Archived - Summative Evaluation of the Post-secondary Education Program

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: June 2012

PDF Version (737 Kb, 75 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings – Performance

- 5. Evaluation Findings – Efficiency and Economy

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Survey Guide

- Appendix B - Interview Guides

- Appendix C - Case Study Tools

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| ACED |

Aboriginal Community Economic Development Program |

| CFA |

Comprehensive Funding Arrangement |

| DFNFA |

DIAND/First Nations Funding Arrangement |

| DIAND |

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| EPMRC |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee |

| ESE |

Elementary/Secondary Education |

| FNPP |

First Nations Partnership Program |

| HQ |

Headquarters |

| ISSP |

Indian Studies Support Program |

| NVIT |

Nicola Valley Institute of Technology |

| OAG |

Office of the Auditor General |

| PSE |

Post-secondary Education |

| PSSSP |

Post-secondary Student Support Program |

| SFU |

Simon Fraser University |

| UCEP |

University and College Entrance Preparation |

Executive Summary

This summative evaluation of the Post-secondary Education (PSE) Program was conducted in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13. It follows a formative evaluation of the PSE Program in 2010, which provided a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC).

This evaluation was conducted concurrently with the summative Evaluation of Elementary/Secondary programming in order to obtain a holistic understanding of AANDC's suite of education programming and its impact on First Nation and Inuit communities.

The primary objective of AANDC's PSE programming is to help First Nation, Inuit and Innu learners achieve levels of education comparable to other Canadians by providing eligible students with access to education and skill development opportunities at the post-secondary level.

AANDC's post-secondary education programming is primarily funded through two authorities: Grants to Indians and Inuit to support their post-secondary educational advancement, and Payments to support Indians, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education – Contributions to support the post-secondary educational advancement of registered Indian and Inuit students.

The evaluation examined all three components of post-secondary education programming, namely, the Post-secondary Student Support Program, the University and College Entrance Preparation, and Indian Studies Support Program.

In line with Treasury Board Secretariat requirements, the evaluation looked at issues of relevance (continued need, alignment with government priorities, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities), performance (effectiveness) as well as efficiency and economy.

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of six lines of evidence: case studies, data analysis, document and file review, key informant interviews, literature review, and surveys (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix).

Three contractors were contracted to handle specific lines of evidence for which they have expertise. Donna Cona Inc. undertook key informant interviews and case studies; Harris/Decima conducted surveys; and the University of Ottawa carried out a meta-analysis of available literature. The evaluation team worked closely with them to determine the most appropriate and rigourous approaches to the methodologies, and conducted most of the final analysis in-house.

Key Findings

The findings indicate a considerable need for AANDC to review its current approach to post-secondary to better ensure short-term successes and long-term benefits to First Nation and Inuit people and to the Canadian economy and society broadly. To that end, this evaluation found the following:

Relevance

- There is a continued need to fund and otherwise provide resources to First Nation and Inuit students seeking post-secondary education based on a growing Aboriginal population, coupled with projected labour market needs, and the potential for improvements in First Nation and Inuit educational outcomes to contribute to meeting those needs.

- Education authority activities are generally aligned with Government of Canada priorities; however, recent major reforms are reflective of the need to better align activities and better ensure improvements in student success.

- The roles and responsibilities of the federal government around post-secondary education remain unclear.

Performance - There is evidence of some improvement in the achievement of outcomes for post-secondary with respect to interest in enrollment, and some indications of success. There is a strong need, however, for data collection improvements to allow for a reliable assessment of student enrollment and results.

- There is evidence to suggest that community-based programming is occurring and providing positive results for students and communities.

- The most common challenges facing First Nation students include academic readiness for post-secondary studies, access to finances for tuition and other costs, and a difficult transition period. Evidence further suggests the critical importance of family and community support, and the benefits of culturally-relevant curricula and transitional support from institutions.

- The current approach to funding post-secondary students is problematic in that it does not allocate funding based on need, and that there is little accountability for the degree to which post-secondary funds are used to fund students.

Efficiency and Economy - The current approach to programming may not be the most efficient and economic means of achieving the intended objectives of PSE programming.

Based upon these findings, it is recommended that AANDC:

- Develop a strategic, transparent framework to ensure clear definitions of roles, responsibilities, commitments, funding approaches and accountabilities for post secondary education;

- Further support partnership development with First Nations, education organizations and institutions to facilitatestudent transitions and support.

- Work to develop data collection methods that allow for the reliable assessment of student enrollment and success.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Summative Evaluation of Post-Secondary Education Program

Project #: 1570-7/09058

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop a strategic, transparent framework to ensure clear definitions of roles, responsibilities, commitments, funding approaches and accountabilities for post-secondary education. 2. Further, support partnership development with First Nations, education organizations and institutions to facilitatestudent transitions and support. |

We concur | Stephen Gagnon, Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP | Start Date: June 2012 |

| In Budget 2010, the Government committed to engage in a new approach to providing support to First Nation and Inuit post-secondary students to ensure that the students receive the support they need to pursue higher education. The new approach will be effective and accountable, and will be coordinated with other federal student support programs. The findings in this evaluation will be considered as the Department develops options for education reform. |

Completion: Fall 2014 |

||

| 3. Work to develop data collection methods that allow for the reliable assessment of student enrolment and success. | We concur. | Stephen Gagnon, Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP | Start Date: July 2012 |

| The Education Branch agrees that the data on student enrollment and success is not reliable. The Branch has revised its data collection instruments (DCIs) as well as the timing of the reporting process to improve the reliability and completeness of the data. The new DCIs will apply from 2012-2013 onwards, with the first set of data to be submitted by recipients in June 2013. | Completion: July 2013 |

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed by:

Françoise Ducros

Assistant Deputy Minister

Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This summative evaluation of the Post-secondary Education (PSE) Program was conducted in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13. It follows a formative evaluation of the PSE Program in 2010, which provided a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) and was required to approve the continuation of terms and conditions of the program as of March 31, 2010.

The evaluation was conducted concurrently with the summative Evaluation of Elementary/Secondary (ESE) Programming in order to obtain a holistic understanding of AANDC's suite of education programming and their impact on First Nation and Inuit communities. This approach allowed the evaluation team to minimise costs and reduce the burden for individuals and communities by collecting all the information at one time.

In line with Treasury Board's Directive on the Evaluation Function, the evaluation looked at issues of relevance (continued need, alignment with government priorities, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities), performance (effectiveness), as well as efficiency and economy.

All three components of PSE programming were included as part of this evaluation, namely, the Post-secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP), the University and College Entrance Preparation (UCEP), and Indian Studies Support Program (ISSP).

PSSSP is the primary component of the PSE Program. PSSSP provides financial support to First Nation and Inuit students who are enrolled in post-secondary programs, including: community college and CEGEP diploma or certificate programs; undergraduate programs; and advanced or professional degree programs.

UCEP provides financial support to First Nation and Inuit students who are enrolled in UCEP programs to enable them to attain the academic level required for entrance to degree and diploma credit programs.

ISSP program provides Indian organisations, Indian post-secondary institutions and other eligible Canadian post-secondary institutions with financial support for the research, development and delivery of college and university level courses for First Nation and Inuit students.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the Parliament of Canada legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians." Canada exercised this authority by enacting the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, the enabling legislation for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary education services to Indian children living on reserves. Thus, the Indian Act (1985) provides the Department with a legislative mandate to support elementary and secondary education for registered Indians living on reserve.

Since the early 1960s, AANDC has sought incremental policy authorities to support the improvement of the socio-economic conditions and overall quality of life of registered Indians living on reserve. Activities have generally included support for Indian and Inuit access to, and participation in, PSE as well as support for culturally appropriate education. AANDC considers its involvement in post-secondary education as a matter of policy.

Although there have been significant gains since the early 1970s, First Nation participation and success in post-secondary education still lags behind that of other Canadians. Drop-out rates are higher for First Nations than other Canadian students. Increasing Indian and Inuit retention rates and successes at the post-secondary programming level, as well as facilitating Indian and Inuit participation in, and achievement of, post-secondary education supports the strategic goal of greater self-sufficiency, improved life chances, and increased labour force participation.

AANDC's post-secondary programming is primarily funded through two authorities: Grants to Indians and Inuit to support their post-secondary educational advancement, and Payments to support Indians, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education – Contributions to support the post-secondary educational advancement of registered Indian and Inuit students.

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The primary objective of AANDC's PSE programming is to help First Nation, Inuit and Innu learners achieve levels of education comparable to other Canadians by providing eligible students with access to education and skill development opportunities at the post-secondary level. The desired results are greater participation of these individuals in post-secondary studies, higher graduation rates from post-secondary programs and higher employment rates.

In AANDC's Program Activity Architecture, education falls under the strategic outcome "The People," whose ultimate outcome is "individual and family well-being for First Nations and Inuit." Education is its own Program Activity, which includes post-secondary education.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The management of education programming at AANDC is undertaken by the Education Branch in the Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector.

AANDC provides funding for PSE to Chiefs and Councils and to the organizations designated by Chiefs and Counsellors. AANDC may also enter into funding agreements with public or private organizations engaged by or on behalf of First Nation or Inuit communities to administer PSE programs. When Chiefs and Councils choose to have AANDC deliver services on reserve or administer some components of the PSSSP program funding, AANDC may make grant payments directly to individual registered Indian (First Nation or Innu) and Inuit participants. The Department may also grant payments directly to individual First Nation students who are not members of a band (registered in the General Register) and to individual Inuit students who are normally resident outside Nunavut or the Northwest Territories.

Eligible recipients of funding are registered Indians and Inuit students who ordinarily reside in Canada, have been accepted by an eligible post-secondary institution into either a degree or certificate program, or a university or college entrance preparation program, and enrol with and maintain continued satisfactory academic standing within that institution. Applicants for UCEP must not have previously received financial support from AANDC's PSE Program, although an exemption may be given for medical reasons.

PSE program funding is not available to registered Indians or Inuit who are eligible for assistance under special arrangements for post-secondary assistance, such as the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, the Northwest Territories Student Financial Assistance Program or the Nunavut Student Financial Assistance Program.

Post-secondary education institutions are also eligible recipients in cases where a student recipient signs an agreement authorizing AANDC to transfer funds directly to the post-secondary institution to cover the cost of her or his tuition and compulsory fees.

PSE is almost 100 percent administered by the First Nations band councils or their designated organizations; First Nations determine and prioritize their own student selection criteria and also determine the individual level of student funding.

1.2.4 Program Resources

In 2010-11, AANDC spent nearly $1.8 billion on education,Footnote 1 $316 million of which was spent on PSE programming. Table 1, below, provides a breakdown of total PSE funding from 2005-06 to 2010-11.

| AANDC PSE Programming | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISSP | $19,905,403 | $20,113,247 | $21,036,972 | $20,967,663 | $21,077,717 | $21,005,648 |

| PSSSP/UCEP | $280,276,652 | $283,254,203 | $288,189,242 | $289,467,807 | $292,206,068 | $295,429,988 |

| TOTAL PSE FUNDING | $300,182,055 | $303,367,450 | $309,226,214 | $310,435,470 | $313,283,785 | $316,435,636 |

Education programming is funded through annual Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (CFA) and five-year DIAND/First Nations Funding Agreements (DFNFA). All components of the Post-secondary Education Program are eligible under the following funding authorities flowing from these arrangements: grants, set contribution, fixed contribution, and block contribution.Footnote 2 An exception to this is ISSP, which is only eligible under set contribution funding.

Effective April 1, 2011, AANDC began using additional fixed, flexible and block contribution funding approaches for transfer payments to Aboriginal recipients, as described in the Directive on Transfer PaymentsFootnote 3 and according to departmental guidelines for the management of transfer payments. Prior funding for PSE through Alternative Funding Arrangement or Flexible Transfer Payment mechanisms will remain in effect, as required, until the expiration of existing funding arrangements that contain these mechanisms.

The allocation of program funding involves the distribution of funds from Headquarters (HQ) to the regions and from the regions to the recipients. The DFNFAs are formula-driven, and are consistent throughout the country. The CFA allocation model for the program, on the other hand, varies sometimes significantly by region.

In terms of the allocation of funds from HQ to the regions, program funding is a component of each region's annual core budget. The Education Branch does not determine the amount of program funding to be allocated to each region. This is the responsibility of the Resource Management Directorate in Finance at HQ. National budget increases (currently two percent annually) are allocated to each region in proportion to their existing budgets. The regions have the authority to allocate funds across the various programs included in their core budget and ultimately decide the extent of program funding to provide to their recipients.

1.3 Current Evaluation

The current evaluations of ESE and PSE looked at the entire suite of education programming offered by AANDC. In the past, AANDC has evaluated components of its education programming, such as the Evaluation of the First Nations SchoolNet Program (2009), the Evaluation of the Special Education Program (2007), the Summative Evaluation of the Cultural Education Centres Program (2005), and the Summative Evaluation of Band-Operated and Federal Schools (2005). While evaluating programs from this lens has its benefits, the result is a lack of understanding of how all programs affect overall student outcomes. It is expected that evaluating Aboriginal education in this light will provide the Department with a clearer sense of the current state of Aboriginal education and insight on future direction.

Internally, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch's (EPMRB) evaluation work is informed by its Engagement Policy that provides Branch staff with a framework for including Aboriginal people and organizations in the evaluation process. The purpose of the policy is to:

- ensure Aboriginal involvement in, and contribution to, relevant and meaningful evaluations;

- define the roles and responsibilities of all parties;

- enhance communication and improve relationships between the Department and Aboriginal people and organizations; and

- ensure that reporting requirements placed on recipients of AANDC programs related to the evaluation are kept to the minimum possible.

The underlying principle is that, for evaluations to be relevant to, and have meaning for, Aboriginal people, Aboriginal people need to be fully involved in the evaluation process. As part of this evaluation, Aboriginal involvement was attained through interviews, surveys and case studies (including focus groups).

Furthermore, an Advisory Committee was established, composed primarily of national First Nation and Inuit education organisations, as well as representation from AANDC. The purpose of the Advisory Committee was to provide guidance and insights on the development of evaluation tools, and on broader interpretation of findings and forming recommendations. The Advisory Committee representatives met and/or were provided with documentation at various stages of the evaluation process to discuss and provide advice on:

- Terms of Reference

- Methodology Reports

- Acquisition of Qualified Consultants

- Potential Key Informants, Case Study Communities and Literature

- Technical Reports

- Evaluation Findings

- Draft Final Evaluation Report

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined all three components of the PSE programming: PSSSP, UCEP, and ISSP. The Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) on May 14, 2010. This evaluation provides information on program relevance, performance, and efficiency and economy to support the management of program authorities in compliance with the Policy on Transfer Payments.

Three consultants, Donna Cona Inc., Harris/Decima and the University of Ottawa were contracted to undertake primary data collection (see Section 2.3). Data collection and analysis was undertaken between September 2010 and April 2012.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the revised evaluation questions approved at EPMRC in September 2010, the evaluation focused on the following issues:

- Relevance

- Is there an ongoing need for the program?

- Is the program consistent with government priorities and AANDC strategic objectives?

- Is there a legitimate, appropriate and necessary role for the federal government in the program?

- Performance

- To what extent have intended outcomes been achieved as a result of the program?

- To what extent has the program influenced the constructive engagement and collaborative networks to further education and skills development?

- What are the factors (both internal and external) that have facilitated and hindered the achievement of outcomes? Have there been unintended (positive or negative) outcomes? Were actions taken as a result of these?

- To what extent has the design and delivery of the program facilitated the achievement of outcomes and its overall effectiveness?

- Efficiency and Economy

- Is the current approach to programming the most economic and efficient means of achieving the intended objectives?

- How could the program be improved?

2.3 Evaluation Methodology

The following section describes the data collection methods used to perform the evaluation work, as well as the major considerations, strengths and limitations of the report and quality assurance.

2.3.1 Data Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of six lines of evidence: case studies, data analysis, document and file review, key informant interviews, literature review, and surveys (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix). All lines of evidence were collected for this evaluation and the Summative Evaluation of Elementary/Secondary Education simultaneously to minimise costs and reduce the burden for individuals and communities by collecting all the information at one time.

- Case Studies:

A total of 14 case studies were conducted by Donna Cona Inc. for both Elementary/Secondary and Post-secondary Education evaluations. Case studies provided qualitative insights into whether intended impacts of education programs, policies and initiatives are occurring. These case studies also allowed for the identification of needs and best practices in order to determine where disparities exist in the quality of services being provided to First Nation and Inuit communities across the country.

Seven case studies were conducted using a regionally-based approach, where one community was selected randomly for each AANDC region (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Atlantic) while attempting to acquire a general representation of varying community sizes, local economies, and isolation. In these case studies, Donna Cona Inc. was asked to take a holistic approach to education in the community to gain a comprehensive understanding of issues facing individuals in pursuing post-secondary education broadly, but also to gain insight into specific barriers as well as successes and innovations. Case study tools were designed by Aboriginal researchers and customised to include various methods of communication if the respondent so chose. Inuit-specific tools were also developed for Inuit case studies.

The regionally focused case studies included, but were not limited to, participation from:- Chiefs and/or member(s) of band councils responsible for education profiles;

- Education office/department managers and staff (where applicable) and/or persons responsible for elementary/secondary / post-secondary school management (where applicable);

- School principals;

- School counsellors, on-reserve elementary and secondary teachers, cultural centre's staff and Elders;

- Parents of elementary/secondary or post-secondary students; and

- Students, aged 16 and over, who are receiving funding for post-secondary programming.

Similar to the regional case studies, the thematic case studies included, but were not limited to, participation from individuals with similar portfolios to those listed above.

Prospective communities or organisations were contacted by AANDC in writing and subsequently contacted by Donna Cona Inc. to confirm whether participants were interested. Communities wishing to participate worked directly with the consultant to organise the site visit and information sharing. Participants were asked if they were willing to have their interviews recorded. Willing participant's audio files were securely stored electronically, and hand-written notes were securely stored for those not wishing to be recorded. Data was stripped of personal identifying information and securely transmitted to AANDC EPMRB for analysis and interpretation using NVivo 9 Qualitative Analysis Software. Data was stored in accordance with departmental guidelines on data storage, to be destroyed after five years, and are handled as "Protected B"Footnote 4 information. Responses were organised by evaluation questions and open-ended thematic elements.

Concise case study reports were also completed by Donna Cona for each regional and thematic case study, which included community and/or program specific profiles, as well as relevant data and statistics. A technical report of case study analysis was conducted by EPMRB and reviewed by Donna Cona. - Data Analysis:

A database was created by EPMRB using an extraction of the National Post-secondary Education System for fiscal years 2003-04 to 2010-11. Data were structured to analyse student-level data (with identifiers removed), including type of program, year of academic studies and completion status. Data were further organised to garner regional and national trends on post-secondary student outcomes. - Document and File Review:

A document and file review was undertaken by EMPRB and included, but was not limited to, internal policy documents, the Departmental Performance Report, the Report on Plans and Priorities, Budget announcements, previous audits and evaluations, the Education Performance Measurement Strategy, Office of the Auditor General (OAG) reports, annual reports, project files, Regional Health Survey publications, Education Information System documentation, the Final Report of the National Panel on First Nations EducationFootnote 5 and other administrative data. Relevant documents were scanned for content relating to key evaluation questions and the analysis was triangulated with other lines of evidence. - Key Informant Interviews:

A total of 40 interviews were conducted by Donna Cona Inc. with the following key informants: six AANDC HQ, 11 AANDC region, and 23 First Nation organizations. The purpose of key informant interviews was to obtain a better understanding of the results of education programming supported by AANDC and its impact on First Nation and Inuit communities. Key informants further helped to identify other potential key informants and communities for case studies.

Prospective key informants were contacted by AANDC EPMRB in writing and then subsequently contacted by Donna Cona Inc. to establish their willingness to participate. Those wishing to participate negotiated a time and interview process with the consultant. Participants were asked of their willingness to be recorded. Willing participants' audio files were securely stored electronically, and hand-written notes were securely stored for those not wishing to be recorded. Data was stripped of personal identifying information and securely transmitted to AANDC EPMRB for analysis and interpretation using NVivo 9 Qualitative Analysis Software. Data were stored in accordance with departmental guidelines on data storage, to be destroyed after five years, and are handled as "Protected B"Footnote 6 information. Responses were organised by evaluation question and open-ended thematic elements. - Literature Review:

Members of the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa conducted a "Meta-Analysis of Empirical Research on the Outcomes of Education Programming in Indigenous Populations in Canada and Globally," which included a comprehensive assessment of literature (published and unpublished) over the past 10 years, and emphasized peer reviewed empirical research related to educational outcomes for students in First Nations and other Aboriginal populations in Canada. The purpose of the review was to provide insight on the impacts of policies and programming in education (curricula, investments, governance) on student success, as well as economic integration.

Following this initial analysis, it was determined that a supplementary literature reviewFootnote 7 would be conducted by EPMRB to provide further insight on the following themes:- Jurisdiction and control in First Nation education

- Education systems and second- and third-level services

- Early childhood education

- Adult learning and higher education

Other sources, such as websites, conference proceedings and working group papers, were also included where they proved useful in providing context or in identifying emerging research and issues. - Surveys:

Surveys were undertaken by Harris/Decima to gain insights from education administrators and post-secondary students, beyond what could be obtained with key-informant interviews. A total of 113 surveys were completed with education authorities/managers, tribal councils and post-secondary students.

Maximum confidence in the generalisability of education administrator survey results (approximately 600 in total) would require a minimum sample size of approximately 200-225 respondents. Based on an anticipated response rate of 30 percent, it was decided that EPMRB would attempt to recruit contacts from all First Nation communities in Canada to participate. In attempting to produce accurate contact information for all First Nation education administrators, EPMRB was able to gather contact information for 520 of 616 First Nations across Canada. EPMRB contacted all prospective participants in writing and then followed up via telephone to gage interest in participating. Those agreeing to participate were given the choice to complete their survey online or via telephone. They were also asked if they would be willing to assist Harris/Decima in forwarding a survey to post-secondary students who have been funded in their community over the past five years.Footnote 8 Details were logged and sent to Harris/Decima, who then followed up with participants.

Survey results were compiled by Harris/Decima, stripped of any identifying information and analysed by AANDC using PASW 18 Statistical software and NVivo 9 Qualitative software for the open-ended responses. A total of 16 follow-up interviews were also conducted with respondents who agreed to elaborate on some of the qualitative answers provided in their surveys. Qualitative data from the survey and its follow-up interviews were coded and analysed in a consistent fashion as with case studies and interviews.

In terms of regional representation among the 113 participants, regions were generally represented proportionate to the number of reserves in each, but with Ontario and Alberta somewhat overrepresented and Quebec underrepresented.

2.3.2 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

Since the evaluation builds upon the critical analysis of existing data, it also favours reductions in the reporting burden on First Nations communities. Reducing the reporting burden for recipients is a key priority for AANDC and for the Government of Canada at large.

This evaluation further considered AANDC's Sustainable Development Strategy'sFootnote 9 objective of enhancing social and economic capacity in Aboriginal communities through educational programming, with particular emphasis on factors affecting Aboriginal graduation rates in post-secondary institutions.

The evaluation also adhered to AANDC's Policy on Gender Based AnalysisFootnote 10 by analysing multiple variables based on gender. Where there are gender differences, they are discussed in the relevant sections of this report.

This evaluation comes at a time when several reforms for First Nations education are underway or being considered, such as "Reforming First Nation Education" beginning in 2008 and actions that will be taken as a result of the National Panel on First Nation Elementary and Secondary Education for Students on Reserve. While this evaluation focuses primarily on outcomes to date, it also discusses priorities moving forward.

Survey Respondent Selection: While every attempt was made to have a broad representative sample of First Nation education managers/directors, it is expected that a degree of respondent bias exists, as selection was not truly random, and those agreeing to participate may or may not have views aligning with those not agreeing to participate, or those we were unable to reach. Additionally, given that respondents were asked to send a survey link to post-secondary students on behalf of the evaluation team, there is no way to know how many students actually received the survey, and no follow-up protocol was available for this group. Unfortunately only 42 surveys were received from post-secondary students.

AANDC Internal Database Limitations: Post-secondary student data are uploaded by bands and tribal councils to AANDC and there is no verification at the departmental level for accuracy or completeness. The data held by AANDC cannot be used to establish broad statistical inferences as not all students' data are recorded consistently over time, and the system does not capture all First Nation students attending post-secondary. Trend analysis is only possible for students whose data has remained in the system for the full duration of their studies. It is not known what proportion of First Nation post-secondary students this represents.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

EPMRB of AANDC's Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority for the PSE evaluation, and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy, outlined in Section 1.3, and Quality Assurance Strategy (QAS). The QAS is applied at all stages of the Department's evaluation and review projects, and includes a full set of standards, measures, guides and templates intended to enhance the quality of EPMRB's work.

Oversight of daily activities was the responsibility of the EPMRB evaluation team, headed by a Senior Evaluation Manager. The EPMRB evaluation team was responsible for overseeing all aspects of data collection and validation, as well as composition of the final report and recommendations.

All information from consultants was thoroughly reviewed by the Project Authority (EPMRB) and the Advisory Committee for quality, clarity and accuracy. Subsequently, the consulting firms thoroughly reviewed the analysis of data conducted by EPMRB to ensure their information was well-captured.

In addition, status updates and key findings were regularly provided to EPMRC for strategic advice and direction.

3. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

3.1 Continued Need

Is there an ongoing need for investment in First Nations Education programming?

Finding: There is a continued need to fund and otherwise provide resources to First Nation and Inuit students seeking post-secondary education based on a growing Aboriginal population, coupled with projected labour market needs, and the potential for improvements in First Nation and Inuit educational outcomes to contribute to meeting those needs.

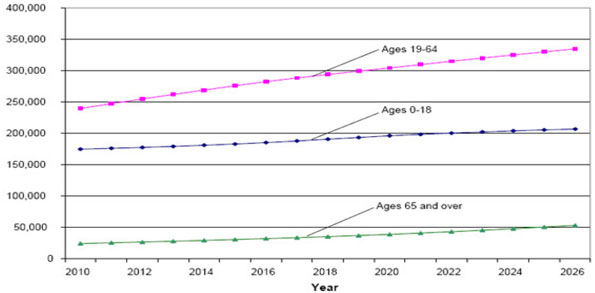

The need for continued investment in Education programming is amply demonstrated by the significant gap in educational opportunities and outcomes between First Nation and other Canadian learners.Footnote 11 Findings in the current study are consistent with observations made in the Formative Evaluation of PSE ProgrammingFootnote 12 - that the expected growth in the on-reserve population will undoubtedly generate greater needs for ongoing investment in First Nation education. Population projections obtained from Statistics Canada show a projected growth in the population of children on reserve of approximately 15 percent, or an additional 30,000 children (see Figure 1) over the next two decades. This does not include the potential implications of persons relocating to reserves as a result of amendments to Bill C-31.Footnote 13

Text description of Figure 1: Projected Population Growth by Age Category of Interest from 2010 to 2026

This figure is a graph indicating the projected population growth by age category each year during the period of 2010 to 2026. There are three age categories represented by independent lines: 0-18 years, 19-64 years, 65 years and over. The population rates are indicated on the 'y' axis and the years are indicated along the 'x' axis.

The 0-18 age category in 2010 is listed at approximately 175,000 and progresses to 200,000 by 2022. By 2026, the population rate for this age category reaches approximately 210,000.

The 19-64 age category had the most pronounced population growth. The 2010 rate began slightly below 250,000 and consistently progressed at a 30 degree trajectory, ending at just under 350,000 by 2026.

The 65 years of age and older category has a slow growth rate, beginning at approximately 25,000 in 2010 and progressing at a consistent rate, reaching 50,000 by 2026.

Historically, Aboriginal students in Canada have been under-represented in post-secondary institutions. The 2006 Census data reveals that 62.5 percent had no certificate, diploma or degree, 25.8 percent achieved a high school certificate or equivalent, 3.7 percent completed an apprenticeship or trades certificate or diploma, 5.5 percent achieved a college, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma, one percent had a university certificate or diploma below the bachelor level and, 1.5 percent completed a bachelors degree or higher.

Over the next decade, the Canadian labour market is anticipated to grow as a result of increased economic activity and an aging population that is entering its retirement years. A Human Resources and Skills Development Canada report, Looking-Ahead: A 10-Year Outlook for the Canadian Labour Market (2008-2017) indicates that between 2008-2017, about 5.5 million jobs are projected to open up due to an increase of economic activity and replacing existing workers - 67.2 percent of these openings will require post-secondary education.Footnote 14

In 2006, 25 percent of the working age Canadian Aboriginal population was 15-24 years old, nine percentage points higher than the non-Aboriginal population (16 percent).Footnote 15 Although the Aboriginal population will account for five percent of the total labour force for those between 15-64 years of age in 2026, it is important to note that the projected Aboriginal labour force in the same year will be much larger in certain provinces and more prevalent among the 15-29 age group.Footnote 16 For instance, those between the ages of 15-64 in 2026 will account for 28 percent of Saskatchewan's labour force, 22 percent in Manitoba, eight percent in Alberta,Footnote 17 and the proportion is larger with respect to the 15-29 year age group.

With respect to the national picture, there are two important observations. First, participation,Footnote 18 unemployment and employment rates for non-Aboriginals fared better than for the Aboriginal population for the 15-24 age group, including the Aboriginal population on reserve. Secondly, Canada's Inuit population did not do as well in all three accounts in comparison to the Métis, North American Indian and on-reserve populations. In particular, more than half of the Inuit labour force participants aged 15-24 were unemployed. With respect to the Aboriginal population living on reserve, half of labour force participants aged 15-24 (52 percent) were unemployed, which was higher than the total Aboriginal population (21.6 percent) unemployment rate against a participation rate of 51.9 percent.

Key informants, case study participants and survey respondents emphasized the role of post-secondary education programming as a means of enabling increased Aboriginal participation in the labour force. Key informants often spoke of the cost-benefit ratio of providing post-secondary education to Aboriginal peoples, highlighting that a robust program would enhance their overall capacity to compete in an increasingly globalized and knowledge driven economy. Moreover, some key informants drew attention to the potential for Aboriginal individuals with post-secondary accreditation to participate in Canada's economic development, particularly in the North.

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

Is the program consistent with government priorities and AANDC strategic objectives?

Finding: Education authority activities are generally aligned with Government of Canada priorities; however, recent major reforms are reflective of the need to better align activities and better ensure improvements in student success.

Insofar as Education Authority activities relate to better education outcomes for First Nation students, there is a clear strategic alignment with government priorities. The Government's continued investments and stated objectives for First Nations education – as outlined in budgets 2011Footnote 19 and 2012Footnote 20 – clearly demonstrate recognition of the need for strategic changes and innovative planning needed in order to better align AANDC activities with desired outcomes for First Nation and Inuit students.

Specific recent examples include the formation of the National Panel on First Nations Education; the introduction of a First Nations Education Act by 2014 and the Government's ongoing commitment as reinforced in the 2012 Budget to invest over $300 million per year supports First Nations and Inuit in their post-secondary studies through the PSSSP and the UCEP Program.

Major revisions in education-related activities reflect a common sentiment expressed by government interview participants in this study – that while AANDC education programming outcomes are aligned with the Government's objectives, its broad activities are undergoing significant reform because outcomes are not improving in a satisfactory manner.

In terms of increasing labour market participation, AANDC in 2007-08 began working in partnership with Saskatchewan First Nations, tribal councils, the Province of Saskatchewan, provincial employers, and training institutions to promote a range of active measures strategies focused broadly on First Nation labour market development through a Memorandum of Understanding. AANDC has invested more than $5 million in strategic pilot projects since 2007-2008 in Saskatchewan, including approximately $3 million in 2010-11.Footnote 21 This is part of an active measures approach that the Department is currently looking to implement across the country.

3.3 Role of the Federal Government

Is the current role of the Government of Canada legitimate, appropriate and necessary for the improvement of First Nations education success?

Finding: The roles and responsibilities of the federal government around post-secondary education remain unclear.

The federal government obtained its legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians" under Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary school services to Indian children living on reserves. Since the Constitution Act and the Indian Act do not make reference to post-secondary education, AANDC considers its involvement in Aboriginal post-secondary education as a matter of social policy rather than a legal responsibility.

There has been significant concern from oversight bodies such as the OAG and the Standing Committee on Public Accounts around AANDC's lack of clear roles and responsibilities surrounding Aboriginal education. They state specifically that "the Department must clarify and formalize its role and responsibilities, otherwise, its accountability for results is weakened and assurances that education funding is being spent in an appropriate fashion are unclear at best."Footnote 22

The majority of key informants did not discuss the role of the federal government, and aside from providing funding for post-secondary students they were unable to indicate any further involvement from the Department. Relationships between the Department and post-secondary institutions are essentially non-existent, though some argue that the Department has a role to play with regards to Aboriginal-controlled post-secondary institutions.Footnote 23.

4. Evaluation Findings – Performance

4.1 Achievement of Intended Outcomes

To what extent have intended outcomes been achieved as a result of AANDC programming?

Finding: There is evidence of some improvement in the achievement of outcomes for post-secondary with respect to interest in enrollment, and some indications of success. There is a strong need, however, for data collection improvements to allow for a reliable assessment of student enrollment and results.

In terms of overall improvement in post-secondary results, about 70 percent of survey respondents suggested that there has been at least some improvement over the past decade, while about 19 percent suggested there has been no change, and 11 percent suggested it has become worse.

It is possible that perceptions in post-secondary outcomes are heavily tied to the general well-being of the community. Whereas, successes in ESE can be immediately observed, successes in PSE may be much less readily evident as many of the students may never return to their communities for work. If the labour market is weak, then it is likely that successful post-secondary graduates will relocate.

In elaborating on improvements in outcomes over the past ten years, it is apparent that one key measure of success for participants is improving motivation and interest among students to pursue post-secondary. Particularly, participants noted that they have far more applicants, and there is gradually increasing emphasis socially on the necessity to pursue post-secondary studies. This positive attitudinal shift is tempered by more tangible outcomes, which participants largely indicated were limited because of inadequate preparation at the high school level. Many participants raised concerns about students being otherwise interested and motivated to pursue post-secondary studies, but lacking in numeracy and literacy essentials.

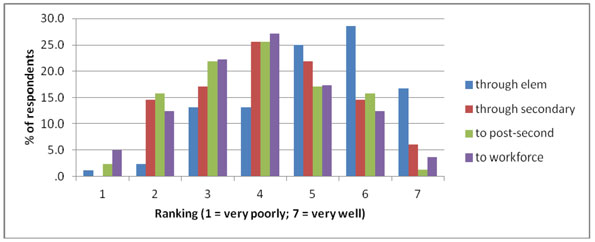

4.1.1 Progression

Survey participants saw strength in the ability of schools to equip students to progress through elementary school, but less so through high school, and much less so to post-secondary or into the labour market (see Figure 2). This was not attributed to the secondary schools being weaker than elementary; rather to the cumulative skills of students not being attained over time – with respondents suggesting more students are being "pushed ahead" than actually learning. The sentiment across interview, survey and case study participants was that students are not learning through elementary school and are, thus, at a serious disadvantage at the start of secondary, causing a cumulative impediment to progression and very low graduation success. These findings echo those of key informants.

Text description of Figure 2: Participants' Ranking of the Ability of Schools to Adequately Prepare Students

The participants' ranking of schools' ability to adequately prepare students is represented on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being very poor, and 7 being very well, represented on the x-axis. The percentage of respondents is represented along the y-axis. For schools' ability to prepare students to advance through elementary school, about 1% ranked '1'; 2% ranked '2'; 14% ranked '3'; 14% ranked '4'; 25% ranked '5'; 28% ranked '6'; and 17% ranked '7'. For schools' ability to prepare students to advance through secondary, 0% ranked '1'; 15% ranked '2'; 17% ranked '3'; 26% ranked '4'; 22% ranked '5'; 14% ranked '6'; and 6% ranked '7.' For schools' ability to prepare students to advance to post-secondary, 2% ranked '1'; 16% ranked '2'; 22% ranked '3'; 25% ranked '4'; 17% ranked '5'; 16% ranked '6'; and 1% ranked '7.' For schools' ability to prepare students to advance to the workforce, 5% ranked '1'; 13% ranked '2'; 23% ranked '3'; 27% ranked '4'; 17% ranked '5'; 13% ranked '6'; and 4% ranked '7.'

Among post-secondary students, only 30 percent felt that the schools in their community were strong in helping students progress from secondary to post-secondary, while 22 percent said they were acceptable and 40 percent said they were weak. They related this primarily to a lack of adequate academic preparation and a lack of culturally-relevant learning.

Similarly, when post-secondary students were asked whether secondary schools adequately prepare those not necessarily interested in post-secondary for the labour market, 39 percent said they were weak while 13 percent said they were acceptable, and 48 percent they were good or excellent.

When post-secondary students were asked how they felt they would fare in the labour market, the vast majority (78 percent) felt they would fare at least as well or better than their non-First Nation counterparts. Among these participants, however, there was a mix of fear of racism and a sentiment that in all probability, they would not be able to return to their First Nation because of a lack of job opportunities.

As for Inuit students, some interview and case study respondents say that the program has allowed Inuit youth to take part in the post-secondary schooling experience, and many have moved onto successful careers as a result. Even if students do not graduate from the program, they have had an opportunity to instill some of the skills required to ensure some level of success. The program allows for Inuit students to experience life in the South, and gain first-hand opportunities for positive life experiences.

4.1.2 Retention

The retention of Aboriginal students in post-secondary education institutions is an important facet of post-secondary education programming. Indeed, for post-secondary programming to be effective, students must not only enrol in educational institutions but must be retained in order to derive the full benefit of a post-secondary education.

Situated within the context of high drop-out rates at the post-secondary level, key informants have emphasized that each completed semester must be viewed as an important success. Additionally, the retention of students in post-secondary institutions has been identified as contributing to enhanced self-esteem and a greater sense of responsibility, as well as an opportunity for exposure to a new environment.

Post-secondary educational institutions are taking steps to facilitate student retention. The Nicola Valley Institute of Technology (NVIT), for example, has developed a Retention Alert Program, which allows faculty and concerned students to identify students who are in need of assistance, such as tutoring, counselling and financial support.

Furthermore, key informants have identified mentoring as a helpful component in student retention. The presence of a role model, particularly during the first six weeks of a student's attendance at a post-secondary institution, has been recognized as a significant mechanism for encouraging post-secondary student retention. Although data are not available to corroborate this finding, key informants have indicated that student retention is increasing.

4.1.3 Success

Post-secondary success is difficult to gage empirically, as student data are not recorded in the same fashion as elementary/secondary, and because only students funded through AANDC programming are tracked in its databases. Critically, in managing student information from one semester to the next, progression and graduation rates cannot be reliably calculated. The data contain all the students that had been accepted for funding for their post-secondary education as of November 1, and do not contain students that have not been accepted yet for funding, or who are enrolled in winter and/or summer sessions, even if they have been provisionally admitted to a program.

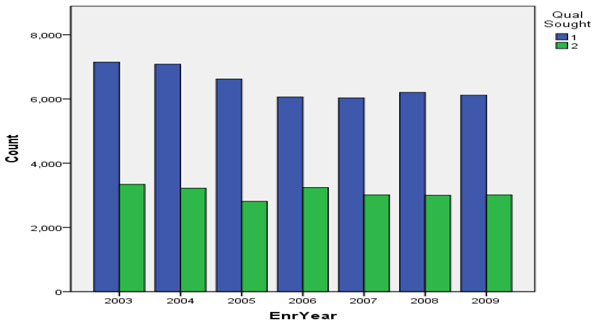

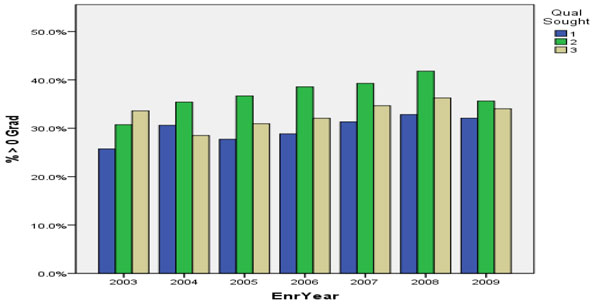

Among funded students, it can be surmised that the number of funded students enrolled in trades or college declined between 2003 and 2009, and remained relatively stable for students enrolled in university (see Figure 3).

Text description of Figure 3: Number of First Year (fall semester) Students Funded by Year, by Type of Program (1 = College/Trades; 2 = University)

The year of enrollment (2003 to 2009) is represented along the x-axis, and the types of program (college/trades versus university) are represented by separate bars within each year. The number of First Nation students funded in each type of program is represented along the y-axis. The bars representing college/trades is a little higher than 7,000 students per year, slowly declining over 2005 and 2006, and leveling off from 2006 onward at about 6,000 students per year up to 2009. The bar representing university enrollment is somewhat steady across the seven years roughly between 3,000 and 3,500 students per year.

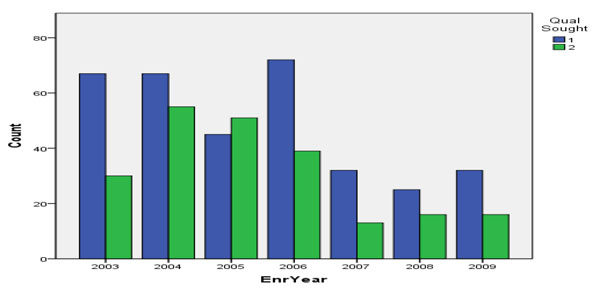

Importantly, the number of Inuit students funded and enrolled had been declining sharply between 2003 and 2009 (see Figure 4).

The graduation rate cannot be calculated in the purest sense – that is, the proportion of students who begin post-secondary who ultimately graduate. However, it was possible to examine the proportion of enrolled students who were in their final year of their program, or past their final year (for example a student in a 4-year degree program who was in their fourth year or higher), who were logged as having graduated. As shown in Figure 5, there have been some improvements and the proportional increase has been significantFootnote 24 over time. The most considerable improvements were noted in Atlantic region, Ontario and Manitoba.

First year enrollment in program types was steady over time; except Native studies, which has decreased at the college level and increased at the university level; and health sciences, which has increased at the college/trades level.

Text description of Figure 4: Number of Inuit First Year (fall semester) Students Funded by Year, by Type of Program (1 = College/Trades; 2 = University)

The enrollment year (2003 to 2009) is represented along the x-axis, with the type of program (college/trades versus university) represented by two separate bars within each year. The number of Inuit students funded per year is represented along the y-axis. For students funded for college/trades, there are 67 in 2003; 68 in 2004; 45 in 2005; 71 in 2006; 35 in 2007; 27 in 2008 and 37 in 2009. For students funded for university, there are 29 in 2003; 55 in 2004; 51 in 2005; 39 in 2006; 15 in 2007; and 17 in 2008 and 2009.

Text description of Figure 5: Proportion of Students in their final year or beyond their final year who are logged as having graduated, over time, and by Qualification Sought (1 = College/Trade; 2 = Undergraduate Degree; 3 = Graduate Degree)

The enrollment year (2003 to 2009) is represented along the x-axis, with type of qualification (college/trade certificate, undergraduate degree, and graduate degree) represented by three different bars within each year. The percentage of those in, or past, their final year, and having been logged as graduated, is represented along the y-axis. For those seeking a college/trade certificate, the percentage in 2003 is about 26% and slowly increases over time to about 30% in 2009. For those seeking a university degree, the percentage in 2003 is about 30% and slowly increases over time to about 40% in 2008, but shows a decrease to about 35% in 2009. For those seeking a graduate degree, the percentage in 2003 is about 34%, and this decreases to less than 30% in 2004, and slowly increases up to 35% in 2008 and 33% in 2009.

4.2 Program Influence on Collaborative Engagement and Networks

To what extent has the program influenced constructive engagement and collaborative networks to facilitate education and skills development?

Finding: There is evidence to suggest that community-based programming is occurring and providing positive results for students and communities.

Increasingly, post-secondary access and retention initiatives are being delivered in Aboriginal communities. Community-based education initiatives enable students to complete a diploma or degree program without leaving their community. Examples of community-based education initiatives include partnerships between municipal agencies and educational institutions,Footnote 25 distance learning programsFootnote 26 and tribal controlled post-secondary institutions. In some cases, satellite campus models have proven to be effective.Footnote 27

One example of a tribal college partnership exists between Simon Fraser University (SFU) and Aboriginal-run NVIT. These institutions formed a partnership whereby Aboriginal students with some post-secondary education are given access to several years of work experience and the opportunity to attain a Bachelor's Degree in General Studies. SFU and NVIT worked together to develop similar degree accreditation programs, namely the Aboriginal Community Economic Development Program (ACED) and a Business studies option offered to the Interior Salish people.

Although the ACED program experienced a declining graduation rate, with 80 percent graduating in 2004 and 56 percent in 2006, most graduates elected to work as Economic Development Officers in their communities. A number of institutional differences between SFU and NVIT emerged and the ACED program has been discontinued. Nevertheless, Price & BurtchFootnote 28 have identified the ACED example as an opportunity to explore the complexity of collaborative partnerships in the field of Aboriginal education.

Another example of a positive community-based program initiative is the First Nations Partnership Program (FNPP), a generative curriculum modelFootnote 29 that was developed in response to a request from a group of First Nation communities in central Canada to provide community-based child care training, which both reflected and maintained the cultural practices, values, language, and spirituality of the local population. Through the FNPP, indigenous educational expertise, particularly the knowledge of community Elders, is incorporated into the teaching and learning processes of First Nation students. Furthermore, the generative curriculum model exposes Aboriginal students to Euro-western curricula and encourages discussion regarding the similarities and differences of the two approaches within historical, cultural, political and personal contexts.

In addition to positive retention outcomes, the FNPP has been identified as a mechanism for strengthening community capacity, revitalizing intergenerational teaching and learning roles and advancing First Nations' social development goals.Footnote 30

Bearing in mind that many community-based initiatives are new, data relating to their efficacy is limited. Nevertheless, community-based initiatives have been identified as useful mechanisms for alleviating considerable historical, institutional, geographic and financial barriers to Aboriginal post-secondary education.Footnote 31

4.3 Factors Facilitating or Hindering Achievement of Outcomes

What factors have facilitated or hindered the achievement of outcomes?

Finding: The most common challenges facing First Nation students include academic readiness for post-secondary studies, access to finances for tuition and other costs, and a difficult transition period. Evidence further suggests the critical importance of family and community support, and the benefits of culturally-relevant curricula and transitional support from institutions.

4.3.1 Readiness for Post-secondary Studies

Survey, interview and case study participants overwhelmingly suggest that schools are not adequately preparing students to be eligible or ready for post-secondary studies. In some cases, students make significant strides to graduate from high school only to realise that they lack the prerequisite course work and/or grades to qualify for their program of choice. In such cases, the degree of "upgrading" that would be required often deters otherwise interested students from pursuing their career goals. In other cases, there is simply a lack of study skills even when students complete high school, and students often become overwhelmed by the degree of prerequisite knowledge assumed at the beginning of courses, as well as the degree of studying required. Many participants raised concerns about students being otherwise interested and motivated to pursue post-secondary studies, but lacking in numeracy and literacy essentials.

Beyond academics, many First Nation participants felt that students are often not equipped with the necessary life skills to live independently, which can act as a major impediment to focussing on studies. Moreover, many survey respondents expressed concern that a lack of education in their home community was a key barrier to post-secondary readiness because expectations of what is needed for academic success are not well understood. Respondents suggested that the result was often a lack of adequate encouragement from parents and peers, the idea of leaving behind peer groups, a fear of failure, and discomfort of being away from family and peer supports.

Participants suggested that one key measure of success for participants is improving motivation and interest among students to pursue post-secondary. Particularly, they noted that they have far more applicants, and there is gradually increasing emphasis socially on the necessity to pursue post-secondary studies. This positive attitudinal shift is tempered by more tangible outcomes, which participants largely indicated were diminished because of inadequate preparation at the high school level.

4.3.2 Access to Post-secondary Opportunities

By far, the most pervasive issue raised was insufficient funds to accommodate all qualified applicants. This was raised by respondents across the board with respect to increasing numbers of students wanting to attend post-secondary (both at the undergraduate and graduate levels); a sharply increasing population of university-aged people; coupled with marginal to no increases in available funding. In fact, most First Nation respondents responsible for post-secondary services indicated they have a wait list for post-secondary funding. Many communities and tribal councils have attempted to obtain funds from other sources to either increase the numbers funded, or increase the amounts given to those funded, although most indicated this was very difficult or impossible, and was only viable among communities with strong mutual networks or strong economies.

Some did suggest that technically, there are equal opportunities once children go to provincial schools and post-secondary education. The difference is that in order to be able to take advantage of those opportunities, a First Nations child has to work harder and "overcome the odds" to achieve the same outcome that would be typical for non-First Nations children.

In order to assist potential students in readying themselves for post-secondary education, access or "bridging" programs can assist those who typically do not meet institutional entrance requirements, including those who have not graduated from high school, to access, persist, and graduate from accredited post-secondary programs. Access programs are based on the tenet of equality of condition, which proposes that students who are motivated, but poorly prepared and under-resourced have a realistic opportunity to succeed in PSE if they are granted access and provided with appropriate supports.Footnote 32

While little documentation could be found on access programs, between 2004 and 2009, it was found that approximately 33 percent to 38 percent of UCEP students enroll in accreditation-level post-secondary studies the following year. Consistently, about 2/3 of those who enter post-secondary studies from UCEP go into college/trades, and about 1/3 to university.

4.3.3 Transition Challenges

Cost of living was the most pervasive issue raised in terms of transition to post-secondary, with 74 percent of student respondents identifying it as a significant challenge. Most participants who discussed this issue suggested that a living allowance is almost completely decimated by rent costs alone. To add to this, parents are rarely in a position to help financially. The limited availability of funds was said to cause stress and distraction from studies. Many First Nation participants noted that funds for living allowances have remained static despite massive increases in inflation, especially in larger cities.

Also pervasive was the issue of adjusting to a new environment. Most respondents indicated students struggle to adjust to city life, mass transit, apartment or residence living, etc. The majority of students said that finding a suitable residence is a challenge. There was a sentiment that many students feel disoriented and alone, often caused by the transition from a more collectivist to individualist culture and the resulting culture shock, which can significantly impede the focus on studies. Many believe this is a major contributor to drop-out, though some suggest that more consistent, well-funded specific First Nations counseling throughout the high school years, preferably on reserve, is key to helping students through this transition. Others suggest that bringing branches of local community colleges either closer to the reserves, or even onto reserves, would have a positive impact on both enrollment rates and graduation rates from these institutions.

Further, while child care considerations can act as a deterrent to pursuing post-secondary altogether, it can also be a serious issue for those eligible and willing to pursue it. Overwhelmingly, participants felt that living allowances for student parents were inadequate to cover actual day care costs, especially in larger centres. Additionally, and consistent with trends across Canada, there are significant issues with availability of child care generally.

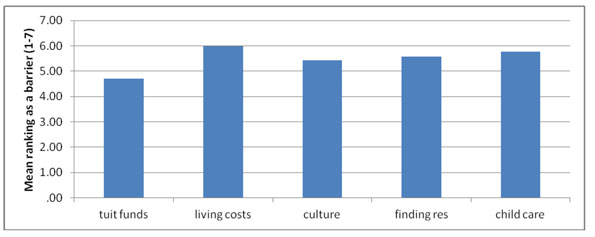

As shown in Figure 6, all of these barriers on average were seen as impediments roughly equally. It should be noted though, that similar to the post-secondary students themselves, affordability of living costs was seen as the most pervasive issue by education administrators in terms of the frequency of it being ranked as a significant barrier compared to the other barriers.

Text description of Figure 6: Mean Degree of Barrier (from 1 being not a barrier to 7 being a significant barrier) Faced by Post-secondary Students

Each identified barrier is named along the x-axis. Its average ranking as a barrier on a scale of 1 to 7 is represented along the y-axis. Tuition funds is ranked around 4.7; living costs is ranked around 6; culture is ranked around 5.3; finding a residence is ranked around 5.6; and child care is ranked around 5.8.

4.3.4 The Importance of Family and Community

The importance that parents and communities place on education is considered a significant factor in student success rates. Three of the most prevalent challenges identified by Aboriginal students in their transition to post-secondary education are related to family and community: family pressure to stay home, family conflicts, and feeling disconnected from home and culture. It is clear that considerations pertaining to family and community are important factors in the post-secondary experience of Aboriginal students. Moreover, family and community have been shown to have a significant influence on student success.Footnote 33

The importance of family and community support is further highlighted in noting that students who had the support of both parents and/or had a family member who had completed a post-secondary education program were more likely to report a more positive transition to post-secondary education. Nevertheless, family and community support can also be a source of conflicting messages, with students feeling simultaneously pressured to leave their communities to attain a post-secondary education and to maintain their traditional tribal connections.Footnote 34

The case studies reveal that some institutions, such as University of Victoria and NVIT, encourage families to come to celebrations, and host family events that are relatively well-attended. While there are sometimes issues with travel and displacement, as many Aboriginal students come from far away, it is important for institutions to realize that family is often a core value for Aboriginal students who seek to build their education around a family life.

In British Columbia, communities are often eager to work with PSE students in a reciprocal relationship in order to meet dual needs. It must be noted, however, that it takes time to build community relationships and support, and that year to year funding makes these relationships hard to maintain. Other provinces, such as Ontario in recent years, have funded Aboriginal post-secondary institutions under multi-year agreements, and this reportedly has already improved First Nation student outcomes and graduation rates.

4.3.5 Cultural Curricula and Support

The infusion of Aboriginal culture into academic learning has been identified as a significant factor in the achievement of educational outcomes.Footnote 35 Research conducted by the University of Victoria revealed that Aboriginal students perform better when culturally relevant images, such as Aboriginal artwork, are present in the learning environment. Additionally, Elders are seen as critical to student success. Key informant interviews emphasized the importance of Elders, indicating that Elders assist faculty members in providing valuable input for research as well as provide guidance to students.

The University of Victoria, for example, has noted an increase in the number of students benefitting from the opportunity to consult with Elders. Nevertheless, some key informant interviews have highlighted that post-secondary institutions neglect to consider certain forms of learning, such as visual and oral memory, when designing exams at the academic level.

4.3.6 Unintended Outcomes

A variety of unintended outcomes results from post-secondary education programming. For many Aboriginal students, the transition to the post-secondary level poses considerable challenges. Larger class sizes, increased homework volume and an atmosphere of academic competition tend to have a demoralizing effect on Aboriginal students. Programs offering counselling, academic assistance and mentoring have been implemented in an attempt to ease the transition process.

Financial concerns continue to impede student success and various mechanisms, in the form of emergency loans and bursaries, have been established by some post-secondary institutions. Furthermore, post-secondary institutions provide a host of ongoing services, such as Aboriginal culture training for staff members, the creation of social spaces, tours of the campus, film events, and craft fairs, to foster an educational environment, which both attracts and retains Aboriginal students.

Some post-secondary institutions have introduced child-care facilities and food programs to meet the needs of Aboriginal students. Additionally, in an effort to address the housing challenge, which is particularly acute for adult learners with families, some post-secondary institutions are devoting resources to the construction of student residences, which are equipped to house families.

4.4 Design and Delivery

To what extent has the design and delivery of the program facilitated the achievement of outcomes and its overall effectiveness?

Finding: The current approach to funding post-secondary students is problematic in that it does not allocate funding based on need, and there is little accountability for the degree to which post-secondary funds are used to fund students.

The design and delivery of post-secondary education planning emerged as a prominent topic of discussion in key informant interviews, with the FNSSP being identified as the most common positive element. Nevertheless, the participants were unable to specify any particular strengths of the program apart from noting that it provides some funding to Aboriginal students. Furthermore, when asked to identify the challenges facing post-secondary education, the vast majority of respondents pointed to issues surrounding funding, particularly, the shortage of available funds to provide access to post-secondary education for all qualified applicants and the insufficiency of existing funds to continue to support current students.

Most First Nations bands manage their own post-secondary funding. Tuition rates and living allowances are based on individual band policies. Case studies revealed that these can play a pivotal role in the extent to which bands support students needs, and when they do not, students may have to drop out with a debt to pay back to the band.

In 2011, the OAG released an update on their recent findings for First Nation programming, which found that AANDC has not explicitly reviewed its post-secondary funding mechanisms despite reviewing some delivery options. In line with key respondents, the report further noted that AANDC allocates its funds to communities without regard for the number of eligible students, and that band governments have the flexibility to allocate the funds for purposes other than education. Overall, the report found that "the current funding mechanism and delivery model used to fund post-secondary education does not ensure that eligible students have equitable access to post-secondary education funding."Footnote 36

Furthermore, key informant and survey respondents frequently reported AANDC's funding cycle as being problematic. Many respondents emphasised that long-term initiatives—particularly, planning and leadership-building projects—cannot be embarked upon when levels of funding fluctuate on an annual basis.

The inclusion of cultural elements, such as the incorporation of community Elders into post-secondary education programming continues to be a challenge, despite some efforts to introduce these elements. Key informants indicated that Elders are not regularly compensated—in the form of honoraria and travel cost reimbursements—for their contributions to enhancing the post-secondary educational experience of Aboriginal students. Moreover, participants emphasized that greater efforts need to be made to incorporate the traditional knowledge of Elders into the design and delivery of post-secondary education programming.

5. Evaluation Findings – Efficiency and Economy

Is the current approach to programming the most economic and efficient means of achieving the intended objectives?

Finding: The current approach to programming may not be the most efficient and economic means of achieving the intended objectives of PSE programming.