Archived - Impact Evaluation of Contributions to Indian Bands for Land Management on Reserve

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: September 2010

Project Number: 09068

PDF Version (479 Kb, 87 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Commonly Used Terms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response/Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Context: Understanding Land Management

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Additions to Reserve

- 5. Evaluation Findings: Land Management Programs under the Indian Act

- 6. Conclusions

- 7. Recommendations

- Annex A: Summary of Interviews

List of Acronyms

| 53/60 | Delegated Lands Management Program |

|---|---|

| AFN | Assembly of First Nations |

| ATR | Additions to Reserve |

| CESP | Community Environmental Sustainability Plans |

| DG | Director General |

| DoJ | Department of Justice |

| EPMRB | Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| EPMRC | Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee |

| ESA | Environmental Site Assessment |

| FN | First Nations |

| FNLMA | First Nations Land Management Act |

| HQ | Headquarters |

| ILRS | Indian Land Registry System |

| INAC | Indian and Northern Affairs Canada |

| LED | Lands and Economic Development Sector (INAC) |

| NALMA | National Aboriginal Lands Managers Association |

| NATS | National ATR Tracking System |

| NEDG | New Economy Development Group (New Economy Group) |

| NRCan | Natural Resources Canada |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| RLAP | Regional Lands Administration Program |

| RLEMP | Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program |

| SCB | Specific Claims Branch (INAC) |

| TLE | Treaty Land Entitlement |

Commonly Used Terms

Buckshee leasing/customary land management practices and allocations. These land tenure arrangements take many forms from unwritten agreements to a sophisticated lease with clear roles and responsibilities for each party. Unlike legal interests, the courts do not recognize these arrangements.

Creation of legal interests. This term refers to the creation of legally-recognized tenure agreements both among band members and non-member parties. A number of tenure instruments are available under the Indian Act, including leases, permits, easements, designations and surrenders. The alternative to this system of tenure allocation under the Indian Act are customary land management practices and buckshee leases.

Fiduciary duty. The Crown's fiduciary duties to First Nations are premised on the fact that the federal government holds Indian lands in trust for the use and benefit of individual bands. The relationship and scope of these duties have been defined by and are subject to legal interpretation. Guerin v. R. (1984) is landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision both generally to the understanding of the Crown's fiduciary duties and in the specific land management context of this evaluation. Other case law has followed this case, which has further extended the scope and clarified certain aspects of the fiduciary relationship Canada shares with Aboriginal peoples.Footnote 1

Indian Lands Registry System. The Indian Lands Registry System (ILRS) is a database containing instruments relating to transactions on reserve lands. The system permits the generation of inquiries and reports by First Nation reserve.

Land management /administration. One author describes land management as the process of both decision-making and implementing the decisions about land. Footnote 2 Land management systems are the means by which policies related to the management and control of land tenure systems are implemented. These might include minimizing land disputes, facilitating orderly settlement and regulating the sustainable use of land and resources. Following a recent report prepared for the Lands Branch, land management is used in this report to refer to the economic, social and environmental uses of land, including land and environmental planning and stewardship.Footnote 3

Land administration is the means by which land and resource management is implemented or facilitated.Footnote 4 Activities include surveying and mapping of land parcels, land conveyance, taxation, creation and allocation of interests in land and land registration. Generally, the report uses the Land administration is mostly used in this paper to identify INAC's statutory obligations to First Nations under the Indian Act.Footnote 5

Land Surveys. Though this term has a number of uses, this evaluation primarily discusses land surveying as the process of locating and measuring property lines, both within an Indian reserve and to define its boundaries.

Performance measurement strategy. Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation and related directive require all programs to have a performance measurement strategy in place at the time of program design (Treasury Board submission stage). Performance measurement strategies describe program logic, outline key indicators of outputs and outcomes and develop a strategy for collecting program data, including targets, timelines, responsibilities and methods.

Statutory obligations. This term relates to INAC's land administration responsibilities under the Indian Act and Canada Lands Surveys Act.

Survey fabric. This term is used to refer to the extent of coverage and quality of land surveys on reserve. A strong survey fabric is one in which the boundaries of the reserve and internal allotments are well-defined. This leads to greater certainty of possession, facilitates land use planning and removes impediments to economic development.

Transaction costs. The term transaction cost has its roots in economic theory where it describes any cost incurred through an economic exchange. This term is used in this report to refer to a variety of costs associated with land transfer, including research and identification costs, time and human resources costs associated with negotiating and bargaining and monetary acquisition costs.

Executive Summary

Introduction

The evaluation examines certain activities under the Treasury Board authority Contributions to Indian Bands for Land and Estates Management for the period covering 2005/2006 to 2009/2010. The goal of the evaluation is to study the performance of the land management system as a whole, including the extent to which First Nations have access to land.

Two key program areas are included in this evaluation: Additions to Reserve (ATR) and the Indian Act Land Management Programs, Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program (RLEMP), Regional Land Administration Program (RLAP) and 53/60 Delegated Authority Program. The evaluation also considers a number of cross-cutting activities and systems supporting land management, including land surveys, the Indian Land Registry System, creation of legal interests and other related activities that are important to supporting ATRs and land management on reserve. Environmental issues are considered as part of the RLEMP, namely as they apply to First Nation funding for land use planning and environment management.

Total expenditures under the Contribution Authority for the activities being evaluated were $46.3 million for the five-year period from 2005/2006 to 2009/2010. The scope of the evaluation includes an additional estimated $76 million in direct program spending associated with supporting First Nation land managers and Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) land management on behalf of First Nations not involved in the capacity-building and devolution programs. This renders an evaluation scope covering a total of $122.4 million in program spending.

Methodology

Structure

The evaluation is structured around the five core evaluation issues as outlined in the 2009 Treasury Board Secretariat Evaluation Policy and Directive: continued need for program; alignment with government priorities; alignment with federal roles and responsibilities; achievement of expected outcomes; and demonstration of efficiency and economy.

Lines of inquiry

The evaluation made use of a number of methodologies to fully examine the many activities under analysis.

- An Elders Roundtable Discussion provided an essential understanding of the special relationship Aboriginal people share with the land.

- A Historical-Legal Review analyzed applicable statutes, regulations and decisions of the courts to provide an understanding of land management under the Indian Act and incorporated interviews with Department of Justice officials to provide perspectives on INAC's fiduciary obligation to First Nations in an increasingly complex environment.

- A Document and Literature Review provided evidence for the rationale of the programs, their alignment with government priorities and other evaluation issues.

- Key Informant Interviews with a number of representatives from First Nations, INAC (regions and Headquarters (HQ) and other stakeholders contributed to a multi-faceted understanding of how the programs are working and the extent to which they are achieving results.

- Case studies targeted important issues in modern-day land management, including integrated land use planning, land survey fabric, customary land allocations, capacity-building at the community-level and co-operation among ATR stakeholders.

- The Financial and Performance review, though limited in its application, enabled analysis of trends over time and provided an understanding of how departmental A-base and contribution funding support land management and land conversion.

Quality control

A Working Group consisting of program managers, and including regional representation, was established to review and verify documents throughout the evaluation process, including the methodology, preliminary findings and draft report. Quality control was further ensured through advice and support from an Aboriginal Advisory Committee.

Summary of findings

The following findings are organized based on the evaluation issues and questions outlined in the evaluation Terms of Reference.

Relevance

1) To what extent do the programs under evaluation address a demonstrable need?

All programs under analysis clearly address a demonstrable need. Increasing the reserve land base is necessary and significant to First Nations. The Additions to Reserve Program aims to correct historical inaccuracies, increase economic opportunities and help to sustain a growing on-reserve population.

First Nations require the resources, flexibility and expertise to respond to land management demands and take advantage of economic opportunities. INAC's land management services and capacity-building programs are intended to support modern land management to the greatest extent possible under the Indian Act.

2) To what extent are the programs responsive to the needs of Aboriginal people?

Though the programs target issues of great need in First Nations communities, they are not completely responsive to these needs. The ATR process is slow, cumbersome and focuses almost entirely on Canada's legal obligations to First Nations.

The RLEMP is responsive to the needs of some First Nations, namely those that have a high capacity in land management and are already involved in RLAP and 53/60. Entry requirements into the newly redesigned RLEMP program are still restrictive. Financial and human resources limit the extent to which INAC land administration services are responsive to First Nation needs.

3) To what extent are the programs aligned with Government of Canada priorities?

The evaluation found that the programs under evaluation are in line with Government of Canada priorities, specifically those related to engaging Aboriginal people in the Canadian economy, building capacity and self-reliance, and fulfilling Canada's treaty obligations. However, there is evidence that improvements could be made to the design of the ATR program to better enable it to achieve efficiency priorities.

4) To what extent are the programs aligned with INAC strategic outcomes and priorities?

The programs under evaluation are integral to achieving INAC's Strategic Outcome of the Land to enable First Nations to benefit from their land, resources and environment on a sustainable basis. The programs are aligned with INAC priorities of increasing social and economic well-being of First Nation communities, encouraging investment and promoting development.

5) Is there a legitimate and necessary role for INAC and the Government of Canada in the activities under evaluation?

Canada has the obligation to address legitimate claims. Most of the ATRs that were processed during the evaluation period fell under the Legal Obligations category of the ATR policy. INAC's land administration program fulfils statutory obligations under the Indian Act.

Design & Delivery

6) To what extent does the design of the programs contribute to outputs and outcomes?

Communication and collaboration regarding ATRs are weak, both within INAC (between HQ and regions, across the Lands and Economic Development (LED) sector, with the Specific Claims Branch) and with stakeholders and partners outside the Department. While program design satisfies the ATR policy, the policy itself impedes efficiency and the achievement of outcomes through cumbersome process requirements. As such, discussion is underway with the Assembly of First Nations to streamline the ATR process and achieve more timely results.

The current design of RLEMP excludes First Nations that do not already have some land management capacity. The curriculum of the program could be expanded to better meet First Nations' needs through a greater emphasis on environmental training. More generally, the evaluation found legislative and regulatory design flaws with land administration under the Indian Act. As a simple repository for lands transactions, the design of the Indian Lands Registry system is not aligned with the need for a reliable registry that secures land tenure through guarantee to title.

7) To what extent have programs been implemented as planned?

- Understanding of roles and responsibilities

In addition to differences across provincial jurisdictions, roles and responsibilities are unclear and not well-understood. A lack of tools is resulting in the inconsistent delivery of policies, procedures and guidance. - Alignment of delivery with design

There has been mixed success in the alignment of program delivery with program design. Resource pressures, including staff turnover, limited organizational knowledge, low classifications and budgetary constraints are restraining the ability of programs to be delivered as planned.

8) To what extent are performance data, reporting and accountability systems in place and contributing to success?

Limitations and gaps in the performance and accountability systems make it difficult to fully assess success. Nevertheless, new performance measurement and reporting systems for both the RLEMP and ATR programs have been developed and are now being implemented.

Performance (effectiveness)

9) To what extent is the program achieving progress toward outcomes, including:

Immediate outcomes

Some of the immediate outcomes related to the ATR program have been achieved. Reserves are being created and expanded across the country. However, many of these new reserves are being created under the Treaty Land Entitlement process as Canada's legal obligations take precedence over other ATR policy categories. While the Crown's legal and policy obligations for the transfer of title are being met, a slow and cumbersome process based on an inefficient policy is impeding success. As well, there has been mixed success in the engagement of stakeholders, further slowing the ATR process. Special ATR legislation in the Prairie provinces was found to increase the effectiveness of the process.

The capacity-building/devolution programs, namely RLEMP, are increasing knowledge and skills and enabling First Nations to assume greater control over land management. Where possible, through its land administration services, INAC provides technical and advisory support upon request to all First Nations (including those outside the RLEMP program). However, land management on reserve is becoming increasingly complex due to land use planning and environmental standards and highly specialized commercial leasing projects. The level of human and financial resources available, including expertise and knowledge is presenting significant challenges in this regard. With an average backlog of 67 percent in survey needs requested versus survey needs met, INAC's land survey program does not adequately support land management.

In addition, at present, only eight percent of the total First Nations in the RLEMP, RLAP and 53/60 programs are managing their lands under delegated status. In total, 27 percent are either operational or fully administering their land. All others in these programs are involved only at the training and development levels or are performing land administration services alongside regional INAC land managers.

Intermediate outcomes

Without data concerning the requests by ATR policy category and the timeline between ATR request received and ATR completion, the evaluation is not able to properly assess the extent to which the program is increasing access to land that meets First Nations communities' interests and needs.

Few First Nations have the ability to fully manage land and environment to meet their communities' needs as a result of the capacity building/devolution programs. Some First Nations land managers either do not have the opportunity to use knowledge and skills to perform a complete set of land management activities, or cannot perform these activities. However, the evaluation found that First Nations in the RLEMP, RLAP and 53/60 programs are involved in a range of land administration activities.

Long-term outcome

Given the prospect of resource development or urban location, there is the potential to increase economic development opportunities through ATRs. When available in 2011, data from the Community Well-being Index will allow for a comparison with 2006 data to better assess whether First Nations are benefiting from the lands programs. Analysis has shown, however, that there is a positive relationship between the Community Well-being Index and internal survey fabric.

It is difficult to establish attribution between the programs and the long-term outcome of increased quality of life and self-reliance. The limited number of First Nations operating under the RLEMP, RLAP and 53/60 programs, and the fact that RLEMP has just recently emerged from pilot status, suggest that more time is required before there is indication of progress toward this outcome.

Performance (efficiency and economy)

10) To what extent have the programs been delivered efficiently? How could efficiency be improved?

The evaluation found that efficiency could be improved by streamlining the ATR policy and process, which may require legislative and regulatory change. Greater capacity among INAC officials, First Nations and others involved in the ATR process may also help to increase efficiency.

The RLEMP program is achieving results; however, the efficiency of the program could be increased by expanding the role of the National Aboriginal Land Managers Association (NALMA). More generally, a lack of legislative frameworks, policies and tools that meet the needs of a modern land management regime is inhibiting efficiency. Communication and collaboration between the LED units of INAC are not maximized.

INAC's funding to Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) for survey services inhibits efficiency. Reliance on departmental operational funding late in the fiscal year makes it difficult for NRCan to properly plan for and implement surveys.

11) Are the programs cost-effective? How could cost-effectiveness be improved?

Given approximately 68 percent of all First Nations in Canada are not engaged in INAC's land management capacity building/devolution programs or are conducting land management activities outside of the Indian Act points to two key findings related to cost-effectiveness. First, long term support from INAC is necessary to address the needs of those First Nations requiring assistance to perform their land management responsibilities. As such, the RLEMP program alone and as it is currently structured is not likely to achieve cost-effectiveness. Second, the fact that many of these First Nations choose to conduct land administration outside of the Indian Act suggests that the current land management regime under the Indian Act is not effective and does not meet their needs. In addition, INAC still plays a significant role in providing land management services to First Nations under RLEMP, suggesting that the program has not yet resulted in cost-effectiveness.

The evaluation found some evidence that fee-simple ownership of land may be a viable alternative to ATRs to achieve economic development. Fee-simple land holdings present far fewer challenges and transaction costs; however, it is also important to note that fee simple land remains under a provincial regime, which prevents First Nations governance over the land. Fee-simple land holdings do not offer the tax benefits associated with ATRs and impose further municipal tax requirements on First Nations.

Recommendations

It is recommended that INAC:

1) Continue to work towards / consider legislative change in the following areas:

- national ATR legislation that incorporates process and approval improvements to streamline the process and increase efficiency;

- legislative alternatives to the current designation process, which is cumbersome, unresponsive and sets a standard that has no off-reserve equivalent;

- recognition of some forms of modern land tenure arrangements outside of the Indian Act. and

- legislative and regulatory base for a modern land registry with possible interim arrangements with provincial land registries.

2) Examine the feasibility of broadening the reach and accessibility of the ATR and RLEMP programs through:

- providing for the implementation of a greater number of ATRs from policy categories other than legal obligations; and

- extending RLEMP access to First Nations of varying land management capacities, taking into consideration INAC's Capacity Development Policy being proposed.

3) Increase internal capacity and effectiveness of INAC land management services through the development of clear roles and responsibilities both within LED and among stakeholders and delivery partners, appropriate classification levels, training, tools and incentives to decrease turnover.

4)

- Encourage joint/multiple collaboration between First Nations with limited capacity, including continued support to Aboriginal organizations (e.g. NALMA and tribal councils) that support and enable capacity-building among First Nations.

- Promote greater coordination and integration between economic development and land management functions and other INAC programs such as Capital Infrastructure.

5) Improve financial data and monitor the implementation of the ATR and RLEMP performance measurement strategies.

Management Response/Action Plan

Impact Evaluation of Contributions to Indian Bands for Land Management on Reserve

Project #: 1570-07/09068

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) a) Continue to work towards:

b) Consider legislative change in the following areas:

|

LED is continuing an engagement process with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) on Additions to Reserve (ATR) and associated land management issues in accordance with the November 2007 Political Agreement signed by Minister Strahl and the National Chief. The joint agenda includes determining the possibility of proposing national legislation. These discussions will include the possibility of expanding any legislative proposal to deal with the areas raised by the evaluators, and more specifically to provide an optional alternative to some of the Indian Act land management tools. Any new tools would be focussed on supporting First Nations in economic and community development and address the impediments to effective land management that exist in the Indian Act. | DG, Lands and Environment | On-going/ dependent on the engagement process |

| 2) Examine the feasibility of broadening the reach and accessibility of the ATR and RLEMP programs through: | |||

| a) Providing for the implementation of a greater number of ATRs from policy categories other than legal obligations. | a) As noted above, LED is continuing an engagement process with the AFN on ATR. The joint agenda includes a renovation of the ATR policy and process, which includes a review of the policy categories and how they are prioritized, and will focus on the efficiency and effectiveness of the process. The parties have noted that the current policy is not supportive of ATRs undertaken for economic development purposes in situations where the ATRs are not also Legal Obligations or Community Additions. | DG, Lands and Environment | On-going |

| b) Extending RLEMP access to First Nations of varying land management capacities, taking into consideration INAC's Capacity Development Policy being proposed. | b) Additional funds for the land management programs were secured through the Aboriginal Economic Development Action Plan. INAC is presently in the process of renovating the current programs in an effort to identify more efficient mechanisms to meet First Nations' requirements related to land management capacity. | DG, Community Opportunities | On-going |

| 3) Increase internal capacity and effectiveness of INAC land management services through the development of clear roles and responsibilities both within LED and among stakeholders and delivery partners, appropriate classification levels, training, tools and incentives to decrease turnover. | LED, in consultation with regions and stakeholders, will develop communications strategies and related products. An example of this is that LED partnered with the National Aboriginal Lands Managers Association (NALMA) to produce an ATR Manual for First Nations. The manual, which will be rolled out by NALMA at its October 2010 National Meeting, clarifies the roles and responsibilities of First Nations, the department and other parties in the ATR process. LED has also partnered with the Office of the Surveyor General of Canada, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) to work with five First Nations across the country to address the survey and parcel fabric on-reserve, which is typically of a much lower quality than off-reserve and results in numerous boundary and other disputes. The objective is to develop tools and systems that will be used to assist a wider range of First Nations with survey and boundary issues. Discussions are also underway with NALMA on the possibility of providing land management training to LED staff across the country. Additional opportunities for such joint work will be explored with AFN, NALMA and/or other First Nation partners. The issue of LED classification levels and staff turnover will be discussed with regional offices as part of the reorganization activities that are occurring both in Headquarters and in Regional Operations across the country. The reorganization activities and other efforts noted above are occurring in order to develop a more coherent approach to land management as a response to the Federal Framework on Aboriginal Economic Development. | DG, Lands and Environment | ATR Manual set for delivery to First Nations fall/winter 2010/11 NALMA Training under review, due January 2011. |

| 4) a) Encourage joint/multiple collaboration between First Nations with limited capacity including continued support to Aboriginal organizations (e.g. NALMA and Tribal Councils) that support and enable capacity-building among First Nations. |

a) The initiatives highlighted in numbers 1, 2 and 3 above are based on collaboration with First Nations and will provide benefits to a full range of First Nations including those with limited land management capacity. These efforts will continue as will the pursuit of additional opportunities to work collaboratively with AFN, NALMA and other First Nations organizations. | DG, Lands and Environment | On-going |

| b) Promote greater coordination and integration between economic development and land management functions and other INAC programs such as Capital Infrastructure. | b) An independent study has provided evidence that the First Nations Land Management regime enables economic development on reserve. Using the current land management programs' strength, INAC is providing the opportunity to First Nations with land management experience to transition to sectoral self-governance. The Department encourages and provides incentives to communities using a Land Use Plan. In addition, the Department will be exploring the feasibility of incorporating economic development plans within a Land Use Plan. In addition, LED is working collaboratively with the department's capital infrastructure in Regional Operations and Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector, having established a working committee at the Director General level. | DG, Lands and Environment | On-going |

| 5) Improve financial data and monitor the implementation of the ATR and RLEMP performance measurement strategies. | 5) The Department develops the Performance Measurement Framework based on the Report on Plans and Priorities and the approved Performance Measurement Strategies. The financial component of the programs and the implementation of Performance Measurement Strategies will be monitored with quarterly reports and adjustments made as appropriate. | DG, Lands and Environment DG, Community Opportunities |

On-going |

The Management Response and Action Plan for the Impact Evaluation of Contributions to Indian Bands for Land Management on Reserve were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on September 24, 2010

1. Introduction

On September 24, 2009, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) approved Terms of Reference for an evaluation assessing the impact of INAC's land management programs.Footnote 6 The New Economy Development Group (NEDG), a consulting firm based in Ottawa with offices in the Atlantic and British Columbia regions, was contracted to perform the research. The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of INAC performed analysis and prepared the report. NEDG began work on the evaluation in December 2009 following an internal evaluation scoping exercise and initial methodology development.

The evaluation examines certain activities under the Treasury Board authority Contributions to Indian Bands for Land and Estates Management for the period covering 2005/2006 to 2009/2010.Footnote 7 The key objective of this transfer payment authority is to increase First Nations control over their land and resources pursuant to the Indian Act under land management capacity-building programs. Key activities supporting this objective include providing Indian Act "First Nations with the ability to make plans, set land use standards, determine appropriate sustainable development policies and practices, make land management by-laws, and legally control/record land transactions [in the Indian Lands Registry System]."Footnote 8 Further, the authority seeks to increase the capacity of First Nations to approve agreements, develop and operate land management systems and administer reserve and surrendered land transactions. Greater First Nation control over land management, in turn, enables economic development.

Land management capacity building and devolution programs, namely the Reserve Land and Environment Program (RLEMP) have drawn the greatest amount of funding from the Contribution Authority. The evaluation examines other programs that have drawn smaller amounts of funding from the authority, such as the Additions to Reserve (ATR) program and activities that support land management, including land surveys and the creation of legal interests.

Total expenditures under the Contribution Authority for the activities being evaluated were $46.3 million for the five-year period from 2005/2006 to 2009/2010.Footnote 9 The scope of the evaluation includes an additional estimated $76 million in direct program spending associated with supporting First Nation land managers and INAC land management on behalf of First Nations not involved in the capacity-building and devolution programsFootnote 10 This renders an evaluation scope covering a total of $122.4 million in program spending.

1.1 Outline of the Report

This report is organized as follows: Section One, the Introduction, identifies the evaluation requirement and program profile. The methodological approach and the methods used to collect and analyze the data are described in Section Two. Section Three provides the cultural, historical and legal context within which the programs operate. Section Four and Five discuss evaluation findings organized by issues of relevance, design and delivery and performance. Section Six draws conclusions against the evaluation issues. Section Seven proposes recommendations.

1.2 Evaluation Requirement

The evaluation is in response to the requirement under the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation to provide complete evaluation coverage of all grant and contribution spending. The Terms and Conditions for Contributions to Indian Bands for Lands and Estates Management were due to expire on March 31, 2010. Treasury Board has extended these Terms and Conditions for one year until March 31, 2011, to provide the necessary time to complete the evaluation.

1.3 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation covers the period from 2005/2006 to 2009/2010. The goal of this evaluation is to study the performance of the land management system as a whole, including the impact of individual program components on each other and the long-term objective of the Contribution Authority. Two central program areas are included in this evaluation: Additions to Reserve and Indian Act Land Management Programs: RLEMP, Regional Land Administration Program (RLAP) and 53/60 Delegated Authority Program. As discussed below, analysis focuses on RLEMP to best inform future programming.

The evaluation also considers a number of cross-cutting activities, including land surveys, the Indian Land Registry System (ILRS), creation of legal interests and other related activities that are important to supporting ATRs and land management. Environmental issues are considered as part of the RLEMP, namely as they apply to First Nation funding for land use planning and environment management.

In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the services delivered through the Lands Branch, the scope of the evaluation also includes operational (A-base) funding related to INAC land administration on behalf of First Nations and to support RLEMP First Nations. Given the evaluation's focus on Contributions to Indian Bands for Lands Management, the impacts of A-based funding was considered less as a main feature of the evaluation than as a point of comparison for the devolution model.

Several programs that received small amounts of funding from Contributions to Indian Bands for Lands and Estates Management were excluded from the scope of the evaluation because they have been covered in other recent INAC evaluations. These include evaluations of the First Nations Oil and Gas Moneys Management Act Implementation, Strategic Investments in Northern Economic Development, Climate Change Adaptation and First Nations Land Management Initiative. The Estates Program, which is situated under Managing Individual Affairs in the Department's Program Activity Architecture, is scheduled for evaluation in 2012-13. It was excluded from the present evaluation because it was believed that it would be better evaluated alongside individual moneys management. In addition, the training component of RLEMP was excluded to avoid duplication with another recent INAC evaluation and a recent Auditor General of Canada Audit.Footnote 11Nevertheless, design and delivery of the RLEMP is considered in relation to the achievement of outcomes.

Treaty Land Entitlement (TLE) ATRs, which make up the vast majority of ATRs, were partially included in the scope. The policy and process of ATRs in general, including success towards increasing the reserve base (namely through TLEs) were included. The claims process, which draws funding from another Contribution Authority, was excluded. An INAC evaluation of specific claims is currently underway.

Finally, it is important to note that two recent Auditor General of Canada reports were completed in 2009, which together examine TLEs and land and environment management on reserve.Footnote 12 Every effort was taken to avoid duplication of these reports, while at the same time considering important findings within the context of the present evaluation.

1.4 Program Profiles

1.4.1 Background and Description

a) Additions to Reserve

Additions to Reserve involve the transfer of either provincial Crown land or privately-held lands to the federal Crown. Through the ATR program, reserve status is granted to land that a First Nation has acquired or is entitled to receive through one of three policy categories:Footnote 13

- Legal Obligations. Legal obligations, the category under which most land was added to reserve over the evaluation period, include land obligations related to specific claim settlement agreements, court orders and legal reversions of former reserve land.

- Community Additions. The community additions category provides for the addition to an existing reserve to meet land base needs related to the normal growth of a community. It provides the means to enhance the physical integrity of a reserve most commonly road right-of-way corrections. This category also provides for the return of unsold, unsurrendered land to reserve. In order for proposals to be accepted as a community addition, the ATR must not present incremental costs to INAC regions.

- New Reserves / Other Policy. The final category encompasses a number of additional reasons for adding land to reserve, including providing land for a landless band, the establishment of reserves for social or commercial purposes, creating a reserve from provincial land offerings and, in the case of claims settlements, to provide land beyond the commitment of the agreement.

If an ATR proposal is accepted under one of the three policy categories, the selected land is subject to a 12-step review/approval process designed to ensure the selection meets basic legal and environmental requirements. An acceptable legal condition has several components. The underlying title to the land must be authoritatively established. The land must be free of other legal interests, unless arrangements acceptable to Canada and the First Nation can be made to regularize those following transfer to reserve status. Legal, service and tax-related issues with the province or, in the case of urban reserves, adjacent municipalities, must be agreed upon in advance, especially where access to utilities or local infrastructure or services is required. In some cases, for instance, when there is a need to comply with treaty provisions, the land must include sub-surface rights that are capable of being separately held, or, where sub-surface rights are not part of the reserve, satisfactory arrangements must be made for surface access to those rights for mineral development. Notes en bas de page 14 In addition, the land's boundaries must be legally determined and surveyed. The land's environmental condition must also be satisfactory.

b) Land Management/Administration under the Indian Act

There have been several developments in programming targeted at devolution of land administration duties from INAC to First Nations, specifically RLAP, 53/60 and most recently, RLEMP. While each of these programs drew some amount of funding from the Contribution Authority within the past five fiscal years, the central focus of the evaluation is on the RLEMP program, which drew the majority. It is believed that this approach will be most useful to inform future programming, particularly as RLEMP is the key INAC program for building First Nation capacity to manage land under the Indian Act, now that RLAP and 53/60 are sunsetting.Footnote 15

Regional Lands Administration Program

RLAP has been in existence since funding for land administration activities began in the 1980s. The program is based on a co-management model of land administration where First Nations partner with INAC regional land managers in implementing land administration activities required under the Indian Act. Together, the participating First Nation and INAC follow departmental policies, systems and operating guidelines.

53/60 Delegated Authority Program

The 53/60 Delegated Authority Program was introduced alongside RLAP. Under 53/60, First Nations assume land administration authority under sections 53 and 60 of the Indian Act, giving them greater autonomy to implement INAC's land administration policies and procedures.

Reserve Land and Environment Management Program

RLEMP began as a pilot in June 2005 with 15 First Nations invited from the RLAP and the 53/60 programs. Delivered to First Nation land managers, the RLEMP is intended to build new competencies and to strengthen knowledge and skills of land and environment management under the Indian Act, specifically in the areas of community land use planning, management of reserve land and natural resources, environmental management and compliance with policy and legislative frameworks.Footnote 16 In support of this objective, RLEMP provides tools, systems, procedures, templates and advice related to land and environment management and administration. A central purpose of the RLEMP is to devolve Indian Act land and environment management responsibilities from INAC to participating First Nations.Footnote 17

First Nation land managers generally enter RLEMP at the Training and Development level. Two organizations – the National Aboriginal Land Managers Association (NALMA) and the University of Saskatchewan – deliver the two-year professional training and development curriculum consisting of general land and environment management training and technical instruction in land administration under the Indian Act. After successful completion of the Professional Land Management Certification Program and approval by the regional INAC lands office, land managers progress to the operational level where they begin to provide land administration services. The final stage – Delegated Status – occurs when the First Nation receives funding, on a transactional basis, for assuming land administration responsibilities under the Indian Act. INAC continues to play an advisory and monitoring role.

INAC Land Management

In total, approximately 68 percent of First Nations in Canada operate outside of any formal INAC land management/administration program. Under the Indian Act, Canada has a statutory obligation to provide some land administration services to these First Nations and they receive support for various land administration needs, on an ad hoc basis, through regions' A-base funding. Common activities include reviewing and approving land transactions among band members; approving the allotment of individual land holdings; preparing, executing and monitoring leases, licences and permits; and coordinating reserve surrenders, designations and expropriations. It is important to note up front in this report that INAC does not manage reserve land; it administers the Indian Act as it applies to these activities.

c) Other Land Administration Activities

An initial assessment of the scope of the evaluation revealed that it would be essential to consider not only INAC's ATR and RLEMP programs but the fundamental role that various other land management activities play in supporting the land and resource management system as a whole (including resulting economic development). These activities either relate to one or both of the two key programs under evaluation or to INAC's land administration duties on behalf of First Nations:

Land surveys.

Surveys are conducted to define allotments to individual band members, leases, permits and other limited interests, a parcel of land for alienation, or to re-establish or restore boundaries.Footnote 18 Surveys are required during the ATR process to determine the boundaries of the prospective reserve land. Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is an important partner in the delivery of the survey program. NRCan's role historically has been as corporate surveyor for Canada. The Department fulfils a steward role by providing specifications for survey work, managing surveys and boundary work, ensuring standards are met and maintaining official records. And, it fulfils a facilitation role through its administration of various programs.

Creation of legal interests / Registration of legal interests under the Indian Act support economic development initiatives by allowing access to reserve lands and resources through various tenure instruments and agreements, including leases, permits, easements, designations and surrenders. Legal interests can be created both for First Nation and non-First Nation entities. Examples range from mining and timber permits to commercial leasing to arrangement with band-owned corporations. Of all of these interests, only funding used for commercial leasing was drawn from the Contribution Authority under analysis. However, the evaluation discusses to some extent, negotiation and transfer of legal interests related to fulfilling Crown obligations for the transfer of title under the ATR process.Footnote 19 Creation of legal interests is performed with support from the Department of Justice (DoJ). ILRS is a database containing instruments relating to transactions on reserve lands. The system permits the generation of inquiries and reports by First Nation reserve.

1.4.2 Program Objectives

a) Additions to Reserve

The objectives of the ATR program are to:

- Ensure that all steps necessary for effective transfer of land are completed and all third-party interests are properly recorded and addressed;

- Ensure that all environmental concerns are identified and addressed;

- Promote good ongoing relationships with neighbours, third parties, municipalities, and provincial governments; and

- Balance the interests of First Nations, government, third parties, and the public.

b) Land Management: Reserve Land and Environment Management Program

According to the RLEMP Program Manual, the program objectives are to:Footnote 20

- Strengthen First Nation governance and improve accountability;

- Deliver an integrated training approach with skill development and institutional support;

- Increase involvement of First Nations in the full scope of land management and environmental activities on reserve;

- Provide opportunities for alignment with the First Nations Land Management (FNLM) Regime, treaty processes and self-government;

- Establish linkages between funding, scope of activities and results, as well as financial sustainability; and

- Increase First Nations' involvement in the core functions of community land use planning and environmental compliance.

c) Other Land Management Activities

Land surveys. Objectives and expected outcomes of the Land Survey Program are to ensure that the statutory duties of interests in Indian lands are carried out in accordance with the Indian Act and Canada Land Surveys Act. Beyond these obligations, the program engages in a number of activities, including providing advisory services; setting guidelines for survey work; disseminating land survey, mapping, imagery and land registry information; and working to ensure that external reserve boundaries and internal allotments are clear, unambiguously described and registered in ILRS.Footnote 21

Creation of Legal Interests / Registration of Legal Interests in Reserve Land According to representatives from the Lands Branch, a key expected result of this activity is to support First Nation goals for economic development, specifically, through the activation of their land base to generate income either directly through rent or indirectly by attracting business on reserve. Registration of legal interests contributes to certainty of possession.

1.4.3 Program ResourcesFootnote 22

Table 1 below shows the total amount of contribution funding allocated to each program or activity under analysis. Of the total amount of funding allocated to land management/administration and ATR activities (calculated as the A-base funding and contribution amounts combined), contribution funding comprised 38 percent, while A-base funding (salary and operation and maintenance) represented 62 percent. Later in the report, findings will highlight that INAC continues to play a significant role in land administration as the Department builds capacity among First Nations and works towards devolution of its Indian Act duties.

| Activity | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | Total By Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Addition to Reserves |

$434,145 (4% of annual total) |

$758,692 (7%) |

$1,022,461 (11%) |

$118,900 (1%) |

$364,840 (14%) |

$2,699,038 (6% of G&C Total) |

| 2. RLEMP, RLAP, 53/60 | $9,725,360 (89%) |

$9,079,155 (83%) |

$7,876,230 (84%) |

$10,588,481 (86%) |

$1,985,870 (74%) |

$39,255,096 (85%) |

| 3. Other Activities | ||||||

| Surveys | $608,929 (6%) |

$766,531 (7%) |

$0 (0%) |

$615,430 (5%) |

$0 (0%) |

$1,990,890 (4%) |

| Commercial Leasing |

$204,712 (2%) |

$319,300 (3%) |

$500,470 (5%) |

$991,481 (8%) |

351,128 (13%) |

$2,367,091 (5%) |

| Total Contribution | $10,973,146 (49% of annual G&C + O&M) |

$10,923,678 (44%) |

$9,399,161 (36%) |

$12,314,292 (42%) |

$2,701,838 (13%) |

$46,312,115 (38% of annual G&C + O&M) |

| O&M + Regional Salary Dollars | $11,404,920 (100%) |

$11,754,295 (86%) |

$11,879,624 (72%) |

$12,739,287 (76%) |

$13,443,163 (77%) |

$61,221,289 (81%) |

| O&M + HQ Salary Dollars | N/A | $1,929,917 (14%) |

$4,732,706 (29%) |

$4,144,573 (24%) |

$4,058,320 (23%) |

$14,865,516 (20%) |

| O&M + Salary - Grand Total | $11,404,920 (51%) |

$13,684,212 (56%) |

$16,612,330 (64%) |

$16,883,860 (58%) |

$17,501,483 (87%) |

$76,086,805 (62%) |

| Grand Total: Contribution + O&M | $22,378,066 | $24,607,890 | $26,011,491 | $29,198,152 | $20,203,321 | $122,398,920 |

a) Additions to Reserve

Between 2005/2006 and 2009/2010, the ATR Program drew $2.7 million from the Contribution Authority for non-TLE activities. Most of this funding was allocated to activities in British Columbia ($820K), Alberta ($220K), Ontario ($720K), Quebec ($110K), Saskatchewan ($330K), and Manitoba ($280K). The remaining funds were allocated to 17 projects in the Atlantic region ($10K) and one project in the Northwest Territories ($200K). ATR funding was provided to First Nations, which have an ATR proposal accepted under the "Community Additions" category. This funding provided support to First Nations for the selection of the new land and, land surveys and in negotiations related to third party interests who have an interest in the new reserve land.

b) Land Management: RLEMP, RLAP & 53/60

Between 2005/2006 and 2009/2010, RLEMP, RLAP and 53/60 drew some $39.3 million from the authority. Regions receiving the highest proportion of funding were Saskatchewan (33 percent), Ontario (23 percent), and British Columbia (18 percent).Footnote 23

c) Other Land Management Activities

A relatively small amount of funding was spent through the Contribution Authority on surveys ($1.9 million) and commercial leasing ($2.4 million) between 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 to support the ATR program and economic development on reserve. However, these activities are mostly supported through NRCan and DoJ A-base funding (these figures were not available). As will be discussed in greater detail below, INAC also transferred a total of $4.9 million to NRCan in surplus departmental operational funding late in each fiscal year for surveys to NRCan over the evaluation period.Footnote 24 Additional funding for supporting activities for ATR and RLEMP programs arrives at the regional level through the INAC's Environment Program.Footnote 25

1.4.4 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

a) Additions to Reserve

Most of the ATR steps are carried out at the regional level working with First Nations. The Director General of Lands Branch, Lands and Economic Development (LED) Sector at Headquarters (HQ) is responsible for providing national coordination of the program, including the approval of ATR either through the Minister, in accordance with either of the two existing Claims Implementation Acts, or the Governor General in Council if the reserve is being created through Royal Prerogative.

Key stakeholders include NRCan and Environment Canada, (NALMA), provincial governments, municipal governments, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and third parties with legal interests in the land. ATRs may also present cost implications to other departments, such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Health Canada through increased service requirements. In some ATRs, Justice Canada plays a facilitative role in providing legal support and negotiation advice and aids in moving legal instruments and documents associated with legal interests and easements to closure. Indian Oil and Gas Canada assists with creating leases in ATRs involving resource development and plays an educational role both with First Nations and resource companies. Key beneficiaries are the First Nations receiving additional reserve land through the ATR process.

b) Land Management: Reserve Land and Environment Management Program

Responsibility for monitoring and assessment at the program-level rests with the regional directors general and at HQ with the Director General of the Lands Branch. Two to three workshops with the Professional Land Management Certification Program Steering Committee (i.e., INAC, NALMA and the University of Saskatchewan) are held annually to discuss status and performance, region-specific issues/concerns and emerging issues in land, resource and environment management. At the agreement-level, responsibility for monitoring the finances and program progress rests with the regions. Regional land offices provide advisory and technical support to First Nations land managers.

Key stakeholders include NALMA, the University of Saskatchewan and other First Nation and non-First Nation associations that focus on land, resources and environmental management issues. Key beneficiaries are the First Nations participating in the RLEMP.

c) Other Land Management Activities

Surveys. Regional offices perform most activities related to land surveying, including identifying survey requirements, processing survey proposals and approving survey plans. INACHQ provides advisory services, performs a quality assurance role, and provides ministerial approval of survey plans. The key partner in the delivery of the surveys program is NRCan, specifically the Earth Sciences Sector of the Department, which provides technical support. Key beneficiaries of this function are First Nations and others with legal interests in reserve land who are afforded greater certainty of possession.

Creation of Legal Interests / Registration of Legal Interests in Reserve Land. INAC HQ sets the policy, based on legal requirements, for drafting, issuing, cancelling and registering legalinterests as well as administering leases and permits. INAC regions and DoJ work with First Nations to administer transactions. INAC regional lands officers are responsible for ensuring that the Department's policy requirements are met for preparing, executing and registering leases and are also available to provide support during negotiations.Footnote 26 DoJ Counsel provides legal advice and support. Operational RLEMP First Nations are responsible for registering transactions. The beneficiaries of this activity are First Nations who benefit through the activation of the economic development potential of their land and other stakeholders (i.e. leasees) afforded the opportunity to use reserve land.

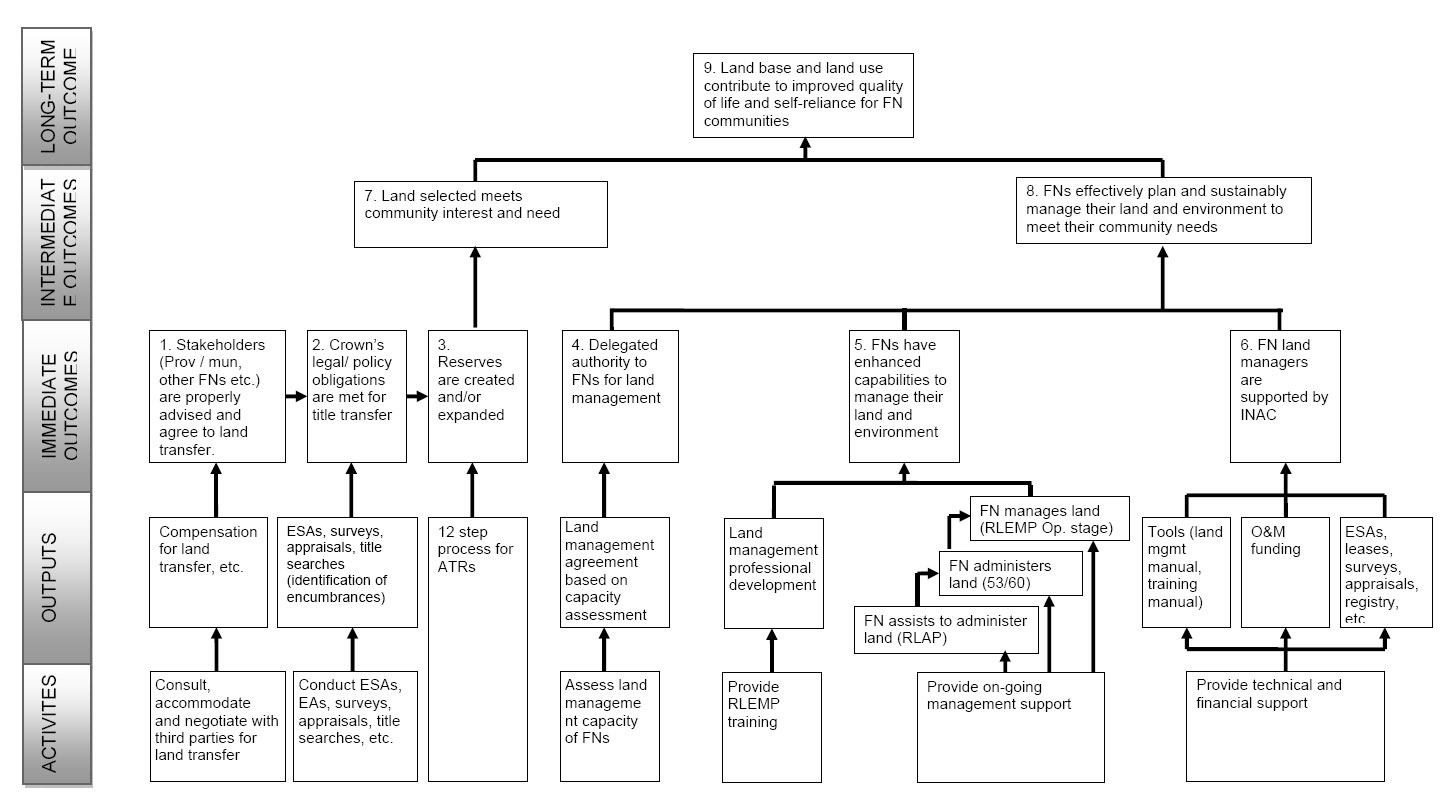

1.5 Logic Model

Logic models are used to demonstrate linkages between program activities, outputs and intended outcomes. They provide a conceptual foundation upon which performance indicators can be built. In the absence of a logic model that incorporated all activities considered in this evaluation, EPMRB developed the model on the following page and received verification from program managers. It is primarily divided along the lines of the two central programs under evaluation.

Activities and outputs show the efforts and tangible products that result in outcomes. Immediate outcomes are those over which the Department has considerable influence and that occur in a short period of time. One example in relation to RLEMP is the enhanced capability of First Nation land managers to manage land. One or more immediate outcomes contribute to intermediate outcomes. Following the same example, over time, given adequate and ongoing support from INAC and considering external influences, enhanced capabilities should result in First Nations effectively planning and sustainably managing their land and environment to meet their community needs. The long-term outcome speaks to a change in the state of being of Aboriginal communities that may occur as a result of these programs and others. Findings in Sections 4 and 5 below are organized around the outcomes identified in the logic model.

Figure 1: Logic Model for the Impact Evaluation of Contributions to Indian Bands for Lands Management*

Description of Figure 1

Figure 1 illustrates the logic model for the Impact Evaluation of Contributions to Indian Bands for Land Management on Reserve. The model shows the links between activities; outputs; and immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes. The purpose of the model is to demonstrate how impacts are expected to result from the program's activities and outputs. The model is generally organized around two main program areas: 1) the Additions to Reserve program (ATR) and 2) Reserve Land and Environment Management Program (RLEMP) and Indian and Northern Affairs (INAC) land management services.

ATR activities, outputs and outcomes

The left half of the model describes the ATR program. The first activity shown is to consult, accommodate and negotiate with third parties for land transfer. This leads to the output of compensation for land transfer, etc. and, in turn to the immediate outcome of stakeholders of the program being properly advised and agreeing to land transfer.

The second activity and set of outputs related to the ATR program is to conduct environmental site assessments, ESAs, surveys, appraisals, title searches. These and other activities contribute to the immediate outcome of meeting the Crown's legal/ policy obligations title transfer.

The third and final set of activities and outputs of the ATR program is the 12-step process for ATRs, which outline the complete set of activities involved in the transfer of land. It is expected that these activities and outputs will lead to the creation and/or expansion of Indian reserve land.

The achievement of these lower-level activities, outputs and outcomes in theory, will lead to the intermediate outcome of land selections that meet the interest and need of First Nations communities.

RLEMP & INAC Land Administration Services activities, outputs and outcomes

The first activity shown in the model related to the RLEMP program is to assess the land management capacity of First Nations. This activity leads to the output of land management agreements between INAC and First Nation land managers, which directly leads to the immediate outcome of delegated authority to FNs for land management.

The next two activities – providing training and on-going management support – lead to outputs associated with delivering the land management capacity-building programs to First Nations and providing land management professional development. It is expected that these efforts will enhance First Nations' capabilities to manage their land and environment, which is identified as an immediate outcome in the logic model.

The final activity conducted as part of INAC's land administration services is to provide technical and financial support. Several examples of outcomes related to this activity include: tools such as the land management manual; program funding; and land administration activities such as environmental site assessments, leases, surveys, appraisals, land registry, etc. Together, these activities and outputs if delivered properly should result in the immediate outcome of First Nation land managers being supported by INAC.

The three immediate outcomes listed above lead to the intermediate outcome of First Nations effectively planning and sustainably managing their land and environment to meet their community needs.

Long term outcome

The ultimate outcome included in the logic model is expected to be realized over time and with the achievement of intermediate outcomes from the ATR and RLEMP / INAC land administration services programs. This outcome is: Land base and land use contribute to improved quality of life and self-reliance for FN communities.

*Note graphics are included in this document for reference only

2. Methodology

2.1 Overview

Phase 1: Establishment of the Evaluation Working Group and Advisory Committee. An Evaluation Working Group consisting of six representatives from each directorate associated with the evaluation and, including regional representation was assembled early on to act in an advisory role.Footnote 27 The committee provided invaluable support throughout the evaluation, both clarifying complex program specific issues and assisting in the development of the scope and methodology of the evaluation.

In addition to the Working Group, EPMRB established a five-member Advisory Committee comprised entirely of Aboriginal people. Members included Aboriginal land managers, academics, Elders and others with knowledge of land management on reserve. The committee was instrumental in drawing connections between Aboriginal people and the land and providing insights into Aboriginal interests in land management.

Phase 2: Evaluation Assessment and Methodology Development. Early in the evaluation, EPMRB reviewed all available program documentation and developed a logic model and evaluation matrix that identified evaluation questions and related performance indicators. Following this initial scoping and methodology development, the Evaluation Team conducted a detailed evaluation assessment, involving consultations with INAC officials at HQ and across all regions and further engagement of the Working Group. The evaluation assessment was essential to operationalizing the approach to the evaluation, for instance through the development of meaningful key informant interview questions.

Phase 3: Data Collection. Discussed in detail below, a number of methodologies were developed in order to fully understand the range of programs and activities under evaluation.

Phase 4: Reporting. Following data collection, performed by NEDG, EPMRB and NEDG prepared technical reports with detailed analysis for each line of evidence. EPMRB fed information from these reports into a draft report underwent review by the Working Group members before being tabled at INAC's EPMRC meeting on September 24, 2010.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The organizational structure of the evaluation focuses on relevance and performance, and follows the five core evaluation issues as outlined in the 2009 Treasury Board Secretariat Evaluation Policy and Directive: Relevance: continued need for program; alignment with government priorities; alignment with federal roles and responsibilities; and Performance: achievement of expected outcomes and demonstration of efficiency and economy

Ten key evaluation questions were developed in an Evaluation Matrix to address the core issues. The matrix includes a set of performance indicators upon which the evaluation report's findings, conclusions and recommendations are based and identifies the various data collection methods used for the evaluation questions and , as well as sources of data.

2.3 Evaluation Methods

The evaluation has drawn upon multiple lines of evidence to fully address the core evaluation issues and questions. These include a document and literature review, a financial and performance data review, an historical and legal review, key informant interviews, case studies and an Elders roundtable discussion. Refer to the Evaluation Matrix in Annex B for more information.

2.3.1 Data Sources

Document and Literature Review. A document review was undertaken to collect and review documents that address the evaluation questions. It provided evidence for the rationale of the programs, their alignment with government priorities and relevant roles and responsibilities of INAC. Documents also contribute to an understanding of the historical and legal context of land management and support case studies.

In total, over 300 documents were identified for use in this evaluation. These included: INAC reports (HQ and regions); reports from other federal departments (i.e., NRCan and DoJ); audits, evaluations and management reviews; academic articles; and reports from First Nations and First Nation organizations. Documents were gathered through program managers and an extensive internet scan.

Financial and Performance Data Review. The evaluation undertook a review of the financial contributions provided to First Nations under the Contributions to Indian Bands for Lands and Estates Management authority and a review of the salary allocations provided to the Land Branch (HQ and regions) from the Department's A-base budget. A review of the available performance data related to ATR and RLEMP activities was undertaken.

Historical-Legal Review. Early in the development of the methodology, the Evaluation Team determined that it was essential to provide appropriate legal and historical context to understand and appreciate the intricacies, limitations and opportunities of land management under the Indian Act. The Historical-Legal Review focuses on issues identified in commentaries on Indian reserve land management and discusses applicable statutes, regulations and decisions of the courts. Information from ten interviews with DoJ officials from across the country supports this analysis and provides perspectives on INAC's fiduciary obligation to First Nations in an increasingly complex environment.

Key Informant Interviews. Following the scoping exercise, eight key stakeholder groups were identified with the following responses from each: INAC Senior Officials (HQ and regions) (N=5); INACHQ Land Managers (N=13); INAC Regional Land Managers (N=23); FN Land Managers (N=16); Aboriginal Organizations (N=6); NRCan (land surveys) (N=5); DoJ (N=10); and Other Government (namely provinces and municipalities) (N=13). In total, 128 interviews were conducted. The researchers conducted 91 key informant interviews. An additional 37 stakeholders were interviewed to collect data as part of the Case Study research. Refer to Annex A for more detailed information on the interview groups.

Elders Roundtable. In response to the Advisory Committee's recommendation to speak to Elders about Aboriginal peoples' relationship with the land, the Evaluation Team was invited to participate in a roundtable discussion with six Elders representing First Nations from across Canada. This meeting was held over a two-day period in a traditional manner and was co-facilitated by the Elder who hosted the meeting. The results of this discussion form the foundation of this evaluation report by clearly establishing the significance of land to Aboriginal people, their culture, economies and overall quality of life.

Case Studies. Five case studies were examined as part of the evaluation. The case studies were selected with input and guidance from both the Advisory Committee and Working Group. Several criteria were employed during the selection process: the studies had to investigate key issues in each of the areas of inquiry and, have broad implications and, to the greatest extent possible, provide even coverage of the regions south of 600. The case studies brought together several methodologies, including a review of documents (drawn from both First Nation communities and INAC); focus groups and key informant interviews with INAC officials, First Nations and other stakeholders.

- Expediting ATRs through stakeholder cooperation: an assessment of how one First Nation, INAC, the province, rural municipality and other stakeholders worked co-operatively to allow the First Nation to take advantage of economic opportunity.

- Impacts and benefits of a strong survey fabric on land use planning and economic development: how one First Nation is employing the tools of modern land management.

- Impacts and benefits of RLEMP on environmental and integrated land use planning: how two First Nations environmental and land use planning issues.

- A model in providing land management services to First Nations that lack capacity: how one tribal council works with six small First Nations to meet their land management responsibilities and plan for the future.

- On the way to self-government: how one First Nation enters into land transactions outside of the Indian Act in order to expedite economic development and increase self-reliance.

2.3.2 Presentation of findings

The following terms are used throughout the report to refer either to the proportion of key informants in agreement or the frequency with which an opinion was expressed:Footnote 28

| Proportional Term | Frequency Term | Percentage Range |

|---|---|---|

| All | Always | 100% |

| Almost all | Almost always | 80-99% |

| Many | Often, usually | 50-79% |

| Some | Sometimes | 20-49% |

| Few | Seldom | 10-19% |

| Almost none | Almost never | 1-9% |

| None | Never | 0% |

2.3.3 Limitations and Mitigating Strategies

It is important to note that a number of limitations – both in methodology and analysis – constrained the ability of the evaluation to report on some findings.

Performance measurement information. Inadequate performance measurement information and difficulties with performance measurement systems limited analysis in some areas.Footnote 29

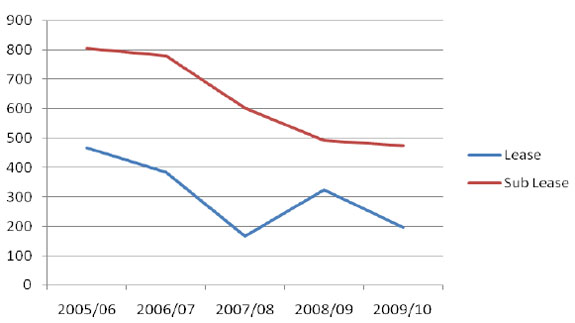

- Indian Lands Registry System. It was difficult to extract meaningful data from the ILRS system because the system collects information by reserve and not by band. The Evaluation Team was unable to conduct a comparison of transactions registered by RLEMP First Nations and INAC, which would have been a useful indication of the success of the program. Analysis relies instead on national totals.

- Additions to Reserve. The ATR tracking system had significant reliability problems until about three years ago and the new National ATR Tracking System (NATS) has only been fully operational in the last few months. A useful indicator of the extent to which the ATR program is meeting First Nations needs, for which data was unavailable, is the number of ATR proposals that are not accepted including rationale for rejection. Most data on processing times, a key indicator of efficiency in ATR delivery was not available at the time of the evaluation. These data are now being collected through NATS . The ATR program recently completed a performance measurement strategy.

- RLEMP and INAC Land Administration. The RLEMP tracking system is limited to collecting data on numbers of land managers involved in each of the programs, RLAP, 53/60 and RLEMP. It does not collect data related to land management activities, such as number and type of land transactions. One useful indicator of the effectiveness of INAC's land management support that is currently not being collected is the length of time it takes to execute a lease. RLEMP has completed a performance measurement strategy as part of the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development.

This limitation meant that performance information had limited application in analysis and was used generally as a descriptive tool. Another impact on the evaluation was the difficulty in trend analysis over time. To mitigate these shortcomings, analysis made use of as much relevant performance information as possible, supplementing gaps with other methodologies.

Financial data. The Evaluation Team encountered several instances where financial information from INAC and other government departments either was unavailable or imprecise. Since salary amounts are not allocated on a program basis and the organizational structure of each region differs, it was difficult to gather consistent salary information from the regions. As well, financial data on HQ salary allocations, while available for 2006-07 to 2009-10, were not available for 2005-06 because there was a change in financial systems at that time. A-base financial information from NRCan and DoJ related to surveys and creation of legal interests was not available.

These shortcomings limited the extent to which financial data used in the evaluation is comparable and reliable across regions and over fiscal years. It also made it difficult to understand the full cost of activities related to land management. For instance, without access to operational financial information from NRCan and DoJ, the evaluation could not determine the true cost of surveys and creation of legal interests to the Government of Canada. Financial limitations were mitigated by ensuring full collection and analysis of all available financial data, including INAC contribution and operational funding. These data, though imprecise at times, allow for some trends to be determined over time and by activity.

Expected outcomes. Few expected outcomes were available at the time of evaluation design, making it difficult to measure whether progress had been made over time. This limitation made it difficult to evaluate the programs and activities against agreed upon outcomes that they had been working towards over the past five years. To mitigate this issue, the Evaluation Team developed a full logic model and evaluation matrix, complete with outcomes and performance measures based on an understanding of the purpose and objectives of the programs. Program managers provided input and validated the model before the evaluation began. This exercise helped inform the concurrent development of performance measurement strategies for the ATR and RLEMP programs with the goal of establishing a baseline understanding of performance in the present evaluation and tracking this over time.

Data collection and triangulation of evidence. Although every effort was made to gather balanced evidence for each of the evaluation questions, in a few cases, the Evaluation Team had to rely on few lines of inquiry or limited variation of sources within one line of inquiry to address evaluation questions. The best example of this is can be found in analysis related to the extent to which stakeholders, including provincial and municipal governments, other First Nations with overlapping claims and other stakeholders have been engaged and accommodated in the ATR process. Unable to make contact with representatives from these stakeholder groups with the exception of several interviews conducted during a case study, analysis relies heavily on key informant information from INAC officials and First Nation land managers.

This limitation presents the potential for bias as the views from only several groups are relied on in some cases. This was mitigated through a thorough review of documents and literature related to municipal government involvement in ATRs. A case study on TLEs in Saskatchewan targeted provincial, municipal and third party players to better understand the web of relationships that makes adding land to reserve possible.

Gender-based analysis. The evaluation was unable to conduct gender-based analysis given a lack of performance information and the inherent difficulty in applying a gender-based lens to land management. The Evaluation Team considered examining matrimonial real property, but it was decided that inclusion of this issue would push the boundaries of an already ambitious scope. Gender-based analysis has been considered in both the ATR and RLEMP performance measurement strategies and recently, a study has been completed on gender-sensitive indicators for RLEMP through a partnership with INAC's Gender-based Analysis Directorate, EPMRB and the program.

Sustainable development. Discussions held with the Sustainable Development Directorate indicate that principles on sustainable development were in place and available to program managers beginning in 2007 (i.e., mid-way through the evaluation period). As a result, there is no performance data related to sustainable development and little indication that its principles were considered at the time of program design. The report includes limited discussion of sustainable development in analysis.