Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program

Final Report

Date : April 2013

Project Number: 1570-7/11008

PDF Version (346 Kb, 67 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Findings – Relevance

- 4. Findings – Performance/Effectiveness

- 5. Findings – Efficiency/Economy

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix B: Social Development Programs Logic Model

List of AcronymsFootnote 1

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| CFS |

Child and Family Services |

| EPFA |

Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| FGC |

Family Group Conferencing |

| FNCFS |

First Nations Child and Family Services |

| IM/IT |

Information Management/Information Technology |

| IMS |

Information Management System |

| MFCS |

Mi'kmaq Family and Children's Services |

| NOM |

National Child Welfare Outcomes Matrix |

Executive Summary

This Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia is part of a multi-year Strategic Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach (EPFA) for the First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) Program, which began with an implementation evaluation in Alberta in 2009-10. The purpose of the strategic evaluation is to look at jurisdictions individually two-three years after the approach has been implemented to examine issues of relevance, performance, efficiency and effectiveness. In 2010-11, a Mid-Term National Review was conducted to consider the relevance of the EPFA from a national perspective, provide insight on discussions held to establish tripartite frameworks, as well as to consolidate promising practices in prevention programming nationally and internationally to raise awareness of innovative and effective practices that may support First Nation agencies in serving their communities. To the extent possible, this evaluation elaborates on findings from the Mid-Term National Review.

The FNCFS Program funds FNCFS agencies to provide culturally appropriate child and family services in their communities, so that the services provided to First Nations children and their families on reserve are reasonably comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar circumstances and geographic location within Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) program authorities. FNCFS agencies receive their mandate and authorities from provincial/territorial governments and function in a manner consistent with provincial or territorial child and family services legislation. In areas where FNCFS agencies do not exist on reserve, AANDC funds those services provided by provincial organizations or departments.

Starting in 2007, AANDC began reforming the FNCFS program from a protection to a prevention focused approach on a jurisdiction by jurisdiction basis, beginning in Alberta.Footnote 2 Prevention services may include, but are not limited to, respite care, after-school programs, parent/teen counselling, mediation, in-home supports, mentoring and family education. AANDC, provincial and First Nations representatives must enter into a Tripartite Accountability Framework in order to move to an enhanced prevention model. The framework can vary from region to region but is based on reasonably comparable funding amounts provided to agencies by provincial governments in communities in similar geographic areas and circumstances.

In Saskatchewan, there are 17 FNCFS agencies that provide mandated child and family services to 67 of the 70 First Nations communities in the province, while the remaining three communities are served by the province. In Nova Scotia, the Mi'kmaw Family and Children's Services (MFCS) provides services to all 13 Mi'kmaw communities in that province.

Some of the limitations of this report include a lack of agency directors in Saskatchewan willing to be interviewed for the study, and a low response rate for a web-based survey aimed at agency staff and community members. Consequently, the survey results were not included in the findings of this report. Moreover, while two case studies were conducted as part of this evaluation, only one received the community support needed to be included in the findings. The evaluation supports the following conclusions regarding relevance, performance/ effectiveness and efficiency/economy based on the analysis and triangulation of four lines of evidence: document review, literature review, key informant interviews and a case study.

Relevance

This section focused primarily on the identified prevention and capacity needs of FNCFS agencies in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, given that a national review covered the relevance of the EPFA in 2010-11.

The main child welfare issues in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia stem from an over-representation of First Nations children in care, a rise in complex medical needs and high cost institutional care, and a rise in older children coming into care. Furthermore, poverty, housing, substance abuse, mental health, child abuse and neglect, poor parenting skills and a lack of alternative care options were cited as the most common parental and community issues facing First Nations communities in these jurisdictions.

Training and capital infrastructure are the primary capacity needs identified by agencies. Agencies are largely supported in their work through federal and provincial government resources, and in Saskatchewan by the First Nation Child and Family Institute. The evaluation found that proper supports are in place to allow agencies to deliver services in a way that is culturally appropriate to their communities.

Performance/Effectiveness

Design and Delivery: In terms of financial effectiveness, it is unclear whether the EPFA is flexible enough to accommodate provincial funding changes throughout the 5-year funding cycle. There is also a risk that if maintenance costs exceed the agencies' allocation, this could affect agencies in their ability to provide consistent programming.

In terms of human resources, AANDC Headquarters has recently staffed its vacant positions. Both the Saskatchewan and Atlantic regional offices struggle to effectively perform their work given their current staffing limitations. Agencies in Saskatchewan report a continuing struggle with staffing shortages, and MFCS has experienced caseload ratios that exceed the provincial standard, though these numbers have fluctuated from year to year. Most agencies report that it is difficult to recruit and retain qualified staff, particularly First Nation staff.

The evaluation found evidence to support an increase in communication between AANDC Headquarters and the regions, the Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia provincial governments and agencies.

Overall, some of the most common challenges identified in the implementation of the EPFA are unrealistic expectations of what FNCFS agencies can carry out, particularly by community leadership, as well as difficulties based on large geographical distances/travel.

Monitoring and Reporting: Although a significant number of reports are currently required from agencies, outcomes are generally not reported at the departmental level. The Information Management System (IMS) is expected to support more robust data collection, though the Department has noted certain risks, including the timeliness and implementation of the system, a lack of operational protocols, as well as challenges in human resources, financing and change management. Areas for improvement include the improvement of data sharing, streamlining of reporting and providing better feedback to agencies on their performance.

Impacts: MFCS in Nova Scotia is supported legislatively in providing prevention services but this is not the case in Saskatchewan. Most agencies report that awareness of prevention programming has increased in their communities and that it will take time to change community perspectives. Overall, there has been an increase in access to prevention services. The EPFA is largely considered to support the security and well-being of children and families through a variety of measures, including an increase in prevention activities.

Economy/Efficiency

Economy and efficiency was found through the extensive use of inter-agency and community-level partnerships. AANDC has spent a significant amount of money on Information Management/Information Technology (IM/IT) systems at both the federal and agency level, though there remains great potential for continued economic and data inefficiencies, duplication of information and continued reporting burden for agencies. The evaluation found that FNCFS agencies have invested in capital expenditures to meet an increasing variety of needs, and concludes that AANDC could improve the efficiency of the EPFA by better coordinating various federal programming that affect children and parents requiring child and family services.

Based on these findings, it is recommended that AANDC:

- Ensure that there are regular reviews of the costing models to ensure agencies are able to meet changing provincial standards and salary rates while maintaining a high level of prevention programming to meet community needs;

- Work collaboratively with MFCS and the Province of Nova Scotia to ensure that the agency is providing adequate services to all communities as per provincial legislation and standards;

- Ensure AANDC regional offices have adequate capacity to effectively carry out their current job functions, as well as the successful and ongoing monitoring of the IMS;

- Work with the provinces, agencies and appropriate First Nation organizations to develop and implement a coordinated approach to information management, in order to improve efficiency, reduce the reporting burden for agencies and allow AANDC to fully report on outcomes; and

- Work with other AANDC programming and federal partners (including Health Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, the Department of Justice and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada) to facilitate the coordination of services affecting children and parents requiring child and family services.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program

Project #: 1570-7/11008

The First Nations Child and Family Services Program agrees with the recommendations produced in this Implementation Evaluation. However, it is important to provide some context to clarify the degree to which AANDC will be able to implement some of the recommendations. This is especially important with respect to Recommendations 1, 3 and 5. Recommendation 1 is to "Ensure that there are regular reviews of the costing models to ensure agencies are able to meet changing provincial standards and salary rates while maintaining a high level of prevention programming to meet community needs. Recommendation 3 outlines the need to "Ensure AANDC regional offices have adequate capacity to effectively carry out their current job functions, including the successful and ongoing monitoring of the Information Management System (IMS)". AANDC can review costing models under EPFA as per Recommendation 1, but any changes to costing models that result in increased funding will create cost pressures on the program that may not be able to be addressed without seeking external funding sources (reallocations within AANDC or new funding). In the same vein, although there are actions that can be taken by AANDC to increase capacity in regional offices to perform these tasks, efforts in this area will be limited by the current overall environment of workforce adjustment and reduced spending. For Recommendation 5, which is to "Work with other AANDC programming and federal partners, as appropriate, to facilitate the coordination of services affecting children and parents requiring child and family services", similar limitations apply, as workforce adjustment and reduced spending impacts the availability and capacity of human resources in multiple departments to pursue horizontal work. Another limitation to AANDC's ability to effectively implement this recommendation is the limited scope of control it has over other government departments and other levels of government, which would all have to agree and commit to working together on this "whole-of-government" issue.

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ensure that there are regular reviews of the costing models to ensure agencies are able to meet changing provincial standards and salary rates while maintaining a high level of prevention programming to meet community needs; | We do concur. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: Fall 2012 |

| AANDC will participate in tripartite meetings with provinces and agencies on EPFA implementation, which will include the review of costing associated with EPFA. AANDC Headquarters will also continue to liaise with Regions through monthly conference calls and regular meetings to review financial pressures that may arise during EPFA implementation. These meetings and discussions will allow Headquarters to determine whether pressures can be addressed and forecast future costing, while also allowing Headquarters and regions to develop possible mitigation strategies for arising issues. | Completion: Ongoing |

||

| 2. Work collaboratively with MFCS and the Province of Nova Scotia to ensure that the agency is providing adequate services to all communities as per provincial legislation and standards; | We do concur. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: |

AANDC will intensify its collaborative work with the Department of Community Services and MFCS to achieve a thorough understanding of agency resources and expenditures; to develop a sustainable plan for effective agency operations and service delivery; and to support a delivery mechanism that serves on reserve First Nation populations within provincial standards and within current allocations. AANDC has provided funds to MFCS to address Maintenance and Operational shortfalls since fiscal year 2010-2011. Since the fall of 2011, the tripartite Working Group in Nova Scotia has met regularly to discuss the Agency's staffing structure and to develop draft Terms of Reference for a consultant to assist the Agency in developing an updated Business Plan/service delivery model. AANDC has regular bilateral calls with the province, and the tripartite Executive Steering Committee held meetings in February, September, November of 2012 and January 2013, to discuss the Working Group results, and to develop an appropriate plan of action. |

Completion: |

||

| 3. Ensure AANDC regional offices have adequate capacity to effectively carry out their current job functions, including the successful and ongoing monitoring of the Information Management System; and | We do concur. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: |

AANDC will update the National Social Programs Manual and will produce technical interpretation bulletins and information circulars, as required, in order to clarify program requirements, enhance compliance and reduce reporting burden in the regions. These documents will ensure that proper processes are followed which will eliminate unnecessary steps in reporting and program management, serving to alleviate the administrative burden on regional staff. Through the implementation of the Social Policy and Programs Branch's Management Control Framework, the Branch will continue to streamline the reporting process, in particular Social Policy and Programs Branch's Data Collection Instruments, in support of creating efficiencies and effectiveness in the implementation of the IMS. AANDC Headquarters and regions will continue to support one another through regular teleconferences and face-to-face meetings/ videoconferences to identify these efficiencies in order to help ease the workload burden that has been identified and to ensure that operation support tools and mechanisms are in place come time for the IMS implementation. The FNCFS IMS Team is in the process of developing an Organizational Change Management Framework that will support on an ongoing basis the transition to the FNCFS IMS. This framework includes: an organizational readiness assessment; a transition plan that reflects all necessary activities to ensure that regional offices and Headquarters staff are ready for the implementation and use of the system; Headquarters to regions communications plan (for both pre and post-production of the system), and; a training strategy which includes the different training methods to address the needs of all the users, and actual delivery of training. Once implemented, there will be post-implementation on-going support from both Headquarters FNCFS program staff and the Information Management Branch. Training for regions on the first phase of the IMS began January 28, 2013, and will continue during the week of March 11-14, 2013. In early 2013, additional on-site regional training sessions are planned to help ensure that regional staff clearly understand how to utilize the new system. |

Completion: |

||

| 4. Work with the provinces, agencies and appropriate First Nation organizations to come up with and implement a coordinated approach to information management, so as to improve efficiency, reduce the reporting burden for agencies and allow AANDC to fully report on outcomes. | We do concur. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: |

| Implementing the recommendation is a multi-year process that involves rationalizing the reporting data that AANDC seeks from First Nations and other sources for program management and performance measurement purposes. | Completion: March 2013 |

||

First point made by EPMRC: "While the agency and provincial IM system may be linked, the recommendation speaks to collaboration between all three parties to reduce duplicative reporting – enhance the first point to address this issue." Second point made by EPMRC is to re-word the second point (of an earlier version) to reflect that: "AANDC is currently undertaking discussions…" This point is moot because the sentence in question has been re-worded entirely. |

AANDC is currently involved in many collaborative initiatives to streamline processes pursuant to the Modernizing Grants and Contributions Initiative. Social Policy and Programs Branch remains engaged with AANDC regions to support regional innovation. For example, many regions are working with First Nations to support performance measurement that is meaningful at the community level. Social Policy and Programs Branch will access this data and ensure that information is collected only once. Social Policy and Programs Branch also remains engaged with provincial and territorial innovation, with the intent to share knowledge (like reciprocal indicators and data source sharing), streamline and access performance information where possible. AANDChas an evergreen multi-step plan that includes:

|

||

| Third point made by EPMRC is that "Under the multi-step plan for DCIs, clarification is required for what is meant by "collect authoritative data only that will inform results?"" | Data Collection Instrument management (ongoing):

|

||

| 5. Work with other AANDC programming and federal partners, as appropriate, to facilitate the coordination of services affecting children and parents requiring child and family services. | We do concur. | Director General, Social Policy and Programs Branch | Start Date: |

| AANDC will continue to work collaboratively with relevant internal and other federal partners, as well as provincial ministries through existing tripartite tables, bi-lateral forums and other communication opportunities. As an example, AANDC will continue to participate in discussions with Health Canada in order to further align programming available to First Nations children and families. AANDC will continue to collaborate with its internal partners on related programs such as Family Violence Prevention Program and Education. AANDC has participated in two meetings of the FPT Working Group of the Directors of Child Welfare, with the most recent being in October 2012, in order to identify ways in which AANDC can work collaboratively with other partners moving forward, and will continue to engage this group on FNCFS matters. | Completion: |

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed by:

Françoise Ducros

Assistant Deputy Minister, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on April 25, 2013.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This Implementation Evaluation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia is part of a multi-year Strategic Evaluation of the Implementation of the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach (EPFA) for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program, which began with an implementation evaluation in Alberta in 2009-10. The purpose of the strategic evaluation is to look at jurisdictions individually two-three years after the approach has been implemented to address issues of relevance, and to the extent possible, performance, efficiency and effectiveness. In 2010-11, a Mid-Term National Review was undertaken to consider the overall relevance of the EPFA, promising practices in prevention programming, as well as to provide some insight on discussions to establish tripartite frameworks to date. Following the current evaluation, implementation evaluations are scheduled for Prince Edward Island and Quebec in 2012-13 and for Manitoba in 2013-14. Further evaluative work will be considered as agreements are reached in remaining jurisdictions.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

The First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) Program funds FNCFS agencies to provide culturally appropriate child and family services in their communities, so that services provided to First Nations children and their families on reserve are reasonably comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar circumstances within program authorities. To this end, the program funds and promotes the development and expansion of child and family services agencies designed, managed and controlled by First Nations. Since child and family services is an area of provincial jurisdiction, these First Nation agencies receive their mandate and authorities from provincial or territorial governments and function in a manner consistent with existing provincial or territorial child and family services legislation.

Government funding for child welfare is complex, and involves hundreds of bilateral and trilateral agreements. The program currently funds 105 First Nation agencies. In areas where First Nations Child and Family Services agencies do not exist, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) funds services provided to on-reserve recipients by provincial or territorial organizations or departments.

In 2007, the FNCFS Program began its reform to the EPFA from the previous funding model for all jurisdictions except Ontario and AlbertaFootnote 3 known as Directive 20-1. Directive 20-1 has been in place since April 1, 1991, and strictly funds according to a formula for operations (including limited prevention services) and reimburses for eligible maintenance expenditures, based on actual costs.

The EPFA reorganized the FNCFS Program's funding structure to include three targeted streams of investment – maintenance, operations, and prevention/least disruptive measures – that are only eligible for use for Child and Family Service (CFS) activities, though FNCFS agencies have the ability to move money between the three streams to better meet their needs.

The EPFA represents a refocusing of FNCFS funding towards a more prevention-based approach. Prevention services may include, but are not restricted to, respite care, after-school programs, parent/teen counselling, mediation, in-home supports, mentoring, and family education. Prevention services may also assist in the earlier and safe return of a child to their family. The rationale for this shift is that the implementation of prevention services in the early stages of a child's life often mitigates the need to bring children into care, and thereby supports keeping First Nation families together. This is consistent with provinces that have largely refocused their own CFS services/system from protection to prevention services.

The EPFA supports:

- Families getting the support and services they need before they reach a crisis;

- Community-based services and the child and family system working together so families receive more appropriate services in a timely manner;

- First Nations children in care benefitting from permanent homes (placements) sooner by, for example, involving families in planning alternative care options;

- Services and supports co-ordinated in the way that best helps the family; and

- Coordination of services – funding for staff/purchase services.

To date, six jurisdictions covering 68 percent of all First Nation children ordinarily living on reserve are currently under the EPFA modelFootnote 4 and it is expected that the remaining jurisdictionsFootnote 5 will move to the EPFA by 2014-15.

AANDC's FNCFS programming is funded through the following authority: Payments to support Indians, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in social development (support culturally appropriate prevention and protection services for Indian children and families resident on reserve), and is derived from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-6, s.4 and subsequent policy proposals.Footnote 6 Under AANDC's Program Alignment Architecture, the program falls under the Strategic Outcome "The People,' which aims to promote "Individual and family well-being for First Nations and Inuit."

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

AANDC funds a suite of social programming, including the First Nations Child and Family Services Program, the Family Violence Prevention Program, the Income Assistance Program, the National Child Benefit Reinvestment Program and the Assisted Living Program. The overall objective of AANDC's social programs is to "provide funding to First Nations administrators to provide on-reserve residents with individual and family supports and services that have been developed and implemented in collaboration with partners in order to contribute to:

- fostering greater self-sufficiency for First Nation individuals and communities;

- improving the quality of life on reserve;

- creating a community environment where incidences of family violence and child abuse are reduced or eliminated; and

- supporting greater participation in the labour market and fully sharing in Canada's economic opportunities."Footnote 7

More specifically, the objective of the FNCFS Program is to ensure the safety and well-being of First Nations children on reserve by supporting culturally appropriate prevention and protection services for First Nations children and families, in accordance with the legislation and standards of the province or territory of residence. In addition, the incremental investments of the EPFA are expected to allow agencies to deliver child and family services in accordance with provincial legislation, including enhanced prevention services.

According to the original program documentation, the immediate outcome expected from EPFA investments was increased access to services that protect children and families at risk at a standard reasonably comparable to non-First Nations communities in similar circumstances. Social workers are expected to be able to strengthen partnerships through horizontal integration with other community services/organizations for better case management (i.e. through case conferencing) to improve service delivery and provide integrated responses to meet the real needs of First Nation children and families. Capacity development support would be provided to smaller agencies that may lack the economies of scale to deliver the full continuum of services.

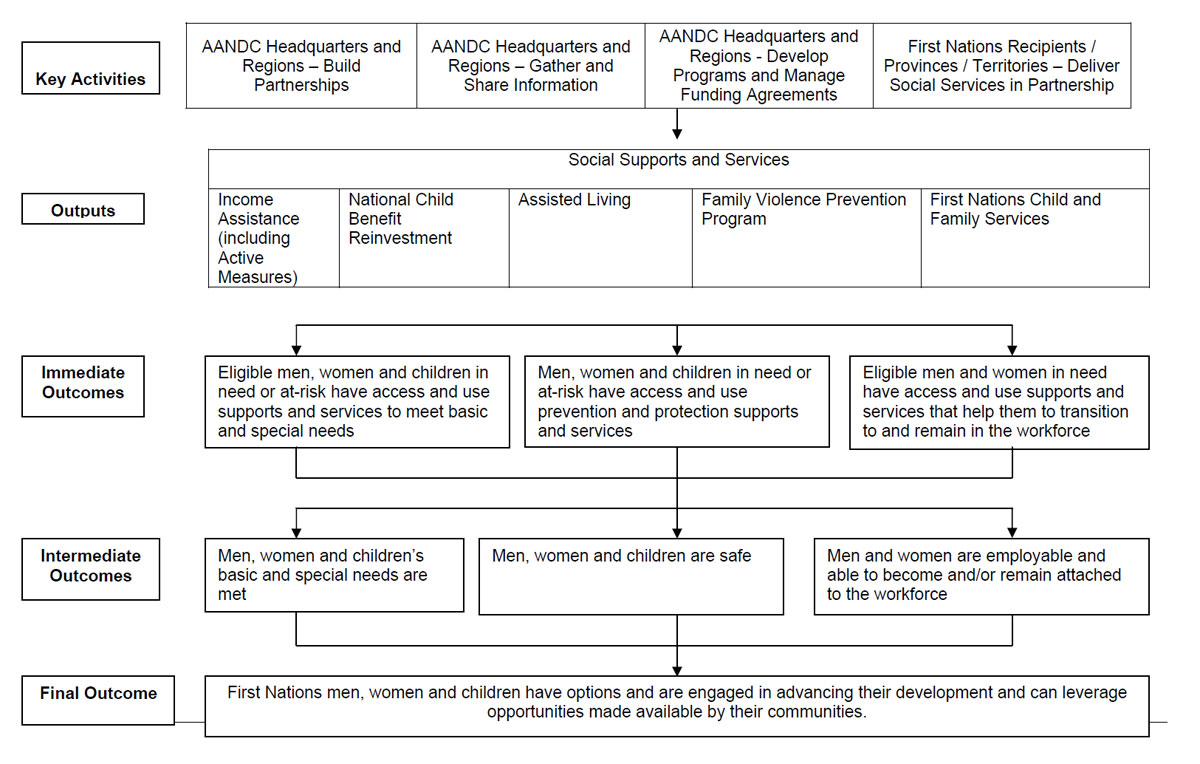

Currently, program outcomes are captured in the Social Development Programs' performance measurement strategy. The relevant immediate outcome for the FNCFS program is that "men, women and children in need or at-risk have access and use prevention and protection supports and services." Key indicators for this outcome include: percentage of First Nations men, women and children in need or at-risk, ordinarily resident on reserve, that are using prevention and protection supports and services and rates of ethno-cultural placement matching. The first indicator is meant to determine the extent to which prevention and protection supports and services either on or off reserve, or on another reserve, are available to First Nations ordinarily resident on reserve, and the latter adopts the National Child Welfare Outcomes Indicator Matrix (NOM), which states: "Given that placement matching for Aboriginal children is legislated in most jurisdictions, the priority NOM measure tracks the proportion of placed Aboriginal children in homes with at least one of the caregivers is Aboriginal."Footnote 8

Intermediate outcomes according to original program documentation were expected to include a more secure family environment, reduced need for the removal of children from parental homes, reduced incidents of abuse, and overall improvement in child well-being. To measure attainment of this goal, more quantifiable outcome data was to be gathered. At the planning phase of this approach, AANDC committed to partner with provinces and First Nations to ensure that First Nations' indicators can be extracted directly from the provincial database.

In the performance measurement strategy, this intermediate outcome translates to "Men, women and children are safe." Performance measures for this outcome include mortality rates, injury rates and recidivism rates. The mortality rates indicator is reflective of the NOM indicator "percentage of children who die while in the care of child welfare services," and is meant to assess the overall conditions of safety. The purpose of measuring injury rates is to assess overall safety in the communities and is reflective of the NOM indicator "serious injury and death." Finally, recidivism rates are expected to reflect the long term effectiveness of services, and is also reflective of NOM.

The expected ultimate outcome for the FNCFS Program is to have a more secure and stable family environment for First Nation children ordinarily resident on reserve.

The logic model for the Social Development Programs' Performance Measurement Strategy can be found in Appendix B.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

AANDC Headquarters establishes on a national basis the program guidelines, the terms and conditions that must be included in each funding arrangement, as well as the policy related to monitoring and compliance activities. The specific role of Headquarters is to:

- Provide, through the regions, funding for recipients to provide services to children and families as authorized by the approved policy and program authorities;

- Lead in the development of FNCFS policy;

- Consider proposals for change coming from regional representatives and First Nations practitioners;

- Provide oversight on program issues related to the FNCFS policy as well as to assist regions and First Nations in finding solutions to problems arising in the regions;

- Provide leadership in collecting data and ensuring that reporting takes place in a timely manner;

- Interpret FNCFS policy and assist regions in providing policy clarification to recipients, provinces and territories; and

- Provide amendments to the National Program Manual as required and to ensure that program policy documentation is consistent with approved policy and program authorities.

With the support of regional staff, the Regional Director General in each region is responsible for implementing and administering the social development programs in accordance with the guidelines issued by the program managers at Headquarters. This includes, for example:

- assessing the eligibility of recipient applications;

- entering into financial arrangements with approved recipients in accordance with the transfer payment Terms and Conditions; and

- monitoring, collecting and assessing both the financial and program performance results of individual recipients, and taking appropriate remedial action as appropriate.

FNCFS falls within provincial/territorial jurisdiction. It is the role of the province or territory to:

- Mandate recipients in accordance with provincial or territorial legislation and standards;

- Regulate recipients in their activities as they relate to the legislation and standards;

- Provide ongoing oversight to recipients and to take action if the requirements are not being met;

- Participate in tripartite activities such as negotiations, dispute resolution and consultations as well as regional tables;

- Apply the legislation and standards for all child and family services equally to all residents of the province or territory on and off reserve;

- Provide information on outcome data to the federal government; and

- Adhere to other roles and responsibilities as determined through agreements, such as the Tripartite Accountability Framework.

FNCFS agencies are responsible for delivering the FNCFS Program in accordance with provincial legislation and standards while adhering to the terms and conditions of their funding agreement. FNCFS service providers include, but are not limited to, First Nations (as represented by Chiefs and Councils); and their organizations such as tribal councils or agencies (such as CFS agencies in various communities).

Eligible recipients for FNCFS funding are:

- Councils of Indian bands recognized by the Minister of AANDC;

- Tribal councils;

- FNCFS agencies or societies duly mandated by the relevant province/territory;

- Provincial/territorial government;

- Other mandated CFS providers, including provincially mandated agencies/societies; and

- First Nations and First Nations organizations who apply to deliver capacity-building activities, including the development of newly-mandated FNCFS programs.

Beneficiaries of the FNCFS Program include at-risk First Nations children and their families on reserve that require access to prevention/least disruptive measures services and/or child protection services, including child placement out of the parental home.

1.2.4 Program Resources

The total estimated funding level for the FNCFS Program in 2010-11 is $579 million in contributions, including new resources through the EPFA. In Saskatchewan, funding has gone up by approximately 50 percent over the past five years, and in the Atlantic region funding has gone up slightly. Table 1 provides a regional breakdown of FNCFS funding allocations over the past five fiscal years.

| Region | Funding Type | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | A Based | 37,688.2 | 49,782.4 | 52,095.1 | 50,353.6 | 52,543.5 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| AB | A Based | 107,786.9 | 105,437.9 | 105,213.6 | 96,747.1 | 103,313.6 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 15,300.0 | 18,700.0 | 21,700.0 | 21,700.0 | |

| SK | A Based | 54,614.5 | 55,724.6 | 51,838.8 | 56,570.8 | 60,961.2 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19,100.0 | 20,000.0 | 21,000.0 | |

| MB | A Based | 72,818.7 | 78,384.3 | 85,244.5 | 95,566.4 | 85,435.6 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17,600.0 | |

| ON | A Based | 104,087.2 | 102,966.4 | 104,338.2 | 114,351.7 | 116,246.0 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| QC | A Based | 38,283.0 | 45,913.2 | 45,796.7 | 49,291.6 | 49,215.2 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6,100.0 | 11,400.0 | |

| AT | A Based | 25,933.5 | 28,118.5 | 29,953.6 | 27,938.0 | 28,935.5 |

| EPFA** | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1,900.0 | 2,200.0 | 2,300.0 | |

| YK | A Based | 8,283.4 | 8,263.6 | 8,886.9 | 8,819.1 | 8,400.0 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| All Regions | A Based | 449,495.3 | 474,590.9 | 483,367.5 | 499,638.4 | 505,050.5 |

| EPFA | 0.0 | 15,300.0 | 39,700.0 | 50,000.0 | 74,000.0 | |

| Total FNCFS | 449,495.3 | 489,890.9 | 523,067.5 | 549,638.4 | 579,050.5 | |

| **These figures are for Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. A-Based = Existing Funding prior to EPFA EPFA = Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach |

||||||

As a result of moving towards the EPFA, a significant amount of new resources have been invested into the FNCFS Program. More than $100 million annually in additional funding will be dedicated to the implementation of the prevention-based model by 2012-13. In Saskatchewan, an additional $104.8 million dollars was provided for the implementation of the EPFA over five years, with $22.8 million dollars in ongoing annual funding. In Nova Scotia, an additional $10.2 million dollars was provided over five years, with $2.2 million in ongoing annual funding.

Allocation from Headquarters to Regional Offices

For regions under the EPFA, funding models are designed during tripartite meetings between First Nations, AANDC officials and provincial representatives and reflect information provided during those discussions about provincial funding of child welfare. These costing models are particular to each jurisdiction and take into account the respective provincial program salaries and caseload ratios to determine provincial comparability within FNCFS Program authorities. The costing models under this approach include three distinct funding streams:

- Operations – Funding supports administration (i.e. staff salaries, rent, insurance, etc.) and protection casework. The amount of funding provided to a recipient is formula-driven, based on an amount per First Nations child on reserve 0-18 years, plus an amount per band and an amount based on the remoteness where applicable.

- Maintenance – Maintenance is budgeted annually based on actual expenditures of the previous year. Funding is based on needs and reimburses actual (per diem and special needs) non-medical eligible costs for Indian children ordinarily resident on reserve taken into care and placed in an alternate care situation outside of the parental home (i.e. foster home, group homes or institutions). Placements can occur on or off reserve.

- Prevention – Prevention is used to support programs that reduce the need to remove children from the parental home by providing tools that allow individuals to better care for their children, as well as to promote increased permanency planning for eligible children in care. Eligible expenditures may include services designed to keep families together and children in their own homes (i.e. homemaker and parent aid services, mentoring services for children, home management, non-medical counseling services not covered by other funding sources).

Under the EPFA, funding can be moved between streams for the purpose of addressing needs and circumstances facing individual communities.

In each jurisdiction, a costing model is developed based on discussions among First Nations, the province/territory and AANDC. The costing model provides an amount for core operations that does not change with the percentage of children in care to allow for a stable flow of funding to agencies. Maintenance costs, however, are funded based on actual expenditures from the previous year, and are not dependent on an assumed fixed percentage of children in care.

Funding of these agencies is through Flexible Transfer Payments, which enables agencies to direct funds to program areas as required within the authorities of the FNCFS Program. Those funds are only eligible for use for FNCFS, but agencies have the ability to move money between the three streams.

In addition to the EPFA, First Nation organizations/Indian bands may be eligible for funding under the Social Development Program Management Infrastructure Initiative, so long as they have a population catchment of at least 1,400 and meet the following criteria:

- Integrated delivery of multiple social development programs;

- Show interface/linkages with provincial/territorial and/or federal programs; and

- Demonstrate the capacity to perform specified functions.

Eligible costs under this initiative include:

- Salaries, wages and benefits;

- Travel and accommodation;

- Insurance;

- Research, policy development and program modification or adaptation;

- Instructional services, public education and information materials;

- Office supplies and office equipment;

- Telecommunications, printing, professional services, other related office costs;

- Specific costs related to providing capacity development and professional development opportunities for First Nations Child and Family Service agencies to deliver a full range of provincially comparable services;

- Conduct of workshops on governance, conflict of interest, training of culturally specific child care and family support workers, Executive Director training, and the documentation and dissemination of best practices in child welfare delivery;

- Provision of policy coordination and analysis, program training, research and development, and agency operational support and assisting in making linkages to holistic and integrated service delivery to enhance agencies abilities to provide effective planning, services and programs for their children, families and communities; and

- Facilitation of discussions on issues of mutual interest among First Nations, AANDC and provinces/territories and playing a role in the development and support of provincially approved First Nations child and family services standards and the development of a compatible FNCFS management information system.

Allocation from Regions to Stakeholders

Under the EPFA, funds are allocated from regions to recipients based on a formula that accounts for operations and prevention services. Child maintenance funding allocations are based on the previous year's actual maintenance expenditures. Operations, maintenance and prevention funding can be found within a recipient's contribution agreements.

1.3 Regional Profiles

1.3.1 Saskatchewan

In Saskatchewan, there are 17 FNCFS agencies that provide mandated child and family services to 67 of the 70 First Nations communities in the province, while the remaining three communities are served by the province. FNCFS agencies thus provide services to over 95 percent of the 0-18 age group on reserve, and receive funding directly from AANDC. Overall, Saskatchewan has approximately 1/5 of the on reserve population in Canada.Footnote 9

Child and Family Services in Saskatchewan are managed by the Ministry of Social Services through a delivery system, which consists of three provincial regions with offices in 22 communities staffed by provincial social workers. The Ministry of Social Services administers these services through the Saskatchewan Child and Family Services Act (Chapter C-7.2 of the Statutes of Saskatchewan, 1989-90) and subsequent legislation and amendments pertaining to delivery of child and family welfare services (e.g., The Adoption Act, 1998). The Child and Family Services Act enables the Minister to enter into delegation agreements for the provisions of children services to First Nations families living on reserves (s 61(6)). The Province of Saskatchewan delegates on reserve child protection services to FNCFS agencies.

In 2008, AANDC announced the establishment of the Tripartite Framework Agreement for the Province of Saskatchewan. AANDC committed an additional $104.8 million over five years to support the implementation of the EPFA in Saskatchewan.

The current provincial system is designed in such a way that only families who meet a "threshold"Footnote 10,Footnote 11 of need are helped by the system. This means that the vast majority of referrals at the provincial level are not served. The Saskatchewan Child Welfare Review Panel in 2010 noted that "we need to get out in front of child protection issues by refocusing the provincial child welfare response around prevention."Footnote 12 As of August 2011, the province had signed two historic Letters of Understanding with First Nation agencies to renew the CFS delivery system and move towards a more risk prevention methodology in delivering CFS.Footnote 13

Moreover, the Saskatchewan First Nations Family and Community Institute was recently established to provide support to the First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan in such areas as research, policy analysis and development, training, and the development of standards.

1.3.2 Nova Scotia

In Nova Scotia, the Department of Community Services manages Child and Family Services for children at risk due to abuse and/or neglect, while all other family support services are provided through the Family and Youth Services division of the department. Service is delivered through provincial district offices and independent agencies including the Mi'kmaw Family and Children Services (MFCS).

The Nova Scotia Children and Family Services Act mandates the function of all child welfare agencies in the province. Sections 36 and 68 of the Children and Family Services Act names the MFCS as the sole service provider for care of First Nation children and families in Nova Scotia, with the singular authority to provide permission for the care of any Aboriginal child to be transferred to any other agency; and to enter into any adoption agreements for Aboriginal child placements. The Act has emphasized the importance of prevention for families at risk since its enactment in 1991. Overall, the Province of Nova Scotia qualifies working with families while children are still in the home as basic child protection services. Prevention services, in their estimation, are the larger community services that work to increase the overall community well-being.

Funding for the MFCS is provided by AANDC for delivering services to the 13 Mi'kmaw bands, while MFCS also receives financial support from the Department of Community Services when dealing with Mi'kmaw children off reserve. MFCS currently has two offices: Eskasoni (Cape Breton) and Indian Brook (near Halifax).

In 2008, AANDC, MFCS and the Province of Nova Scotia reached a Tripartite Framework Agreement, which solidified the move towards the EPFA and includes the following basic principles:

- Culturally appropriate services;

- An alternative response model;

- Effective case management;

- Customary care and adoptions as permanent care solutions for children;

- Partnerships supported by engagement with interagency committees and relevant community resources; and

- A program based on holistic desired outcomes for child, family and community health and well-being.Footnote 14

2. Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The scope of the evaluation includes perspectives from AANDC, the provinces of Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, as well as FNCFS agencies and First Nation community members in these two provinces with regards to relevance, performance/effectiveness and efficiency/economy.

The evaluation examined relevant documents and literature over the past 10 years as well as program activities around the EPFA from 2007 to present. Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in June 2011. Field work was conducted between December 2011 and March 2012.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the Terms of Reference, the review focused on the following key issues:

Relevance

1. What are the identified child welfare and prevention needs of First Nations in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia?

2. What are the program support and capacity needs in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia?

Performance/Effectiveness

3. To what extent does the design and delivery of the program support the achievement of outcomes?

4. To what extent does program monitoring and reporting support the achievement of outcomes?

5. What impact has the program had on expected outcomes?

Economy/Efficiency

6. To what extent do collaboration and partnerships assist in the achievement of desired outcomes?

7. Are there efficiencies in inputs towards the achievement of outcomes?

8. Are there more economical/efficient alternatives for achieving the same outcomes?

The Mid-Term National ReviewFootnote 15 conducted in 2010-11 responded to Treasury Board's core evaluation questions on relevance, namely: the ongoing need for prevention funding, consistency of the EPFA with government and departmental priorities, as well as the role of the federal government in child welfare on reserve. Thus, relevance in this evaluation is addressed through the identification of specific prevention and program needs in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia.

2.3 Evaluation Method

2.3.1 Data Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following lines of evidence:

- Literature Review

The literature review examined mostly national academic literature, as well as studies produced by organizations that have expertise in the field of child welfare and/or Aboriginal child welfare. The purpose of the review was to provide insight on the state of Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal child welfare in Canada and abroad, as well as gaps and best practices related to improving outcomes for children, families and communities. Analysis of this line of evidence was facilitated using NVivo 9 software.

- Document and file review:

This line of evidence was used to inform the review findings and assist in the development of the program profile and contextual background. The documents reviewed include, among others:

- Business Plans;

- EPFA Final Reports;

- Policy documents;

- Provincial and Aboriginal policies, programs, plans, reports, strategies and initiatives;

- Tripartite Accountability Frameworks;

- Previous audits, evaluations, Management Response and Action Plans and follow-ups;

- Terms and Conditions;

- Program and project documents (e.g.: Performance Measurement strategies, Information Management System documentation, etc.); and

- Statistical data where possible.

- Key informant interviews:

Key informant interviews were conducted to validate findings found in the literature and document reviews. Key informants were identified by the Children and Families Directorate at AANDC, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) and other key informants, and were asked to contribute any documentation that could substantiate their assertions. Analysis of this line of evidence was facilitated using NVivo 9 software.

A total of 15 people were interviewed for this evaluation, and the list can be broken down in the following manner: AANDC representatives (Headquarters and regions) (eight); representatives from FNCFS agencies and relevant organizations (five); and provincial child welfare representatives (two). Key informant interview guides are attached in Appendix B.

- Case Studies

Two case studies were conducted by Auguste Solutions and Associates Inc. to provide qualitative insights into the extent to which identified needs are being addressed, as well as the extent of effective program performance and efficiency. One case study was conducted with MFCS in Nova Scotia, and the other was conducted with the Sturgeon Lake Child and Family Services Agency in Saskatchewan.

The case studies examined program outcomes in communities by identifying factors that facilitated or hindered program success, and considered promising practices and lessons learned from front-line workers and community members.

During the case studies, the evaluators used individualized interview guides for each of the primary groups to be interviewed: the agency director, agency staff, chief and counselors, health and wellness staff, Elders and foster parents.

For each of the case studies, the interview results were tabulated and findings were produced to answer the specific evaluation questions and issues. No attempts were made to formally compare the results from the Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia case studies because of the jurisdictional differences between the two provinces. Furthermore, the Nova Scotia case study covered all of the First Nation communities in Nova Scotia, while the Saskatchewan case study was specific to the Sturgeon Lake First Nation.

Both case studies included:

- A review of linkages to other community programming and partnerships;

- A review of the Agency's Business Plan and other relevant documents;

- Interviews with FNCFS Agency staff, their Board of Directors, and community members (including chief and counselors, Elders, foster parents, etc.); and

- Community visits, including a visit to FNCFS agencies and/or other relevant community facilities.

- Surveys

A web-based/telephone survey was conducted by Auguste Solutions and Associates Inc. to FNCFS agency staff and representatives from all 67 communities in Saskatchewan and 13 communities in Nova Scotia. In total, only 17 individuals agreed to participate in the web-based survey, 11 of which agreed to participate by telephone.

Invitations were mailed to all chiefs in the participating regions and e-mail invitations were sent to each agency director. The invitations requested their participation in completing the web-based survey as well as solicited their assistance in requesting that FNCFS agency staff and community members respond as well. At least three attempts were made to reach each chief by telephone and reminders were emailed to each agency director followed by at least three telephone calls.

Data from the web-based survey was collected using SnapSurvey software and was converted into SPSS format for tabulation.

2.3.2 Considerations and Limitations

Considerations

- In evaluating child welfare services, it may have been beneficial to interview some of the families and children that were receiving support from the prevention services being provided to families and children. Because of privacy and other concerns, it was decided not to interview families and children that were receiving support but rather to interview foster parents who, for the most part, are able to provide information from the perspective of families and children.

- Case-specific information was not gathered for this evaluation as this information was not required to address the three main evaluation issues.

- The evidence provided in the evaluation must be also considered in the context of the quality of data available regarding First Nations child welfare. Documentary, literature and interview sources reiterate that there is insufficient data on the actual needs, resources, or state of care being provided, both on and off reserve. Canada does not have a national child welfare data collection system; a situation that makes analyzing comparative information a challenge.

Limitations

- Only a five agency directors agreed to be interviewed for this evaluation. Some of the reasons provided include a high workload and a general fatigue regarding audit/evaluation work.

- Both communities that agreed to participate in a case study had significant contentions with the technical report. As a result, one agency refused to have its information used in the evaluation report, and the other provided major revisions to the evaluation staff.

- A large number of agency staff and community members who were asked to participate in a web-based survey as a line of evidence for this evaluation refused on the basis that the topic is contentious and that it is difficult to express their opinions through a web-based format, resulting in only 17 individuals agreeing to participate in the survey. Given this low response rate, it was determined that the evaluation would not use the survey data as part of the evaluation.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

EPMRB of AANDC's Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Assurance Strategy. The Quality Assurance Strategy is applied at all stages of the Department's evaluation and review projects, and includes a full set of standards, measures, guides and templates intended to enhance the quality of EPMRB's work.

An advisory committee was established for the purpose of this evaluation and included representatives from EPMRB and the Child and Families Directorate at AANDC Headquarters, AANDC regional offices, the governments of Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, and a FNCFS agency in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, respectively. The purpose of the committee was to ensure that results are based on reliable and defendable evidence, anchored in appropriate methodology, and that issues are consistent with Treasury Board Secretariat policies and guidelines. The committee operated from July 2011 to November 2012, and was asked to convene as required to review and provide feedback on deliverables.

The majority of the work for this evaluation was completed by EPMRB staff, with the assistance of a consultant for the case studies and surveys. Oversight of daily activities was the responsibility of the EPMRB evaluation team, headed by a Senior Evaluation Manager. The methodology and draft final reports were peer reviewed by EPMRB for quality assurance; these reports and a key findings deck were also sent to the Advisory Committee for feedback.

3. Findings – Relevance

The Mid-Term National Review conducted in 2010-11 responded to Treasury Board's core evaluation questions on relevance, namely: ongoing need for prevention funding, consistency of the EPFA with government and departmental priorities, as well as the role of the federal government in child welfare on reserve. This evaluation built on that knowledge and focused on the most prevalent issues identified in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia.

3.1 What are the Identified Child Welfare and Prevention Needs of First Nations in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia?

3.1.1 Children in Care Needs

Finding: The main Children in Care needs in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia stem from an over- representation of First Nations children in care, a rise in complex medical needs and high cost institutional care, and a rise in older children coming into care.

Over-Representation of First Nations Children in Care

In line with national statistics, First Nations children are over-represented in both Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, both on reserve and off. In Saskatchewan overall, the average rate of Children in Care as of 2009 was 21.7 per 1,000 compared to the national average of 9.2.Footnote 16 Of this number of children in care, approximately 80 percent are Aboriginal children, and more than one quarter are served by FNCFS agencies. This represents a doubling of the number of permanent wards of the system between 2004-2009 in Saskatchewan.Footnote 17

Part of the reason for the increasing number of First Nations and Métis children coming into care, according to a 2010 Saskatchewan Child Welfare Review Panel, is the "threshold" system in place in Saskatchewan, which disqualifies many who need assistance from receiving any. In other words, those children and families in need of assistance have historically not received services unless the situation reached a crisis point. While the Province of Saskatchewan is working to change this system, FNCFS agencies have offered some preventive services, even prior to the EPFA where capacity existed, to deal with the need. Between 2009 and 2011, 11 of the 17 FNCFS agencies in Saskatchewan reported an increase in the number of children coming into their care, while six of the 17 reported a decrease.

In Nova Scotia both on and off reserve, Mi'kmaw children represent approximately 16 percent of Children in Care though only six percent of the total child population is Mi'kmaw.Footnote 18 Other statistics for Nova Scotia have shown that Mi'kmaw children in Nova Scotia are between 3.3 percent and six percent more likely to be removed from the home than non-Mi'kmaw children.Footnote 19 MFCS reported that as of March 2012, MFCS had a case load of 669, which includes children still within the parental home and children in care out of the parental home.Footnote 20

Complex Medical Needs and the Rise of High Cost Institutional Care

Many First Nation children coming into care require an elevated level of specialized care, and must, at times, be placed in high cost facilities off reserve that can support their needs. It is reported that children in the child welfare system in Saskatchewan have a much higher than average incidence of disabilities and special needs compared to the national average.Footnote 21 Some of the reasons provided for this include children born with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder or who are otherwise substance-dependent at birth, which can lead to severe and complex medical needs throughout their life.

The costs for these placements are reported to be on the rise in both provinces examined. Compared to other forms of care for which AANDC collects data, institutional care costs are much higher, and have risen significantly in Saskatchewan since 2007 (see Figure 1). At the time that the Saskatchewan Framework was signed, approximately $20 million of the $28 million in maintenance costs were for institutional care.Footnote 22 Similar concerns were raised in Nova Scotia, though data was not sufficiently available to report on this.

Figure 1: Cost of Children in Care in Saskatchewan by Type of Care, 2007-2011

Comparison of Total Dollars ($000)

Text description of Figure 1

This figure is a graph comparing the cost in dollars of three different types of child care, including foster care, institutions, and kinship care, from 2007 to 2011. There are four year categories represented by independent lines: 2007-08, 2008-09, 2009-10, and 2010-2011. The years are represented on the x-axis and the dollar amounts are represented on the y-axis.

The cost of kinship care increased from $0 in 2007-08 to approximately $2 million in 2008-09. Between 2008-09 and 2010-2011, the cost of kinship care increased to approximately $3 million.

The cost of foster care decreased from approximately $8 million in 2007-08 to approximately $6 million in 2008-09. Between 2008-09 and 2010-2011, the cost of foster care increased to $8 million once again.

Institutions represent the most costly type of child care and also represent the fastest growing type. The cost of institutions increased from slightly below $20 million in 2007-08 to approximately $21 million in 2008-09. Between 2009-10 and 2010-2011, the cost of institutions increased from $23.5 million to approximately $26 million.

Depending on the complexity of the medical needs, parents have, at times, had no choice but to send their children into institutional care. Where there has been a lack of placement options, agencies have had to be resourceful in coming up with child care solutions. Three instances were reported in Saskatchewan where children were placed in nursing homes to accommodate their needs.

Where the cases are less severe, a small number of agencies in Saskatchewan have opened group homes on reserve with the goal of bringing down institution care costs while keeping their children in the community. A few other agencies expressed an interest in opening group/safe homes on reserve, though their funding does not allow for capital infrastructure. When possible, agencies with this interest have rented spaces in their communities.

Rise in Older Children Coming into Care

According to several business plans in Saskatchewan, agencies have seen a rise in older children coming into care. This has been attributed to an increase in the extent and severity of gang violence in communities, as well as substance addictions. Research conducted by the Canadian Center for Justice Statistics suggests that the violent crime rate on reserve in Saskatchewan is about five times higher than the provincial rate.Footnote 23 Research also suggests that almost one-third (31 percent) of Aboriginal youth accused of criminal activity were aged 12 to 17 years.Footnote 24,Footnote 25

In 2006, the law enforcement community in Saskatchewan reported that given the demographic trends and the current youth gang problems, future recruitment of youth to gangs and gang related crimes would increase among Aboriginal communities in Saskatchewan. As it stands, Saskatchewan is reported to have the highest per capita concentration of youth gang members (1.34 per 1,000 people) in Canada,Footnote 26 with 96 percent of members being of Aboriginal descent.Footnote 27 Police and Aboriginal organizations have further noted an increase in the number of female gang members in several provinces, including Saskatchewan.Footnote 28

While Nova Scotia does report having some Aboriginal gang violence, it is largely concentrated in the Halifax region and was not noted as a major concern for MFCS.

Given the young age at which Aboriginal youth generally enter into gangs, several Saskatchewan agencies noted that parents are often ill-equipped to handle such cases, and will, in some cases, voluntarily relinquish care of their children to FNCFS agencies.

3.1.2 Parental/Community Issues

Finding: Poverty, housing, substance abuse, mental health, child abuse and neglect, poor parenting skills and a lack of alternative care options were cited as the most common parental and community issues facing First Nations communities in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia.

Poverty

According to the literature, there is no better predictor of involvement in the child welfare system than poverty.Footnote 29 In line with other parts of Canada, poverty levels are deeper among First Nation people than for Métis and non-Aboriginal people living in Saskatchewan, and poverty levels for First Nation people are reportedly deeper on reserve than off reserve.Footnote 30 Similarly, using Statistics Canada's Low Income Cut-Off and the Market Basket Measure, it was estimated that the Mi'kmaw in Nova Scotia face higher rates of poverty than the rest of the province – 51 percent of unattached First Nation women lived below the Low-Income Cut Off, compared to only 13.8 percent of the total population.Footnote 31 The significance of this statistic lies in the fact that Mi'kmaw households on reserve in Nova Scotia were most likely to be lone-parent households, at 31 percent.Footnote 32 Moreover, income was shown to be an important factor in streaming children towards removal. The average income in Nova Scotia is $46,000 per year, while 95 percent of families who had their children removed made under $25,000 per year.Footnote 33 From statistics available on poverty on reserve, approximately 55 percent of homes in Nova Scotia and 56 percent in Saskatchewan were at or below the Low-Income Cut Off line.Footnote 34

Agencies state that some families are unable to meet their basic needs (i.e. food, fuel for heating, transportation to medical appointments, etc.) and find themselves unable to care for their children. This is exacerbated by the lack of economic opportunities in some communities, which, as one key informant noted, makes it easy for the family to slide back into its unhealthy behaviours.

Housing/Foster Homes

Housing issues and overcrowding are some of the main factors for why children come into care. In Canada, Aboriginal homes are approximately four times more likely than non-Aboriginal homes overall to require major repairs, and mould contaminates almost half of First Nations homes.

According to the 2006 Census, 83 percent of homes on reserve in Saskatchewan are in need of repairs, 52 percent of which are considered major repairs. For Nova Scotia, 65 percent of homes on reserve are in need of repairs, 32 percent of which are major repairs.Footnote 35

In Saskatchewan, overcrowding is reported to be putting strain on the housing structures, which can lead to other problems such as black mould and a lack of quality water. Such conditions can lead to severe medical problems and intensify the number of children coming into care with specialized needs. Overcrowded housing is also linked with an increase in family violence and child abuse. In this province, 36 percent of First Nations people on reserve lived in overcrowded conditions.Footnote 36 The Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations reports that there is a lack of approximately 1,400 houses to meet the demand on reserve.

The Province of Saskatchewan has recently raised its standards for foster homes, and some agencies report that between the housing shortage and the new standards, some of the families willing to foster on reserve will not meet the proper criteria. The overcrowding of foster homes has been a contentious issue in Saskatchewan, a condition which has steadily worsened over the past two decades.Footnote 37 While this problem exists mainly off reserve, and the provincial government is taking steps to rectify the situation, it is a worrisome issue for FNCFS agencies in the province when children are placed off reserve because of the lack of available homes on reserve.

While housing was reported as an issue in Nova Scotia, its severity and impact on the number of children coming into care or foster care could not be determined.

Abuse, Neglect and Parenting Practices

The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect for 2001, 2003 and 2008 show that neglect is the most likely form of abuse among Aboriginal maltreatment cases at over 50 percent of substantiated cases, and that physical abuse is one of the least likely forms of abuse found in Aboriginal communities. This finding is reflective of key informant responses in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. A review of existing literature supports this finding and suggests that neglect is more common in First Nations than in non-Status Indian, Métis or Inuit families.Footnote 38 Literature also points to the negative effects that abuse and neglect can have on children, as they are more likely to grow up having mental illness, drug and alcohol misuse, risky sexual behaviour, obesity and criminal behaviour persisting into adulthood.Footnote 39

The 2008 Canadian Incidence Study reports that First Nations children are investigated and their investigations are substantiated at higher rates than non-Aboriginal children. First Nations children are more likely to receive ongoing services after a substantiated investigation than non-Aboriginal children and are more likely to be removed from their home than non-Aboriginal children.Footnote 40 Key informants in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia noted that in many instances families are brought to the attention of the agencies on repeated occasions.

At the root of this neglect, several key informants and the literature suggest that it is the residual effects of the Residential School system, where many students lost their Aboriginal identity and the opportunity to observe normal parenting practices, which impeded their own ability to parent their children in a healthy way. Much of the prevention programming offered through EPFA funding in Saskatchewan, and to the extent possible in Nova Scotia, is focused on rebuilding communities and assisting parents to care for their children.

Addictions/Mental Health

Similar to national statistics, alcohol and drug abuse (prescription and illicit), along with a lack of program supports for mental health for parents who have suffered trauma, are common in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, and are among the main reasons cited when children are brought into care. In Nova Scotia, parental alcohol and drug addictions were cited as the primary reason First Nations children came into care. Over half of the business plans reviewed noted a shortage of supportive programming for referral of clients for mental health and addictions. Business plans also referred to the isolated nature of many First Nation communities, which means that clients must travel long distances in order to receive the care they require when it is not available in the community, and are often put on long waiting lists.

It is well documented that there is often a link between child maltreatment and neglect in Aboriginal communities to addiction and mental health issues, although in-depth research in this field is limited.Footnote 41 The Office of the Auditor General report of 2008 (Chapter 4) notes an increasing number of infants are born addicted to drugs in First Nation communities.Footnote 42

Foster Parents / Kinship Care / Adoption

In both Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, it is reported that there is a need for more alternative care options on reserve. Alternative care options can include foster parents, kinship care and adoption, and are all supported under the EPFA.Footnote 43

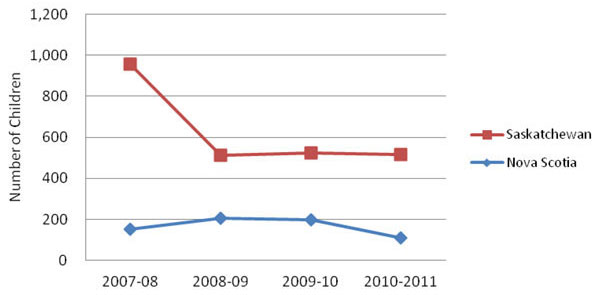

The number of children being placed in foster homes has leveled off in Saskatchewan after a sharp decline between 2008 and 2009, and has decreased by almost half in Nova Scotia between 2010 and 2011 (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of Children in Foster Care in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia, 2007-2011

Number of Children in Foster Care, 2007-2011

Text description of Figure 2

This figure is a graph comparing the number of children in foster care in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia between 2007 and 2011. There are four year categories represented by independent lines: 2007-08, 2008-09, 2009-10, and 2010-2011. The years are represented on the x-axis and the number of children is represented on the y-axis.

In Nova Scotia, the number of children in foster care increased from approximately 180 to 200 between 2007-08 and 2008-09. From 2008-09 to 2009-10, the number of children in foster care remained the same, at 200. Between 2009-10 and 2010-2011, the number of children in foster care decreased from 200 to approximately 100.

In Saskatchewan, the number of children in foster care decreased from approximately 950 in 2007-08 to approximately 500 in 2008-09. From 2008-09 to 2010-2011, the number of children in foster care in Saskatchewan remained relatively the same.

There are reportedly not enough foster homes available on reserve to meet the current need. Some of the reasons provided for the lack of available foster homes in Nova Scotia include:

- An increase in the number of children requiring temporary and longer-term placements outside the family home;

- Younger families are less inclined to become involved;

- The police security check process has become more demanding; and

- The training demands, particularly for those who care for children with special needs, are both challenging and time-consuming.

As a mitigation strategy, a toll-free number is advertised for the recruitment of foster parents. As it stands, over 100 Mi'kmaw children are currently placed in non-Aboriginal foster homes.

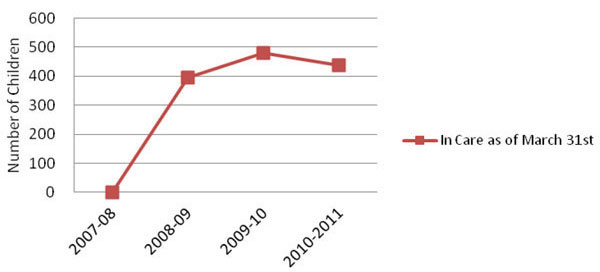

In Saskatchewan, a few agencies reported that allocations to foster care families are not high enough to cover costs in northern/remote areas. The higher cost of food and other necessities, such as diapers and formula, were cited as examples whose costs could be more than double than what is paid in the South. Moreover, it was also noted that that there are few supports for people who would like to serve as foster parents. New requirements from Ministry of Social Services related to foster home training, including a 3-hour session with Elders, have led to an increase in trained homes in a few communities. Finally, a lack of day care subsidies for foster parents means that some families who are willing to foster are unable to do so, because both parents are employed; one agency in Saskatchewan is paying this to keep foster parents, although this is not a reimbursable expense under the agreement. As for kinship care, the number of kinship care cases has risen significantly in Saskatchewan over the past few years, signaling a move towards more family-oriented care when possible (figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of Children in Kinship Care in Saskatchewan, 2007-2011

Number of Children in Kinship Care in Saskatchewan, 2007-2011

Text description of Figure 3

This figure is a graph indicating the change in the number of children in kinship care (as of March 31st) in Saskatchewan between 2007 and 2011. There are four year categories represented by independent lines: 2007-08, 2008-09, 2009-10, and 2010-2011. The years are represented on the x-axis and the number of children is represented on the y-axis.

From 2007-08 to 2008-09, the number of children in care increased from 0 to 400. Between 2008-09 and 2009-10, the number of children in care increase from 400 to approximately 480. Between 2009-10 and 2010-2011, the number of children in kinship care decreased from approximately 480 to approximately 430.

Statistics on kinship care and adoption were not available for Nova Scotia, though kinship care and custom adoptions are considered priorities for MFCS. Statistics were similarly unavailable for post-adoption subsidies and supports in Saskatchewan FNCFS agencies.

3.2 What are the Program Supports and Capacity Needs in Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia?

3.2.1 Capacity Needs