Evaluation of Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities

Final Report

Date : April 2013

Project Number: 1570-7/11003

PDF Version (523 Kb, 86 Pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| AFN |

Assembly of First Nations |

| BCR |

Band Council Resolution |

| CLCA |

Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement |

| CRF |

Consolidated Revenue Funds |

| DPR |

Departmental Performance Report |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| ERS |

Estate Reporting System |

| FNOGMMA |

First Nations Oil and Gas and Moneys Management Act |

| HQ |

Headquarters |

| IMETA |

Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities |

| PCD |

Per Capita Distribution |

| RCMP |

Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| TAPE |

Treaty Annuities Payment Experience |

| TFMS |

Trust Fund Management System |

| TPS |

Treaty Payment System |

Executive Summary

Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities (IMETA) is the only remaining component of Managing Individual Affairs portfolio that had not been previously identified for evaluation and was included in the Department's evaluation plan for 2012–13 to improve coverage. IMETA components included in this evaluation are defined below:

Band Moneys are capital and revenue moneys that are generated from reserve land and held in trust on behalf of First Nations by the Government of Canada in its Consolidated Revenue Fund. The Indian Moneys program reviews expenditure requests submitted by band councils to ensure due diligence, eligibility under the Indian Act and that proposed expenditures will benefit the band and its members.

Living Estates, involves the administration of assets of minors and dependant adults that are living on reserve. Upon the identification a dependent adult by provincial authorities, the Department identifies a third-party administrator or, where one cannot be identified, acts as the administrator of last resort.

Decedent Estates provides for the administration of the estates of deceased First Nation individuals who were ordinarily resident on reserve. Upon notification of death, the Department identifies a third-party administrator or, where one cannot be identified, acts as the administrator of last resort. The Decedent Estates program also offers information and capacity development initiatives such as will preparation kits and workshops.

Treaty Annuities are payments made to First Nations to honour obligations set out in historical treaties. The treaties provide for an annual cash payment, ordinarily distributed at treaty events or by individual cheque. The Treaty Annuities Payment Experience enables volunteers (primarily Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) employees at Headquarters) to assist with regional treaty events.

As demonstrated by the program descriptions above, Band Moneys, Living Estates, Decedent Estates and Treaty Annuities vary drastically in target population, administration and outputs. As a result, each component was treated separately in a dedicated section of this report. Key findings, conclusions and recommendations relating to each area are presented below.

- Note: This evaluation does not cover estates management for minors, adoptees or missing persons. Additionally, it does not cover the management of suspense accounts, which are created when cash receipts cannot be directly credited to a First Nation or individual account.

Band Moneys

The evaluation found that the relevance of Band Moneys is primarily driven by high usage of Band Moneys; a lack of workable alternatives that would allow First Nations to access their revenue and capital outside the Indian Act; and legislation and obligations in the Indian Act.

The evaluation observed that the close linkage between Band Moneys and the Indian Act has resulted in an administration design focussed on ensuring compliance. It appears that the evolving needs of First Nations, such as the desire to invest Band Moneys in emerging economic opportunities are restrained by administrative processes designed to serve the administrative and legislative responsibilities of the Department. The rigidity of the Band Moneys program is reflected in the lack of alignment with federal and departmental priorities relating to improved transparency, self-sufficiency and economic development.

According to the findings, Band Moneys has been successful in ensuring departmental responsibilities in the Indian Act have been achieved, and the processes in place contribute to improved decision making and good governance in First Nations. However, the impact of expenditures on members cannot be determined through existing reporting.

Findings suggest that program responses to the May 2010 Audit of Trust Accounts has contributed to improvements in efficiency and economy, but concluded that further improvements could be achieved through training and increased communication. Additionally, the implementation of a viable alternative to Band Moneys could result in significant reductions in departmental administration costs. Transitioning the top twenty bands (in terms of expenditures and transactions) to a Band Moneys alternative would also reduce the amount of interest paid by the Government of Canada.

Specific recommendations relating to Band Moneys include the following:

Recommendation # 1:

- Explore the development of a workable alternative to Band Moneys that would provide First Nations access to funds in the Consolidated Revenue Funds outside the constraints of the Indian Act and present proposed alternative to the Strategic Policy Committee.

Recommendation # 2:

- Any changes to Band Moneys and alternatives be designed to increase the transparency of Band Moneys expenditures to members, better support access to capital for economic development and promote greater self-sufficiency.

Recommendation # 3:

- That AANDC revise the Manual for the Administration of Band Moneys to reflect current policy and modern practices.

Recommendation # 4:

- Facilitate a discussion with First Nations on how to report back to members in a clear and useful manner on Band Moneys expenditures.

Living Estates

Living Estates continues to be relevant as it supports the fulfillment of federal obligations to protect vulnerable individuals under its jurisdiction. While some problems have been encountered in confirming jurisdiction over dependent adults, findings reveal that the program has successfully identified administrators in each case. A lack of data makes it impossible to confirm the achievement of other outcomes on a national scale as it is only possible to assess impacts where the Department is acting as the administrator, or in regions where monitoring of non-departmental administrators is taking place.

There is wide variation in the delivery of Living Estates across the country. This is partly due to differing perspectives on the "administrator of last resort" policy. Some regions are concerned that the policy exposes vulnerable individuals and the Minister to increased risk because of a lack of monitoring of non-departmental administrators. As a result, these regions have adapted the program delivery to address their concerns. British Columbia has also taken steps to develop ties with the provincial public trustee, re-engineer processes, eliminate backlog, provide training and workshops to First Nations and monitor non-departmental administrators. The evaluation concluded that improvements in efficiency and economy could be achieved on a national scale through the sharing of lessons learned and best practices between regions and with Headquarters (HQ). Better use of the Estates Reporting System would also result in improved performance measurement.

Specific recommendations relating to Living Estates include the following:

Recommendation # 5:

- Develop policies and procedures for Living Estates to identify dependent adults and confirm AANDC jurisdiction.

Recommendation # 6:

- Examine the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort" policy for Living Estates.

Recommendation # 7:

- Examine IMETA HQ's relationship with regions in order to provide more consistent and timely support for the administration of Living Estates.

Recommendation # 8:

- Ensure a standard approach to data entry into the Estates Reporting System in order to generate more reliable data for program management.

Decedent Estates

The Decedent Estates program continues to be relevant due to federal obligations towards First Nations, the need for estates services and capacity building and the Crown's interest in reserve land. The evaluation revealed that Decedent Estates has achieved some success protecting and securing assets, but was unable to conclude on the achievement of other outcomes due to data shortages and inconsistencies. Contributing to the lack of performance data is the "administrator of last resort" policy, which does not support the monitoring of third-party administrators.

Capacity development of First Nations was identified by some as the single most effective way to improve program effectiveness and efficiency, however, the evaluation revealed an inconsistent approach to First Nation training and low participation in training sessions. Sharing of lessons learned and best practices, such as the Minimum Value Policy from British Columbia, between regions was advanced as a strategy to improve efficiency and economy. Further analysis of efficiency and economy was not possible due to incomplete and/or inaccurate data in the Estates Reporting System.

Specific recommendations relating to Decedent Estates include the following:

Recommendation # 9:

- Revisit the policy of securing assets in Decedent Estates to identify and mitigate risks such as addressing delays in the notification of death and possible policy conflicts with existing cultural practices.

Recommendation # 10:

- Develop a strategic approach to capacity development to increase effectiveness and efficiency of Decedent Estates with appropriate measurements to monitor success.

Recommendation # 11:

- Examine the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort" policy in the administration of Decedent Estates.

Recommendation # 12:

- Explore the feasibility of adopting and implementing the British Columbia Minimum Value Policy for Decedent Estates on a national scale.

Treaty Annuities

Treaty annuity payments are driven by the continued need for Canada to honour treaties and the high demand for treaty events and payments. The findings reveal that the treaty annuities payment program has been successful in distributing the majority of annuity payments owed. However, the evaluation found that the Treaty Annuities Payment Experience did not adequately respond to regional delivery needs. Overall, while AANDC staff believe that the treaty annuity payment process establishes trust, and contributes to good relations between Canada and First Nations, it is not known at this time if First Nations share the same perspective.

Similar to the Estates programs, the evaluation concluded that improvements to efficiency and economy could be achieved by sharing and implementing best practices to reduce costs associated with the delivery of treaty annuities and improved data.

Specific recommendations relating to Treaty Annuities include the following:

Recommendation # 13:

- Revisit and revise as appropriate the Treaty Annuities Payment Experience to better serve regional needs.

Recommendation # 14:

- Explore options for dealing with resource shortages during the treaty payment season, including making participation in treaty events mandatory to regular duties of all Individual Affairs staff.

Recommendation # 15:

- Refine the Treaty Payment System (TPS) data collection in order to facilitate more effective program management and synchronize the TPS with the Estates Reporting System in order to improve the reliability of the data overall.

Recommendation # 16:

- Coordinate regular forums among Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities regional and HQ staff to provide opportunities for information exchange, sharing of best practices and lessons learned.

Management Response / Action Plan

Evaluation of Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities

Project #: 1570-7/11003

A working group comprised of representatives from the Resolution and Individual Affairs (RIA) Sector and the Regional Operations (RO) Sector will be convened in spring 2013 to respond to evaluation findings and ensure that the regional perspective is considered in implementing the Action Plan.

| Recommendation | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Branch) |

Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Explore the development of a workable alternative to Band Moneys that would provide First Nations access to funds in the CRF outside the constraints of the Indian Act and present proposed alternative to the Strategic Policy Committee. | After exploring options regarding Indian Moneys, RIA has drafted an optional policy allowing for the transfer of all of a First Nation's current and future capital moneys pursuant to Section 64(1)(k) of the Indian Act. The policy will be finalized in 2013. | Director IMETA (RIA) | December 2013 |

| 2. Any changes to Band Moneys and alternatives, be designed to increase the transparency of Band moneys expenditures to members, better supports access to capital for economic development and promote greater self-sufficiency. | The new 64(1)(k) policy will include requirements that trust arrangements provide for reporting to membership on the management of the trust. | Director IMETA (RIA) | December 2013 |

| 3. That AANDC revise the Manual for the Administration of Band Moneys to reflect current policy and modern practices. | The new 64(1)(k) policy will include a requirement that trust arrangements have guidelines on capital encroachment. IMETA will ensure that policies, directives and procedures are aligned with the Indian Act. |

Director IMETA (RIA) | December 2013 |

| 4. Facilitate a discussion with First Nations on how to report back to members in a clear and useful manner on Band Moneys expenditures. | The new 64(1)(k) policy will include requirements that trust arrangements include provisions regarding accountability and reporting to the membership for moneys expended out of the trust. | Director IMETA (RIA) |

December 2013 |

| 5. Develop policies and procedures for Living Estates to identify dependent adults and confirm AANDC jurisdiction. | The Manual for the Administration of Property Pursuant to Section 51 of the Indian Act was updated and circulated in August 2012. The new edition clarifies how to determine and confirm AANDC jurisdiction. |

Director IMETA (RIA) | Completed |

| RIA, in collaboration with regions, will pursue the development of information sharing agreements with provinces and territories with a view to clarifying jurisdictional issues and identifying dependent adults who are subject to the Minister’s legislative authority. | March 2014 | ||

| The joint RIA-RO working group will establish a community of practice on living and decedent estates to identify implementation strategies to support the application of policies and procedures outlined in the manual on an ongoing basis. The community of practice will also be mandated to explore alternatives to the estates regime with a view to improve services to clients. Online options will be explored such as using GC Pedia, video conferencing and other available technologies. | March 2014 | ||

| 6. Examine the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort" policy for Living Estates. | The new edition of the Manual for the Administration of Property Pursuant to Section 51 of the Indian Act provides clearer direction with respect to AANDC's responsibility to monitor the administration of property of a dependent adult when a non-departmental administrator is appointed. | Director IMETA (RIA) | Completed |

| The joint RIA-RO working group will assess the effectiveness and appropriateness of the policy and develop implementation strategies to guide regional officers. | March 2014 | ||

| The working group will also review existing agreements between various regions (Manitoba, British Columbia and Northwest Territories) and their respective Provincial Public Guardians and Trustees as well as other potential alternatives. The working group will explore the cost-effectiveness and feasibility of encouraging the development of similar agreements or alternatives nationally | March 2014 | ||

| 7. Examine IMETA HQ's relationship with regions in order to provide more consistent and timely support for the administration of Living Estates. | Establish monthly training and information teleconferences between IMETA and regions focused on specific topics. | Director IMETA (RIA) | June 2013 |

| The joint RIA-RO working group will review the management systems and procedures in place in each region, identify best practices and draw upon this analysis to propose additional strategies to resolve the communication gap between regions and IMETA. Timely and consistent communications will then be supported and maintained through the community of practice on living and decedent estates on an ongoing basis. | March 2014 | ||

| 8. Ensure a standard approach to data entry into the Estates Reporting System in order to generate more reliable data for program management. | IMETA is currently working with the Indian Registration System (IRS) re-development team with a view to preparing the Estates Reporting System for integration in the new IRS system. | Director IMETA (RIA) | Ongoing |

| The joint RIA-RO working group will identify areas requiring enhancements to enable regional officers and AANDC managers to use the Estates Reporting System as an effective case management, reporting and monitoring tool. The working group will mandate the community of practice on living and decedent estates to explore strategies to encourage a national standard approach to data entry. | March 2014 | ||

| 9. Revisit the policy of securing assets in Decedent Estates to identify and mitigate risks such as addressing delays in the notification of death and possible policy conflicts with existing cultural practices. | The joint RIA-RO working group will develop strategies to mitigate the risks related to delays of notification of death and other impediments to securing assets. |

Director IMETA (RIA) | March 2014 |

| 10. Develop a strategic approach to capacity development to increase effectiveness and efficiency of Decedent Estates with appropriate measurements to monitor success. | The joint RIA-RO working group will draw upon current examples of capacity building initiatives, such as the Memorandum of Understanding with the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, and wills workshops, to explore the feasibility of developing a sustainable and accessible approach to capacity development for estates management in First Nations communities nationally. | Director IMETA (RIA) | December 2013 |

| 11. Examine the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort" policy in the administration of Decedent Estates. | The joint RIA-RO working group will engage with Land and Economic Development to assess the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort policy" and explore strategies to ensure the proper legal distribution of the reserve land assets of an estate. | Director IMETA (RIA) | March 2014 |

| 12. Explore the feasibility of adopting and implementing the British Columbia Minimum Value Policy for Decedent Estates on a national scale. | Finalize and implement the British Columbia Minimal Value Estates and Expedited Section 50 Sale policies for Decedent Estates on a national scale. | Director IMETA (RIA) | Completed |

| Other tools identified by and based on best regional practices are currently undergoing a risk analysis. The joint RIA-RO working group will review the outcome of this analysis and recommend strategies for implementation. | March 2014 | ||

| 13. Revisit and revise as appropriate the Treaty Annuities Payment Experience to better serve regional needs. | Since they are better placed to recruit individuals to meet their needs, regional offices will be responsible for managing the Treaty Annuity Payment Experience. A letter to the regional directors general was sent on October 19, 2012, to advise the regions that RIA will no longer be involved in the Treaty Annuities Payment Experience. | Director IMETA (RIA) | Completed |

| 14. Explore options for dealing with resource shortages during the treaty payment season, including making participation in treaty events mandatory to regular duties of all Individual Affairs staff. | A workshop with regions and other sectors was held in January 2012 to identify current issues with respect to the effective delivery of treaty annuities to First Nations individuals. The joint RIA-RO working group will review and confirm key issues identified and recommend sustainable solutions as well as explore alternatives to the current service delivery model. |

Director IMETA (RIA) | March 2014 |

| 15. Refine the TPS data collection in order to facilitate more effective program management and synchronize the TPS with the Estates Reporting System in order to improve the reliability of the data overall. | IMETA has begun engaging the IRS re-development team with a view to preparing the TPS for integration in the new IRS integrated platform. | Director IMETA (RIA) | Ongoing |

| The joint RIA-RO working group will identify necessary improvements to better support service delivery in the regions and support management in their reporting requirements. | March 2014 | ||

| 16. Coordinate regular forums among Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities regional and headquarters staff to provide opportunities for information exchange, sharing of best practices and lessons learned. | The joint RIA-RO working group will recommend approaches to improve the communications between IMETA and the regions. The community of practice on treaty annuity payments will be mandated to foster and maintain sustainable, timely and consistent communications. It will also promote the sharing of best practices with a view to developing standardized approaches to the administration of treaty annuity payments. | Director IMETA (RIA) | March 2014 |

Recommendations

In light of the analyses and findings, it is recommended that Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada support the implementation of the following recommendations:

Recommendation # 1: Explore the development of a workable alternative to Band Moneys that would provide First Nations access to funds in the Consolidated Revenue Fund outside the constraints of the Indian Act and present proposed alternative to the Strategic Policy Committee.

Recommendation # 2: Any changes to Band Moneys and alternatives be designed to increase the transparency of Band Moneys expenditures to members, better support access to capital for economic development and promote greater self-sufficiency.

Recommendation # 3: That AANDC revise the Manual for the Administration of Band Moneys to reflect current policy and modern practices.

Recommendation # 4: Facilitate a discussion with First Nations on how to report back to members in a clear and useful manner on Band Moneys expenditures.

Recommendation # 5: Develop policies and procedures for Living Estates to identify dependent adults and confirm AANDC jurisdiction.

Recommendation # 6: Examine the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort" policy for Living Estates.

Recommendation # 7: Examine IMETA HQ's relationship with regions in order to provide more consistent and timely support for the administration of Living Estates.

Recommendation # 8: Ensure a standard approach to data entry into the Estates Reporting System in order to generate more reliable data for program management.

Recommendation # 9: Revisit the policy of securing assets in Decedent Estates to identify and mitigate risks such as addressing delays in the notification of death and possible policy conflicts with existing cultural practices.

Recommendation # 10: Develop a strategic approach to capacity development to increase effectiveness and efficiency of Decedent Estates with appropriate measurements to monitor success.

Recommendation # 11: Examine the appropriateness of the "administrator of last resort" policy in the administration of Decedent Estates.

Recommendation # 12: Explore the feasibility of adopting and implementing the British Columbia Minimum Value Policy for Decedent Estates on a national scale.

Recommendation # 13: Revisit and revise as appropriate the Treaty Annuities Payment Experience to better serve regional needs.

Recommendation # 14: Explore options for dealing with resource shortages during the treaty payment season, including making participation in treaty events mandatory to regular duties of all Individual Affairs staff.

Recommendation # 15: Refine the Treaty Payment System data collection in order to facilitate more effective program management and synchronize the Treaty Payment System with the Estates Reporting System in order to improve the reliability of the data overall.

Recommendation # 16: Coordinate regular forums among Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities regional and Headquarters staff to provide opportunities for information exchange, sharing of best practices and lessons learned.

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed by:

Andrew Saranchuk

A/Assistant Deputy Minister

Resolution and Individual Affairs

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on April 25, 2013.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The Evaluation of the Indian Moneys, Estates and Treaty Annuities (IMETA) was included in the Department's evaluation plan for 2012–13 to improve evaluation coverage of the Managing Individual Affairs program activity. Managing Individual Affairs is responsible for the following:

- Provisions of the Indian Act concerning the administration of IMETA.

- Registration and band membership.

- Administering the moneys management portion of the First Nations Oil and Gas and Moneys Management Act (FNOGMMA).

- Overseeing federal obligations outlined in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement implemented on September 19, 2007, and other federal initiatives that address the impact of residential schools on Aboriginal people in Canada.Footnote 1

An evaluation of FNOGMMA and Registration Administration were completed in September 2010. An evaluability assessment of the Residential School Resolution conducted in 2009 concluded that an evaluation was not required under the Treasury Board Evaluation Policy; there was no precedent to evaluate court-ordered settlements; and there was already significant monitoring through bi-annual reporting to Treasury Board and the court. As a result, there are no further evaluation commitments for the Residential School Resolution.

As shown above, IMETA is the only component of Managing Individual Affairs that has not been previously evaluated. The Indian Act defines Indian Moneys as "all moneys collected, received or held by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of Indians or bands". For the purposes of this evaluation, Indian Moneys includes individual moneys, band moneys and moneys held in suspense accountsFootnote 2 each of which is further defined below:

Individual Moneys involves the creation and maintenance of individual accounts for per capita distributions and estates management. Living Estates, more commonly referred to as a "trusteeship", involves the administration of assets of minors and dependant adults that are living on reserve. Upon the identification a dependent adult by provincial authorities, the Department identifies a third-party administrator or, where one cannot be identified, acts as the administrator of last resort. In this evaluation, the term "dependent adult" is used instead of "mentally incompetent" as defined in the Indian Act.

Decedent Estates provides for the administration of the estates of deceased First Nation individuals who were ordinarily resident on a reserve. Upon notification of death, the Department identifies a third-party administrator or, where one cannot be identified, acts as the administrator of last resort. The Decedent Estates program also offers information and capacity development initiatives such as will preparation kits and workshops.

Treaty Annuities are also considered individual moneys as payments are made to individual band members. The Treaty Annuities Program administers the payment of annuities under various treaties signed by First Nations (Robinson-Huron, Robinson-Superior and numbered treaties 1 to 11) with the Crown. The treaties provide for an annual annuity payment to be paid in cash, ordinarily distributed at treaty events or by individual cheque. The Treaty Annuities Payment Experience (TAPE) program is a component, which enables volunteers (primarily Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) employees) to assist with regional treaty events.

Band Moneys are capital and revenue moneys held in separate interest-bearing accounts under the name of a particular First NationFootnote 3. Band Moneys are generated from reserve land that belongs collectively to the band. The Indian Moneys program reviews expenditure requests submitted by band councils to ensure due diligence, eligibility under the Indian Act and that proposed expenditures will benefit the band and its members.

Suspense Accounts are created when cash receipts cannot be directly credited to a First Nation or individual account. Each region has one band moneys suspense account. Moneys placed in suspense accounts may include receipts for unidentified First Nations or persons, receipts for moneys under litigation and amounts received for unapproved or expired leasesFootnote 4. Regional offices monitor suspense accounts to ensure appropriate bands or individual accounts are creditedFootnote 5.

As demonstrated by the descriptions above, Band Moneys, Living Estates, Decedent Estates and Treaty Annuities vary drastically in target population, administration and outputs. As a result, each component is treated in separate sections of this report.

The evaluation of IMETA was carried out primarily by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB). Castlemain Management Consulting was engaged to complete the literature review for Living and Decedent Estates and to conduct a study of alternatives to Band Moneys.

1.2 Program Resources

Table 1.1 shows costs for IMETA for the evaluation period from 2006-07 to 2010-11.

| Actuals | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band Moneys | Vote 1 (Operations and Maintenance) ($) | 952,323 | 958,980 | 1,015,836 | 1,522,875 | 572,000 | 5,022,014 |

| Vote 10 (Grants and contributions) ($) | - | - | 172,000 | 456,000 | 506,000 | 1,134,000 | |

| Total for Band Moneys ($) | 952,323 | 958,980 | 1,187,836 | 1,978,875 | 1,078,000 | 6,156,014 | |

| Living and Decedent Estates | Vote 1 (Operations and Maintenance) ($) | 1,143,091 | 1,405,765 | 1,764,020 | 1,891,553 | 3,380,512 | 9,584,941 |

| Vote 10 (Grants and contributions) ($) | 145,886 | 135,886 | 60,886 | 275,900 | 290,900 | 909,458 | |

| Total for Estates ($) | 1,288,977 | 1,541,651 | 1,824,906 | 2,167,453 | 3,671,412 | 10,494,399 | |

| Treaty Annuities | Vote 1 (Operations and Maintenance) ($) | 328,193 | 425,861 | 544,742 | 723,996 | 1,146,850 | 3,169,642 |

| Vote 10 (Grants and Contributions) ($) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total for Treaty Annuities ($) | 328,193 | 425,861 | 544,742 | 723,996 | 1,146,850 | 3,169,642 | |

| Total | 2,569,493 | 2,926,492 | 3,557,484 | 4,870,324 | 5,896,262 | 19,820,055 |

At the writing of the final report, a separate cost breakdown for the delivery of Living and Decedent Estates was not available. Of note is that costs for Band Moneys have stayed relatively stable and that both the Estates and Treaty Annuities programs have seen marked increases in costs – two times and 3.5 times respectively.

An additional cost for Band Moneys that is not captured in the table above is the interest paid. The average annual balance for Band Moneys for the duration of the evaluation was approximately $1,022,698,294.Footnote 6 As the Government of Canada holds the funds and does not invest them, it must pay interest on this balance. In 2011-12, approximately $27,938,826 was paid in interest for Band Moneys.Footnote 7

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

This evaluation looked at Indian Moneys, which includes Band Moneys, Living and Decedent Estates and Treaty Annuities. The evaluation examined activities undertaken over a five-year period between fiscal years 2006-2007 through 2010-2011. The Terms of Reference were submitted to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 20, 2011. The modifications required by the Committee were reflected in the methodology report, approved by the Committee on September 23, 2011. Research was conducted between October 2011 and April 2012.

This evaluation does not cover individual moneys and programming related to minors, adoptees or missing persons. Nor does it cover the management of suspense accounts.

2.2. Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the Terms of Reference, this evaluation focused on the following issues:

Relevance: including continued need for IMETA, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities and federal and departmental priorities.

Performance: including the extent to which IMETA has achieved expected results and demonstrated efficiency and economy. The evaluation also looked at lessons learned and alternatives.

2.3. Evaluation Methodology

2.3.1 Data sources

The findings and recommendations in this report are based on an analysis of the following data sources:

- Literature reviews: Literature reviews were conducted for each component of IMETA and contributed largely to the examination of relevance. Materials reviewed included special studies, audits, evaluations, reports on plans and priorities and other information pertaining to the origins, purpose, expected results and continued need of IMETA. Government of Canada documents such as the Speech from the Throne, budget documents, official announcements, agreements and joint initiatives were also reviewed to determine program alignment with federal and departmental priorities. The literature review also sought out available information on similar programs and activities in the private and public sectors in provinces, territories and abroad to inform the analysis of best practices and alternatives.

- Document review: A review of documents generated by each program component allowed for the preparation of individual program profiles and contributed to the analysis of effectiveness, efficiency and economy. Examples of documents reviewed include program manuals, year-end reports, program files, information systems, and other analysis or special studies conducted by the programs.

- Key Informant Interviews: A total of 54 interviews were conducted in person or over the phone to solicit individual perspectives on the relevance and performance of IMETA and to contribute to case studies described below. Thirty-seven interviews were with IMETA staff at Headquarters (HQ) and in the regions. Eight interviews were conducted with AANDC staff whose work touches on IMETA. Seven interviews with external experts were conducted for Band Moneys and Living and Decedent Estates and focussed largely on best practices and possible alternatives. Two interviews were conducted with First Nations that had a high volume of Band Moneys transactions. Table 2.1 provides a breakdown of the interviews conducted for each component:

| IMETA Component | Interview Participants | # of Interviews |

|---|---|---|

| BAND MONEYS | IMETA staff from HQ, Alberta and Saskatchewan | 5 |

| Other AANDC staff knowledgeable of Band Moneys, including a departmental historian and representatives from Lands and Environmental Management and Corporate Accounting and Reporting Services | 4 | |

| External experts, mainly lawyers and financial managers, that have worked extensively with First Nations setting up private trust funds | 3 | |

| First Nations that have extensive experience with Band Moneys transactions | 2 | |

| TOTAL FOR BAND MONEYS | 14 | |

| ESTATES (Living and Decedent) |

IMETA staff from HQ, Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia | 20 |

| AANDC representative from Application and Database Development | 1 | |

| External experts (personne at Wikwimekong First Nation and the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne and Professors of Law from the University of Montreal) | 4 | |

| TOTAL FOR ESTATES | 25 | |

| TREATY ANNUITIES | IMETA staff from HQ, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario | 10 |

| TOTAL FOR TREATY ANNUITIES | 10 | |

| ALL | IMETA management at HQ and in Saskatchewan | 2 |

| AANDC representatives from Legal Services | 3 | |

| TOTAL FOR ALL | 5 | |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF INTERVIEWS | 54 | |

Tailored interview guides were prepared for HQ and regional IMETA staff, managers, other AANDC staff, First Nations and external experts. Interview responses were transcribed and analyzed to identify common themes or ideas in responses. Evidence from interviews presented in this report were based on statements from multiple individuals and do not represent the views of one individual.

- Case studies: A number of case studies were completed to look for efficiencies in program delivery across the country and contributed greatly to the development of the program profiles. The Living Estates case study examined program design and delivery and the identification of best practices in all regions. The Decedent Estates case studies reviewed AANDC initiatives to promote the administration of estates by First Nation communities. One Treaty Annuities case study focused on the identification of best practices in Saskatchewan, Ontario, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. A second case study was completed to better understand the TAPE program.

- Study on Alternatives to Indian Moneys: This study identified examples of First Nations trust funds and lessons learned regarding their structure and use. The study looked at different models for trust funds, factors for successful trust management, features of trust fund agreements, qualities of First Nations, which are successfully managing their trust funds and the impact of trust funds on communities. This study contributed to the discussion of best practices and alternatives to Band Moneys.

2.3.2. Source limitations

The methodologies identified above have limitations that must be noted so that the strength of the findings and recommendations of this report can be properly situated.

Document Review: Data available in the Trust Fund Management System (TFMS) is excellent and allowed for significant quantitative analysis to support findings. However, the national information systems for Living and Decedent Estates (Estates Reporting System) and Treaty Annuities (Treaty Payment System) are outdated, poorly designed and contain gaps in information making them unreliable. As a result, many of the findings related to estates and treaty annuities rely on qualitative lines of evidence or quantitative data from one or two regions. Reliable national-level data and gender-specific data are rare.

Furthermore, current reporting of delivery costs is not separated out by individual program component. The need for this information was identified early in the project, but program representatives reported difficulties obtaining costs by component because budgets are assigned to a cluster of activities and resources are shared. Partial information representing the delivery costs for one year or one region was obtained and is presented in the report, however, partial information must be considered as illustrative of a trend and not definitive.

Key Informant Interviews: For Living and Decedent Estates, interviews with IMETA staff were conducted in all regions in order to understand the impact of different approaches to program delivery. For Band Moneys and Treaty Annuities, the strategy was to conduct interviews with IMETA staff in the regions that have the greatest activity; for Band Moneys this was Alberta and Saskatchewan, and for Treaty Annuities interviews with regional staff were scheduled in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario. As a result, the findings related to Band Moneys and Treaty Annuities do not represent a national picture.

The limited involvement of First Nations individuals and organizations in the key informant interviews is also viewed as a weakness in this analysis. Two First Nations were interviewed for Band Moneys, but it was deemed inappropriate to contact bereaving heirs to inquire about their experiences with AANDC Decedent Estates programming or dependent adults regarding Living Estates. For Treaty Annuities, the perspectives of Treaty First Nations were not obtained.

Finally, the discussion of alternatives and best practices relating to Estates could have been enhanced by interviews with Provincial Public Trustees.

2.4. Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Terms of Reference and Methodology Report were developed by EPMRB with input from IMETA representatives in the National Capital Region. EPMRB planned the evaluation, defined methodologies, created evaluation tools, completed literature reviews, scheduled and conducted interviews, designed case studies, reviewed reports, analyzed findings, drafted preliminary findings and recommendations, prepared technical and final reports and reported on progress to Working Group and Management. Castlemain Management Consulting was engaged to complete the Estates literature review and conduct a study of alternatives to Indian Moneys.

A Working Group with representatives from EPMRB and IMETA staff from HQ and the regions was formed to provide advice and guidance on program profiles, logic models, methodologies, evaluation questions, regional visits, preliminary findings and the draft final report. The preliminary findings were also presented to the Directors General Policy Coordination Committee on May 17, 2012.

3. Band Moneys

3.1 Program Profile

This section provides an overview of Band Moneys, including the origins and current functioning of the program, objectives, management, stakeholders, beneficiaries and resources.

3.1.1 Background and description

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Indian Department was under military control and Indian policy was primarily geared to maintaining Indians as military allies or keeping the peace. Early activities included negotiating treaties, paying annuities and the management of funds from the sale of ceded lands. Band Moneys emerged in the early 1800s from the need for accurate record keeping to manage the money generated from the sale, rent, or lease of Indian lands, property and renewable and non-renewable resources, and the accrual of interest.Footnote 8

In the early 19th century, Indian and Band Moneys were invested in England. These funds were later transferred to Canada and invested in various securities such as Provincial Bonds, Municipal Loan Fund Bonds and Grand River Navigation Company stock. The Government preferred that the principal be invested and the interest earned would provide a source of revenue for bands.Footnote 9 By Order in Council passed in 1861, the Province of Upper Canada assumed control over these securities from the Imperial Crown and thereafter Indian and Band Moneys were credited to accounts and held in a "Trust Fund".Footnote 10

The concept of preserving the principal for future generations was introduced in 1839. So important was the preservation of capital that it was also common practice to require the repayment of capital for some expenses with interest. This practice was made official in 1938 – loans could be made to Indian bands for purchase of farm implements, machinery and livestock, fishing and other equipment, grain seed and materials for handicrafts. Sums were paid out of band funds with an interest rate of five percent.Footnote 11

Despite federal interest in protecting capital, by the late 19th century band capital and revenue moneys were being used to support the growing expenses of the Indian Department and the federal government's "civilization program", which can be traced to an 1826 inquiry into the affairs of the Indian Department. This inquiry recommended settling Indians on farms and substituting farming implements and farm stock for the annual presents. Over time, the statutory principles governing the use of capital were frequently amended, continually expanding the list of purposes for which they could be expended.Footnote 12 An amendment to the Indian Act in 1918 allowed expenditure of band money without band consent. Over time, moneys were used to support capital projects, education (including residential schools), the purchase of agricultural implements, salaries for Indian Department officials, and the purchase of goods.

Under the 1951 Indian Act, the Minister could no longer authorize capital and revenue expenditures without the consent of Band Council, however, the Minister remained responsible for determining whether proposed expenditures were permitted under the Indian Act and were to the benefit of band members. There has been no evolution to sections of the Indian Act pertaining to Band Moneys since 1951.

The Indian Act defines Indian moneys as "all moneys collected, received or held by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of Indian or Bands". As title to reserve lands rests with the Crown, all moneys derived from reserve land activities must be collected by the Department and deposited 'in trust' for the benefit of the First Nation for which such lands were set aside.

Band Moneys under Section 62 of the Indian Act are referred in two categories as:

- Capital moneys – derived from the sale of surrendered lands or the sale of the capital assets of a First Nation. These moneys include royalties, bonus payments and other proceeds from the sale of timber, oil, gas, gravel or any other non-renewable resource.

- Revenue moneys – all Indian moneys other than capital moneys. They are derived from a variety of sources, including, but not limited to, the interest earned on band capital and revenue moneys, fine moneys, proceeds from the sale of renewable resources (e.g., crops), leasing activities (e.g., cottages, agricultural purposes) and other commercial ventures.

Band capital and revenue moneys are considered public moneys, not appropriated by Parliament, and are held by the Crown within the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) on behalf of First Nations. Funds are administered by the Minister of AANDC pursuant to sections 18(2), 28(2), 35(1), 37(1), 38(1), 39, 61 to 69 and 104 of the Indian Act. The CRF is the single fund used to receive all moneys collected by Canada.

Band capital and revenue moneys earn a rate of return (interest rate) set by the Governor in Council through an Order in Council. Interest rates are based on Government of Canada bonds having a maturity of ten years or over, using the weekly yields published by the Bank of Canada. Based on the month-end balances in the First Nation's account, interest is calculated quarterly, compounded semi-annually and deposited every six months (April and October) into the First Nation's revenue account.

It is relatively easy for bands to access revenue moneys compared to capital moneys. Under Section 66 of the Indian Act, subject to consent of the Band CouncilFootnote 13, revenue moneys may be spent for any purpose that will promote the general progress and welfare of the band or any member of the band (66(1)) or to assist sick, disabled, aged or destitute Indians and for the burial of deceased indigent members of the band (66(2)). Furthermore, revenue moneys may be spent for a number of reasons, without consent of the band council, including the destruction of insects or pests, to address the potential spread of disease, to provide for premise inspections, to prevent overcrowding of housing, to provide sanitary conditions and to construct and maintain boundary fences. However, spending without band council consent is rarely, if ever, exercised.

In addition, under Section 69 of the Indian Act, bands may gain control over the management and expenditure of their revenue moneys. To do this, they must obtain consent from their membership through a Band Council Resolution (BCR) and submit it to AANDC for review. If all conditions are met, and AANDC approves, an Order in Council is prepared for signature by the Governor General.

The expenditure of capital moneys is more strictly controlled under Section 64(1) of the Indian Act. Permitted expenditures of capital moneys as defined in Section 64(1) of the Indian Act includes items such as: per capita distributions, construction and maintenance of roads, bridges, water courses and boundary fences; the purchase of additional reserve land or interest in land on behalf of a band member; purchase of livestock and farm equipment; construction and maintenance of permanent improvements and works; providing loans; land and property management expenses; construction and financing of housing; and any other purpose approved by the Minister.

Approval of expenditures under sections 64, 66 and 69 has been largely delegated to the regions, however, capital expenditures under Section 64 (1) (d) and (k) must be approved by the Minister. There is no provision in the Indian Act that gives First Nations control over their capital revenues similar to those in Section 69, which gives band control over their revenue moneys. First Nations may gain control over their capital moneys through FNOGMMA, however, to date, no First Nation has been successful in the process for reasons explained later in the report.

The process to access capital and revenue moneys held in the CRF is as follows:

- Formal request: First Nations submit a formal request to spend capital or revenue funds held in the CRF through a BCR.

- Departmental assessment: An initial review of the BCR examines the benefit to members by looking at: proposed costs, impact on account balance and alternative sources of income; socio-economic impacts such as dependence on existing programs and services such as social assistance; possible environmental impacts; legal and other implications; and the annual operating budget where applicable.

Supporting documentation must be provided for capital expenditures under Section 64 and revenue expenditures under Section 66 to enable departmental officials to make an informed decision on the merits of an expenditure request. Requirements depend on the specific purpose and nature of the request.

If the review and assessment are satisfactory, departmental staff must then prepare the appropriate approval documentation with their recommendation for full, partial or conditional approval. - Release of Band Moneys: Once approval has been given, required information is then recorded in the TFMS and made available for the creation of a Payment Obligation Certificate and management approval.

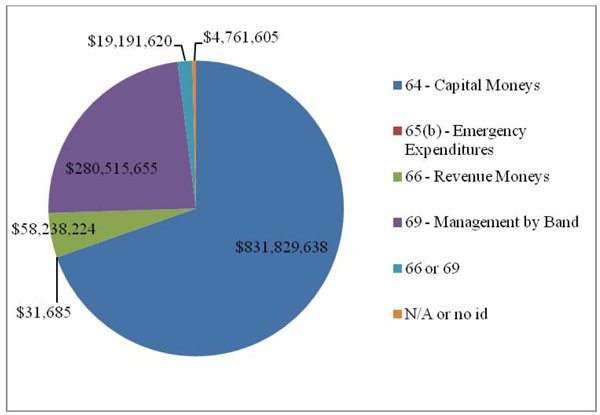

An analysis of the types of expenditures by section of the Indian Act between 2006-07 and 2010-11 reveals that revenue expenditures under Section 66 represent five percent of total expenditures and Section 69 revenue expenditures account for 23 percent of total expenditures. As shown in figure 3.1 below, the majority, or 69 percent, of total expenditures pertain to capital expenditures under Section 64 of the Indian Act.

Figure 3.1 Total amount of payment transactions by section of the Indian Act between 2006-07 and 2010-11.Footnote14

Text alternative for Figure 3.1 Total amount of payment transactions by section of the Indian Act between 2006-07 and 2010-11

The Total Amount of Payment Transactions by Section of the Indian Act between 2006-07 and 2010-11 figure shows a pie chart, which sections representing each of the following: "capital moneys"; "emergency expenditures"; "revenue moneys"; "management by band"; "revenue moneys or management by band"; and "N/A or no ID". Almost 3/4 of the pie chart consists of "capital moneys", with a total of $831 829 638. The second largest section of the pie chart consists of "management by band" which is almost ¼ of the chart with a total of $280 515 655. The third largest section of the chart consists of "revenue moneys", with $58 238 224. The fourth largest section consists of "revenue moneys or management by band", with 19 191 620. The fifth largest section is the category of "N/A or no ID", with $4 761 605. The last and smallest section of the chart is "emergency expenditures", with $31 685.

3.1.2. Objectives and expected outcomes

The immediate outcome identified through the document review and interviews is that Band Moneys capital and revenue expenditures are approved according to the provisions prescribed in the Indian Act. The intermediate outcome is that Band Moneys expenditures benefit bands and their current and future members.

3.1.3. Program management

The IMETA Directorate of the Individual Affairs Branch of the Resolution and Individual Affairs Sector carries out a number of functions related to Band Moneys, however, other areas of AANDC also support or contribute to moneys management activities.

Most administrative and operational responsibilities for the day to day administration of band and individual moneys under the Indian Act have been assigned to the regional offices. Regional director generals are responsible for approval of requests for revenue expenditures under sections 66 and 69 of the Indian Act and approval of requests for capital expenditures (with the exception of those falling under paragraphs 64(1)(d) and (k) of the Indian Act, which remains exclusive for Ministerial approval)Footnote 15.

Regional Band Moneys officers consult and provide advice to First Nations on varying aspects of the administration of Band Moneys. In addition, they analyse expenditure requests, review annual Band Moneys budgets, make recommendations regarding expenditure requests, prepare submissions for granting Section 69 authority to First Nations and review annual audited financial statements.

HQ develops national directives, policies and procedures and training materials related to the administration of Band Moneys. It provides functional advice and training to regions on the implementation of policies and procedures. IMETA HQ also works with sectoral partners and with regions to review expenditure requests, which fall under sections 64(1)(d) and (k) and on recommendations from regions for a First Nation to obtain Section 69 authority over its revenue moneys.

3.1.4 Key stakeholders and beneficiaries

First Nation Communities and Individuals

The primary beneficiaries of Band Moneys are bands with funds held in trust and their members. Bands are responsible for preparing expenditure requests and required documentation for submission to AANDC, making expenditures on behalf of their members and reporting back to AANDC.

Lands Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector

Funds are generated through the sale of renewable resources and non-renewable resources (sand, gravel, timber) and transactions (leases, permits, rights of way), which are administered by the Lands and Economic Development Sector. Regional and district Lands staff ensure the collection of all moneys prescribed in agreements. These funds are then deposited into the CRF and administered by AANDC pursuant to the Indian Act.

Indian Oil and Gas Canada

The Indian Oil and Gas Act and regulations provide the authority for Indian Oil and Gas Canada to manage oil and gas resources on First Nation lands. Under this legislation, Indian Oil and Gas Canada assists First Nations in negotiating, issuing and managing oil and gas resources (permits, leases, agreements). It also verifies oil and gas production and provides forecasts of projected royalties. Resulting revenues from oil and gas royalties, bonuses, etc., are deposited into the CRF to the credit of applicable First Nations and are administered by AANDC pursuant to the Indian Act.

Corporate Accounting and Material Management Branch, Chief Financial Officer

The Chief Financial Officer is responsible for corporate accounting and financial administration. It manages and maintains the TFMS and is primarily responsible for the maintenance and coordination of semi-annual deposits of interest into revenue accounts and account policy and procedures.

Legal Services Unit, AANDC

Legal Services and the Department of Justice provide advice on how expenditures could directly or indirectly affect the Minister's fiduciary obligations in relation to the overall administration of Band Moneys.

3.2. Findings – Relevance

There are three measures of relevance: continued need, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities and alignment with federal and departmental priorities. The evaluation found that the relevance of Band Moneys is primarily driven by high usage of Band Moneys; a lack of workable alternatives that would allow First Nations to access their revenue and capital outside the Indian Act, and;legislation and obligations in the Indian Act.

The close linkage between Band Moneys and the Indian Act has resulted in an administration design focussed on ensuring compliance. As a result, the evolving needs of First Nations, such as the desire to invest Band Moneys in emerging economic opportunities are constrained by administrative processes designed according to the requirements of the Indian Act. The rigidity of Band Moneys is also reflected in its lack of alignment with federal and departmental priorities.

Finding # 1: Continuing need is confirmed by the high volume of Band Moneys transactions and difficulties gaining access to Band Moneys through other mechanisms.

Between 2006-07 and 2010-11, there were a total of 5019 payment transactions involving the expenditure of $1.2 billion in Band Moneys.

| Region | Number of Bands in Region with Payments |

Number of Payment Transactions |

Total Amount of Payment Transactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northwest Territories | 1 | 3 | $243,100.00 |

| Atlantic | 11 | 78 | $4,509,344.15 |

| Quebec | 7 | 39 | $10,413,356.66 |

| Ontario | 36 | 167 | $26,087,759.10 |

| Manitoba | 10 | 26 | $1,289,822.30 |

| Saskatchewan | 55 | 1297 | $130,422,953.47 |

| Alberta | 39 | 2841 | $953,394,114.40 |

| Yukon | 3 | 5 | $3,554.61 |

| British Columbia | 106 | 563 | $74,452,467.13 |

| Total | 268 | 5019 | $1,200,816,471.82 |

As the Oil and Gas Sector accounts for a significant percentage of capital moneys, the majority of funds are held by bands in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Table 3.2 shows that Alberta and Saskatchewan were the source of most payment transactions and expenditures. Alberta accounted for 57 percent of total payment transactions and 79 percent of total expenditures. Saskatchewan accounted for 26 percent of total payment transactions and 11 percent of total expenditures. Further, 17 of the top 20 bands in terms of the number of payment transactions and expenditures are from Alberta.

Since the passing of the 1951 Indian Act, First Nations have continuously petitioned for more control over their capital moneys.Footnote 17 However, to date, available opt-in legislation, which provides an alternative to Band Moneys, has been difficult to implement. FNOGMMA is federal opt-in legislation that was designed in cooperation with First Nations. It came into force in 2006 to provide an alternative to the Indian Oil and Gas Act and sections 64 and 66 of the Indian Act (i.e., the sections pertaining to the expenditure of Band Moneys). First Nations that opt-in gain control over oil and gas development and/or control of their trust moneys.

Expected outcomes for FNOGMMA are improved economic development, greater utilization and increased value of community land and resources, increased First Nation authority and control over lands and resources and increased flexibility to react to economic opportunities and community needs. However, to date no First Nation has been successful in the process.

An evaluation of FNOGMMA conducted in 2010 found that the program was too rigorous and difficult for the participating First Nations. Identified barriers and concerns relating to the implementation of FNOGMMA include lack of an enforcement mechanism, loss of federal fiduciary responsibilities, environmental liability, the complexity of oil and gas regime and lack of community capacity. Furthermore, the current FNOGMMA budget does not allocate enough dedicated financial resources to the moneys management component of the program.

First Nations can also gain access to Band Moneys through the settlement of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements (CLCAs), which are modern-day treaties that give Aboriginal signatory groups access to the land and resources. However, CLCAs are complex agreements that redefine a First Nation's relationship with the Crown and the negotiation of CLCAs is costly and time consuming.Footnote 18,Footnote 19

The only way First Nations have been successful in gaining full access to capital moneys has been though court-ordered transfers. Two Alberta First Nations, Samson and Ermineskin, obtained transfers of all present and future capital moneys through terms and conditions set out in a court order. The decision to transfer capital moneys from the Government of Canada to these First Nations was made at their request. Each sought a separate federal court order that prescribed the criteria they were required to meet before the Minister would allow for the transfer of funds. Samson had $350 million transferred outside the CRF in 2006 and Ermineskin received $240 million in 2011. Today, funds generated from reserve lands for Samson and Ermineskin are collected by the Department, but then are transferred to a trust set up by the bands. While litigation has resulted in a positive outcome for these two First Nations, legal settlements are costly, time consuming and do not represent a desirable alternative to Band Moneys.

In short, current alternatives to access Band Moneys are difficult to implement, too costly, or involve lengthy processes. As long as First Nations have no other workable options for accessing Band Moneys held in trust by the Government of Canada, the Band Moneys program continues to be relevant.

Finding # 2: Band Moneys is rooted in legislation and court decisions as a result, the program has not adapted well to emerging federal and departmental priorities.

There are a number of pieces of legislation, which outline the role of the federal government and the Minister of AANDC in relation to Band Moneys. The Canadian Constitution Act, 1867 defines the division of power in Canada and establishes federal government jurisdiction over First Nations people living on and off reserve. Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act prescribes that the Minister has exclusive authority over Indians and lands reserved for Indians. As a result, all title to reserve lands rests with the Crown and all moneys derived from reserve land activities are payable to the Crown. The Financial Administration Act requires these moneys to be deposited into the CRF and directs the record keeping of all moneys, including those deemed Band Moneys.

The Indian Oil and Gas Act defines the management of moneys generated from oil and gas. Moneys are collected by Indian Oil and Gas Canada on behalf of First Nations and deposited into either capital accounts (royalty and bonus) or revenue accounts (rents and access fees) in the CRF. These moneys are accessed like other Band Moneys, pursuant to the provisions of the Indian Act.

The program design and delivery has also been shaped over time by court cases and legal advice and opinions. The results of legal decisions have been incorporated into policies and procedures to reduce the incidence of future litigation and risks associated with the Minister's exercise of discretion over the administration of Band Moneys. The close linkage between Band Moneys, legislation and legal decisions has resulted in an administration design focussed on ensuring compliance with the Indian Act. As a result, the evolving needs of First Nations cannot be easily integrated into program design. Ties to the Indian Act also limits adaptation of Band Moneys to reflect changes in the federal vision and priorities relating to First Nations. This is discussed further below.

At the Crown-First Nations Gathering in January 2012, the Prime Minister highlighted the following federal priorities: 1) improved governance; 2) increased Aboriginal participation in the economy; 3) empowerment of individuals; and 4) sustainable communities. These priorities complement the June 2011 Joint Action Plan between the Minister of AANDC and the Chief of the Assembly of First Nations in which joint commitments were agreed to in the following four areas: 1) Education; 2) Accountability, transparency, capacity and good governance; 3) Economic development; and 4) Negotiation and Implementation. The current operation of the Band Moneys regime needs to better support federal priorities relating to governance, economic development and sustainable communities.

The Government of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations have indicated their support and interest in improving governance through increased transparency. Bill C-27 entitled An Act to enhance the financial accountability and transparency of First Nations, which was introduced in November 2011, demonstrates the federal government's commitment towards this issue. The Actrequires the preparation and public disclosure of audited consolidated financial statements and compensation provided to Chief and Council.

Although the annual Band Moneys reporting process is in line with the Year End Reporting Handbook and Indian Moneys Regulations, findings detailed under the performance section for Band Moneys reveal some weaknesses in reporting on results back to band members. Reporting is provided to AANDC and is focused on expenditures, not impacts on community members and therefore does not permit an analysis of the impact of Band Moneys expenditures on community well-being.

There is no requirement to make reporting on Band Moneys expenditures available to band members – it is left to the band to decide. For bands that are open and transparent, members have access to Band Moneys expenditure information. Interviews revealed that some bands are very open and consult with community members before budget meetings and after the funds are spent. Members of less open bands would not be able to easily access information. If members want access to audited financial statements, they must contact the band and if that is unsuccessful, members can make a request to AANDC. The inconsistencies and difficulties accessing information about Band Moneys expenditures are inconsistent with calls for greater transparency and accountability.

Economic development is a clear priority for both the federal government and First Nations. The 2009 Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and the 2012 Budget emphasized the need for "expanding opportunities for Aboriginal peoples to fully participate in the economy". The discussion guide for the New Federal Framework identified a number of barriers to economic development, including inability to access capital, legislative and regulatory barriers and limited access to lands and resources. Band Moneys impacts all these issues. Capital and revenue moneys represent a source of funds that could be used for economic development. Given the importance of economic development to the future of First Nations, Band Moneys could permit quicker access to funds to allow for a more timely response to emerging opportunities.

While quick access the Band Moneys has been achieved for revenue expenditures, which account for approximately 30 percent of total expenditures, the remaining 70 percent of capital expenditures fall under Section 64 of the Indian Act, which have stricter controls. For Section 69 Bands that have control over the management and expenditure of revenue moneys, funds can be accessed relatively quickly as AANDC provides an approval process with the regional offices, which have authority to approve revenue expenditures. Turn-around times for revenue expenditures for bands without Section 69 authority are also generally processed within established timeframes making revenue moneys readily available for economic development purposes.

However, under the Indian Act, more restrictions are placed on expenditures of capital moneys. The expenditures permitted with capital moneys outlined in sections 64(1)(a)-(j) do not relate specifically to economic development but are more administrative in nature to support a band's day-to-day governance and operations. To use Band Moneys for economic development purposes, bands must use Section 64(1)(k), which requires ministerial approval and involves a lengthy assessment and approval process. Any delays or impediments to accessing capital moneys may translate into missed economic development opportunities and as such, the current process does not align with the priorities of both the federal government and First Nations.

The current design of the Band Moneys program appears to be contrary to the departmental objective of facilitating greater self-sufficiency for First Nations. The concept of self-sufficiency is captured in the departmental vision as follows:

"Our vision is a future in which First Nations, Inuit, Métis and northern communities are healthy, safe, self-sufficient and prosperous – a Canada where people make their own decisions, manage their own affairs and make strong contributions to the country as a whole."

The current Moneys Management Framework under the Department's Program Activity Architecture provides AANDC a control framework over expenditures, which appears to be at odds with this vision.

The lack of alignment with the needs of First Nations and the lack of adaptability to changing priorities suggest that perhaps Indian Moneys should be moved out of the Indian Act. As a result, alternatives should be explored and these alternatives should address the shortcomings of the existing program.

Recommendation # 1:

- Explore the development of a workable alternative to Band Moneys that would provide First Nations access to funds in the Consolidated Revenue Funds outside the constraints of the Indian Act and present proposed alternative to the Strategic Policy Committee.

Recommendation # 2:

- Any changes to Band Moneys and alternatives be designed to increase the transparency of Band Moneys expenditures to members, better support access to capital for economic development and promote greater self-sufficiency.

3.3. Findings – Performance

The evaluation identified two outcomes. The first outcome was that Band Moneys expenditures are made according to the Indian Act and the second outcome was that approved expenditures benefit current and future members (by promoting due diligence in expenditure decisions and preserving capital for future generations).

According to the findings, the first outcome, although focused internally on fulfilling departmental responsibilities in the Indian Act, has been achieved. In reference to the second outcome, while it appears that some processes and requirements for accessing Band Moneys do promote evidence-based decision making, thereby contributing to good-governance, the impact of expenditures on members cannot be determined through existing reporting. In addition, the preservation of capital may not be occurring at a level that will yield sufficient benefit for future generations.

Findings suggest that efficiency and economy could be improved through training and increased communication. However, the most significant impact could come from the implementation of a viable alternative to Band Moneys. Two possible alternatives are outlined in Section 3.3.3 along with suggestions regarding the essential features of a private trust, which could replace Band Moneys in both alternatives.

3.3.1 Effectiveness

Finding # 3: Band Moneys capital and revenue expenditures are approved according to the provisions prescribed under the Indian Act and information requirements aids decision making of First Nations.

The immediate outcome that Band Moneys expenditures are approved according to provisions in the Indian Act has been achieved. AANDC staff interviewed were unanimous in the assertion that the primary purpose of Band Moneys was to execute ministerial responsibilities related to Band Moneys as outlined in the Indian Act. The Manual for the Administration of Band Moneys, which outlines processes and procedures, is updated regularly and half of the IMETA staff interviewed indicated they follow the guide closely.

The 2010 Audit of Trust Accounts found that "controls were in place designed to ensure accurate and timely processing of trust account receipts and disbursements in accordance with all acts and departmental guidelines".Footnote 20 The Individual Affairs Branch has addressed all recommendations from this audit in the Management Response and Action Plan. The Audit resulted in modifications to the TFMS to prompt Band Moneys Officers to insert information before being permitted to proceed to the next screen. This is expected to ensure that expenditure data needed for decision making is tracked appropriately.

Interviews and the document review confirm that the departmental assessment of BCRs promotes due diligence in decision making and contributes to good governance. IMETA staff conduct an assessment of the financial, socio-economic, environmental and legal considerations for each BCR; they review account balances to help preserve the capital balance for future generations; they ensure proposed expenditures comply with expenditures deemed beneficial under the Indian Act; and they require reporting back on expenditures to the Department.

The information requirements are reasonable and provide useful information to bands for expenditure decisions. However, the extent to which they contribute to a permanent impact on good governance or the promotion of an understanding of the importance of checks and balances is unknown. Finally, despite the success in achieving this immediate outcome, it is important to note that this outcome is focused more on the needs of the Department (i.e., fulfillment of the Indian Act) than the needs of bands and their membership. A Performance Measurement Strategy would contribute to the identification and articulation of outcomes that are externally focused on the needs of First Nations.

Finding # 4: There has been a positive growth in capital and revenue balances over time.

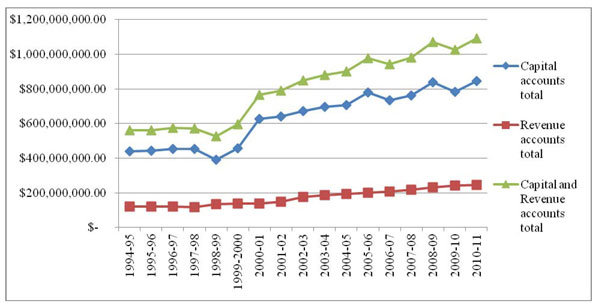

Band Moneys has been successful in preserving some capital moneys for the use of future generations. This is reflected in Figure 3.3 below, which shows positive growth in both capital and revenue balances between 1994-95 and 2010-11.

Figure 3.3 Total amounts in Band Moneys capital accounts, revenue accounts and both accounts together between 1994-95 and 2010-11.Footnote 21

Text alternative for Figure 3.3 Total amounts in Band Moneys capital accounts, revenue accounts and both accounts together between 1994-95 and 2010-11

The Band Moneys figure denotes three data lines, with data points occurring annually for the time period range of 1994-5 to 2010-11, against a financial capital range of $0 to $1.2 billion, increasing by increments of $200 000 000. The three data lines represent balances for each of the following: "capital accounts total"; "revenue accounts total"; and "capital and revenue accounts total".

Each of the data lines is upward sloping over the time range. The "revenue accounts total" line begins below $200 000 000 in 1994-5 and increases to slightly above $200 000 000 by 2010-11. The "capital accounts total" line increases from slightly above $400 000 000 in 1994-5 to slightly above $800 000 000 in 2010-11, with slight line dips in 1998-99, 2006-07 and 2009-10. The "capital and revenue accounts total" line begins slightly below $600 000 000 in 1994-95 and ends above $1 000 000 000 by 2010-11, with a slight dip in 1998-99, an increase by almost $200 000 000 in 2000-01 and slight dips in 2006-07 and 2009-10.

While capital accounts are growing, Figure 3.4 below shows that most capital moneys are being spent. Between 1994-95 and 2010-11, capital payments amounted to an average of 85 percent of capital receipts.Footnote 22 For the duration of the evaluation from 2006-07 to 2010-11, payments accounted for an average of 93 percent of capital revenues.

Figure 3.4 Total receipts and payment amounts in Band Moneys capital accounts between 1994-95 and 2010-11, as well as the average for the time period. Footnote 23

Text alternative for Figure 3.4 Total receipts and payment amounts in Band Moneys capital accounts between 1994-95 and 2010-11, as well as the average for the time period