its current operation. The evaluation was able to take advantage of available documentation and quantitative data collected by the program at AANDC.

Multiple lines of evidence

The evaluation relied on the use of multiple lines of evidence in order to address the issues and questions identified for the evaluation. This not only helped to increase the rigor and strength of the findings but helped to compensate for any limitations affecting a particular line of evidence; for example, where interviewees declined to participate.

Interviewees

Key informant interviews as well as interviews included in the case studies have contributed significantly to the evaluation's findings. The range and diversity of opinions and experience among the respondents added to the strength and breadth of the evaluation. Further, many of the interviewees were helpful in supplying the evaluation team with additional documents and literature.

2.4.2 Limitations

Selection of focus group participants in case studies

A limitation on the selection of focus group participants in the case studies was that the recruitment of those participants was largely based on the assistance of a contact in the local community. Measures to mitigate any bias surrounding this practice included ensuring for a mix of individuals knowledgeable about the program but who also represented a cross-section of people from the community. Also, emphasis was placed on having the perspective of day-to-day consumers and not necessarily people employed by key stakeholders. Focus groups were conducted in all but Iqaluit, and involved community leaders, local residents, and health care practitioners.

Key Informant Interviews

Despite the large number of respondents identified as key informants (n=62), it was difficult to reach people for an interview. Over a quarter of key informants felt uncomfortable participating in the evaluation either because they did not feel familiar enough with the program or because they found the program contentious. As a result, the overall number of interviews completed (n=34) proved to be less than expected. Some key informant groups were more responsive as a group than others. For example, no member of the Oversight Committee was available to participate in an interview. There was also some difficulty reaching all the members of the Advisory Board. The protocol for reaching key informants was to attempt to reach them by phone and email multiple times.

AANDC-Specific Focus of the Evaluation

For the purposes of this evaluation, limited information was sought from Health Canada relating to Health Canada's culturally appropriate nutrition education activities, upon recommendation of the Working Group. The reason for this was largely due to the fact that, this being an implementation evaluation, the focus was mainly on AANDC's immediate outcomes and because an impact evaluation was being planned for fiscal year 2014-2015, which would be conducted jointly by AANDC and Health Canada.

However, because an intermediate outcome of NNC relates to the consumption of healthy foods, the evaluation needed to address all issues that may contribute to the achievement of this outcome. Therefore, while evaluation issues and questions around the education initiatives pertaining to Health Canada were not explicitly asked, the evaluation did address the issue of the extent to which residents in eligible communities have knowledge about healthy eating and skills to choose and prepare nutritious foods in the context of how it contributes to AANDC's intermediate outcome: consumption of healthy foods.

2.5 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) was the project authority for this evaluation and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process. The majority of the evaluation work was completed in house, with the assistance of Rick Gill of Alderson-Gill & Associates for a portion of the case studies. The EPMRB evaluation team identified key documents, provided a list of the communities selected for case studies, and names and contact information of First Nations and Inuit representatives as required. The team further expeditiously reviewed, commented on and approved the products delivered by the contractor.

An evaluation working group was formed in order to provide advice, as needed, to the evaluation team.

EPMRB evaluators who were not directly involved in the evaluation project conducted internal peer reviews for the methodology report and draft final report. The reviewers' work was guided by EPMRB's Peer Review Guide. This guide includes questions that reflect Treasury Board standards for evaluation quality and guidelines for final reports.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

The following sections examine issues related to relevance, including:

- continued need for the program;

- extent to which program objectives are aligned with government-wide priorities and link to AANDC's strategic outcomes;

- extent to which objectives of the program are consistent with the role and responsibilities of the federal government; and

- duplication or overlap with other programs, policies or initiatives.

Evidence is based on a triangulation of evidence from a literature review, key informant interviews, document review and case studies.

3.1 Continued Need

All lines of evidence indicate that there is a strong and definite need for the program. High levels of food insecurity have been reported in the North compared with other regions, indicating a need to support food procurement.

According to key informant interviews, case studies, and the literature review, Aboriginal people experience the highest rate of food insecurity in Canada compared to non-Aboriginal households.Footnote 9 The Inuit Health Survey (2007-2008) reported very high rates of food insecurity in Nunavut (68.8 percent), and high rates of food insecurity in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (43.4 percent) and the Nunatsiavut Region (45.7 percent). The literature review and case studies indicated that children in northern Canada have particularly high levels of food insecurityFootnote 10, which may have negative effects on health outcomes.Footnote 11 According to the World Health Organization "nutrition is an input to and foundation for health and development…better nutrition means stronger immune systems, less illness and better health. Healthy children learn better."Footnote 12

According to case studies and the literature review, food insecurity is associated with high costs of food and high cost of living in the North. Income is determined to be the strongest indicator of enabling access to healthy food, particularly for Aboriginal people.Footnote 13 Case studies and the literature review found high cost of living and lower incomes of Northerners contribute to difficulties accessing healthy food.Footnote 14 While median incomes are significantly lower for Inuit,Footnote 15 the cost of a healthy food basket is at least two times higher than a comparable basket in southern Canada.Footnote 16 Case studies and the literature review found that affording food in the North is even more difficult because of unemployment, low income, or those that are on social assistance.Footnote 17

The perception of key informant interviews confirmed that finding. The majority of respondents indicated a need for the program because of high food costs and cost of living in northern Canada. Some respondents cited a need for the program because of high costs in relation to low income and poverty in the north. Others considered a food subsidy program to be an essential program to living in the North, without which northern communities would be unsustainable.

Some literature sources noted the limited availability of healthy foods.Footnote 18 Case studies and the literature review found store bought foods are generally more expensive and less nutritious when compared to country-food options.Footnote 19 They also found that healthy foods are less available in the North because of remote geographic locations, resulting in lower food and nutrition outcomes for those areas. A few key informants stated a need for the program because of the difficult supply chain, high costs of shipping, and poor infrastructure. Some literature review sources and case studies found nutritious perishable foods are vulnerable to spoilage and damage while shipped long distances, but highly processed/packaged foods are easily transported and more readily available in stores.Footnote 20

Case studies and the literature review also found that poor health outcomes for northern Aboriginal people related to nutrition demonstrates a need for the program. Aboriginal people, particularly the Inuit, are generally worse off than other Canadians for every health measure.Footnote 21 Health problems in Aboriginal peoples related to diet include anemia, dental caries, obesity, heart disease and diabetes.Footnote 22 In the North, poor health outcomes are generally linked to widespread dietary inadequacies.Footnote 23

Poor health outcomes can generally be linked to the fact that case studies and the literature review found that residents generally rely on easy to prepare foods as an alternative to healthy country food options.Footnote 24 These foods are often frozen or pre-prepared and contain high fat and sugar and are low in nutritional content. The literature review confirms this finding.Footnote 25 Case studies and literature review found that a contributing factor to poor health outcomes included a lack of basic nutrition and health knowledge, as well as food preference. Footnote 26

Case studies and the literature review both report the importance of country food to Northerners and a declining consumption of country food in the North.

3.2 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

As per the 2012-2013 AANDC Program Alignment Architecture, Nutrition North is identified as a sub-activity of the program activity area Northern Governance and People. This corresponding program activity area contributes to the Department's strategic outcome area of the North through its expected outcomes of self reliance, prosperity and well-being for the people and communities of the North.

According to Canada's Northern Strategy, the North was identified as a "cornerstone" of the Government's agenda.Footnote 27 Through Canada's Northern Strategy, commitments were made toward several priority areas including exercising Arctic sovereignty, protecting environmental heritage, improving and evolving northern governance and promoting social and economic development. The launch of Nutrition North Canada was included as part of initiatives promoting social and economic development.

NNC contributes to that program and strategic outcome by improving access to nutritious perishable foods in isolated northern communities.

According to the 2012-2013 Report on Plans and Priorities for AANDC, NNC contributed to that expected result by:

- supporting northern communities and retailers to carry out the transition to Nutrition North Canada; and

- working closely with the program's Advisory Board, which represents the perspectives and interests of northern residents and communities and provides advice to the Minister on the management of the program.Footnote 28

3.3 Alignment with Government Roles and Priorities

According to key informant interviews, some respondents were of the view that the federal role to subsidize food in the North was required from a health perspective in that it contributes to improving the quality of foods available and supporting healthy outcomes in the North. A few respondents indicated that the objectives of the program fall within the inherent responsibilities of the federal government, suggesting there would be gaps if the federal government did not fulfill this responsibility.

Literature review and key informant interviews noted that, Canada has signed several international and domestic agreements related to a right to food:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) describes human rights to be protected internally, including Article 25(1), right to an adequate standard of living, including food.

- In 1976, Canada ratified and put into force the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), which was an internationally binding. It contains Article 11, which states a right to an adequate standard of living, including food, and the fundamental right to be free from hunger.

- In 1991, Canada ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which includes articles 24 and 27, which set out obligations for rights of children to health and to give adequate standard of living.

- A series of non-binding declarations were signed throughout the 1990's, including the World Declaration on Nutrition (1992), which recognizes food as part of a right to an adequate standard of living; the Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action (1996), which seeks clarification of content of the right to food, and Code of Conduct on the Human Right to Adequate Food (1997), which sets guidelines and principles for nations to implement right to adequate food, including state obligations at the national and international level.

- The Government responded to these agreements in 1998 with Canada's Action Plan for Food Security, which created a federal policy framework in response to commitments of World Summit Plan of Action and led to the formation of the Food Security Bureau within Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

- On November 12, 2010, the Government of Canada formally endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in a manner fully consistent with Canada's Constitution and laws. The Declaration speaks to the individual and collective rights of Indigenous peoples, taking into account their specific cultural, social and economic circumstances.

However, despite the above agreements related to a right to food, literature review also found that outside the Canadian Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms,Footnote 29 there is no statutory obligation that guarantees the right to food. Footnote 30

Further, literature review and key informant interviews indicate that responsibilities for various components of a food policy framework are fragmented across multiple federal, provincial and local jurisdictions, meaning that Canada does not have an overarching food policy.Footnote 31

At the same time, the Government of Canada invests in community-based programs such as the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program, Brighter Futures / Building Healthy Communities, Aboriginal Head Start on Reserve and Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative to promote nutrition and improved access to healthy foods. Local communities also operate programs that may contribute to similar long term outcomes (e.g. community freezers, food banks, nutrition education sessions, etc).

While there are some regional examples of food subsidy-related programs that aim to lower the price of certain healthy foods and which may contribute to similar long-term outcomes as NNC, the scope of these programs are not as broad as NNC, suggesting that they are complementary rather than duplicative.

Some programs identified by the literature review and through key informant interviews included the following:

- Air Foodlift Subsidy Program. Since 1997, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador has provided air freight subsidies on select food items to retailers as part of the Air Foodlift Subsidy Program. The subsidy is applied to products after the NNC subsidy. Many respondents referred to the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy Program as an example of complementary programming to NNC. No respondents were under the impression that the program was duplicative. Changes were made to the program in 2011 to coincide with the launch of NNC. These changes included making the subsidy a year-round subsidy, revising the eligible food list, increasing the air freight subsidy on fresh milk to 100 percent, and requiring retailers/wholesalers to be registered with NNC in order to be eligible for the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy Program. The total amount of rebate offered was reduced from $80,000 to $30,000 in 2011 with changes made as a result of NNC.

- The Kativik Regional Government in Northern Quebec, since 2002, has operated a Food Program, which reduces the cost on common items by 20 percent at eligible stores. Examples of eligible items include baking powder, flour, pastas, rice, diapers, washing detergent and toilet paper. In 2009, approximately $1.13 million in subsidy was applied.

- Northern Healthy Foods Initiative is a grants-based program of the Government of Manitoba that supports self-sufficient food security initiatives in communities such as revolving loan freezer purchases, gardens and greenhouses, community food planning, etc.

- Harvester Support Programs are supported by the Government of Nunavut, the Government of Northwest Territories, and the Kativik Regional Government. These programs help with the purchasing of equipment required to support fishing and hunting trips such as boats, snowmobiles, and camping equipment. For some programs, individuals are paid for their time hunting. Other programs support traditional youth hunting through elders. Food is often collected and shared with community members in need, particularly elders.

4. Evaluation Findings - Design and Delivery

The following sections examine issues related to design and delivery, including:

- the extent to which the program's design allows it to achieve results and the extent to which NNC has been implemented as planned;

- the clarity of AANDC and Health Canada roles and responsibilities;

- issues around governance structures and the extent to which oversight committees and external advisory board have been effective; and

- adequacy of data collection and reporting procedures for performance measurement.

These sections are based on the analysis and triangulation of evidence arising mostly from the document review, key informant interviews, case studies, and a review of available program data.

4.1 Program design

4.1.1 Supply-chain model

Evidence suggests that the NNC Program supply-chain model is well-suited to achieving program objectives of making food more accessible, largely in part because it enables retailers to organize their own shipping routes and secure competitive freight rates. Evidence from interviews and documents reviewed indicate that the supply chain design allows retailers the flexibility to make more economic choices and that the supply chain structure could result in the establishment of more efficient delivery routes.Footnote 32

Further, documents reviewed suggested the devolution of transportation responsibilities to retailers is meant to contribute to both cost-savings and capacity development.Footnote 33 Program documents outline the potential benefits, such as carrier systems under NNC having the capacity to lower the transportation costs per net kilo.Footnote 34 Thus, community stores are better able to influence airline schedules, allowing them to better marry trucking schedules, where they are available. A few key informants have acknowledged this fact as a factor to facilitate the achievement of results.

4.1.2. Program Eligibility Criteria

Program documentation indicates that in 2011-2012, under NNC, 82 communities were eligible for a full subsidy and 21 for a partial subsidyFootnote 35 and in 2012-13, 84 communities were eligible for a full subsidy and 19 for a partial subsidy.

To be initially eligible for Nutrition North Canada, a community must:Footnote 36

- Lack year-round surface transportation (i.e. no permanent road, rail) and marine transportation link to southern centres; and

- Have used Food Mail, the Department's previous northern transportation subsidy program. Communities that did not use the previous Food Mail Program are deemed ineligible for the subsidy under NNC.

Communities eligible for a full subsidy used the Food Mail Program extensively, which was defined as communities that received over 15,000 kg (annualized) of perishable food shipments or more than $4 per month per resident in transportation subsidies, between April 1, 2009, and March 31, 2010. Communities deemed eligible for a partial subsidy were those that made very little use of the Food Mail Program with between 100 and 14,999 kg (annualized) of perishable food shipments and less than $4 per month per resident in transportation subsidies during the same time period.

About half of the respondents interviewed indicated that the community eligibility criteria are an issue. Some key informants have questioned the terms of eligibility, explaining that there are many remote, fly-in communities that would greatly benefit from a food subsidy program, but are ineligible as a result of not utilizing the former Food Mail Program. Further, some communities have limited access to affordable healthy foods and would benefit from the subsidy, but do not meet the fly-in community criteria, despite being difficult to access by road. Although a few key informants recognized that including more communities would limit the amount of funding available given the funding cap of $53.9 million that is currently in place, they explained that there was an under-addressed need in some communities.

According to the document review, AANDC was expected to re-assess community eligibility in 2012-2013Footnote 37 to see whether any of the 19 communities currently on a partial subsidy should be on the full subsidy. AANDC will also consider whether any of the 30 fly-in communities currently not eligible should be eligible. According to interviews, a community eligibility assessment has not been completed at this time.

4.1.3 Food Eligibility List

From October 3, 2010, until the end of the Food Mail Program on March 31, 2011, non-food items, most non-perishable foods and some perishable foods of little nutritional value were deemed not eligible for subsidized airlift to eligible communities with access to seasonal marine transportation.Footnote 38

This change was announced on May 21, 2010, in conjunction with the Government announcing its plan to replace Food Mail with NNC. However, from the launch of NNC on April 1, 2011, to September 30, 2012, the list of items eligibleFootnote 39 for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy was expanded to include all food, as well as most non-food items that were eligible under the Food Mail Program.

The decision to adopt an expanded list of eligible products for this 18-month period was taken to help ensure a smooth transition to Nutrition North Canada and to allow for two more sealift and one more winter road cycles.

On October 1, 2012, the program implemented a list of foods eligible for subsidy focused on perishable, nutritious choices. This list was expected to be reviewed annually and changes made if necessary. It was expected that feedback from Northerners on these lists would be provided. The program expected this feedback to come through the Advisory Board and through a survey that the program was to have conducted.

Some of the interview respondents indicated that they were dissatisfied with the change in eligible food items under NNC to exclude non-food items and some dry non-perishable food items. It was pointed out that many community members relied on non-food items such as snow mobile parts and diapers, which have become more expensive without the subsidy. It was additionally noted that high arctic communities receive infrequent shipments of Level-1 foods, and are often left with canned items that are no longer subsidized since they are mainly shipped via sealift or winter roads.

4.1.4 Country Foods

Documents reviewed indicate that the harvesting of country foods can have significant costs, and only those with sufficient income can afford to do it.Footnote 40The case studies additionally indicate that access to country foods is also limited by not only high cost, but additionally a lack of distribution and food handling capacity, and declining local food sources.