Summative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan

Final Report

Date : April 2013

Project No. 12029

PDF Version (324 Kb, 41 Pages)

Table of contents

Executive Summary

Purpose of the evaluation

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook a summative evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan. The primary purpose of the evaluation is to obtain an independent and neutral perspective on how well the Action Plan is achieving its expected outcomes. Evaluation results were based on the analysis and triangulation of data obtained through document and data review, file review and key informant interviews. The Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved at the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in April of 2012. Fieldwork was conducted between October and December 2012.

Objective and intended results of the Action Plan

The overall objective of the Action Plan is to ensure that specific claims are resolved with finality in a faster, fairer and more transparent way.

The key results that AANDC set-out to achieve in the first three-to five-years are:

- The establishment and operation of the Specific Claims Tribunal, including the Registry to support the work of the Tribunal;

- Establishment and operation of mediation services for First Nations who are negotiating their specific claim with Canada;

- Complete review and assessment of all existing and new specific claims by the end of the fiscal year 2010-2011;

- Increase in the number of negotiation tables from 100 to 120 annually; and

- Increase the number of specific claims that are successfully resolved through negotiations or through a hearing conducted by the Specific Claims Tribunal.

These results are expected to contribute to the achievement of the following long-term outcomes:

- Justice for First Nation claimants;

- Certainty for government, industry and Canadians respecting disputed lands, resources or relationships; and

- Sustainable use of lands and resources.

Evaluation Findings

AANDC has put in place practices and procedures to cover all aspects of the claim process. The Department has created clear and efficient processes to facilitate the participation of other parties, whose actions are beyond the control of AANDC and the Department of Justice, but that can impact the ability to meet the three-year timeframe for negotiations.

Achievements include:

- The Specific Claims Tribunal has been established, including the Registry, which supports the work of the Tribunal.

- The backlog of claims in assessment at the time the Specific Claims Tribunal Act came into effect has been cleared.

- The total number of claims in negotiation has increased significantly under the Action Plan.

- The preconditions for justice and certainty are in place within the specific claims process and the claims that have been settled through negotiations are largely achieving these outcomes.

- Over time, negotiated settlements, decisions from the Tribunal and the body of law that will emerge from the Tribunal are expected to contribute to a greater level of justice and certainty.

- Specific Claim settlements are contributing to the sustainable use of lands and resources, most notably through the additions to reserve process.

Areas for improvements:

- The number of claims resolved (settled) through negotiations has not yet increased under the Action Plan. However, a number of the backlog claims are currently in the negotiation phase, which may contribute to this outcome in the near future.

- Though mediation services are available, access has been minimal under the current operational model and therefore, the fourth pillar of the Action Plan, better access to mediation, is not being achieved.

Risks identified:

- Significant numbers of specific claims have been concluded without finality and could proceed to the Tribunal, or be submitted as a new claim to the specific claims process.

- Potential risk that the Tribunal decisions on validity could impact the legal assessment of unresolved claims should they be resubmitted to the Specific Claims Branch.

- It is anticipated that more pressure may be placed on the Additions to Reserves process as the backlog claims currently in the negotiation phase are concluded.

- Current level of funding for settlement may be insufficient to address the expected volume of compensation that will be needed.

- Aboriginal organizations are not acknowledging improvements made to the specific claims process, which may affect confidence in the integrity and effectiveness of the new process to resolve specific claims.

Evaluation Recommendations

- As part of the risk assessment framework that is to be undertaken by Treaties and Aboriginal Government Senior Assistance Deputy Minister (recommendation 2 of the Internal Audit Report of November 2012), include a risk strategy to manage the large number of claims that are considered "concluded" by AANDC but which have the potential to be submitted to the Tribunal or submitted as a new claim to the specific claims process. This risk strategy should be updated as decisions of the Tribunal are rendered.

- Through discussions with First Nation leaders, develop and implement a strategy to allow for greater use of mediation services.

- Put in place mechanisms that support the relationship between the Action Plan and the Additions to Reserves process.

- Address current funding for settlement of specific claims as it may be insufficient to address the expected volume of compensation that will be required.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Summative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan

Project #: 12029

1. Management Response

The Specific Claims Action Plan was announced by the Prime Minister in June 2007. As confirmed by the Formative Evaluation, which was completed in April 2011, and by the Summative Evaluation, much progress has been made with the implementation of the Action Plan. The Summative Evaluation report also makes findings that were not anticipated by the Specific Claims Branch, specifically in respect to mediation services, and the Addition to Reserve Policy. The Specific Claims Branch will examine those findings more closely, and will address them taking into account the intention of the Action Plan, the confines of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, and the government's commitment to the quick and fair resolution of specific claims.

The findings of the Summative Evaluation will be used to inform: the legislative review of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act required in 2013-14. The findings will also be taken into consideration in the context of work planning, reporting on progress made in resolving specific claims, briefing notes for senior officials, and briefing material prepared for Standing Committee appearances by AANDC officials.Response to Recommendation 1: A recent Audit of the Specific Claims process was completed in the fall 2012. As part of the Management Response Action Plan, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Treaties and Aboriginal Government (TAG) committed that a Specific Claims risk assessment framework will be undertaken and integrated into the corporate risk assessment framework. The Specific Claims risk assessment framework will address elements unique to the Specific Claims process, including the impact of the Specific Claims Tribunal. It is noted that it is entirely at the discretion of a First Nation to refer a claim to the Tribunal. In this regard, any estimate of the number of claims that might be referred to the Tribunal would be speculative. That being said, Specific Claims Branch will ensure that the volume of concluded claims with the potential to be submitted to the Tribunal, or the Specific Claims Branch, is considered in the risk assessment.

Response to Recommendation 2: The report does not distinguish between better access to mediation services, which was the Action Plan commitment, and use by negotiating parties of mediation services. Access to independent mediation services has been made easier with the creation of the Mediation Services Unit. AANDC does not administer the mediation process; the Mediation Services Unit facilitates access to independent mediation services by providing administrative support to negotiating parties to use standing offers.

The document also notes that the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) has called "for the establishment of an independent mediation centre that could support all stages of the specific claims process, not only at the negotiation stage." The government's commitment, through Justice at Last, was to facilitate access to independent mediation services to overcome impediments in negotiation processes. This commitment was met.

The report recommends that "Through discussion with First Nation leaders, develop and implement a strategy for greater use of mediation services. This will assist in achieving commitments made under the Action Plan and in addressing First Nations' concerns." TAG remains ready to meet with First Nation leaders to explain the access to the mediation process and to do the same with individual First Nations who are in negotiations. Sessions will be offered to TAG's negotiators to refresh their knowledge of the use of mediation and ensure that First Nations are made aware that such services exist.

In response to recommendation 3: The Additions to Reserves (ATR) Policy is currently being amended by the Lands and Economic Development Sector, in consultation with the AFN. Further, the Specific Claims Lands Implementation Committee has been established within AANDC with members from the Specific Claims Branch and the Lands and Economic Development Sector, with representatives of both Headquarters and regions. This new committee will be a forum to identify and address issues arising from ATR opportunities arising from specific claims.

In response to recommendation 4: A $2.5 billion settlement fund was established as part of the Justice at Last initiative. The Specific Claims Settlement Fund is to pay for negotiated specific claim settlement agreements and for awards made by the Specific Claims Tribunal up to a value of $150 million per claim. The Specific Claims Settlement Fund is monitored closely by AANDC, and, pursuant to the Access Protocol, the Department of Finance and Treasury Board. The fund is set at $250 million per year over ten years (fiscal year 2018-2019) to ensure sufficient funding is available to allow Canada to meet its obligations stemming from negotiated settlements and awards of the Specific Claims Tribunal.

2. Action Plan

(Actions, Manager, Planned Start and Completion Dates to be completed by Specific Claims Branch)

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. As part of the risk assessment framework that is to be undertaken by TAG Sr. ADM (recommendation 2 of the Internal Audit Report of November 2012), include a risk strategy to manage the large number of claims that are considered "concluded" by AANDC but which have the potential to be submitted to the Tribunal or submitted as a new claim to the specific claims process. This risk strategy should be updated as decisions of the Tribunal are rendered. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, TAG | Start Date: Completion: |

| Specific Claims Branch will ensure that concluded claims which have the potential to be referred to the Tribunal, or re-submitted to the Specific Claims Branch is included in the risk assessment. | September 30, 2013 | ||

| 2. Through discussions with First Nation leaders develop and implement a strategy to allow for greater use of mediation services. | We ___partially__ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Director General, Negotiation Central | Start Date: Completion: December 2013 |

| TAG is of the view that access to mediation has been achieved; however, parties are not making use of the better access to mediation.

TAG remains ready to meet with First Nation leaders to explain the access to mediation process and to do the same with individual First Nations who either are in negotiations or about to commence negotiations. Training sessions will continue to be provided to TAG's negotiators with training in how to effectively use mediation. |

|||

| 3. Put in place mechanisms that support the relationship between the Action Plan and the Additions to Reserves process. | We _do__ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Director General, Specific Claims Director General, Lands & Environmental Management |

Start Date: Completion Done |

| The ATR Policy is being amended, with the participation of the AFN. Further the Specific Claims Lands Implementation Committee has been established with members from the Specific Claims Branch and the Lands and Economic Development Sector, both Headquarters and in regions, to be a forum on to identify and address issues arising from ATR opportunities arising from specific claims. | |||

| 4. Address current funding for settlement of specific claims as it may be insufficient to address the expected volume of compensation that will be required. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Director General, Specific Claims | Start Date: Completion |

| The Specific Claims Settlement Fund continues to be monitored closely by AANDC and, pursuant to the Access Protocol, the Department of Finance and Treasury Board to ensure sufficient funding is available to allow Canada to meet its obligations stemming from negotiated settlements and awards of the Specific Claims Tribunal. | 2013-14 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on February 15, 2013, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on February 15, 2013, by:

Jean-Francois Tremblay

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Treaties and Aboriginal Government

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Summative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on April 25, 2013.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook a summative evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan (hereafter the Action Plan). The primary purpose of the evaluation is to obtain an independent and neutral perspective on how well the Action Plan is achieving its expected outcomes as well as to identify any unexpected impacts resulting from the Action Plan.

This report is divided into five sections. Section 1 provides an overview of the Action Plan; Section 2 describes the methodology associated with the evaluation; Sections 3 and 4 detail the evaluation findings that have emerged during the data collection process; and Section 5 provides conclusions and recommendations.

1.2 The Specific Claims Action Plan

1.2.1 Background and Scope/Activities

Specific claims, generally, are claims made by a First Nation against the federal government, which relate to the administration of land and other First Nation assets and to the fulfillment of Indian treaties. The nature of grievances qualifying as specific claims can vary widely, reflecting the diverse historical relationships between different First Nations and the Government of Canada. Examples include the failure to provide enough reserve land, the improper management of First Nation funds and the unlawful surrender of reserve lands. Settling specific claims in a way that satisfies both the Government and the First Nations is an important priority, not only because doing so provides First Nations with the means and resources to promote social and economic development, but also because it helps to build trust between the two parties by rectifying historical injustices.

Canada's Specific Claims Policy was established in 1973 to assist First Nations in addressing their claims through negotiations with the Government as an alternative to litigation. The policy was clarified in 1982 with the publication of Outstanding Business: A Native Claims Policy, Specific Claims wherein Canada commits to uphold its responsibilities to Indian Act bands when treaty or other legal obligations have not been honoured. The primary objective of the federal government with respect to the Specific Claims Policy is to discharge its lawful obligation, as determined by the courts if necessary. Negotiation, however, remains the preferred means of settlement by the federal government. The Specific Claims Policy establishes the principles and process for resolving specific claims through negotiation.

This process was criticized by First Nations and other parties (notably the 2006 Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples "Negotiation or Confrontation: It's Canada's Choice"). Criticisms focused on a failure to process and review claims in a timely manner, and a perceived conflict of interest arising from continuing federal government control over the process, as well as a lack of an independent body to make the process more fair and effective. Canada's response to the Senate Committee Report, announced on June 12, 2007, was Justice At Last: Specific Claims Action Plan.

The Specific Claims Action Plan

Justice At Last: Specific Claims Action Plan set in motion a fundamental reform of the specific claims process, which was intended to bring increased fairness and transparency to the process. The Action Plan is based on four pillars:

- Impartiality and fairness: An Independent Claims Tribunal;

- Greater transparency: Dedicated Funding for Settlement;

- Faster processing: Improving internal government procedures; and

- Better access to mediation: Refocusing the work of the current Indian Specific Claims Commission

The new specific claims process includes four stages: Claim Submission and Early Review; Research and Assessment; Recommendation and Decision Making; and, Negotiation and Implementation.

Stage 1: Claim Submission and Early Review

The process begins when a First Nation submits a claim. The First Nation is responsible for ensuring that its submission is complete and accurate.

Within six months of having received the claim, the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development will inform the First Nation whether the submission meets the Minimum Standard. (The Minimum Standard was established by the Minister in accordance with the Specific Claims Tribunal Act and is set out in The Specific Claims Policy and Process Guide.) This early review of the claim submission is conducted jointly by the Specific Claims Branch and the Department of Justice Canada. If a claim does not meet the Minimum Standard, it is returned to the First Nation with an explanation of why it was not filed. If a claim does meet the Minimum Standard, the First Nation is informed that it has been filed with the Minister. The date of filing is the beginning of the three year "research and assessment" stage of the process.

Stage 2: Research and Assessment

Once a claim has been filed, the Minister has three years in which to render a decision whether to accept the claim for negotiation. During this stage, the historical record of the alleged breach(es) is reviewed by the Specific Claims Branch for completeness and accuracy, and a legal review of the allegations is undertaken by the Department of Justice. The Department of Justice provides advice to AANDC as to whether the claim gives rise to an outstanding lawful obligation on the part of the federal government.

Stage 3: Recommendation and Decision Making

The Claims Advisory CommitteeFootnote 1 reviews the results of the historical and legal review and makes a recommendation to the Minister as to whether the claim should be accepted for negotiation. The recommendation to the Minister includes the notification to the First Nation regarding the disposition of the claim.

The notification must be sent to the First Nation within three years of the claim having been filed. If a First Nation has not received notification of a decision in that time, it may refer its claim to the Tribunal. If a claim is not accepted for negotiation, the First Nation will be informed of the reasons for the decision and the First Nation may refer its claim to the Tribunal.

If a claim is accepted for negotiation, the First Nation will be informed of the decision, the basis upon which the claim will be negotiated, and will be asked to indicate whether it is willing to engage in negotiations on the basis of the terms set out in the letter of acceptance. The date on which the First Nation is advised of the Minister's decision to accept the claim for negotiation marks the beginning of the three year "negotiation and settlement" stage of the process.

Stage 4: Negotiation and Settlement

A First Nation will be asked to indicate whether it is willing to negotiate a settlement. If, after three years, a negotiated settlement has not been reached, the First Nation may refer its claim to the Tribunal.

Financial mandates for claims in negotiation are approved as follows: financial mandates of $7 million or more, to a maximum of $150 million, require the approval of Treasury Board; the Deputy Minister may approve financial mandates for settlements between $1 million and $7 million; the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Treaties and Aboriginal Government may approve mandates for settlements between $500,000 and $1 million; and the Director General, Specific Claims Branch may approve mandates up to a maximum value of $500,000. If a claim exceeds $150 million, Cabinet authority is necessary to i) accept the claim for negotiation; and ii) settle the claim (i.e. settlement mandate).

1.2.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

As per the Transfer Payment Program Terms and Conditions, the overall objective Canada's Action Plan is to ensure that specific claims are resolved with finality in a faster, fairer and more transparent way.Footnote 2

Achievement of this goal will be supported by:

- The establishment and operation of the Specific Claims Tribunal, an independent body with binding decision-making powers and the authority to establish monetary awards up to a maximum of $150 million per specific claim; and

- The implementation of a streamlined process to accelerate the reduction of the specific claims backlog.

The key results that AANDC set-out to achieve in the first three-to five-years are:

- The establishment and operation of the Specific Claims Tribunal, including the Registry to support the work of the Tribunal;

- Establishment and operation of mediation services for First Nations who are negotiating their specific claim with Canada;

- Complete review and assessment of all existing and new specific claims by the end of the fiscal year 2010-2011;

- Increase in the number of negotiation tables from 100 to 120 annually; and

- Increase the number of specific claims that are successfully resolved through negotiations or through a hearing conducted by the Specific Claims Tribunal.

These results are expected to contribute to the achievement of the following long-term outcomes:

- Justice for First Nation claimants;

- Certainty for government, industry and Canadians respecting disputed lands, resources or relationships; and

- Sustainable use of lands and resources.

1.2.3 Alignment with departmental priorities and link to the Program Alignment Architecture

The negotiation and implementation of specific claims remain one of AANDC's priorities. As stated in the 2011-2012 Departmental Report on Plans and Priorities, by negotiating and implementing comprehensive land claims, specific claims, special claims and self-government agreements, the federal government will address historic and modern claims, strengthen relationships between Aboriginal groups and all levels of government; support capable and accountable Aboriginal governments, and provide clarity over the use, management and ownership of lands and resources. Plans for meeting this priority include continuing to resolve specific claims.

Specific claims are situated under the Government Pillar / Co-operative Relationships / sub-activity 1.2.2 of AANDC's Program Alignment Architecture. The Specific Claims sub-activity expected result is that Canada fulfils its long standing obligations to First Nations arising out of treaties and the administration of lands, band funds and other assets. These results are being measured by:

- Percentage of claims under assessment addressed within legislated three years.

- Number of claims in negotiation addressed.Footnote 3

1.2.4 Management

AANDC - The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector has the overall responsibility for ensuring that the Specific Claims Action Plan is implemented effectively with appropriate use of human and financial resources. This accountability also extends to monitoring and assessment activities.

The Specific Claims Branch of AANDC is responsible for the operation, administration, and management of the Specific Claims Process and Policy as envisioned in the Specific Claims Action Plan. Specific responsibilities include:

- Receiving specific claim submissions from First Nations and assessing them against the Minimum Standard;

- Filing specific claims that meet the Minimum Standard with the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development;

- Making recommendations to the Minister as to whether a claim should be accepted for negotiation;

- Negotiating the settlement of specific claims with First Nations;

- Monitoring and assessing negotiating tables and reporting results annually;

- Formulating financial mandates to settle specific claims;

- Paying settlements negotiated by AANDC and monetary awards issued by the Specific Claims Tribunal;

- For claims that are before the Tribunal, carrying out a substantive role by ensuring policy objectives are respected and facts related to claims before the Tribunal are correct;

- Administering the Specific Claims Settlement Fund; and

- Collecting performance data and reporting results.

The Department of Justice provides advice to AANDC as to whether a claim gives rise to an outstanding lawful obligation on the part of Canada. It also provides legal advice to AANDC during the negotiation process and in Claims Advisory Committee meetings. If the claim proceeds to the Specific Claims Tribunal, Department of Justice will represent the interests of Government

The Specific Claims Tribunal is an independent adjudicative body with the authority to make binding decisions about the validity of a specific claim. It can award monetary compensation to a maximum value of $150 million per claim.

The Specific Claims Tribunal Registry is the administrative arm of the independent Specific Claims Tribunal and is designated as a government department under Schedule 1.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The Claims Advisory Committee is chaired by the Director General of the Specific Claims Branch and is comprised of senior AANDC and Department of Justice officials. The Committee issues recommendations to the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development on whether claims should be accepted for negotiation. The Committee also recommends financial mandates for approval.

The Mediation Services Unit arranges independent mediation services during negotiations at the joint request of First Nations and AANDC negotiators.

1.2.5 Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The following entities and organizations can benefit from the resolution of specific claimsFootnote 4:

- First Nations – greater certainty over lands and natural resources; cash/land settlements that can support community development; and, resolution of historical grievances;

- The Government of Canada – the interests of which are primarily, but not exclusively, managed by AANDC, the Department of Justice, the Department of Finance, and the Treasury Board Secretariat;

- Provincial and territorial governments – greater certainty over lands and natural resources;

- Aboriginal representative organizations – resolution of claims;

- Local governments adjoining First Nation communities – improved relationships and enhanced ability to make plans respecting land management, natural resources and provisions of services; and

- Private Sector – improved confidence in their business and investment decisions respecting First Nation interests in lands and natural resources.

1.2.6 Resources

Annual funding of $250 million over a ten-year period commencing in 2009-2010, totaling $2.5 billion, was allocated to the Specific Claims Settlement Fund for the purpose of paying specific claims settlements negotiated by AANDC or awards made by the Specific Claims Tribunal.

1.2.7 Audit and Evaluation Activities

In addition to this summative evaluation, a Formative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan was completed in April 2011. The purpose of the formative evaluation was to assess the extent to which the design and delivery of the Action Plan is supporting the achievement of the departmental objectives with respect to the resolution of specific claims, to identify opportunities to improve the Action Plan's design and implementation, and to assess how well the Action Plan is achieving its immediate results.

The formative evaluation concluded that the objectives of the Action Plan are strongly aligned with government priorities; the Action Plan is addressing long standing concerns of First Nations; the new timeframe has accelerated the processing of specific claims; significant financial resources have been assigned to the Action Plan and appear sufficient; and the Action Plan is an appropriate and efficient process to achieve expected results. The evaluation also found areas where improvements could be made, including addressing the lack of clarity related to the process for claims over $150 million; how activities under the mediation services pillar will be used and what processes will be followed to offer these services; and the level of feedback provided to First Nations whose claims have not met the Minimum Standard. The evaluation cited concerns that not enough time is being provided for negotiations, under the three year operational model, for large and complex claims. Specific Claims Branch has responded to all recommendations.

An Internal Audit of AANDC Support to the Specific Claims Process was recently completed. The audit assessed the adequacy and effectiveness of AANDC controls in relation to its obligations. Overall, the audit found governance and key operational processes in place to support the efficient and effective delivery of required services and support to the Specific Claims Process.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation scope and timing

This summative evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan covers activities that occurred between the fiscal years 2008–2009 and part of 2012–2013. As the focus of the evaluation is on the Action Plan — not the entire specific claims process — the Specific Claims Tribunal and the Specific Claims Tribunal Registry were not included in the scope of the evaluation. While the Specific Claims Tribunal was formed as a result of the Action Plan, it is an independent adjudicative body and the activities of it and its Registry are beyond the direct influence of the Action Plan. However, the evaluation assessed how the Tribunal's operations have impacted the work of Department of Justice Canada, AANDC and First Nations. The evaluation also excludes any assessment of legal opinions provided by the Department of Justice in support of the specific claims process.

Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved by AANDC's Evaluation Performance Measurement and Review Committee on April 23, 2012. Fieldwork was conducted between October and December 2012. EPMRB contracted the services of PRA Inc. to provide assistance during all stages of the evaluation process.

2.2 Evaluation issues and questions

The evaluation focussed on assessing the performance of the Action Plan, including the issue of effectiveness and the issue of efficiency and economy. An assessment of the relevance of the Action Plan is not included since it was covered in detail in the formative evaluation of the Action Plan completed in April 2011. Table 1 details the evaluation issues and questions covered by this evaluation.

Table 1: Evaluation Issues and Questions

Performance – Effectiveness

1. To what extent have the three to five-year planned results been achieved:

1a) The establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal, including Registry to support the work of the Tribunal.

1b) Improved access to independent mediation services during the negotiation of settlement agreements.

1c) Complete the research phase of the Research and Assessment and Recommendation and Decision-Making stages of the specific claims process for all "backlog" claims by October 16, 2011.

1d) An increase in the number of negotiation tables from 100 to 120 annually within the three-year legislated time frame.

1e) An increase in the number of specific claims that are resolved through negotiations or through a hearing conducted by the Specific Claims Tribunal.

1f) Implementation of practices/procedures that will sustain timely resolution of claims.

2. To what extent are the longer-term results being achieved?

2a) Justice for First Nations claimants.

2b) Certainty for government, industry, and Canadians respecting disputed lands, resource, or relationships.

2c) Sustainable use of lands and resources.

3. What are the connections between the activities being undertaken through the Specific Claims Action Plan and the intended results?

3a) What are the necessary preconditions for the intended results to occur?

4. What has been the impact of achieving/not achieving the intended results on AANDC, Department of Justice and First Nations?

5. Are there any unintended results (either negative or positive) taking places as a result of the Specific Claims Action Plan?

Performance: Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

6. Is the most appropriate and efficient process in place to achieve results and meet government's commitments to resolve specific claims?

7. Have operational and policy issues arisen because of the character of the Specific Claims Tribunal?

8. Has the Action Plan made the specific claims process more responsive to First Nations and Canadians?

9. Is the allocated funding for settlement sufficient?

10. Are there policy or process obstacles that impede the settlement of claims within the three-year operational time lines?

11. Are sufficient resources in place to sustain successes achieved and prevent recurrence of conditions that resulted in the process deficiencies identified by the Senate Standing Committee?

2.3 Evaluation methods

The results of the evaluation are supported by findings that were collected using a number of research methods.

2.3.1 Document and data review

The document and data review constituted a significant source of information for this evaluation. It included a thorough review of background documents, publications related to the Action Plan, and performance measurement materials.

2.3.2 File review

A total of 29 specific claims files were reviewed as part of this process. The selection of files for this review was the same as the one used for the Internal Audit of AANDC Support for the Specific Claims Process, which was completed in 2012. The selection of files took into account the regional distribution of files and their status (under assessment, concluded, and settled). The review was done on-site in both the Headquarters and British Columbia regional offices of AANDC.

2.3.3 Key informant interviews

A total of 32 interviews (including four group interviews) were conducted with key informants from the following groups:

- AANDC management, research and assessment, and negotiators (n=16)

- The Department of Justice (n=2)

- The Specific Claims Tribunal (n=2)

- Provincial government departments involved with processing or negotiating specific claims (n=4)

- First Nations communities and organizations (n=8)

2.4 Quality Assurance

The evaluation was directed and managed by EPMRB in line with the EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process. Quality assurance has been provided through the activities of the working group and an advisory group comprising representatives from the Specific Claims Branch and the Department of Justice. Preliminary findings were presented to the working and advisory groups in December 2012.

2.5 Limitations

Due to the nature of specific claims, files often contain confidential and protected information. One challenge was to incorporate this information without compromising the confidentiality of claims. As a result, the evaluation is written in general terms without explicit reference to individual claims. Furthermore, legal opinions prepared by Department of Justice Canada were not reviewed as they are protected by solicitor-client privilege.

Because the Action Plan was launched only five years ago, long-term results cannot be fully assessed at this time. However, the evaluation was able to provide an assessment on the achievement of long-term results to date.

3. Evaluation Findings: Effectiveness

The evaluation looked for evidence that the expected medium- and long-term results of the Action Plan have been achieved.

3.1 Achievement of medium-term results

AANDC set out to achieve medium-term results in the first three to five years of operationsFootnote 5. Table 2 provides a summary of the degree to which these expected results were achieved.

| Medium Term Results | Achievement of Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal, including the Registry to support the work of the Tribunal. | The Specific Claims Tribunal and Registry have been established. | Achieved |

| 2 | Establishment and operation of mediation services for First Nations who are negotiating their specific claim with Canada. | A mediation support unit and a roster of mediators have been established, access has been minimal under the current operational model and therefore, the fourth pillar of the Action Plan, better access to mediation, is not being achieved. | Not Achieved |

| 3 | Complete review and assessment of all existing and new specific claims by the end of the fiscal year 2010-2011. | The backlog of claims in assessment at the time the Specific Claims Tribunal Act came into effect has been cleared. | Achieved |

| 4 | Increase in the number of negotiation tables from 100 to 120 annually. | The total number of claims in negotiation has increased significantly under the Action Plan. | Achieved |

| 5 | Increase thenumber of specific claims that are resolved through negotiations or through a hearing conducted by the Specific Claims Tribunal. | The number of claims resolved (settled) through negotiations has not yet increased under the Action Plan. However, a number of the backlog claims are currently in the negotiation phase, which may contribute to this outcome in the near future. | To be determined |

The following provides details of the evaluation findings related to each of the medium-term results.

3.1.1 Establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal

The Specific Claims Tribunal is operational, and is supported by a fully-functioning Registry, which operates as a distinct entity under the Financial Administration Act. The Tribunal is composed of five appointed members and is currently dealing with 33 claims. It has rendered one decision on the validity of a claim.

Rules of practice and procedure

Rules of practice and procedure were formally adopted in June 2011, paving the way for the Tribunal to hear its first case. A central component of the current set of rules of practice and procedure is the proposed structure to address claims that have been submitted. Typically, and pending the approval of both parties, the Tribunal proceeds in two distinct phases. First, it holds hearings on the validity of a claim, and, should the validity of the claim be confirmed, it then proceeds with a hearing regarding the appropriate compensation.

Decision rendered to date

At the time of the evaluation, the Tribunal had rendered one decision regarding the validity of a claim. The claim involved the Osoyoos Indian Band in British Columbia and dealt with the fiduciary duty of the Crown to protect the interest of the band in relation to reserve land allocated to a railway company for railway purposes.Footnote 6 The band submitted a specific claim to AANDC in August 2005, and was informed in February 2011 of the Government of Canada's position that the claim did not disclose any outstanding lawful obligation on its part. The Osoyoos Indian Band filed a declaration of claim with the Tribunal in July 2011, and the Tribunal rendered its decision on validity in July 2012. The Tribunal concluded that Canada did breach "its fiduciary duty to the Osoyoos Band when it failed to take action to restore the interest of the Band in the Right of Way land."Footnote 7 At the time of this report, hearings on compensation had yet to proceed.

3.1.2 Establishment and operations of mediation services

The establishment of the mediation unit and the roster of mediators

Following the release of the Action Plan, AANDC established a mediation support unit and a roster of mediators. In the months of August and September 2011, AANDC's mediation unit issued two Requests for Proposals, including one set aside for Aboriginal suppliers in accordance with the federal government's Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Business. The selected mediators were issued a standing offer, allowing negotiating First Nations and Canada to use their services on a voluntary basis as they see fit, to support the negotiating process. In order to access the services, all parties to the negotiation need to agree to seek assistance from a mediator. In addition to posting information on the Department's website, the mediation unit sent a letter in August 2011 to all First Nations involved in negotiation to inform them of the availability of these services.

Improved access to mediation services

One of the four pillars of the Action Plan is better access to mediation.Footnote 8

Every reasonable effort will be made to achieve negotiated settlements and cases would only go to the tribunal when all other avenues have been exhausted. Before that happens, Canada and First Nations must have somewhere to turn when negotiations sour. Mediation is an excellent tool that can help parties in a dispute to reach mutually beneficial agreements. Canada recognizes that this tool should be used more often in stalled negotiation and is committed to increasing its use in the future.Footnote 9 (emphasis added)

The evaluation concludes that though mediation services are available, they are not being accessed to any extent under the current operational model and therefore, the fourth pillar of the Action Plan, better access to mediation, is not being achieved. The evaluation found only one instance of the mediation services having been accessed.

Evaluation findings indicate that the current process used to address specific claim leaves few opportunities for mediation activities to occur. Once a claim has been filed with the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development and the research and assessment process is undertaken, there is no direct interaction and dialogue occurring between the First Nations claimant and the Specific Claims Branch. Only when an offer to negotiate has been issued and accepted, will there be direct interaction between the two parties. At this point the parties will discuss some of the principles and information sources that will be used to value the claim. Mediation services could be used during these discussions. The negotiator then works with the Valuation and Mandating Unit of the Specific Claims Branch to determine the actual compensation amount. This amount is not discussed with the First Nation until an offer is tabled, at which point Canada does not expect to engage in any further negotiation because the offer is considered to be the best offer that Canada can make in accordance with its understanding of the applicable compensation criteria. If the First Nation disagrees with the offer it can submit new evidence for consideration, which could lead to a new offer being tabled by Canada.

First Nation opposition to the current mediation model

First Nation organizations continue to express opposition to the current mediation model. In March 2010, the British Columbia Union of Indian Chiefs passed a resolution denouncing the model retained by AANDC, adding that it did not "recognize the fairness, independence, impartiality, openness and transparency of a mediation process that is housed and administrated by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada and that is limited to only one stage in the process for resolving specific claims."Footnote 10 The motion also encouraged British Columbia First Nations to reject and oppose any mediation services that do not reflect the principles as articulated by the Justice at Last Initiative and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Assembly of First Nations also echoed these same concerns and has repeatedly called for the establishment of an independent mediation centre that could support all stages of the specific claims process, not only at the negotiation stage.Footnote 11

3.1.3 Completing research phase for all backlog claims

The Specific Claims Branch has eliminated the backlog of claims that were in the research and assessment stage at the time that the Specific Claims Tribunal Act came into effect in October 2008. Under the new model introduced with the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, a First Nations claimant can turn to the Tribunal if the Specific Claims Branch has not completed the research and assessment stage three years after a claim has been filed with the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (met the minimum standard). In October 2008, a total of 541 files were in research and assessment. Three years later, in October 2011, all these files had been assessed and all of the associated First Nation claimants had been informed about the outcome of that assessment.

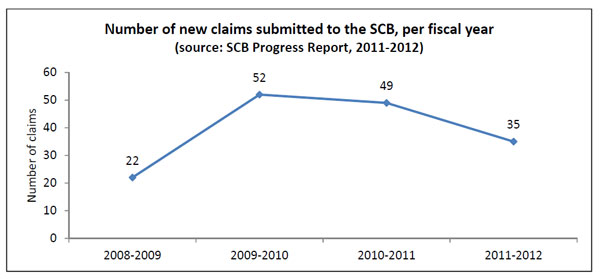

With the backlog cleared, the Specific Claims Branch does not anticipate difficulties in completing the research and assessment process for new claims submitted by First Nations. As illustrated in Figure 1, the number of new claims submitted to the Specific Claims Branch per year has varied between 22 and 52 during the four years that followed the launch of the Action Plan. As of November 2012, 99 files were under research and assessment.Footnote 12

Figure 1

Text description of Figure 1

This figure reflects the number of new claims submitted to the SCB for each fiscal year between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012. The number of claims is indicated on the "Y" axis, and the respective fiscal years is indicated in the "X" axis. In 2008-2009 there were 22 new claims submitted to the SCB. In 2009-2010, the number of new claims submitted to the SCB peaked sharply to 52, nearly doubling the number submitted the previous year. The following two fiscal years showed a slow decrease in the number of new claims, first to 49 in 2010-2011 and a further decrease to 35 in 2011-2012.

3.1.4 Increase in the number of claims in negotiation

The total number of claims in negotiation has increased significantly under the Action Plan. As illustrated in Figure 2, there were 126 claims in negotiation as of March 31, 2008. Four years later, that number had more than doubled to 280. The most significant increase occurred during the fiscal year 2011–2012.Footnote 13 The increased number of claims in negotiations is directly linked to the success in clearing up the backlog in assessment.

Figure 2

Text description of Figure 2

This figure depicts the number of claims in negotiations during the post Action Plan period between March 2008 to March 2012. The number of claims negotiated is indicated on the "Y" axis and the "X" axis indicates the point in time used to measure in March of each year between 2009 and 2012. In 2008, there were 126 claims in the negotiation process, 142 in 2009, 161 in 2010, 162 in 2011, and 280 as of March 2012.

3.1.5 Increase in the number of specific claims resolved through negotiations

The number of claims resolved (settled) through negotiations has not yet increased under the Action Plan.Footnote 14 However, a number of the backlog claims are currently in the negotiation phase, as stated in Section 3.1.4, which may contribute to this outcome in the near future.

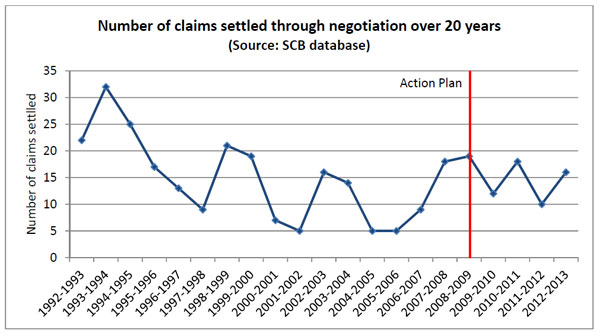

As illustrated in Figure 3, there have been a fairly consistent number of claims reaching a settlement through negotiation pre-and post-Action Plan over a 20 year period.

- The number of claims settled through negotiation between 2008–2009 and 2012–2013 stood at 75, for an average of 15 claims settled per year.

- The number of claims settled through negotiation between 1992-1993 and 2007-2008 stood at 237, for the average number of 14.8 claims settled per year.

Figure 3

Text description of Figure 3

This figure illustrates the number of claims settled through negotiation pre-and post-Action Plan over the 20 year period between 1992-1993 and 2012-2013. The number of claims settled is indicated on the "Y" axis, and the respective fiscal years is indicated over the 20 year period between 1992-1993 and 2012-2013 in the "X" axis. The largest number of claims settled through negotiation in a year was 32 which occurred in 1993-1994. Afterwards, there was a decrease in the number of claims settled through negotiation every year from 1994-1995 until 1997-1998, when only nine claims were settled. The following fiscal year, 1998-1999, saw an increase to 21 settled claims, and then three years of consecutive decreases with only five claims being settled in 2001-2002. In 2002-2003 there was another increase to 16 claims followed by a minor decrease in 2003-2004 to 14. In 2004-2005 and in 2005-2006, five claims were settled each year. In the three year period between 2006-2007 and 2008-2009, there was a moderate increase annually, peaking at 19 claims settled in 2008-2009. After the introduction of the Action Plan in 2008-2009, there were several minor annual fluctuations. However, the number of claims settled through negotiation between 2008–2009 and 2012–2013 stood at 75, for an average of 15 claims settled per year.

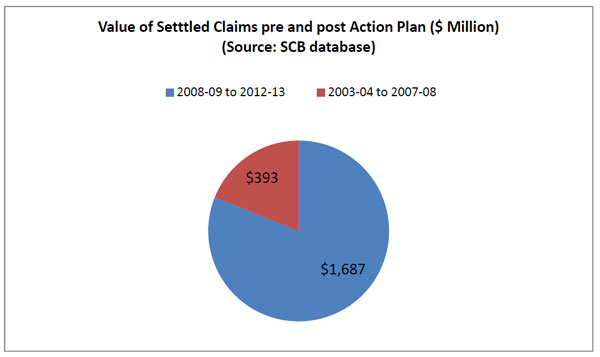

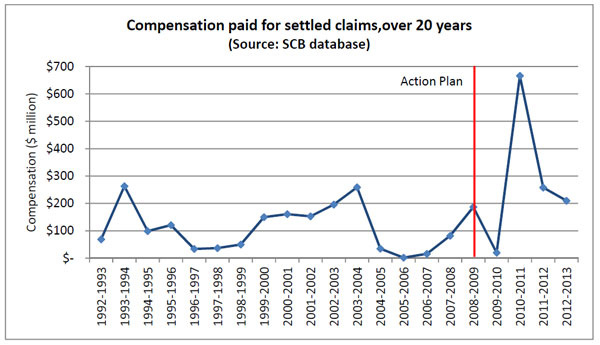

Value of Settled Claims

Under the Action Plan, the total compensation for settled claims has increased significantly. As shown in Figure 4, the total value of claims settled in the five years leading up to the Action Plan was $393 million. Since the Action Plan came into effect, the total value of settled claims has been $1,687 million.

Figure 4

Text description of Figure 4

This figure illustrates in a pie-chart format the value of settled claims pre and post Action Plan in millions of dollars. As demarcated in the red portion of the pie chart, the total value of claims settled in the five years (2003-04 to 2007-08) leading up to the Action Plan was $393 million. The blue portion of the pie chart indicates that since the Action Plan came into effect (2008-09 to 2012-13) the total value of settled claims has been $1,687 million.

Concluded Claims

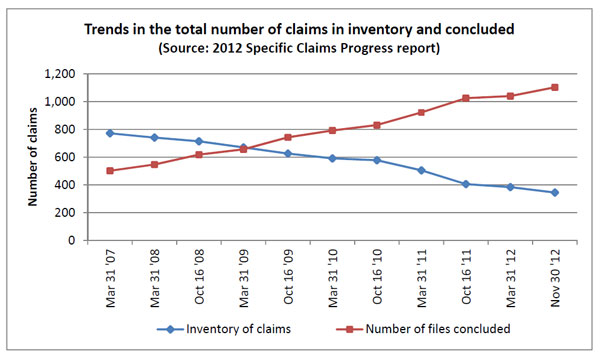

AANDC reports that the overall federal inventory is decreasing and the number of concluded claims is increasing.Footnote 15 The results were tracked at key points from March 31, 2007 to end of November 2012.Footnote 16 As illustrated in Figure 5, the inventory of claims stood at 772 at the end of the fiscal year 2006-2007. By the end of November 2012, this number was reduced to 345. Concluded files stood at 502 at the end of the fiscal year 2006-2007 and by the end of November 2012, it had increased to 1,103.

Figure 5

Text description of Figure 5

This figure illustrates the trends in the total number of claims in inventory and the total number of files concluded. The number of claims settled is indicated on the "Y" axis, and key points from 31 March, 2007 to 30 November, 2012 are indicated in the "X" axis. This graph indicates that the overall federal inventory is decreasing and that the number of concluded claims is increasing. The inventory of claims stood at 772 at the end of the fiscal year 2006-2007. By the end of November 2012, this number was reduced to 345. Concluded files stood at 502 at the end of the fiscal year 2006-2007 and by the end of November 2012, it had increased to 1,103.

Concluded files include those that were: settled through negotiation; resolved through an administrative remedy; where no lawful obligation was found; and, where the file was closed. For the purpose of this evaluation, a distinction is being made between claims that are concluded with finality (complete and final redress of the claim) and claims that may continue to evolve, either by being submitted by First Nations to the Specific Claims Tribunal, or by being submitted to the specific claims process as a new claim. Table 3 presents the breakdown of concluded files.

| Settled through negotiation | 366 | 399 claims concluded with finality | 36% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolved through an administrative remedy | 33 | ||

| No lawful obligation found | 396 | 704 claims concluded without finality | 64% |

| File closed | 308 | ||

| Total | 1,103 | 1,103 | 100% |

Source: AANDC National Summary on Specific Claims |

|||

The first two categories (settled through negotiation or resolved through an administrative remedy) represent claims that are concluded with finality. As of the end of November 2012, there were 399 claims representing 36 percent of all concluded claims. In the case of the other two categories (no lawful obligation found and file closed), during this same time period, there were over 704 claims not concluded with finality representing 64 percent of all concluded files.

As every stage of the specific claims process is voluntary, it is important to note that the specific claim process does not force a claim to be addressed with finality. A First Nation chooses to submit a claim, to negotiate it with Canada, and to decide whether or not to accept a settlement agreement. Furthermore, it is only a First Nation that can make the decision to submit a claim to the Tribunal. Likewise, Canada assesses whether the claim has validity and determines whether or not to enter into negotiations and what would be considered fair compensation.

Therefore, the specific claims process is designed to achieve finality but it does not guarantee that finality will happen in all cases. This is particularly evident by the claims that Canada determined did not disclose an outstanding lawful obligation and the claims falling under the file closure category, which includes, amongst others, claims where a First Nations decide not to accept the settlement offer.Footnote 17 AANDC considers these claims to be concluded but First Nations have not provided Canada with a release and an indemnity with respect to these claims. Therefore, there is a risk that a number of these claims can be submitted to the Specific Claims Tribunal or submitted as a new claim to the specific claims process at any point in the future.Footnote 18

Claims that did not disclose an outstanding lawful obligation

The number of claims where Canada has concluded that they did not disclose an outstanding lawful obligation has increased under the Action Plan. On October 2008, the number of claims did not disclose an outstanding lawful obligation stood at 104. However, since the Action Plan was implemented (up to end of November 2012), Canada concluded that 292 claims did not disclose an outstanding lawful obligation.

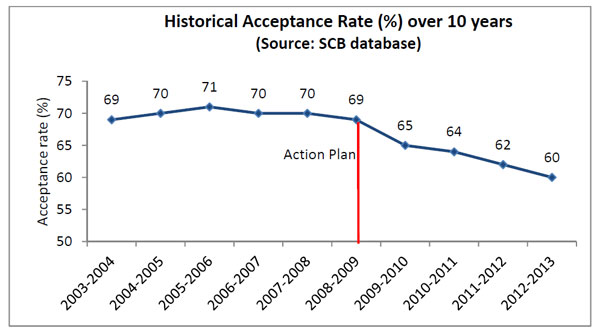

This trend is further reflected in the Historical Acceptance Rate (HAR). The HAR is the proportion of all claims researched and assessed since 1973 where Canada concluded that a claim disclosed an outstanding lawful obligation. Figure 6 illustrates the trend in the HAR for the five-year period pre-Action Plan, as well as the five-year period post-Action Plan. It shows that the HAR has been steadily declining from around 70 percent prior to the Action Plan to around 60 percent in 2012–2013 (2012-13 was not a complete year at the time of the evaluation).

No single factor can be used to explain HAR trends, and the evidence gathered as part of this evaluation does not allow for this report to make conclusions on this matter. Nonetheless, it is important to note the trend since it has a direct impact on the number of claims that may end up before the Specific Claims Tribunal, or that may be submitted to the specific claims process at a later point in time. A decline in the HAR directly correlates to an increase in the number of claims where Canada has concluded that no outstanding lawful obligation was disclosed.

Figure 6

Text description of Figure 6

This figure illustrates the trend in the Historical Acceptance Rate (HAR), in percentage, which is indicated on the "Y" axis, over a ten year period, as indicated on the "X" axis. A vertical line is drawn to indicate the point in time when the Action Plan was introduced. The graph demonstrates the HAR over the five-year period pre-Action Plan, as well as the five-year period post-Action Plan. It shows that the HAR has been steadily declining from around 70 percent prior to the Action Plan to around 60 percent in 2012–2013.

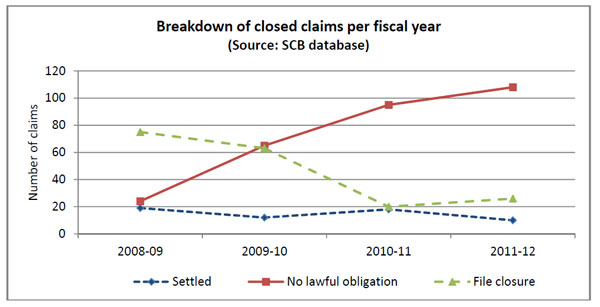

Figure 7 illustrates an increase in the number of post-Action Plan claims under the "no lawful obligation" category, while claims settled through negotiations has remained largely consistent and the number of claims captured in the "file closure"Footnote 19 category has decreased.

Figure 7

Text description of Figure 7

This figure illustrates a breakdown of closed claims per fiscal year by the number of claims that were either settled, where no lawful obligation was found, or where the file was closed. The number of claims closed is indicated on the "Y" axis, and the fiscal years 2008-09 to 2011-12 are indicated on the "X" axis. The graph depicts an increase in the number of post-Action Plan claims under the "no lawful obligation" category, while claims settled through negotiations has remained largely consistent and the number of claims captured in the "file closure" category has decreased, with the trend showing only a very slight increase in 2010-2011 to 2011-2012.

3.2 Achievement of long-term results

In the long term, the Action Plan is expected to contribute to three broad results. Table 4 provides a summary of the degree to which these expected results are being achieved.

| Long-Term Results | Achievement ofResult | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Justice for First Nation claimants | The preconditions for justice and certainty are in place within the specific claims process and the claims that have been settled through negotiations are largely achieving these outcomes. For claims that are not settled through negotiations or Tribunal decisions, it will take time to build the body of law required to assess the extent to which justice and certainty has been achieved. Over time, negotiated settlements, decisions from the Tribunal and the body of law that will emerge from the Tribunal are expected to contribute to a greater level of justice and certainty. |

To be determined |

| 2 | Certainty for government, industry and Canadians respecting disputed lands, resources or relationships | ||

| 3 | Sustainable use of lands and resources | Specific Claim settlements are contributing to the sustainable use of lands and resources, most notably through the Additions to Reserve process. It is still to be determined if the current efforts to improve the Additions to Reserves policy and processes will further support this outcome in relationship to specific claims settlement under the Action Plan. More pressure may be placed on the Additions to Reserves process as the backlog claims currently in the negotiation phase are concluded. |

To be determined |

The long-term outcomes of justice and certaintyare closely tied to the overall objective of the Action Plan, which is to ensure that specific claims are resolved with finality in faster, fairer and more transparent way.

The specific claims process is designed to achieve finality by ensuring that all negotiated settlements and Tribunal decisions include a full and final release of the parties. As stated in the Specific Claims Policy and Process Guide, "A claim settlement must achieve complete and final redress of the claim. First Nations must, therefore, provide the federal government with a release and an indemnity with respect to the claim, and may be required to provide surrender, end litigation or take other steps so that the claim cannot be re-opened at some time in the future."Footnote 20 Therefore, the concept of finality resides in the release that accompanies a negotiated settlement or Tribunal decision.

That said, the body of law emerging from the Tribunal is expected to contribute to a de facto sense of finality for claims that have been addressed, but have not been settled through a negotiated agreement or a Tribunal decision. As the Tribunal renders decisions, it will articulate legal principles on the validity of claims and compensation that will serve to confirm (or refute) Canada's decisions with respect to the status of these claims and consequently, limit any remaining uncertainty related to these claims. Given that, at the time of the evaluation, the Tribunal had rendered only one decision regarding the validity of a single claim, it is too early to assess the extent to which these claims have been addressed with any sense of finality.

The following provides details of the evaluation findings related to each of the long-term results.

3.2.1 Justice

The preconditions for justice for First Nations claimants and Canadians are in place within the specific claims process. This is the result of having a process in place to resolve claims in a timely manner and the existence of an independent Tribunal to assess legal obligations and determine remedies.

Achieving justice in the context of specific claims requires that both parties can fairly and comprehensively address any alleged breach of a lawful obligation. In this context, ensuring a fair and definitive assessment of whether a claim is disclosing an outstanding lawful obligation is a sine qua non condition to its genuine resolution. To this effect, the Action Plan has made significant contributions to the goal of justice, including the establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal. The Tribunal provides an avenue for both parties to obtain a final decision on the validity of a claim. This is particularly commendable, since the Tribunal is allowed to do so regardless of any technical defences such as limitation periods, strict rules of evidence, or the doctrine of laches, something that could not be guaranteed in proceedings before the courts.Footnote 21

In cases where the Tribunal confirms that a claim has disclosed an outstanding lawful obligation, hearings will be held on compensation, unless both parties opt for a negotiated settlement. In cases where the Tribunal concludes that a claim has not disclosed an outstanding lawful obligation, the file is permanently closed. As such, justice does not reside in the nature of a particular decision from the Tribunal (and favour or not of the claimant), but rather, in its legitimacy.

At the time of the evaluation, 65 claims had been settled through negotiation under the Action Plan.Footnote 22 Moreover, one decision had been rendered by the Tribunal, confirming that the associated claim disclosed an outstanding lawful obligation. For both parties and all stakeholders involved in, or related to, these claims, the Action Plan has allowed their claims to be resolved in a timely manner and with finality.

Although other claims have evolved during the same time period, they have not been resolved with the same level of finality. Canada has concluded that 292 claims submitted by First Nations under the Action Plan have not disclosed an outstanding lawful obligation.Footnote 23 These First Nations can accept Canada's assessment, they can resubmit the claim with new evidence, or they take the claim to the Specific Claims Tribunal or to the courts. There is also an undetermined portion of the 308 claims falling under the file closure that can also be submitted to the Tribunal or be submitted to the specific claims process as a new claim. As it is impossible to predict what each First Nation involved in these claims will do, it is appropriate to conclude that a fair amount of uncertainty remains. This is not so much a matter of implementation or procedures, but rather it is a direct consequence of the legislative framework in which the Action Plan operates. The Specific Claims Tribunal Act does not include any time frame or options that could force a claim to reach a final stage.

First Nations have expressed concerns that justice, as initially articulated in the Action Plan, is not being achieved. In submissions to Canada for the five year review of the Action Plan, First Nation organizations were highly critical of how the Action Plan has been implemented and particularity with Canada's current interpretation of the commitments made in Justice at Last. As stated in one of these submissions:

The claimant community is profoundly disappointed and frustrated by Canada's conduct. It does not believe that Canada is honouring its promises in Justice at Last. It has, in a manner that has never been announced or acknowledged, turned the federal processing stage into an arena where Canada appears to be no longer acting in good faith as a fiduciary, but instead is taking every opportunity to merely minimize its liabilities. This approach is inconsistent with the principle of reconciliation that was explicitly embedded into the Specific Claims Tribunal Act.Footnote 24

3.2.2 Certainty

The preconditions to achieve certainty are in place within the Specific Claims process. There is little doubt that the concept of certainty is directly linked to that of justice. For this reason, evaluation findings indicate that the Action Plan has contributed to a greater level of certainty by providing an avenue to resolve a claim with finality, in a timely manner. However, five years into the post-Action Plan period, it has become evident that a significant number of specific claims have been concluded without finality, and may remain in that state for an undetermined period of time.

At its most fundamental level, any specific claims is about uncertainty. By submitting a claim, a First Nation indicates that, in its opinion, an outstanding legal claim exists, such as a breach of a historical treaty or a failure by Canada to uphold an aspect of its fiduciary responsibilities. As a result, the parties must satisfactorily address the claim and, in the meantime, uncertainty remains. Depending on the nature of a claim, a number of stakeholders will be required to manage that uncertainty and await its resolution.

Consequently, when a claim is resolved with finality, certainty is achieved:

- When a settlement is reached through negotiation, certainty is achieved through the release that accompanies the settlement.

- When a First Nation claimant turns to the Tribunal, certainty is achieved through a final and conclusive decision regarding validity and compensation that includes a release of all parties from the claims.Footnote 25

As discussed above, where these two conditions are not met, it is expected that, over time, a greater level of certainty will also be achieved through the body of law that emerges from the work of the Tribunal. Through its assessment of individual claims, the Tribunal will enunciate principles that will guide its decisions, both on validity and (when applicable) on compensation. As with jurisprudence, these principles will become part of the knowledge applied by all stakeholders involved in a claim and, as such, will provide important guidance. The need to further elaborate on this body of law will remain, and the Tribunal will be required to consider different facts and circumstances. While acknowledging this reality, the emerging body of law from the Tribunal is expected to contribute to a greater level of certainty.

3.2.3 Sustainable use of land and resources

Specific claim settlements with a land component give First Nations opportunities to acquire land either by using some or all of their settlement funds to purchase land on the open market or through the transfer of provincial or territorial Crown land. Land-related settlement enables First Nations to apply to have the purchased lands, or provincial or territorial Crown land, given reserve status, either by adding to an existing reserve base or by creating a new one. Regardless of having a land component within the settlement agreement, a First Nation may also purchase land with their compensation and submit an addition to reserve proposal to convert that land to reserve status.

The evaluation found clear examples where the settlement of specific claims has triggered addition to reserve processes. A First Nation may choose to convert private lands purchased with their compensation or federal and provincial Crown lands awarded under the settlement agreement to reserve status. Since the Action Plan came into force, 14 settlement agreements included a land component totalling approximately 200,000 hectares of potential additions to reserves.Footnote 26

While the specific claims process and the additions to reserve process remain distinct from an operational point of view, there is a clear relationship between the two processes. Under the AANDC Policy on Reserve Creation, the conversion of purchased land to reserve status that has resulted from Specific Claims settlements can occur under two categories. First, settlement agreements that contemplate reserve creation are eligible under the legal obligation category. First Nations can use this category to convert purchased land to reserve status only if their settlement agreement identifies an addition to reserve. Otherwise, they can choose to submit a reserve creation proposal under the community additions category. There is no requirement for the settlement agreement to contain a reference to an addition to reserve for First Nations to use this category. However, additional justificationsFootnote 27 are required because additions to reserves under this category are not legal obligations. In addition to these agreements, as noted above, First Nations may choose to use their compensation to purchase private lands and own them in fee simple or convert them to reserve status under a community addition.

The acquisition of land remains a priority for many First Nations. First Nations have noted that from an economic point of view, access to land and natural resources represent one of the most critical issues facing them today .Footnote 28 This was recognized in the political agreement between the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development and the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations signed in parallel to the launching of the Action Plan. The Political was signed in anticipation of a growing number of additions to reserves requests through the impending establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal.Footnote 29

While the Tribunal will, under the proposed Bill, only have jurisdiction to award monetary damages, the parties recognize the particular cultural, spiritual, social and economic significance to First Nations of the lands that have been lost. In situations where a First Nation seeks to re-acquire or replace lands that were the subject of a Specific Claim, the Minister will review with First Nations, policies and practices respecting additions to reserves with a view to ensuring that these policies and practices take into account the situation of bands to which the release provisions of the proposed Specific Claims Tribunal legislation apply. In particular, the Minister will provide priority to additions to reserve of lands affected by the consequences of the release provisions in the legislation or to lands required to replace them.Footnote 30

Efforts to reform the Additions to Reserves policy and process are underway and include creating a new Additions to Reserves category entitled "Tribunal Decisions" for land proposal resulting from positive decisions of the Tribunal. As for settlements under the Action Plan, it is still to be determined how these efforts to improve the Additions to Reserves policy and process will affect specific claim settlements and in particular the long-term result of sustainable use of lands and resources. Moreover, it is anticipated that more pressure may be placed on the Additions to Reserves process as the backlog claims currently in the negotiation phase are concluded.

4. Evaluation Findings: Efficiency and Economy

The evaluation looked for the demonstration of efficiency and economy within the Action Plan.

4.1 Appropriateness and efficiency of process

Practices and procedures are in place to cover all aspects of the claim process and funding is currently in place to ensure its sustainability. To facilitate the implementation of the Action Plan, AANDC has adopted a number of practices and procedures that cover both the specific claims process and hearings before the Tribunal. Every step of the specific claims process is now supported through practices and procedures that cover the early review (to determine whether the minimal standard has been met), the research and assessment stage, legal opinions, negotiation, and settlement. These findings are supported by the recent internal audit, which concluded that AANDC has implemented key governance and operational processes to support the efficient and effective delivery of required services and support to the Specific Claims Process.Footnote 31

These efficiencies have contributed to an increase in the number of negotiations taking place, to the settlement of 65 claims during the post-Action Plan period, and to the fact First Nations have received more than $1 billion in compensation. These achievements are evidence of success. The Action Plan has addressed two of the most fundamental concerns voiced by First Nations over the years concerning the specific claims process. First, it established the Tribunal, an independent adjudicative body that can assess the validity of a claim as well as determine the compensation to be provided when applicable. Second, it addressed concerns regarding the timeliness of the process by accelerating the assessment and negotiation of claims.

However, it is still too early to determine if the efficiency of the process is appropriate to allow for the Action Plan's objective (resolving claims with finality) and long-term results (justice, certainty, and sustainable use of lands and resources) to be achieved.

4.2 Policy or process obstacles

There are a number of factors within the specific claims process that are beyond the control of AANDC and the Department of Justice that can impact the ability to meet the three-year timeframe for negotiations. To address these issues, AANDC has created very clear and efficient processes to facilitate the participation of other parties. These processes have largely been successful at meeting timelines as demonstrated by the progress in addressing the backlog, the increase in negotiation tables and the number of claims resolved. Nonetheless, these factors do create pressure on the process and have the potential to delay negotiations. These include:

- For settlements higher than $7 million, financial mandates must be approved through a Treasury Board Submission. While coordinating efforts are undertaken within AANDC and between AANDC and central agencies, there may be delays in getting such a submission approved.

- The same issue applies to settlements beyond $150 million, which require Cabinet approved financial mandates and final Cabinet approval (in addition to AANDC's internal approvals).

- Depending on the nature of the claim, provincial governments may be involved in the negotiation and settlement of a claim. These provincial authorities do not necessarily operate at a pace equivalent to that of the specific claims process and they are not subject to the framework established by the Specific Claims Tribunal Act. Furthermore, delays can be caused by approval processes within provincial governments.

- The three-year time frame for negotiations start on the date the Minister notifies the First Nation in writing that the claim has been accepted for negotiation. Negotiations will not start however until the Minister has received evidence, such as a Band Council Resolution, stating that the First Nation is prepared to enter into negotiations on the basis set out in the notification of acceptance.

4.3 Operational and policy challenges linked to the Tribunal