Archived - Impact Evaluation of the Income Assistance, National Child Benefit Reinvestment and Assisted Living Programs - Final Report

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: February 10, 2009

PDF Version (417 Kb, 76 pages)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

- 2.0 Evaluation Methodology

- 3.0 Income Assistance Program Evaluation Findings

- 4.0 NCBR Program Evaluation Findings

- 5.0 Assisted Living Program Evaluation Findings

- Action Plan

List of Acronyms

| AL | Assisted Living Program |

| AES | Audit and Evaluation Sector (of Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch) |

| AG | Auditor General of Canada |

| AHRDA | Aboriginal Human Resources Development Agreement |

| AHRDS | Aboriginal Human Resources Development Strategy |

| ASARET | Aboriginal Social Assistance Recipient Employment Training |

| CFA | Comprehensive Funding Agreement |

| CFNFA | Canada First Nations Funding Agreement |

| ECE | Early Childhood Education |

| EQAO | Education Quality and Accountability Office (Ontario) |

| FASD | Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder |

| FN | First Nation |

| FNIHCC | First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program |

| GOC | Government of Canada |

| HRSDC | Human Resources and Social Development Canada |

| IA | Income Assistance Program |

| INAC | Indian and Northern Affairs Canada |

| NCB | National Child Benefit |

| NCBR | National Child Benefit Reinvestment Program |

| NCBS | National Child Benefit Supplement |

| OCAP | Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (i.e. of First Nations Data and Information) |

| PCH | Personal Care Home |

| RBAF | Risk-Based Audit Framework |

| RMAF | Results-Based Management and Accountability Framework |

| RRG | Recipient Reporting Guide |

| SA | Shelter Allowance |

| TESI | Training Employment Support Initiative (Government of B.C.) |

| WOP | Work Opportunity Program |

Executive Summary

Introduction

The objective of this evaluation is to provide evidence to Treasury Board of the degree to which INAC's Income Assistance (IA), Assisted Living (AL), and National Child Benefit Reinvestment (NCBR) programs are achieving their intended outcomes. As evaluations of IA and NCBR had been completed as recently as last year (2007), and a thorough program review of AL was completed in the same period, this evaluation was intended to have a different focus.

As not enough information about impacts was provided in previous evaluations, the intended focus of this evaluation was to be on the impacts of these programs on First Nations communities, service providers and clients. Accordingly, a great deal of the effort put into the evaluation was directed at carrying out case studies in ten First Nation communities across the country that represent regional variations in service delivery, varying degrees of size and remoteness, and differing funding agreements guiding program and reporting requirements. Most of the case study communities delivered all three of the programs under review. Key informant interviews and literature and document reviews provided the evaluation team with the overall policy and program context in which the ten communities are operating, and in most cases, struggling to meet the often unique and challenging needs of community members.

Methodology

The evaluation developed multiple lines of evidence gathered through the following activities:

- A review of 331 Documents;

- A review of 25 Literature Sources;

- Review of 129 Administrative and Financial Data Documents;

- 17 Key Informant Interviews;

- 10 Community Case Studies, that included:

- 77 interviews with community service providers;

- 181 community surveys, principally with IA recipients;

- 8 focus groups involving 78 IA/NCBR end-users;

- 32 surveys of AL end-users;

- Review of community documents/data sources.

- An Expert Panel on Assisted Living (5 participants);

- An Expert Panel on Income Assistance/NCBR (5 participants).

Overall Evaluation Findings

Overall, but to varying degrees, the three programs continue to meet vital socioeconomic and health needs in First Nations. One of the principal observations the evaluation would like to convey is the complexity of the issues under review, and that the deep and complex situation of on-reserve social needs and the programs designed to meet those needs, requires complex and long-term solutions. Adding to the complexity of the situation is INAC's policy of matching provincial programs; this results in significant variability in Income Assistance rates and measures across the country, and in Assisted Living program policy and delivery. Consequently, although one of the evaluation recommendations is to review IA funding in order to ensure basic needs are met, there are companion recommendations for integrated and long-term solutions that address the root causes of poverty and unemployment on reserve. Long-term solutions, are, however, just that; while they are being designed and implemented, ideally as part of a national strategy, basic needs funding may need to increase in the short-term.

Before outlining specific program findings, the report begins by presenting the challenges to achieving an impact evaluation. Despite these challenges, the case study method has provided a depth of analysis that offsets many of those challenges.

There are a number of significant challenges to achieving a meaningful assessment of program impacts, some of which were outlined in the 2007 evaluations. A number of the most salient are:

- Lack of Meaningful Outcome Indicators: INAC is in a challenging position: to meet Treasury Board accountability requirements, the department is asked to provide evidence of program impacts, while historically the frameworks for such evaluation and performance measurement have not been in place. In order to have meaningful evaluation data available for a good assessment of program impacts, evaluation frameworks outlining meaningful outcome indicators are required to direct data collection. INAC, in line with the overall culture of evaluation evolving across GOC departments, has developed a draft RMAF, including a logic model, but is in the process of developing a more robust performance measurement strategy aimed at providing better evidence of program impacts, to reflect the Treasury Board policy on transfer payments. That have such indicators for future evaluations, but at present the data collected can say little about impacts on end-users, service providers and communities as a whole. As these are targets of desired social development outcomes for Aboriginal people at the horizontal GOC level, the evaluation goal needs to be the collection of outcome data that shows program impacts at all of these levels.

- Policy and Program Variability Nationally: Evaluations are challenged by the wide range of variability of the programs from one region to the next, and in the case of NCBR, from one First Nation to the next. As the driving policy principle for both IA and AL is comparability with analogous provincial programs, the result has been a diverse mix of policies and program elements all under the INAC umbrella. In some regions, INAC is principally a funder, and in others, provides service directly to clients. Painting a coherent national picture of any one of these programs is an extremely complex task.

- Consistency and comparability of data: In part as a result of the policy and program variability just discussed, and in part a result of data system inconsistencies from region to region, evaluations are challenged to obtain a consistent and comparable set of data. Data frequency and type also varies within regions, according to the reporting requirements of the funding agreements particular First Nations have with INAC.

- Capacity issues at all levels: There are staff shortages at the national, regional and community level. Existing staff at the community level need training in the purposes and methods of good data collection; but there are also capacity shortages at the regional and national levels in data management and interpretation, and in reporting back to regions and communities for purposes of outcome-based program planning.

Overall Evaluation Recommendations

Outlined below are recommendations applicable to all three programs:

- Create an Evaluation working group of INAC Audit and Evaluation Sector and Program Staff, and First Nations representatives to develop outcomes indicators for all three programs that will be meaningful and acceptable at the community level;

- Develop a standard data system and standardization of indicators for all regions to facilitate comparability;

- The Working Group Created should have a discussion of OCAP[Note 1] principles regarding program data.

Income Assistance Program Findings

The Program Continues to be Relevant: Community profiles prepared for each of the case study communities, as well as regional and national data, show that high levels of poverty, low educational attainment levels, high unemployment levels; poor housing conditions and overcrowded housing persist in First Nations communities, highlighting a continued need for income assistance until long term alternatives and solutions are found.

Basic Needs Are Reportedly Not Met: Despite the fact that almost 90% of the IA budget is directed to basic needs, there is virtually universal agreement by staff and end-users that basic needs are not being met. Explanations for this may include the following:

- INAC follows provincial rates, which are based on urban, rather than remote rural needs. Amounts payable under the income assistance program are based on the eligibility criteria and rate schedules of the reference province or territory.

- More than price differentials for goods in most cases, the costs of transportation are prohibitive for IA recipients, who reported having to pay taxi fares to nearby towns to buy clothes and/or food, in the absence of public transportation.

- A complex shelter regime means that shelter costs are not paid in all regions, with the result that many recipients are left with not enough revenue for food, clothing, transportation, and personal items after rent has been deducted from their benefits.

- Utility costs, particularly home heating, are reportedly higher in many First Nations communities than national averages. Expensive electric heat is often the only option, and housing stock in poor condition exacerbates heating costs.

- Transportation is a basic need in the communities surveyed. Lack of transportation is a barrier to meeting other basic food and supplies needs, but also to accessing employment.

Number of Single Recipients Rising: The proportion of single recipients to the entire caseload has grown over the past few years. Community perceptions reported in this evaluation are that the majority of these are youth who choose to access income assistance when they turn eighteen. The evaluation was not able to access the detailed client information that would support or negate this perception, although both community members and service providers alike made the observation. More than 50% of those who participated in the end-user survey were under the age of 35.

Supports for Effective Long term Solutions Widely Lacking: It is acknowledged that active measures and integrated approaches, including client case management; tailored approaches to employability and job readiness barriers; addressing education and training needs; and providing supports to parents such as training funds and child care, are effective at finding long-term solutions to low employment and high welfare dependency levels. While such approaches are being implemented by some provinces,, only a very small percentage (less than 2%) of INAC's IA expenditures go to supporting such measures. If the desired outcome is to alleviate hardship by supporting employable First Nations members currently on IA into long term employment, such measures will be part of an integrated and complex social development strategy by INAC. In addition to ensuring that basic needs are met in the short term, the long term solutions will require the funding and support of such measures in partnership with other relevant agencies such as HRSDC and provincial education and training bodies, as part of an integrated national strategy.

Long term Outcomes of Employment Support Measures Unknown: For the employment support measures that INAC has funded, there is insufficient evidence to be able to comment on their effectiveness. The measure currently used, "Person Months of Employment" is a rough measure, and does not provide information about the long term employment outcomes for an individual, or other critical information regarding employability and long term "alleviation of hardship." The survey of end-users in this evaluation was not able to capture this information, as those who would have successfully transitioned to work from welfare were not part of the sample.

Staff Capacity to Engage and Support Community Service Providers is low: National and Regional INAC staff capacity is not sufficient to provide the supports and engagement needed by community service providers to build their own capacity and enhance their service provision. Key informants at all levels reported this issue.

INAC's role and mandate for IA is questioned within the department: Most key informants within INAC see their role as "funder," and some question whether INAC should continue providing income assistance, or whether this is a provincial role. As one of the chief policy drivers is currently the requirement for INAC regions to match provincial rates and eligibility requirements, it is difficult for INAC to set meaningful IA policy; to do so would require collaborative discussions with the respective provincial ministries.

Income Assistance Program Recommendations

- Develop, in partnership with relevant bodies such as HRSDC, AFN, and provincial ministries, an integrated strategy to address on-reserve labour and employment needs. The strategy would recognize the complex and unique needs of the on-reserve unemployed, such as restricted access to labour markets; multiple employability barriers; transportation needs; and the need for child care and other necessary supports while in training or educational upgrading programs.

- In the near term, until a strategy to address the causes of welfare dependency is in place, and achieving the desired outcomes; and to provide better support for basic needs: review the 2% funding increase policy to assess whether it is meeting First Nations IA costs;

- In the near term, address INAC staffing shortages and training needs at the national and regional levels;

- In the near term, fund a representative sample of community needs assessments that will provide meaningful cost measures for items such as shelter, utilities and transportation;

- In the longer term, create a working group of INAC, First Nations and Provincial representatives to develop a strategy for addressing IA jurisdictional and funding issues, including a discussion of the costs of needs in rural/remote communities;

- Take the lead in initiating an integrated education and training strategy with HRSDC, Aboriginal organizations, and relevant provincial ministries, to address the education needs of First Nations youth in particular, as a way of reducing the number of youths who choose welfare over further education and/or employment;

- Strengthen links with other relevant departments such as HRSDC to enhance information sharing so that long term employment outcomes can be measured, and develop more refined outcome indicators for future evaluation activities.

National Child Benefit Reinvestment Program Findings

The Program is Relevant: Case study community profiles as well as national and regional statistics show that continuing levels of poverty, high levels of unemployment, low educational attainment levels, scarcity of jobs, and the high percentage of children in First Nations populations show a continuing need for supports to low-income parents and children.

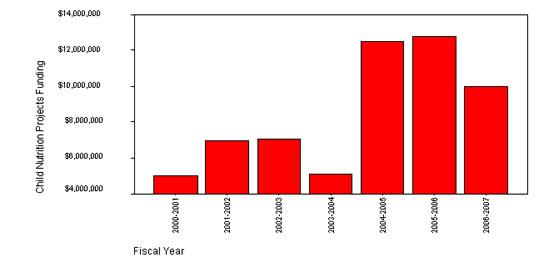

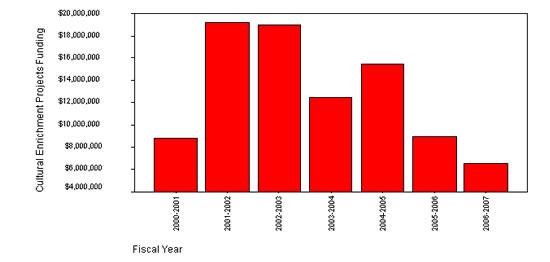

The Program is Meeting Community-Defined Needs: The evaluation found that NCBR programs are valued and responding to community-defined needs. The flexibility of the program, while posing challenges for reporting, appears to be a strength from this perspective. In particular, programs that provide hot breakfasts and/or lunches to children are highly valued by parents and educators, as are cultural teaching programs.

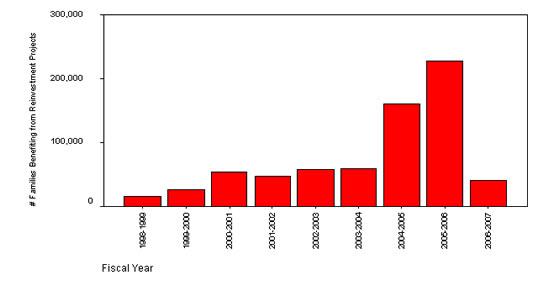

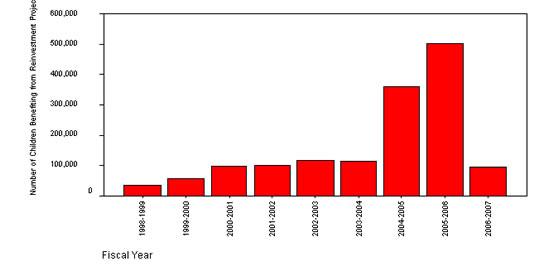

Scarcity of Meaningful Outcomes Data: Reporting requirements for the program result in very little meaningful outcomes data. Reporting is done annually and normally reports are on outputs only, such as numbers of participants and activities undertaken. Reporting is subject to over-counting of participating families: the same family or child can be counted numerous times if participating in several programs.

One Case Study community has educational outcomes data: One case study community, Walpole Island First Nation (Bkejwanong) applied much of its NCBR budget to school-based initiatives at the local elementary school, (based on assessed needs of students) such as individualized speech and art therapy for trauma and behavioural problems; a hot breakfast and lunch program; tutoring programs; purchase of sports equipment; and field trips for students. The school has improved EQAO scores as outcomes data.[Note 2]

Attribution of Outcomes is Extremely Difficult: Overall, attribution of outcomes for NCBR projects is extremely difficult, as the projects are often integrated with other programs, and "alleviation of poverty" is a complex, long-term and multifaceted outcome that would be attributed to many interacting factors.

National Child Benefit Reinvestment Program Recommendations

- Initiate a formal discussion with First Nations organizations and INAC regional staff on the most effective way to address reporting issues so that meaningful outcomes can be measured;

- Recommend to regions that they adopt a management regime similar to Saskatchewan region, which does the following:

- Outlines clear expectations;

- Sets targets in collaboration with First Nations;

- Communicates the intent of NCBR;

- Provide project proposal support.

- Revise reporting mechanisms to avoid multiple counting of program participants.

Assisted Living Program Findings

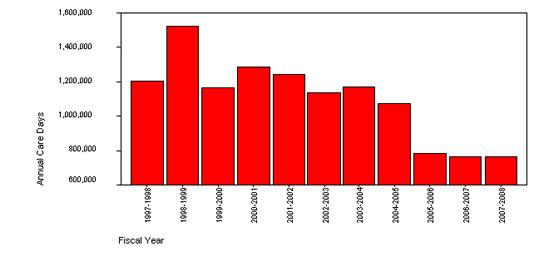

The Program is of Vital Relevance in Communities: The evaluation found that AL services being delivered in communities are meeting a real need and are highly valued by community members and AL end-users alike, as a means of assisting the elderly and disabled to remain in their homes and have an improved quality of life. Aboriginal health and demographic trends indicate that need for the program will rapidly increase in the near future.

Significant Gaps in Services: Service gaps noted by the evaluation include:

- Children's AL needs are not being met by the program. While the program authority for children's special needs for Assisted Living has been in place since 2003, no funding has accompanied this authority. Evaluators were told that in some cases, parents are giving Child and Family Services custody of their children so that assisted living services can be accessed off reserve.

- In most jurisdictions, needs of the developmentally disabled or brain-injured are not covered on-reserve.

- None of the communities visited had foster care or group home facilities. Only about 1% of the AL service profile is foster care.

- Supportive housing that would allow the frail elderly to "age in place" is not provided under the AL program

- Respite care, although covered under program authorities, is seldom provided. None of the case study communities reported providing respite care for family caregivers.

- After-hours and week end needs of clients are generally not being met.

Integration with FNIHCC at Community Level: Community visits showed that, at the community level, the in-home AL services, in their regional variations, are de facto integrated with Health Canada's First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC) at the service delivery, if not the funding, level. This may be due in part, to lack of a service delivery funding component, but is most likely the practical and common sense solution devised by First Nations service providers to efficiently meet client needs. The requirements of double reporting and keeping funding separate are reported as onerous in some cases.

Desire for Elderly to "Age in Place": Community visits showed a desire in most communities for institutional care or other higher levels of care alternatives that will allow the frail elderly to "age in place." Families and communities, as well as the clients themselves, reported the impacts of losing elders to off-reserve locations when they require higher levels of care than can be provided by the present AL in-home component. This finding was supported by opinions of the expert panel on assisted living, who noted this as a general trend in provincial programming.

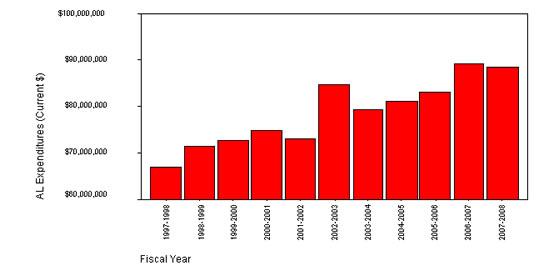

Funding Insufficient to Meet Needs: Funding is capped at 2% growth, and is not sufficient to meet the needs of either the in-home or institutional component of the program. Institutions need more funds for wages in particular. The funding formula relies too heavily on population rates and not on defined community needs.

Human Resource Challenges: One of the key findings of the evaluation is that the program is critically short of staff at the community level. Existing staff are noted as dedicated, but in danger of stress and burnout. Wages are not at par with off-reserve professional counterparts, making recruitment and retention of staff difficult.

Assessment of Outcomes Challenging: The program does not have an evaluation framework with defined outcome indicators. While supporting clients to "functional independence" is a program objective, the term is neither defined nor does it have supporting indicators. Even with such a framework, attribution of outcomes would require assessments according to a standard assessment tool, and would still be difficult in light of the complexity of interacting factors related to functional independence. More refined indicators would make attribution more achievable.

Assisted Living Program Recommendations

- Continue the initiative to devolve the funding and authority for the in-home component to the FNIHCC program;

- Secure Treasury Board funding for children's AL services, to resource the program authority in place since 2003;

- Coordinate discussions at the Federal / Provincial / Territorial and First Nations level to address other AL service gaps, resolve jurisdictional issues and develop an integrated approach to a full continuum of care model;

- Fund community-based AL needs assessments and use the information as a basis for reviewing current funding levels.

1.0 Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

1.1 Purpose and Structure of the Report

This report provides a synthesis and analysis of all the data collected from all the lines of evidence used in this evaluation project.

This report is structured as follows:

- Section 1.0: Introduction and Background to the Evaluation;

- Section 2.0: Evaluation Methodology;

- Section 3.0: Income Assistance Program Evaluation Findings;

- Section 4.0: NCBR Program Evaluation Findings; and,

- Section 5.0: Assisted Living Program Evaluation Findings.

Each section that discusses findings of a particular program (i.e., Sections 3 through 5) provide a description of performance measurement, program effectiveness, program impacts, and conclusions and recommendations specific to that program.

1.2 Objectives of the Current Evaluation

INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of Audit and Evaluation Sector (AES) contracted evaluations of the IA and NCBR programs in December 2007 while the AL program completed its own program-led review in November 2007. Upon review of the evaluation reports, the Treasury Board noted that it requires additional evaluation work be conducted on these programs in order to provide information about the "continued relevance, effectiveness and impact of the three programs" (Statement of Work, p. 1).

Accordingly, Audit and Evaluation Sector has committed to conducting follow-up impact evaluations of the IA, NCBR and AL programs, focused on an assessment of the impact of these programs on their end-users and assessing the programs' effectiveness with respect to their current program objectives. For the sake of cost effectiveness, a single evaluation of the three programs was conducted simultaneously.

The objectives of the current evaluation of the IA, NCBR and AL programs are:

- To report on the integrity / reliability of program data by conducting a review of the data collection capacity within the three programs;

- To assess program effectiveness with respect to the achievement of current program objectives; and,

- To assess the impact the programs are having on end-users.

1.3 Background to the Social Programs

This section of the report contains a brief background of the Income Assistance, National Child Benefit Reinvestment, and Assisted Living programs.

1.3.1 Income Assistance

Program Authorities and Objectives

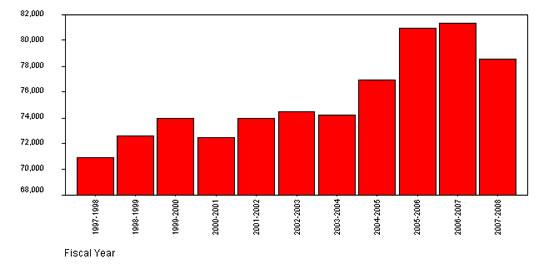

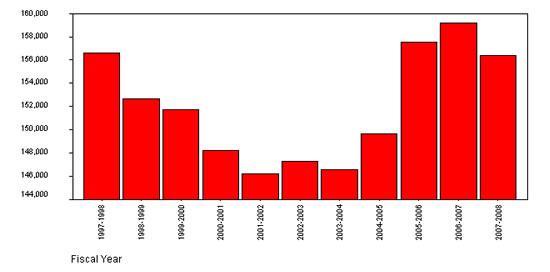

In terms of total expenditures, Income Assistance (IA) program is the largest of INAC's Social Development Programs and is the fourth largest welfare program in Canada. In 2006-2007, IA provided basic services to approximately 150,000 individuals in 630 First Nation (FN) communities.

The program authority for the IA program comes from a decision of Treasury Board. INAC is required to provide social assistance benefits comparable to those provided to other Canadian citizens in the respective provinces. Following Cabinet's approval of the general parameters of the program, a submission is made to Treasury Board outlining how funding is to be spent.[Note 3]

The program's objectives are to: 'provide support for the basic and special assistance needs of indigent residents of First Nation reserves and their dependants'[Note 4] (in the case of contributions), 'provide financial assistance to meet basic daily living requirements as per program terms and conditions'[Note 5] (in the case of grants), and to 'provide support for eligible FN individuals to receive pre-employment training, support and / or other active measures.'[Note 6]

The program attempts to meet these objectives through providing funds for basic needs, and increasingly in recent years, assisting recipients to address barriers to employment. Jurisdictions such as Ontario and Alberta have implemented Active Measures programs that are integrated with social assistance. Specifically, the income assistance program in Ontario ("Ontario Works") is geared to active measures (the "employment assistance" component); Alberta's program also has a strong active measures component, as does British Columbia, through it's "Training Employment Support Initiative" (TESI) which allows communities to set up programs for members on social assistance in order to develop the skills to enter vocational training, educational programs, or employment.[Note 7] The First Nations programs in these regions are delivering active measures programming to varying degrees, as determined by their capacity and supports available to do so.

The four main funding components of the IA program are:

- 'Basic needs - financial assistance to cover food, clothing and shelter;

- Special needs - financial assistance for special needs allowances for goods and services that are essential to the physical and social well-being of an IA client but not included as items of basic needs, such as special diets, etc.;

- Pre-employment supports - assistance may be provided to support activities that may include counselling and life skills, training in essential skills, transfers of income assistance entitlements to training and work experience projects; and

- Service delivery - funding provided to First Nations administrators such as Tribal Councils, Chief and Council or the host province / territory to cover service delivery.'[Note 8]

The IA program's expected results are:

- 'The alleviation of hardship;

- The maintenance of functional independence on reserve to standards of the reference province or territory; and,

- Greater self-sufficiency for First Nation individuals and communities.'[Note 9]

Generally speaking, there are two types of generic funding arrangements used with First Nations that have not entered into their own self-government agreements, Comprehensive Funding Agreements (CFAs), which are 1-year in duration, contain programs funded through contributions, and have a component of flexible transfer payments and grants; and Canada / First Nations Funding Agreements (CFNFAs), which are block-funding agreements for up to 5 years and can include funding from other federal departments.[Note 10]

Currently 81,000 recipients and 159,000 beneficiaries are supported through the Income Assistance program across the country. In 2008-2009, IA had projected expenditures / operating budget of $696.6 million, with an anticipated annual increase of approximately 2% each year until 2012 – 2013.[Note 11]

The program's current policy is to provide IA services comparable to those in the provinces; accordingly, the various regions attempt to mirror rate changes in their jurisdictions, but are not always able to mirror types and levels of service. Aside from funding the program, INAC provides policy guidance and compliance monitoring.

In total, 18% of the existing IA program budget is dedicated to meeting basic needs of shelter (shelter allowance).[Note 12] Shelter Allowance (SA) is made available by each provincial government in Canada to individuals of low-income, experiencing poverty, or on social assistance. Available funds to address shelter needs vary across Canada and, in some communities, may only be accessed by those holding a rental agreement.

Regional Differences

In most regions, INAC provides funds directly to First Nations or Tribal Councils, who in turn deliver the program to eligible recipients; although there are regional variations to this model. In Ontario, the program is the responsibility of the province but is delivered by First Nations delivery agents due to the Memorandum of Agreement Respecting Welfare Programs for Indians (often referred to as the "1965 agreement") between the Government of Canada and Ontario. Under the 1965 agreement, the province assumed responsibility for providing the income assistance services to the 110 First Nations in Ontario, while INAC funds the provincial programs on-reserve. In Ontario, First Nations are the effective delivery agents for IA. INAC pays the "municipal" share (20% benefits, 50% administration costs), direct to the First nations. The province funds the provincial share (80% benefits, 50% of the administration costs) to deliver IA to recipients "normally resident on reserve"[Note 13] and the province then charges these costs back to INAC. The result is that INAC reimburses the province approximately 93% of the IA costs, as per the 1965 agreement.

A "second level" of service is also provided to First Nations in Quebec, Manitoba, British Columbia, and Ontario, which helps provide tools and support to First Nation communities. In Quebec, it is coordinated by First Nations and is not funded by INAC. In British Columbia, second level service is provided by the First Nations Social Development Society, a First-Nations run group that works closely with INAC regional staff. In Manitoba, INAC funds Tribal Councils as second level service delivery agents: their role is to provide "on the ground" support for administration. Ontario is currently funding a pilot project at 19 sites in which higher levels of administration funding are provided to "second level" entities, either tribal councils or groups of First Nations; the final evaluation of this pilot is forthcoming within the year.

1.3.2 National Child Benefit Reinvestment

Program Authorities and Objectives

The National Child Benefit Reinvestment (NCBR) is a component of Human Resources and Social Development Canada's (HRSDC) National Child Benefit (NCB) initiative. The NCB is a federal/provincial/territorial initiative an initiative under the Social Union Framework Agreement that is aimed at seeking solutions to child poverty; promoting attachment to the workforce; and achieving a greater degree of harmonization of programs. INAC's National Child Benefit Reinvestment (NCBR) program is an on-reserve counterpart to HRSDC's off-reserve NCBR administered by INAC through an Interdepartmental Letter of Agreement with HRSDC which was implemented in 1998 as a federal / provincial / territorial initiative, uses funds derived through a complex process of offsets from IA/NCBS savings.

The overall NCB initiative is coordinated through HRSDC; INAC's NCBR component is funded through Treasury Board (Vote 15 – Grants and Contributions).The NCBR program may operate under agreements made with a province, a territory, or a First Nation. The agreements may take several different forms including: MOUs between INAC and the province / territory / First Nation; bilateral agreements between INAC and the province / territory / First Nation; and ad hoc joint working relationships between INAC and First Nation authorities.[Note 14]

The program's objectives, in terms of its indigent residents on-reserve are: 'to help prevent and reduce the depth of child poverty, to provide incentives to work by ensuring that low income families with children will always be better off as a result of working, and to reduce overlap and duplication through the simplified administration of benefits for children.'[Note 15]

The program attempts to meet these objectives through the provision of funds to address interests in the five following areas:

- 'Childcare - Programs that enhance child care facilities to enable more low-income families to access space for their children;

- Child Nutrition - Programs to improve the health and well-being of children by giving them nutritious meals in school and nutritional education for their parents. This activity includes the delivery of food hampers for low-income families;

- Support to Parents - Programs to help parents give their children a sound start in life, including training in parenting skills and drop-in centres;

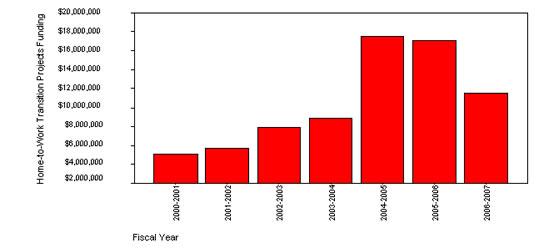

- Home-to-Work Transition - Programs intended to improve employment prospects, such as skills development and summer work projects for youth; and

- Cultural Enrichment - A broad category to teach traditional culture, provide peer and family support groups and bring together community elders, children and youth.'[Note 16]

The NCBR program's expected result is, 'by increasing income and employment support to all low-income families on reserve and streamlining government programs, low income families will recognize increases in children's health and development, increase in school readiness and ability to learn, and parents will fare better in the labour market, achieve a greater degree of financial independence for themselves and their children and participate more fully in their communities and Canadian society.'[Note 17]

INAC's NCBR program is project-based and proposal-driven. First Nations communities apply for funding for programs which fall under one or more of the following five activity areas: Childcare, child nutrition, supports to parents, home-to-work transition and cultural enrichment (described above). NCBR projects vary broadly in size and scope ranging from diapers for families in crisis to job counselling and training programs.

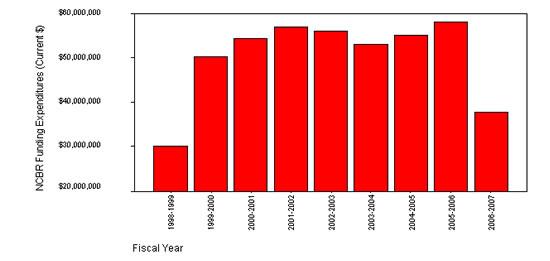

The flow of funding moves from Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) headquarters through to the regions, who in turn fund First Nations community projects based on submitted project proposals, although there are regional variations to the model. In general, First Nations have a great deal of flexibility in the spending of NCBR funds, within the parameters defined by their regionally-approved proposal. In 2008-2009 the NCBR program received $51.4 million in grants and contributions.

Regional Differences

There are differences in how the program is delivered across Canada; for example, the program is not delivered in the provinces of Manitoba, New Brunswick or Newfoundland and Labrador. Some provinces elect to have the NCB supplement go directly to families on reserve in addition to their IA benefits, rather than recover and reinvest the savings through NCBR programming.

1.3.3 Assisted Living

Program Authorities and Objectives

INAC's AL program (formerly Adult Care) provides support for the tasks of daily living to persons on-reserve with chronic illnesses and disabilities that restrict their functional independence.[Note 18]

The Assisted Living (AL) program is implemented under a separate policy authority and funding authority. These authorities are derived from Cabinet and the Treasury Board respectively.[Note 19]

The program's objective is 'provide social support programs which meet the special needs of infirm, chronically ill and disabled persons at standards reasonably comparable to the relevant province / territory of residence.'[Note 20]

The major components of the AL program are:

- In-home Care: Non-medical personal care (e.g. washing hair, preparing meals, housekeeping); at present this represents 58%[Note 21] of the service profile.

- Foster Care, which is comprised of supervision and care in a family setting; at present this represents less than 1%[Note 22] of the service profile; and

- Institutional Care: which provides Type I and Type II care in institutions. There are currently 32[Note 23] personal care homes (PCHs) on reserve across the country. If clients must go off reserve to access this type of care, INAC funds the care through reimbursement to the province. At present, this represents approximately 38%[Note 24] of the AL service profile. In the case of British Columbia, when a person is eligible and assessed at up to Intermediate Care level III, the Region funds the First Nations who have clients in institutions. The First Nations' administrating authority, in British Columbia, funds the comfort allowances and, in some cases, the user fees for clients in institutions through Basic, Social Assistance. Shelter is paid while a person is in temporary residential palliative care.

The AL program's expected results are:

- 'The alleviation of hardship;

- The maintenance of functional independence on reserve to standards of the reference province or territory; and,

- Greater self-sufficiency for First Nation individuals and communities.'[Note 25]

The AL budget also funds the institutional care of those individuals who must go off-reserve for this service. In 2008-2009, the AL expenditures / operating budget of $82.8 million, with an anticipated annual increase of approximately 2% each year until 2012-2013.[Note 26]

INAC's current involvement in AL primarily involves providing funding to First Nations, who in turn deliver non-medical assisted living programs and services to eligible community members. Health Canada, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch's First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC) provide medical and nursing care. The INAC and Health Canada programs are a part of a continuum of care and attempt to avoid duplication of services.

Regional Differences

There are variations across the country in the way that the AL program is established, implemented, and the programs / initiatives they fund (e.g. some regions fund Community Living[Note 27] while other do not). In general, the program is funded through contribution agreements and delivered by First Nations.

In Saskatchewan, there are instances where First Nations deliver AL services and other occasions where INAC delivers services. For example, INAC has a "paylist" of clients living off-reserve who are funded. Also, in Saskatchewan, residents on-reserve who need institutional care are paid by INAC to live in institutions off-reserve.

In Ontario, the Home Care component of the AL program (called "Homemakers") is a provincial responsibility (based on the 1965 Agreement). The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is responsible for program administration, and INAC reimburses the province through a funding formula; for institutional care, the institutions bill INAC directly each month. In Ontario, INAC subsidizes the gap between what low income persons can pay and the cost of the care for non-medical in-home care. This is an income-tested program (i.e. means test). In general, the provinces are further ahead in service provision than INAC. Ontario, however, is a unique case in terms of comparability, following the 1965 agreement; other regions are having difficulty keeping up with the level of provincial services.

In general, the provinces fund construction (e.g., for Personal Care Home facilities) for licensed institutions on-reserve, although there was a twenty year moratorium on such building that has only recently been lifted. Alberta and New Brunswick, however, do not provide funding for institution construction, or the Institutional Care component (i.e., Personal Care Homes) of the AL program.

2.0 Evaluation Methodology

This evaluation project was conducted through a series of activities:

- Development of the evaluation framework and methodology;

- Preliminary consultations;

- Document and literature review;

- Administrative and financial data review;

- Expert panels and key informant interviews; and,

- Case studies.

Each particular set of activities is briefly described in the following subsections.

2.1 Development of the Evaluation Framework and Methodology

This evaluation focused on the following five primary review issues:

- Data Collection & Performance Data System Adequacy - what type and quantity of program data is collected; are current indicators relevant; and is the current data collection system capacity adequate to measure program performance against intended outcomes?

- Relevance - do the programs continue to be consistent with departmental and government-wide priorities, and do they realistically address actual needs?

- Effectiveness - are the programs being administered and delivered in the most efficient and effective manner possible?

- Impact on End-Users- What impacts are the programs having on program recipients, and are these consistent with intended program outcomes?

- Cost-Effectiveness - are appropriate and efficient means being used to achieve outcomes, relative to alternative design and delivery approaches?[Note 28]

These issues formed the foundation for the framework for the evaluation.

For each review issue, one or more questions were developed that could be applied to several or all of the programs being evaluated. For each question, performance indicators and evaluation activities were identified. This series of questions, performance indicators and evaluation activities formed the framework for the evaluation. The framework formed the basis of the detailed methodology for the evaluation.

2.2 Preliminary Consultations

At the outset of the evaluation of the three projects, the evaluation team consulted with INAC headquarters and regional representatives (identified as preliminary consultation participants). A total of 13 preliminary interviews were conducted by the evaluation team, including 6 from INAC headquarters, one from each INAC Regional office (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia), as well as a consultant. The individuals consulted included those belonging to INAC's Evaluation branch, social program policy analysts, senior statistical officers, and managers of program funding and program operations.

The purpose of the preliminary consultations was to:

- Identify key documents, literature, and data sources;

- Identify key Informants;

- Identify Case Study Communities;

- Determine adequacy of data collection;

- Identify local / community contact to facilitate with applying end-user surveys; and

- Obtain high-level insight into program(s) successes and limitations.

The preliminary consultation activity began with the evaluation team identifying key INAC staff, in consultation with the client, along with contact information with each identified participant. The evaluation team developed an invitation letter, questionnaire, interview guide and interview compilation template prior to conducting the preliminary consultations. The evaluation team then contacted each participant to schedule and interview, and conducted the interviews at the agreed upon date. All interview data were entered into the client-approved interview compilation template.

2.3 Document and Literature Review

2.3.1 Document Review

The document review activity was designed to review a range of documents to gain an understanding of program objectives, performance measurement frameworks, performance of programs as assessed in program reports, previous audits and evaluations; and comparative programs delivered at the provincial level.

In the course of this activity, the evaluation team collected documents (either hard or electronic copies) either provided by – or identified by – the client and preliminary consultation participants, as well as relevant documents identified on the Internet. The evaluation team entered the document review findings into the client-approved document review template and upon further analysis, produced a document review report.

Documents consulted included program manuals, reports and reporting guides, program terms and conditions and other program-related documents; RMAFS/RBAFS; Annual Reports, previous evaluations and studies, and AG reports. Primary attention was paid to those documents that were provided by or identified by the preliminary contacts interviewed. The document review process provided another line of evidence for the evaluation and assisted the evaluation team in understanding the specifics about each of the three INAC social programs and how they are implemented in different provinces.

2.3.2 Literature Review

The evaluation team conducted a review of limited domestic and international literature to gain an understanding of the state of knowledge and key issues related to the three programs, particularly in terms of relevance. The evaluation team members, based on their knowledge of the field and in consultation with INAC's Evaluation Manager, developed a list of literature sources for review, with a focus on those sources which helped to frame the team's investigation of the three projects. The literature review provided another line of evidence for the evaluation.

The literature review process involved Internet searches for relevant literature, obtaining literature identified during the preliminary consultations, and entering the literature review findings into the client-approved literature review template. Based on the findings, a literature review report was produced.

2.4 Administrative and Financial Data Review

2.4.1 Administrative Data Review

The administrative data review was conducted at the national, regional and community levels (the latter was conducted as part of the case study methodology, described below). Administrative data was reviewed to provide information on program outputs and outcomes, budgets, the type of data being collected and what it is able to say about impacts; the extent to which program objectives are being met; and the level of consistency of data across regions.

The Administrative Review for the three programs was carried out with the assistance of our primary contact in this area at headquarters level, and with the regional INAC staff responsible for data reporting, coordinated via the Senior Evaluation Manager and the Audit and Evaluation Coordinators in the Regions. The evaluation team members worked directly with these staff members to gather and review the relevant social program data.

The types of data reviewed included:

- National roll-ups of regional level data;

- First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payments (FNITP) and Recipient Reporting Guide;

- Annual Reports;

- Monthly Reports;

- Quarterly Strategic Outcomes;

- Annual Audits of Program Expenditures;

The administrative data findings were entered in the client-approved data collection template.

2.4.2 Financial Data Review

The financial data review included an examination of program budgets, variance reports, contribution agreements, and year-end reports from partner organizations: these are all valuable sources of information on the financial management of programs.

The administrative and financial data review was conducted at two different stages in this assignment: initially, as a review of the initial information available, followed by a review of other documents / databases available at INAC Headquarters, Regional Offices and in the Case Study communities visited.

The financial data findings were entered in the client-approved data collection template, and synthesized, in combination with the administrative data, into a report.

2.5 Expert Panels and Key Informant Interviews

2.5.1 Expert Panels

Two expert panels were conducted in December 2008: one panel focused on the Assisted Living Program, and included experts in home care and assisted living from national, provincial and Aboriginal organization levels. The Income Assistance/NCBR panel was comprised of academic and service provider experts from the national, provincial and Aboriginal organizational levels.

Groups represented included:

- Representatives from Aboriginal organizations (national and provincial);

- Provincial government staff from linked/comparable program areas and Ministries;

- Representatives from linked social development programs such as First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care, HRSDC / AHRDA;

- Specialists in Disability / Assisted Living issues, Income Assistance, and the National Child Benefit Reinvestment programs;

- Specialists on Child Poverty; and

- Academic specialists on social assistance best practices.

The Expert Panels were intended to provide expertise and insight related to the current state of knowledge in the social assistance and back-to-work fields, with respect to the IA, NCBR, and AL programs specifically. The goal of the expert panels was to address questions pertaining to program relevance, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

The evaluation team identified a preliminary list or relevant experts, in consultation with the client, and collected contact information on the experts.

The evaluation team conducted 2 Expert Panels, each comprised of approximately 3-5 experts. One panel addressed the topic of Assisted Living services and the other the topic of social assistance and active measures, and the NCBR program. The rationale for the approach of grouping the NCBR and IA programs has to do with the notion that the NCBR and IA are closely linked in terms of objectives and funding source. The expert panel sessions averaged approximately 2.5 hours in length: some members participated by teleconference and some in-person. A total of 9 experts participated in the expert panels (5 AL experts and 4 social assistance / active measures and NCBR experts).

The findings of the Expert Panel discussions were synthesized into an Expert Panel and Key Informant Report.

2.5.2 Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted during the period of October – December 2008 and included both IA, NCBR, and AL program stakeholders and non-stakeholders; examples of non-stakeholders include program managers in comparable provincial program areas. Key Informants included representatives of the following roles:

- INAC national and regional program managers and staff;

- Provincial government staff from linked / comparable program areas;

- Tribal Council/ Nation or First Nations Health Directors; and

- Directors of Personal Care Homes.

The objective of the key informant interviews was to insight on data collection and performance data system adequacy; program relevance; program effectiveness; and the programs' impact on end-users.

Key informants were identified by the preliminary consultation participants. The evaluation team submitted the list of key informants to the client for approval.

Wherever possible, interviews were conducted in person; those who were either unavailable at the time that the evaluation team was in the region or was located outside the Ottawa area or Case Study community were interviewed by phone. A total of seventeen key informant interviews were conducted.

Interview findings were summarized and synthesized into a separate report.

2.6 Case Studies

The rationale for the case study approach was to spend a concentrated amount of time (2-3 days) in each of ten communities as a way of maximizing data collection. During this time a number of data collection methods were employed to gather as much information about program impacts as possible in the allotted time.

A Case Study methodology allows for "depth" of data analysis at the expense of breadth. Rather than administer a large national survey that would likely yield slim results, a Case Study methodology increased the possibilities of retrieving meaningful data, allowing the team to interact with program administrators, program users, service providers, and community members at large; provided for access to program files on site; and allowed the evaluators to make direct observations on the delivery of the program.

Preliminary consultations resulted in the identification of a possible list of communities; final selection of the sample was achieved through the assistance of regional INAC staff. The list revised as several selected communities decline to participate. For each region, "first choice" communities and "back-up" communities were identified.

The identification of these prospective communities was guided by the following selection criteria:

- The communities, where possible have all three programs being evaluated;

- Accessibility (how open the community is to outsiders);

- The communities are appropriately represented in terms of location, remoteness, size, economic circumstances, success and hardships;

- Both CFNA and CFA funding arrangements are represented; and.

- The program data will be comparable, where possible.

- Two case studies done in each of B.C. and Manitoba because of the number of First Nations and the number of residents in First Nations in each of those regions.

When conducting case studies in Aboriginal communities, it is essential that the purpose of the evaluation, evaluation activities being conducted, and types of community stakeholders to be involved in the evaluation are clearly communicated to both the community leadership and – assuming the leadership (Chief and Council) are supportive – to the community members as a whole. Initial contact with each selected community was in the form of an introductory letter sent by INAC to the Chief and Council of the community. This was followed by phone calls to key IA contact persons in the community by the evaluation team.

A total of ten case study communities were finally selected and conducted (see Table 1).

| Case Study Community Name | Date Case Study Community Visit was Undertaken |

|---|---|

| Eskasoni First Nation (Atlantic Region) | Week of November 10, 2008 |

| Walpole Island First Nation (Ontario Region) | Week of November 17, 2008 |

| Thunderchild First Nation (Saskatchewan Region) | Week of November 17, 2008 |

| Opaskwayak Cree Nation (Manitoba Region) | Week of November 24, 2008 |

| Gitanyow First Nation (B.C. Region) | Week of December 1, 2008 |

| Chehalis First Nation/Sto:lo Nation (B.C. Region) | Week of December 8, 2008 |

| Skownan First Nation (Manitoba Region) | Week of December 8, 2008 |

| Moose Cree First Nation (Ontario Region) | Week of December 8, 2008 |

| Beaver Lake Cree Nation (Alberta Region) | Week of December 15, 2008 |

| Gesgapegiag First Nation (Quebec Region) | Week of December 15, 2008 |

2.6.1 Methodology for Carrying Out Case Study Community Visits

The evaluation team visited the 10 case study communities between the weeks of November 10 and December 15, 2008. A team of two evaluators participated in each community visit: each team had a minimum of one (and in most cases, two) senior evaluators with extensive experience in conducting consultations in First Nation communities. The evaluation team spent a total of approximately 50 person days conducting community visits.

During the community visits, the following data collection methods were used:

- Service Provider Interviews (Staff and Administrators);

- Program file review;

- Focus Groups with end-users of IA and NCBR;

- Survey of AL end-users; and

- Community survey of a targeted sample of residents / IA recipients.

In the course of the ten community case study visits, the evaluation team conducted a total of:

- 77 interviews with administration/community service providers;

- 181 surveys with community members;

- 8 focus groups involving a total of 78 participants;

- 32 surveys with AL end-users;

- 1 survey with an NCBR end-user; and

- Collected and reviewed 129 documents / data sources.

When travelling to regional sites for case studies, evaluators conducted in-person interviews with regional INAC staff in most regions; Saskatchewan and Quebec interviews were conducted by telephone, and a site visit was not completed in Ontario due to restrictions of time and staff availability.

A key aspect of the case study methodology was the hiring of a local research coordinator/assistant to assist in administration of community door-to-door survey; coordination of the end-user focus group; end-user surveys of AL program users; and translation (when necessary). Local research coordinator/assistants were successfully employed in 5 of the case study communities; in another community, social development staff provided the supporting role that the research coordinator/assistant would normally provide. The services provided by the local research coordinators/assistants (where available) greatly assisted in ensuring that the maximum number of community members participated in the surveys and focus groups.

Another key aspect of the project methodology was flexibility and adapting to the particular circumstances of each community during the case study visit. In communities where no local research coordinator/assistant was available, the evaluation team conducted the surveys and focus groups. Further, the evaluation team often relied on the advice of the First Nations office staff regarding methods for maximizing community participation.

In some communities, the IA/NCBR end users surveys were conducted by approaching recipients at the welfare office as they collected their cheques; in other communities, the approach used was going door-to-door with the local research assistant; and in some communities, a combination of both approaches was successfully employed. In one community, additional surveys were conducted by the local research coordinator/assistant following the community visit by the evaluation team – these additional surveys were emailed to the evaluation team. For the AL end user survey, in most communities the evaluator accompanied the home care coordinator, home care nurse, or home support worker to client homes; in some communities, AL end users were also surveyed in public meeting places (e.g., local shopping mall).

Given the fact that several of the community visits were shortly prior to Christmas (a time of year that is very demanding on First Nations office staff) and/or shortly following a death in the community (which usually results in low community willingness to participate in consultation activities), circumstances were not always favourable for maximizing community participation; nevertheless a robust community sample was achieved.

For each case study community, a separate case study report was produced, which synthesized the findings from all data collection methods used in the community visit.

3.0 Income Assistance Program Evaluation Findings

3.1 Performance Measurement

Evaluators requested national, regional, and community level IA administrative and financial program data for a ten-year period, from 1997/1998 to 2007/2008. Requested data included the number of clients accessing the program, clients' characteristics, number of staff delivering the program, program expenditures and services by component, funding arrangement, employment creation, and welfare dependency rate.

3.1.1 Performance Measurement Framework

Table 2 below outlines the data reporting system for each of the three programs based on the Recipient Reporting Guide (RRG)[Note 29] and feedback from preliminary consultations. The table identifies and links each of the programs to its corresponding reports, funding agreements, data collection and report preparation body, report audience, reporting period, and the data being reported (by output and outcome).

| Data Collection Instrument Title | Applicable Funding Agreement | Who Collects Data and Prepares Report | Audience | Reporting Period | Type of Data To Be Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income Assistance Annual Summary Report | CFNFA/CFA[Note 30] | First Nations/ Region / HQ | HQ/Region | Annual | Mostly output indicators |

| Income Assistance Annual Report | CFNFA | First Nations / Region | Region | Annual | Mostly output indicators |

| Income Assistance Monthly Report | CFA | First Nations | Region | Monthly | Mostly output indicators |

| The People Strategic Outcome Quarterly Report |

CFA/CFNFA | Region | Region/HQ | Quarterly | Mostly output indicators |

| Audit report | CFA CFNFA | Audit and Evaluation Canada Audit and Evaluation Canada | Region Region | Every year (B.C., ATL) to 3 years (Quebec) At the beginning of the agreement or in the 5th year if the agreement is being renegotiated. There is no audit if the agreement is extended | Analysis of compliance of program or project to eligibility rules and conformity to laws and rules |

| Ad hoc program/financial reviews | CFA | Region | Region | Every 6 months (Quebec) or ad hoc (B.C.) | Analysis of compliance of program or project to eligibility rules and conformity to laws and rules |

| National Reporting Guide | CFA/CFNFA | First Nations / Region / HQ | First Nations / Region / HQ | The Recipient Reporting Guide (RRG) is a reference manual for INAC's program reporting requirements to assist recipients in complying with their specific funding agreements | |

| The First Nations and Inuit Transfer payments (FNITP) | First Nations / Region / HQ | First Nations / Region / HQ | Set by HQ | FNITP is a system that collects and tracks required information for FN and the INAC regions |

3.1.2 IA Data Gaps

The data seen in Table 3 below represents, according to both the RRG and what was heard in the preliminary consultations, the IA output and outcome data INAC ideally intends to collect annually.

| DataType[Note 31] | Annual Data Collected | Monthly Data Collected | Quarterly Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outputs |

|

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

|

In order to comment on the adequacy of performance data it is necessary to determine what data is actually collected by the programs. In order to do this, administrative and financial data was gathered at the national, regional, and community levels for a ten-year period covering the years 1997/1998 through to 2007/2008. The data sought included the number of clients accessing the program, clients' characteristics, number of staff delivering the program, program expenditures and services by component, funding arrangement, employment creation, and welfare dependency rate.

National Level

A review of the national level IA data gaps showed that significant outcome indicators, which could speak to program success and overall performance, were missing. Salient outcome data gaps at the national level include:

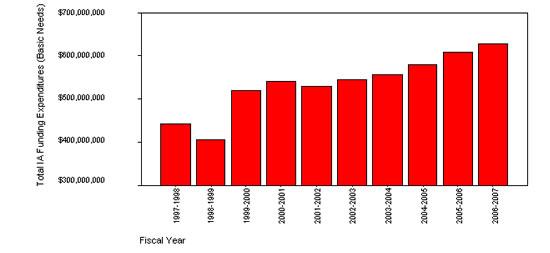

- Total IA Expenditures data (missing for the years 1997-2005);

- Number of Person Months of Employment Created (missing for years 1997-2000-); and

- Service Delivery expenditures (missing for the year 2007 – 2008).

Regional Level

Similar to the national level, a review of regional level data gaps showed that outcome indicators which could provide insight into program performance and success were missing. Salient data gaps at the regional level include:

- Total IA Funding Expenditures data (missing for the year 1997-2005);

- Number of Person Months of Employment Created and program expenditures data (missing the years of 1997-2005 for the regions British Columbia and Alberta, and1997-2006 for all other regions); and

- Service Delivery Expenditures data (missing for the year 2007-2008).

Community Level

The case study communities were asked to provide data reports that they generate at the community level. Those reports were reviewed and data (where it existed) was entered into the community level administrative and financial data review templates. Data gaps were then identified for each community. Given the difference in the range and level of data provided by each community, the data gaps are different for each community.[Note 32]

Salient data gaps at the community level include:

- Total IA Expenditures (missing for the years of 1997-2008 for all communities); and

- Number of Person Months of Employment Created (missing for the years of 1997-2003 for Opaskwayak, for the years 1997-2008 for Eskasoni and Gitanyow, and for the years of 1997-2007 for all other communities).

3.1.3 Ability of Data to Measure Outcomes

Meaningful Indicators not Used

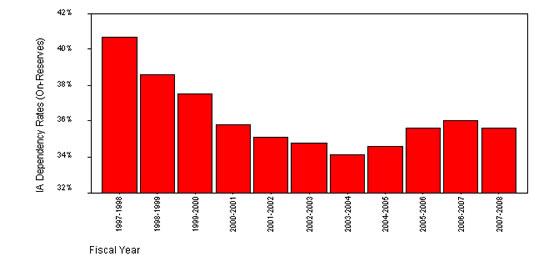

The program is unable to adequately and consistently measure meaningful outcomes. The chief reason for this is that indicators that would measure meaningful outcomes have not been developed and systematically used to direct data collection. Data that is collected is almost exclusively on outputs, rather than outcomes that measure program effectiveness. One of the exceptions to this is dependency rates; however, they are a rough measure. The information behind why dependency rates are rising or falling is not captured. If, for example, welfare dependency rates have fallen in a region, the program has no way of knowing the elements of this – whether former recipients have become permanently employed, or no longer meet eligibility requirements, have moved, or any other determining factors. In this regard, one regional staff member remarked that "We've lost track of what we need to measure and why. We don't know enough about the clients."

Data Gaps

Data gaps pose a challenge to assessing program performance and success at all levels (national, regional, and community) and hinder the ability to determine whether program outcomes are being achieved. INAC has data about income assistance expenditures and dependency rates; however, missing data on expenditures, welfare dependency, and employment created makes it difficult to determine whether the investment of income assistance dollars facilitates the movement off of social assistance programs.

3.1.4 Consistency and Comparability of Data

- Depending on the type of funding agreement, First Nations report either monthly or annually;

- Eligibility criteria and rates differ between INAC and provinces / territories;

- There is no common data platform. In some regions data is system-generated; for example in Quebec and Saskatchewan. Other regions may use other forms of reporting such as a reporting template;

- There is no consistent mechanism used for transmitting reports to the regions (i.e. some communities fax handwritten reports into the regional offices); and

- Employment creation is computed on a cumulative basis (i.e. spells of employment are added together across many individuals). Consequently, it is not possible to assess the number of days of full-time versus part-time employment created; nor is it possible to associate employment status with a particular recipient over time.

Frequency of reporting is linked to the type of funding agreement in place. 'The Comprehensive Funding Arrangement (CFA) is a program-budgeted funding agreement that INAC enters into with recipients for a one year duration.'[Note 33] This type of agreement requires regions to report monthly; whereas, the Canada / First Nations Funding Agreement (CFNFA), which is a block-budgeted funding agreement that INAC enters into with First Nations and Tribal Councils for a five year duration, requires much less frequent reporting.[Note 34] Accordingly, the data varies within regions according to funding agreement type. Almost the entire Atlantic region is funded under a CFNFA agreement which may account for the scarcity of data from that region.

3.1.5 Reporting Capacity

This section outlines evaluation findings with respect to the capacity of staff and systems to adequately report on the program.

National

There are a number of capacity issues at Headquarters that challenge the ability to measure outcomes:

- High staff turnover leads to a loss of corporate/institutional knowledge, and leads to quality control issues;

- Insufficient and inappropriately trained staff can compromise things such as follow up on public-private partnerships;

- There is a need for an appropriate data collection and inputting system. At present data needs to be entered manually (transposed) which increases the probability of errors; and

- System platforms change frequently.

Regional

Regions are lacking in staff and expertise in data management and analysis. In addition, regions are currently understaffed which compromises the level of detail applied to the work (i.e. carrying out comprehensive reviews reports), and hinders the region's ability to participate in national program meetings and other such activities.

Regional staff indicated frustration by the low level of feedback from Headquarters on reports they submit; this impedes their ability to plan programs based on evidence. Staff did not indicate whether this applied to specific reports, or all reports they submit.

Community

During the case study visits, program administrators were asked to provide program reports to the evaluation team. Of the 10 communities visited, 70% did not provide the evaluation team with program reports. The reasons for not providing these reports were as follows:

- Though communities had completed data reports (which they had sent to their regional INAC office) these reports were filed away and were not easily accessible at the time of the community case study visits (mentioned by 28.6% of communities who did not provide the team with program reports);

- INAC regional offices had already received the requested reports from the communities; therefore, it was recommended that the evaluation team contact the regional offices directly for the documents (mentioned by 57.1% of communities who did not provide the team with program reports).

3.2 Program Effectiveness

The evaluation aimed to determine how effective the program is in achieving its stated objectives to "alleviate hardship; maintain functional independence; and achieve levels of well-being reasonably comparable to the standards of the province or territory of residence."[Note 35] In doing so, the evaluation framework focused on questions of access; on the alignment of programs with program objectives; and on comparability of the programs with best practice.

3.2.1 Access to Services

INAC's Income Assistance program at the regional level is required, according to the program principles outlined in the National Manual, to provide income assistance to those "ordinarily resident on a reserve," "at standards reasonably comparable to the reference province or territory of residence."[Note 36] Exceptions to this are Ontario[Note 37] and Alberta, where the province, not INAC, dictates the terms and conditions of the program and INAC simply reimburses the province for these expenditures.

The program is not explicitly directed to enforce the same eligibility requirements as those employed by the province of reference, and the application of these is therefore inconsistent from one First Nation to another and one region to another. The IA Program Evaluation completed in 2007 noted that many First Nations are not enforcing the same eligibility requirements as their provincial counterpart,[Note 38] and some key informants in this evaluation concur on that point. It was emphasized that the region does not have the capacity to ensure that eligibility requirements are being followed by First Nations.

Overall, IA is accessible to eligible recipients on reserve, and there is a high level of awareness of the program and benefits available. Indeed, in most of the communities surveyed, residents expressed a concern that young people are too readily choosing welfare as an option as soon as they are able to qualify at age eighteen, rather than entering the work force or pursuing higher education.

The current evaluation did not find that community members were expressing concerns with being able to access Income Assistance. Evaluators found that the perception of inequitable access was expressed by some IA recipients in focus groups; not in terms of basic needs support, but discretionary funds for "special needs" such as replacement household appliances or one-time grants for children's sports equipment; or, gaining access to scarce employment opportunities through the First Nations. In these cases, recipients felt that IA staff members or First Nations Councils were showing favouritism to some residents over others, or that their needs were simply not being considered a priority.

3.2.2 Linkages / Integration with Complementary Programs

There are two main linkages at the federal level between INAC and Health Canada (providing support for addictions) and Human Resources and Social Development Canada (which provide training for IA recipients).

Many communities have developed liaisons with employment officers to benefit IA recipients. For example, Chehalis, B.C. has Employment Services that operate various programs including:

- Aboriginal Alternative Learning Program (funded by AHRDA), which receives Social Assistance referrals, identifies learning deficiencies and remediation tools;

- Structure of Intellect Program, which stimulates clients to use both halves of their brain;

- A computer-based program that develops numeracy and computer skills;

- Adult literacy skills;

- Reading program that works on improving memory skills; and,

- On-call jobs in the community (e.g., fishing, clearing brush).

There are linkages with AHRDA holders for employment and training programming (schools, tuition, employability skills training, and links to employment). Manitoba is operating in partnership with "Fire Spirit", a Winnipeg-based business that is helping First Nations assess job readiness and skill levels of residents, and then directing employment seekers to appropriate resources.

First Nation communities in BC have access to three programs to assist Social Assistance recipients make a transition to work: the Work Opportunity Program (WOP); the Training and Employment Support Initiative (TESI); and Aboriginal SA Recipient Employment Training (ASARET). However, the ASARET program was stopped because it contravened the Canadian Training Act, while the WOP was the main transition to work instrument for only one year. The main program accessed by SA recipients on-reserve is TESI: however, less than 5% of the unemployed, but employable, population on reserve accesses the program.

3.2.3 Service Gaps or Overlap

Basic needs assistance is being provided in all the communities surveyed, and the majority of respondents felt that there were not community members who needed IA but were not receiving it. In some communities there are programs that provide for basic needs of elders, but this does not constitute an overlap in service, as IA is not provided to those over 65.

Apparent service gaps exist in supports to finding and preparing for employment; 70.5% of community end-user IA respondents stated that they had never been assisted by a community program to find a job. Only a quarter of the community members who filled out the survey have been assisted; however, most jobs were short term.

INAC has had the program authority to implement active measures since 2003, but no increase in funding accompanied this change.[Note 39]

3.2.4 Comparability with Provincial Programs

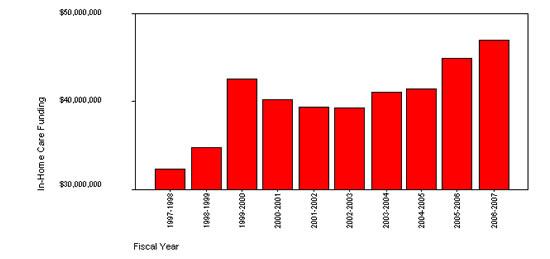

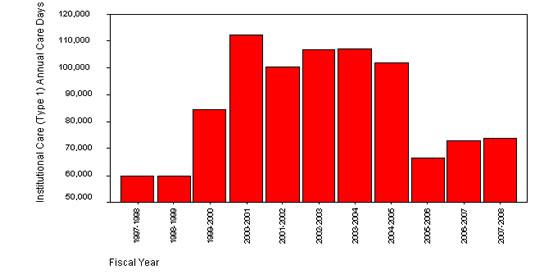

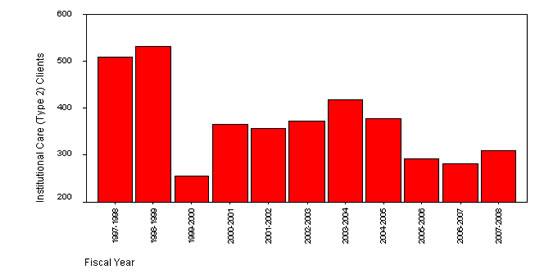

There is a problem of definition: how is "reasonably comparable" defined? INAC has a long way to go to reach comparability; they don't have the same aggregated budgets as the provinces. The result is that INAC regions are re-allocating funds from capital budget dollars in order to match provincial assistance rate increases. Likewise, when a province reduces the rates, INAC does likewise, whether or not that is the best response to needs on reserves.