Archived - Special Study on INAC's Funding Arrangements

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: December 2008

PDF Version (269 Kb, 73 pages)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- I. Introduction

- II. Overview of Findings

- III. Key Questions and Conclusions

- IV. Suggested Improvements

- Annex 1 - Statement of Work for the Special Study on Funding Arrangements

- Annex 2 - Case Study - Hospital and physician services grant to the governments of Northwest Territories and Nunavut

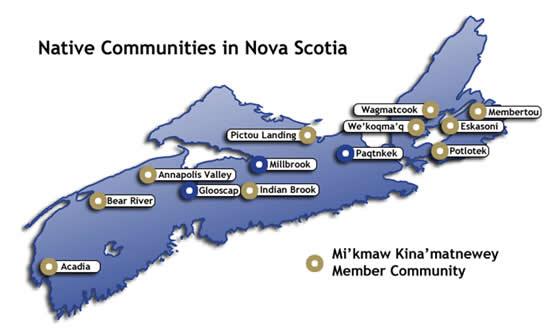

- Annex 3 - Case Study - Grant to Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey

Executive Summary

Background

The Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive in Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) commissioned the Institute On Governance to conduct a special study of INAC's funding arrangements and accountabilities to inform further research and action. The study focuses primarily on non self-governing First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Aboriginal organizations providing services to First Nations. It was conducted through a documentation and literature review (refer to separate document); discussions with officials, experts; and recipients; and case studies.

With the devolution of the delivery of programs and services from INAC to First Nations and Tribal Councils, new funding arrangements and funding authorities were adopted that were intended to provide increased flexibility to First Nations to respond to their own needs. The architecture of the current funding arrangements is complex and consists of:

- Funding authorities – grants, alternative funding arrangements (AFAs), flexible transfer payments (FTPs), and contributions.

- Funding arrangements – comprehensive funding arrangements (CFAs) comprised of a combination of grants, contributions and FTPs; DIAND First Nation Funding Arrangements (DFNFAs) comprised of grants, contributions, FTPs, and AFAs; Canada First Nation Funding Arrangements similar to DFNFAs except that they consolidate programs and funding from other government departments; and Self Government Financial Transfer Arrangements used exclusively for self-governing First Nations and therefore not part of this study.

- Program authorities defining the terms and conditions for providing funding under that authority. The major programs for a First Nation are social assistance, education, and capital facilities management.

Other Aboriginal organizations are funded through grants, contributions and FTPs and do not have access to AFAs. Single year or multi year comprehensive funding arrangements (CFAs or MCFAs) are primarily used for this group. There is an array of program authorities used.

Our investigations of the status of funding arrangements indicate that there has been no progression in terms of the movement of First Nations and Tribal Councils into block funding arrangements over the past ten years. There is a reluctance to move into more flexible arrangements or multi year agreements because of concerns about annual adjustments, particularly for income assistance and primary and secondary education.

There was no assessment conducted of the capacity of recipients with CFAs in our sample and no capacity building plans developed to guide their progression to more control over their funding. Intervention is focussed primarily on debt reduction and not on sustainable capacity building.

The other Aboriginal organizations in our sample had single year CFAs despite the long term and supportive nature of their relationship with INAC. There were significant delays in concluding agreements resulting in delays in payment and jeopardizing the organizations' ability to implement agreed upon projects or programs.

Appropriateness

Despite the centrality of funding arrangements to the Department and their importance in terms of INAC's relationship with First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Indian-administered organizations, we conclude that they are not appropriate. There is a lack of clarity about the overall objectives of the funding arrangements, a lack of coherence among programs and funding authorities that make up the arrangements, and no clear leadership at INAC Headquarters. There is limited engagement of the recipients. The movement of First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Indian-administered recipients towards increasingly responsive, flexible, innovative and self-sustained policies, programs or services is not being promoted.

Effectiveness

In terms of the effectiveness of funding arrangements in meeting INAC's policy and program objectives, there is very little information about what results are being achieved since most of the reporting relates to inputs, activities or outputs and very little about outcomes or results. Risk management, accountability and flexibility are not well balanced within the funding arrangements in terms of the amount of money involved, the nature of the program, or the capacity of the recipients.

In terms of risk management, there are only two funding arrangements for non self-governing First Nations and Tribal Councils despite the huge diversity of capacity and risks within these groups. Funding authorities are linked to the method of calculating the funding (formula-driven or fixed costs versus proposal-driven or variable costs) and not to the capacity of the recipient. Program authorities vary in terms of their approach to risk management. Often very small programs are monitored very closely whereas very large programs are monitored very loosely.

Similarly, single year CFAs and funding authorities are used with other Aboriginal organizations regardless of the nature of the relationship, the program being funded or the track record of the recipient. Some of these organizations were micro-managed whereas a more strategic approach was taken with others, but the differences seemed to be linked to differences in INAC's staff rather than differences in the capacity of the organizations.

An appropriate accountability framework needs to be in place to support strong accountability relationships based on clear roles and responsibilities, clear performance expectations, balanced expectations and capacities, credible reporting, and reasonable review and adjustment. Effective accountability is therefore not defined solely by funding arrangements. Our study indicated that accountability is not working well because there is inadequate reporting on performance; no serious informed review of the program information reported; and no appropriate program changes, incentives for good performance, or consequences for poor performance.

The accountability of First Nations to their members is a function of good governance practices. Having their own source of revenue increases the expectations of members and enhances their need to be accountable. Other Aboriginal organizations also had to balance expectations against the amount of funding available, and responsiveness against the terms and conditions of the funding. Both groups thought that INAC should be accountable to them for its performance in managing the funding relationship.

Funding arrangements were seen to be focussed on INAC's policies and programs and not those of the recipient. Flexibility was constrained by the amount of funding. Targeted interventions reduced flexibility further. And intervention eliminated all flexibility. Other Aboriginal organizations were further constrained by delays, holdbacks, stacking limits, and the inability to retain surpluses. For both groups, having access to other sources of revenue increased flexibility.

Efficiency

The administrative burden for some First Nations and Tribal Councils and most of the other Aboriginal organizations was onerous whereas for others it was considered to be manageable. The funding provided for management and administration was considered to be inadequate by all. In general, INAC's resources in the regions were focused more on following up on reports, compliance reviews and audits rather than preventive and proactive measures.

Views on the reporting burden also varied. There is not much difference between the reporting for First Nations and Tribal Councils under CFAs versus DFNFAs. The amount of reporting was not commensurate with the amount of the funding, and there was some duplication across reports. Of more concern to the First Nation and Tribal Council recipients was the value of the reports to INAC since they did not receive feedback. There was a lot of frustration in all three regions about INAC losing or misplacing reports and holding back funding.

There is little coordination of funding arrangements across the federal government, few CFNFAs, and widely varying terms and conditions across departments. We identified a number of constraints to interdepartmental coordination or harmonization.

Recommendations

This special study comes at an opportune time when INAC is undertaking a strategic review and a new transfer payment policy and directive have been issued by Treasury Board in response to the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grant and Contribution Programs. The new Transfer Payment Policy addresses some of the concerns we have raised in terms of risk management, flexibility, longer term funding, a results orientation, and the development of partnerships. An Aboriginal Cluster of federal departments has been created and INAC is expected to take the lead in this Cluster.

We make five recommendations to address the issues that we have raised:

- Clarify the objective of funding arrangements - to achieve better socio-economic outcomes in partnership with First Nations. This means a focus on results that should lead to enhanced accountability, improved performance and more realistic expectations.

- Appoint a departmental leader at the ADM level.

- Develop partnerships at the national and regional level with First Nations.

- Revise the architecture of funding arrangements to increase the diversity, reduce the complexity of programs, utilize multi year arrangements, and set service standards for INAC.

- Assess recipients and develop and support a capacity building strategy designed to continuously improve their performance.

Further research is suggested related to risk assessment, results based reporting, own source revenue, communities in crisis, and capital funding.

I. Introduction

A. Background

Over the past three decades, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) has increasingly devolved program design, administration and delivery directly to First Nations, territorial governments, Inuit communities and organizations, and other Aboriginal organizations - with a corresponding change in funding arrangements. INAC has also promoted self-government for those First Nations that wish to pursue it and the corresponding design of new funding models.

The funding regime is complex and the programming obligations and reporting requirements can become tangled and onerous with the involvement of other departments beyond INAC. A number of observers within and outside of INAC have called for a fundamental change in how the federal government understands, designs, manages and accounts for its funding, particularly to First Nations but also to other organizations.

INAC's Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive commissioned the Institute On Governance (IOG) to conduct a special study of INAC's funding arrangements and accountabilities. This special study will inform further research and action aimed at improving funding arrangement design, instrument choice, accountability provisions and their effectiveness, efficiency and appropriateness in furtherance of broad government policy objectives.

B. Statement of Work

The objectives of the special study are two-fold:

- To determine to what extent the funding arrangements available to the department in furtherance of its and the government's policy objectives respecting First Nations, Aboriginal peoples and Northerners are:

- appropriate for the purposes for which they are used;

- effective in achieving the policy outcomes targeted; and

- efficient both administratively (vertically) and as government (not just INAC) policy instruments (horizontally).

- To establish to what extent the accountability provisions in these arrangements are appropriate and effective in achieving the accountability and reporting needs of funding recipients (to local stakeholders) and those of the Minister (to Parliament and Canadians).

The funding arrangements targeted by the study are those currently in use, excluding self-government financial transfer agreements, treaty related payments, payments in relation to comprehensive land claims, and payments to individuals. The arrangements include contribution agreements (CAs) [Note 1], comprehensive funding arrangements (CFAs), DIAND First Nation Funding Arrangements or Canada First Nations Funding Arrangements (DFNFAs/CFNFAs) and grants.

Two important issues that arise in discussions around funding arrangements that were not included in the Statement of Work are the amount and adequacy of funding provided, and the allocation of the funding among recipients or across programs. Both of these subjects are questions of policy that exist independently of the means used to deliver funding. They affect funding arrangements themselves however and we therefore cannot avoid referring to them as part of the analysis.

A description of each funding arrangement is provided in the next section of this report. The complete Statement of Work is provided in Annex 1.

C. Note on Recipients

The Statement of Work refers to funding arrangements used with First Nations, Aboriginal peoples and Northerners. These recipient groups differ greatly in the way INAC relates to them differences which are reflected in the funding arrangements used and the evolution to date of these funding arrangements.

- First Nations and Tribal Councils - After the 1980 Penner Report, INAC strove to move Funding Arrangements for First Nations governments along a continuum towards increasing flexibility, block funding, and accountability requirements oriented more towards results than a detailed accounting for inputs and outputs. This evolution was intended to be consistent with the government's policy objectives to prepare First Nations for transition to self government. The same general approach applied to Tribal Councils (groupings of First Nations). For that reason, only FNs and TCs had access to multi-year block funding authorities.

- To non-First Nations on behalf of First Nations - A substantial amount of funding flows directly from INAC to other organizations in order to fund the delivery of programs and services to First Nations. Recipients include providers of child and family services, elementary and secondary education, post-secondary education, cultural programs, economic development programs, and other services to First Nations. Recipients may or may not be Indian-administered and can include provincial ministries or agencies such as school boards. There is also funding that flows to First Nations representative organizations and to national Aboriginal professional, technical and support organizations. Funds are generally provided through Comprehensive Funding Arrangements.

- Northern First Nations - With respect to Northerners, First Nations located in Yukon and Northwest Territories (NWT) have "traditionally" received more of their services through the respective territorial governments than is the case south of 600. However, their funding arrangements with INAC resemble those of southern First Nations, though somewhat less in scope, especially in NWT. It should be noted that 11 of 14 Yukon First Nations are covered by self-government funding arrangements and that one NWT First Nation has a self-government agreement and several others have agreements-in-principle.

- Inuit - With respect to Inuit, the primary funding relationship is different from that applying to First Nations. Programs and services for Inuit have generally been provided by the provinces or territories that they inhabit. As land claims have been settled, the major Inuit groups (Inuvialuit, Nunavik, Nunavut and Nunatsiavut) have moved to quite different degrees and types of self-government and funding relationships (and funding arrangements), in each case still involving the provincial or territorial governments. Because self-government agreements and comprehensive land claims were excluded from this study, most of these arrangements are also excluded.

- Other Aboriginal groups - INAC's relationships with other Aboriginal groups stems from its recent acquisition of the Office of the Federal Interlocutor (OFI) with its funding relationships with organizations representing Métis, urban Indians, and non-status Indians; and from its acquisition of Aboriginal Business Canada. These relationships and the resulting arrangements are quite program-specific.

In terms of assessing the various funding arrangements, these differences among recipients are critical. With respect to INAC's major "business" of funding non self-governing "Indian Act First Nations and preparing these for eventual self-government, funding arrangements are significant policy instruments. In fact, the 2008-2009 INAC Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP) acknowledges the importance of funding arrangements:

"A significant amount of the department's mandate is derived from policy decisions and program practices that have developed over the years; it is framed by judicial decisions with direct policy implications for the department; and it is structured by funding arrangements or formal agreements with First Nations and/or provincial or territorial governments." (emphasis added)

This is not the case with respect to funding arrangements with INAC's other recipient groups. For that reason, this report focuses primarily on First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Aboriginal organizations (primarily Indian-administered) providing services to First Nations. More information related to Inuit; Métis, urban Indian, and non-status Indian organizations and peoples; and Northerners is contained in the documentation and literature review.

D. Approach and Methodology

General Approach

The study was conducted in three phases:

Phase 1 – Work planning

Phase 2 – Research and data collection

Phase 3 – Analysis and reporting

Four lines of evidence were used:

- a documentation and literature review;

- discussions with officials from INAC and other federal departments and with experts;

- discussions with a randomly selected and broadly representative sample of First Nations, Tribal Councils, and other Aboriginal organizations in the selected regions of British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Quebec; and

- case studies.

The research was conducted from August to November 2008. Members of the project team traveled to the three regions in September and October in order to review files, conduct interviews, and visit recipients where feasible. Interviews were also conducted in the National Capital Region during that period.

Documentation and Literature Review

The final documentation and literature review is attached as a separate document. It is based on previous research, evaluations, reports and available literature on the subject of fiscal transfers, funding arrangements and accountability. It was used in its draft form to brief the project team and the Project Authority, and to highlight key issues for investigation during the study. Relevant information will be referred to throughout this report.

Discussions with INAC and other federal officials and with experts

We conducted interviews with officials from INAC Headquarter who are involved with funding arrangements, governance, strategic policy, programs, audit and evaluation, regional operations, and Inuit relations. We also conducted interviews with the directors of funding services, funding service officers, and education and social program officials in the three regions.

We held discussions with relevant officials in First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC) and Public Safety Canada about their funding arrangements and their views of INAC's funding arrangements. We held a meeting with the Treasury Board Secretariat near the end of the data collection phase in order to discuss the new Transfer Payment Policy which came into effect on 1 October 2008 and their views of the implications of that new policy for INAC.

Throughout the data collection and analysis phase, we spoke to five experts with knowledge and experience of INAC's policy, programming, funding and accountability arrangements in order to test out certain findings and conclusions.

Discussions with First Nations, Tribal Councils, and Other Aboriginal Organizations

We randomly selected a sample of 30 First Nations to be interviewed across the three regions. The sample was broadly representative of various factors – amount of funding, size, type of funding arrangement, geographic zone, environmental zone, community index of wellbeing, etc. We also randomly selected a sample of 10 Tribal Councils across the three regions that was broadly representative in terms of amount of funding and type of funding arrangement and balanced with the FN selection in terms of geographic areas within each region.

We also selected a sample of 24 other Aboriginal organizations that were funded through the three regions or by INAC Headquarters. The organizations funded by Headquarters included governance, land management, economic development, culture and northern research organizations. The organizations funded through the three Regional Offices included Indian-administered child and family service agencies, culture and education centres, economic development corporations, Indian-administered post secondary institutions, self-governing First Nations with CFAs, and sectoral agreement holders. Certain Aboriginal organizations (Aboriginal business financial institutions, Métis, urban Indian and Non-Status Indian organizations, and national and provincial/territorial Aboriginal representative organizations) were excluded from the sample because of previous or current evaluations.

The original number of recipient interviews that were planned and the actual number that were conducted are presented in the following table:

| Recipient | Planned Number | Actual Number |

|---|---|---|

| First Nations | 30 | 15 |

| British Columbia | 12 | 6 |

| Saskatchewan | 12 | 5 |

| Quebec | 6 | 4 |

| Tribal Councils | 10 | 8 |

| British Columbia | 4 | 2 |

| Saskatchewan | 4 | 4 |

| Quebec | 2 | 2 |

| Other Aboriginal Organizations | 24 | 18 |

| Headquarters | 10 | 8 |

| British Columbia | 5 | 3 |

| Saskatchewan | 6 | 4 |

| Quebec | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 64 | 41 |

As the table indicates, we had the most difficulty setting up the interviews with First Nations but we were able to get additional perspectives on the funding of First Nations through our interviews with Tribal Councils and other Aboriginal organizations.

Case studies

A total of 8 case studies were conducted across Canada. The breakdown of the case studies across the different funding authorities or arrangements is as follows:

- Grants to the Government of the North West Territories and the Government of Nunavut for the health care of Indians and Inuit (refer to Annex 2);

- Grants to the Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey, an institution established by the Mi'kmaw Education Act of 1999 (refer to Annex 3).

- CFAs (3) with 1 Tribal Council in Quebec, 1 FN in BC, and 1 FN in Saskatchewan.

- CFNFAs (2) with 1 Tribal Council in Saskatchewan and 1 FN in Quebec.

- 1 CFA with an Aboriginal organization that provides services to First Nations.

The CFA and CFNFA case studies were drawn from the sample of FNs, TCs and other Aboriginal organizations. The case studies involved a more extensive set of interviews and a file review. The results will be used to illustrate certain points in more detail in this report.

E. Purpose and Outline of Report

This report summarizes and analyzes the findings from the four lines of evidence and formulates conclusions and recommendations. It is organized into thee main sections:

Section I – Introduction – this section which provides details on the study and this report.

Section II – Overview of Findings – provides an overview of the development of funding arrangements, their components, current status, and trends in the three regions.

Section III – Key Questions and Conclusions – presents the findings and draws conclusions in terms of the key issues of the special study – appropriateness, effectiveness and efficiency.

Section IV – Recommendations – makes five main recommendations for improvements on the basis of the findings and conclusions.

II. Overview of Findings

This section is divided into three parts. In the first part we summarize the history of INAC's funding relationship with First Nations and previous reports on that relationship. In the second part we describe the architecture of funding authorities, funding arrangements and program authorities for First Nations and Tribal Councils and other Aboriginal organizations. And finally, in the third part we provide a status report on current funding arrangements and trends in the past decade.

A. A Brief History

By the 1980s, "devolution" was already well underway as INAC moved from direct delivery of most services on reserve to delivery through First Nations themselves using Contribution Agreements. Contributions were however perceived by First Nations as excessively burdensome and inflexible. Subsequent to the Penner Report on Indian Self-Government (1983), INAC obtained approval for other types of funding authority intended to increase First Nations' flexibility in program delivery and to reduce the administrative burden. Thus Alternative Funding Arrangements were approved in 1983 and Flexible Transfer Payments were approved in 1989. Funding Arrangements were also rationalized so that individual First Nations would have only one Funding Arrangement for all programs funded through INAC rather than a separate arrangement for each program.

As devolution became complete, the ongoing funding relationship as expressed in the Funding Arrangement became a critical feature of the relationship between Canada and individual First Nations. For most non self-governing First Nations, the annual Comprehensive Funding Arrangement (CFA) or multi-year DIAND or Canada First Nations Funding Arrangement (DFNFA/CFNFA) is the only formal signed agreement between Canada and the First Nation.

Coupled with substantial reductions in INAC staff over the period to 1994, INAC's role was very much reduced to that of a funding agency, with the greatest proportion of its funding transferred to First Nations for their program purposes.

Through the 1990s and more recently, the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), internal audits, evaluations, and Auditor General of Canada reports have continued to focus on the administrative and reporting burden associated with Funding Arrangements with non self-governing First Nations, even under the more modern flexible or alternative types of arrangements. These reports have also cited the problem of the proliferation of new programs or spending initiatives funded outside the flexible portion of a funding arrangement.

The most recent discussion of the subject was the December 2006 Report of the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grant and Contribution Programs. Concerns regarding grants and contributions are widespread across government, although INAC seems to be the most strongly criticized agency. The Treasury Board has responded by revising its Transfer Payment Policy and Directive in favour of a more flexible approach, which INAC will also have to address.

There is therefore a consistent story line from the Penner Report to the most recent report from the Blue Ribbon Panel. In spite of years of criticism on the one hand, and attempts to reform on the other, the major concerns about excessive and misdirected accountability and reporting requirements remain unresolved.

B. Architecture of Funding Arrangements

Funding arrangements are composed of general terms and conditions, funding authorities, and program authorities. This is what we call the architecture of funding arrangements. A description of the architecture for the two main recipient groups is outlined in further detail in the following sections.

First Nations and Tribal Councils

Funding Authorities

There are four types of funding authority used by INAC with decreasing levels of flexibility:[Note 2]

- Grant—a transfer payment which is not subject to being accounted for or normally subject to audit by the department, but for which eligibility and entitlement may be verified or for which the recipient may need to meet pre-conditions. The recipient may be required to report on results achieved.

An example is INAC's grant for band support funding (BSF) which assists band councils to meet the costs of local government and administration but which gives First Nation communities the flexibility to allocate funds according to their individual needs and priorities. Band councils submit an application form with data that is used to establish the funding level. Band councils also maintain budgets and accounts for BSF funds that are available to their members. AFA recipients must also include BSF funds in their audited financial statements [Note 3].

- Alternative funding arrangements (AFAs) provide five year funding and the flexibility to transfer funds across programs in addition to the ability to retain surpluses (and the responsibility for deficits) [Note 4]. According to the AFA authority, eligible First Nations and Tribal Councils can design programs and allocate funds to meet community needs and priorities provided that minimum program requirements are met. Budgets are set according to regional formulae and are supposed to be adjusted annually to ensure recipients are neither advantaged nor disadvantaged financially in relation to non-AFA recipients. First Nations and Tribal Councils wishing to enter into an arrangement under the AFA authority must meet various entry requirements as well as the requirements of individual program terms and conditions.

There are numerous programs and services to which AFA block funding applies. This includes contributions for land and estates management, for registration administration, for elementary and secondary education programs and services, for post-secondary education, for income assistance and assisted living, for National Child Benefit Reinvestment, for capital facilities and maintenance, for band support and tribal council funding, and for economic development.

- Flexible transfer payments are usually applied where funding is based on formulae or fixed costs. According to the FTP authority, FTP funding is distributed on a program basis with "a strong incentive for recipients to more effectively manage programs and services within the fixed budget" since any surpluses can be retained for use at the Council's discretion provided that minimum program requirements are met [Note 5]. Under an FTP, reporting requirements are supposed to assess program performance rather than how each dollar is spent.

Where the recipient is a First Nation, the authority requires that an accountability and management assessment be conducted by INAC before entering into a funding arrangement. The assessment is to be based on an accountability or management standard that is common to all levels of government in Canada. Following the assessment, INAC may work with the First Nation to prepare a management development plan to address any gaps identified. This management development plan is to be attached to and form a part of the FN's funding arrangement and be reviewed on an annual basis. (We did not find any evidence of an assessment having been done in the three regions for our sample of FNs with CFAs.)

FTP funding applies to a similar set of programs and services as AFA block funding, with the major exception of income assistance. The FTP funding authority also covers funding to a number of other Indian-administered and Aboriginal organizations which provide programs and services to First Nations.

- Contribution - a conditional transfer payment for a specified purpose that is subject to being accounted for and audited. If there is provision for advances to be paid, there is no provision for the retention or carry forward of surpluses at the end of the fiscal year. Contributions are usually used to fund proposals or reimburse variable costs such as income assistance.

Funding Arrangements

INAC has constructed its funding arrangements for First Nations and Tribal Councils using the four funding authorities as building blocks. The principal types of funding arrangements currently used are:

- Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (CFAs) – a combination of grants, contributions and FTPs as applicable to the various programs.

- DIAND First Nation Funding Arrangements (DFNFAs) – a five-year agreement for INAC funding which uses two streams: block funding using the AFA funding authority for those programs and services that are eligible; and targeted funding based on contribution or FTP authority for other programs. Canada First Nation Funding Arrangements (CFNFAs) are similar to DFNFAs except that they consolidate programs and funding from other government departments. Both DFNFAs and CFNFAs are also known as Flexible Transfer Arrangements (FTAs).

INAC's current policy [Note 6] provides for an assessment to be undertaken prior to signing a new or renewed DFNFA/CFNFA. The criteria for entry are:

- experience in administering programs

- sound organization for purposes of program management

- processes and procedures in place for program management and financial control

- mechanisms in place to support accountability

- in a sound financial position or if problems exist, have a plan in place which has been operating effectively over a six month period to remedy the problem

- a sufficiently detailed plan covering the duration of the agreement showing how the agreed-upon level of funding for the initial fiscal year will be administered and projected expenditures for each subsequent fiscal year.

The related guidelines provide further details on the assessment of human resources, financial and program management; and leadership and governance.

- Self Government Financial Transfer Arrangements (SGFTAs) – used exclusively with self-governing First Nations. These are multi-year grants covering all of the programs and services delivered under the relevant self-government agreement. Accountability to Canada is limited to annual audited financial statements and the extent of a First Nation's accountability to its members is specified in the First Nation's constitution. SGFTAs increasingly include provisions for Own Source Revenue and taxation, usually with off-set provisions that are phased in over a number of years.

There are no contribution agreements or multi year comprehensive funding arrangements used for FNs and TCs according to INAC's transfer payment system.

National models of CFAs and DFNFA/CFNFAs are reviewed and updated annually, along with an annual update of the Recipients' Reporting Guide (formerly called the First Nations' Reporting Guide). The models include, where applicable:

- General terms and conditions

- Accountability framework

- Program or service budgets, authorities and monthly expenditure plan

- Program and service delivery and reporting requirements

- Adjustment factors

- Schedule of reporting requirement due dates

- Management development plan (if available) – we did not see any MDPs attached to the CFAs that we reviewed for our case studies

- Remedial management plan (if applicable)

The accountability framework that is required includes not only financial accountability to INAC but also the development of a system of accountability to First Nation members in the case of a First Nation Council, or to member First Nations and their members in the case of Tribal Councils. This system is to include provisions for transparency, conflict of interest, benefits for elected and unelected senior officials, disclosure and redress.

INAC's funding arrangements with First Nations and Tribal Councils do not have an explicit hold back provision but funding may be withheld for non-receipt of annual audited financial statements or other reports.

The departmental authority for intervention is contained in the terms and conditions of both CFAs and DFNFA/CFNFAs. Instances of default where the Minister may intervene include the following:

- the terms and conditions of the funding arrangements are not being met;

- the auditor gives a denial of opinion or adverse opinion with respect to the financial statements of the recipient;

- the financial statements indicate that the recipient has incurred a cumulative deficit equivalent to eight (8) % or more of its total annual revenues; or

- the health, safety or welfare of FN members is being compromised.

There are three levels of intervention:

- Remedial Management Plan (RMP): when the recipient is willing and has the capacity to address and remedy the problem, a Remedial Management Plan is drawn up and implementation of the RMP is monitored.

- Co-management: when the recipient is willing but lacks the capacity to address or remedy the problem, a co-manager is appointed;

- Third Party: when the recipient is high risk and/or is unwilling to address or remedy the default, a Third Party Manager (TPM) is appointed by the Minister.

A new audit clause has been introduced into Model Funding Arrangements effective 2008/09. This clause permits the Minister(s), at any time during or up to five years after expiry of an agreement, to carry out audits or evaluations of the effectiveness of any of the programs and services funded under the Arrangement, or of the Council's management practices in relation to the Arrangement. This clause is in line with audit clauses found in the contribution agreements of other government departments.

Program Authorities

According to the Public Accounts 2007/08, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development operated with a total of 54 transfer payment program authorities. Of these, 12 were related primarily to the delivery of services by First Nations and Tribal Councils. The remaining 42 program authorities were related to self-government agreements or negotiations, claims settlements, treaty-related matters, other organizations, or individuals.

The program authorities for First Nations and Tribal Councils cover aspects of the ongoing governance and administration, education, social development, economic development, and capacity building of First Nations and Tribal Councils as well as targeted interventions in certain areas. Each program authority defines terms and conditions for providing funding under that authority and these terms and conditions are incorporated into funding arrangements to a greater or lesser extent. The terms and conditions include the objectives and results of the program, the accountability framework, the audit and evaluation framework, and the management control framework.

Financial reporting requirements are defined in the Year-end Reporting Handbook for First Nations, Tribal Councils and First Nation Political Organizations. This handbook covers general as well as program specific financial reporting and the reporting of all federal government funding. Program reporting requirements are defined in the Recipient Reporting Guide applicable to recipients funded under CFAs, CFNFAs and DFNFAs. This guide includes 67 separate reports - not all of which would be applicable to any one First Nation or Tribal Council. Many of the reports are applicable to both CFAs and DFNFA/CFNFAs. Most reports can be completed and submitted electronically through the FNITP and 175 First Nations are currently using this facility. There are plans to expand electronic reporting through FNITP to other First Nations over the next few years.

Illustrations

The following table provides an illustration of how the different funding authorities and program authorities come together within a comprehensive funding arrangement with a First Nation. This First Nation receives about $9.5 million annually from INAC and we have also included a breakdown of the budget under the CFA to illustrate certain points.

Illustration 1 - First Nation CFA

| Program or Service [Note 7] | Funding Authority | % Budget | Reports Required | Frequency/Due Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and Management | ||||

| Band support funding | Grant | 7.9% | ||

Band employee benefits

|

FTP Contribution | 1.3% |

|

30 April Annual 30 April |

| Registration & membership | FTP | 0.1% | ||

| Social Programs | ||||

| Income assistance basic needs | Contribution | 23.9% | IA Basic Needs Reports | Monthly |

| Income assistance service delivery | FTP | 0.9% | ||

| Income assistance special needs (2) | Contribution | 2.9% | Annual Report | Annual, end of April |

| National Child Benefit Re-Investment | Contribution | 6.4% | Annual Report | Annual, 31 May |

| Assisted Living | Contribution | 0.8% | Home Care Summary | Monthly |

| Family violence | FTP | 0.2% | Projects Report | Annual, 31 May |

| Education Programs | ||||

Band operated schools

|

Contribution FTP FTP |

22.9% |

|

Annual, Oct. 15 Annual, Oct. 15 |

Provincial

|

FTP Contribution |

0.7% |

|

Annual, Dec. 31 Annual, Dec. 31 Annual, Dec. 31 |

| Student support services (2) | FTP | 3.4% | No report required for transportation. | |

| Post secondary education | FTP | 8.3% |

|

Annual, Dec. 31 Annual, Dec. 31 Annual, Dec. 31 |

| Youth employment strategy (3) | Contribution | 0.7% |

|

Annual, 31 March Annual, 31 March (2), 15 Sept. (1) |

| Economic Development | ||||

| Community Economic Opportunities Program | Contribution | N/A | Project Status Report | Annual, 120 days after the end of the FY |

| Community Economic Development Program | FTP | N/A | Operational Plan Program Report |

Annual, Jan 15 Annual, 120 days after the end of the FY |

| Capital Programs | ||||

| Water and wastewater action plan | Contribution | < 0.1% | ||

Education, infrastructure and housing

|

FTP Contribution |

7.4% |

|

Annual, March 31 Annual, March 31 Annual, March 31 Annual, March 31 Annual, end of June |

| O & M of infrastructure and education assets and facilities (10) | FTP | 12.1% |

|

Annual, March 31 |

| Financial | ||||

| Financial Statements | Annual Audited Financial Statements | Annual End of July | ||

| Remedial Management Plan | Follow Up Submission | Quarterly | ||

Note: (#) indicates the number of budget line items under that item with the same funding authority – e.g. Income Assistance Special Needs consists of two budget line items, both of which are funded as a contribution.

As the table indicates, the major programs for a First Nation are social assistance, education in schools (either on reserve or off reserve in provincial schools), and capital facilities management. The breakdown of the funding varies somewhat depending on certain factors that are particular to the First Nation or the region.

The table also illustrates the number of components under each program with relatively small amounts of money. There is limited flexibility in terms of these components and separate reporting requirements. In addition, the funding may not be allocated at the beginning of the financial year - in this particular case, the CFA had been amended five times by October in order to add funding for proposal driven projects and capital projects or reallocations.

The table also indicates how different funding authorities are used for different program components. The largest contribution is for income assistance. The largest flexible transfer payment is for instructional services in education. Most of the reporting required is annual, with the exception of income assistance and assisted living.

The next table illustrates how the funding authorities and program authorities come together under a DFNFA with a First Nation. This First Nation receives about $4.8 million annually. It is more difficult to show the budget breakdown across the components because budgets are negotiated in the initial year and then adjusted annually at the same time as targeted interventions may be added or dropped. The budget figures in italics are therefore based on the initial budget, and the budget figures that are not in italicsare based on the 08/09 budget as of October 2008.

| Program or Service | Funding Authority | % 08/09 Budget | Reporting Requirements | Frequency/Due Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block Funding | 93.9% | |||

| Governance and Management | % 05/06 Budget | |||

| Maintenance of Band government systems | AFA | 12.4% |

|

On renewal On renewal |

| Registration & membership | AFA | 0.3% | None specified | |

| Social Development | ||||

| Provision of income assistance | AFA | 14.1% | Annual Report | Annual, May 31 |

| Provision of assisted living | AFA | 0.8% | Annual Report | Annual, May 31 |

| Education | ||||

| Provision of kindergarten, elementary and secondary education | AFA | 20.0% | Nominal Roll Education Staff Information | 15 Oct. 15 Oct. |

| Provision of post secondary education | AFA | 22.8% |

|

Annual, Dec. 31 Annual, Dec. 31 Annual, Dec. 31 |

| Economic Development | ||||

| Provision of programs relating to economic development | AFA | 0.9% | CEDO Operational Plan CEDO Report |

Annual, 15 Jan. Annual, 120 days after end of FY |

| Capital Programs | ||||

| Water & sewer capital and O&M | AFA | 17.5% |

|

Annual, 31 Mar Annual, 31 Mar Annual 31 Mar Region/Project dependant Annual, Mar 31 Project dependant |

| Housing | AFA | 4.1% | ||

| Targeted Funding | 6.1% | |||

| Governance and Management | ||||

| Professional & Institutional Development | FTP | 0.3% | Final Report | Annual, Mar 27 |

| Education | ||||

| Special Education - Band operated Schools | Contribution | 1.0% | Annual Report | Annual, May 15 |

| Special Education - Provincial Schools | Contribution | 0.3% | Annual Report | Annual, May 15 |

| Social Development | ||||

| Special Needs - Early Childhood Intervention Program | Contribution | 0.1% | Annual Report | Annual, 30 April |

| Assisted Living - Institutional Care | Contribution | 0.4% | Monthly Report | Monthly |

| Family Violence | FTP | <0.1% | Self-evaluation report | Annual |

| Youth Employment Strategy (3) | Contribution | 0.9% |

|

Annual, 31 March Annual, 31 March (2), 15 Sept. (1) |

| Land Management | ||||

| FN Land Management Initiative | FTP | 2.2% | None specified | |

| First Nation's Land Management | FTP | 0.5% | Summary report of land management transactions | Annual, 31 December of following year |

| Capital Programs | ||||

| Certified Operator Funding | FTP | 0.3% | None specified | |

| Financial and Funding | ||||

| Financial Statements | Annual, July 31 | |||

| Annual Return Management Report | Annual, within 90 day of FY end | |||

There is therefore more consolidation of programs and fewer components under the block funding. The reporting requirements are similar to CFAs with the exception of annual rather than monthly reporting for income assistance and assisted living. The Annual Return Management Report requires that the FN recipient attest to adherence to the minimum program requirements that are detailed in the report format.

There are also a number of targeted interventions that in this case add up to less than 10% of the total funding. This proportion may be understated however as targeted funding can be added over the course of the year. In another FN that we looked at, targeted funding was about one-third of the total funding provided by the year end. These targeted interventions each have their own program terms and conditions including reporting requirements.

It is more difficult to illustrate funding arrangements with Tribal Councils because they can provide a range of services and not all Tribal Councils provide all of the services. For example, some Tribal Councils only provide technical advisory services to FN members whereas other Tribal Councils may take on the administration of programs on behalf of their member First Nations. The following table therefore illustrates the potential programs and services that could be delivered through Tribal Councils and the related funding authorities under a CFA and under a DFNFA, without any budget breakdown.

| Program or Service | Funding Authority under a CFA | Funding Authority under a DFNFA | Reporting Requirements | Frequency/Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and Management | ||||

| TC Funding Program - Management & Administration | FTP | AFA | Annual Report | Annual, May 31 |

| TC Funding - Advisory Services | FTP | AFA | Annual Report | Annual, May 31 |

| Band Employee Benefits – statutory - non-statutory |

Contribution FTP |

AFA AFA |

Pension Plan Funding Report Funding Application List of Eligible Employees |

Annual (CFAs) or on renewal (DFNFAs), May 31 |

| Consultation & Policy Development | FTP | FTP | Annual Report | Annual, Set by region |

| Indian Management Development | FTP | FTP | Annual Report | Annual, Set by region |

| Education | ||||

| Education Second Level Advisory | FTP | AFA | Annual Report | Annual, May 15 |

| Special Education - Indirect | Contribution | Contribution | Annual Report for First Nation Regional Managing Organizations | Annual, July 30 |

| School Evaluations | FTP | FTP | TORs School Evaluation Report |

Once every 5 years 30 June |

| Teacher Upgrading | Contribution | Contribution | Final Activity Report | Annual, May 15 |

| New Paths | Contribution | Contribution | Final Project Report | Annual, May 15 |

| Capital Programs | ||||

| Band Asset Management Inventory System | FTP | AFA | Housing and Infrastructure Assets Report | Annual, Oct. 15 |

| Circuit Rider Water Operator Training | FTP | FTP |

|

Quarterly, by 20th of following month Annual, 90 days after FY end Annual, April 15 As conducted |

| Economic Development | ||||

| CEOP - direct and flow through | FTP | FTP | Project Status Report | Project Dependant |

| CEDO | FTP | AFA | Operational Plan Program Report | Annual, 15 Jan. Annual, 29 June |

| Social Development | ||||

| Youth Employment Strategy (3) | Contribution | Contribution |

|

Annual, 31 March Annual, 31 March (2), 15 Sept. (1) |

| Emergency Shelter | FTP | FTP | Annual Report | Annual, May 31 |

| Self Government Negotiations | ||||

| Self Government Negotiations | Contribution | Contribution | Progress Report | Project dependant |

| Financial and Funding | ||||

| Audited Financial Statements | Annual, 31 July | |||

| Annual Return Management Report (CFNFA/DFNFA only) | Annual, set by region | |||

As the table illustrates, there is still funding under a DFNFA that is provided under an FTP or contribution funding authority rather than an AFA authority for a number of programs or services. In our Tribal Council case studies, this amounted to about 10% of the total funding that the Tribal Council received.

The table also shows that there is little difference in the reporting requirements for DFNFA versus CFA TC recipients. All of the reports are annual except the Circuit Rider Water Training and the Youth Employment Strategy projects. The format for the Annual Return Management Report, attesting to meeting minimum program requirements, is the same as for FNs even though most of the programs are not applicable for TCs.

Other Aboriginal Organizations

Funding Authorities

There are three types of funding authority for recipients other than FNs and TCs – grants, flexible transfer payments and contributions. Alternative funding arrangements are not applicable to this group of recipients.

The FTP authority is the same as that for FNs and TCs except that an accountability and management assessment is not required before entering into the arrangement. FTPs apply to programs and services provided by Cultural Education Centres, Child and Family Service Agencies, post secondary institutions, the Indian Taxation Advisory Board, and the First Nations Land Management Resource Centre, among others. These organizations were included in our interview sample.

Funding Arrangements

The funding arrangements used by INAC for recipients other than First Nations and Tribal Councils are:

- Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (CFAs) - a combination of grants, contributions and flexible transfer payments as applicable to the programs, services or activities that are funded and/or the recipient. The agreement is for a single fiscal year.

- Multi Year Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (MCFAs) – multi year arrangements not to exceed five fiscal years that can include a combination of grants, contributions and flexible transfer payments. There is no provision for the carry forward of funds from one fiscal year to the next under these arrangements although there is provision for revising budgets.

- Grants, treaty related matters, and treaty loans – these arrangements are related to self government, comprehensive claims and other treaty related activities. The grants include our two case studies – the grant for Mi'kmaq education in Nova Scotia and the grants to the Governments of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut for health care of Indians and Inuit. Grants used to be provided to FN political organizations for core funding, but with the renewal of the authority in 2007/08, this funding is now provided as a contribution.

National models of CFAs and MCFAs are reviewed and updated annually and include the same sections as CFAs for FNs and TCs, although the content is different:

- general terms and conditions

- an accountability framework that primarily refers to financial accountability to INAC, conflict of interest, and financial disclosure

- program, service or activity budgets, authorities and monthly expenditure plan

- programs, services and activity delivery requirements and reporting requirements

- adjustment factors

- schedule of reporting requirement due dates

Because there is no requirement for an assessment of the administrative, accountability and management practices of the recipient prior to entering into the arrangement, there is no reference to a Management Development Plan in the national models.

Both CFA and MCFA models include a provision for the holdback of at least 10% of the total funding due to the recipient, including flexible transfer payments, until the submission of the required reports. (There is a holdback of 20% on the core funding of Aboriginal representative organizations.) In the case of MCFAs, this holdback is applicable to each Fiscal Year.

In the event that a recipient is in default under the arrangement, they may be required to develop a Remedial Management Plan, INAC may withhold funds, other action may be required or the arrangement may be terminated.

Program Authorities

According to the Public Accounts 2007/08, there were a total of 15 program authorities applicable to organizations other than FNs or TCs. Some of these program authorities relate to the delivery of services on reserve. Some Aboriginal organizations receive funding under special authorities such as:

- contributions to the First Nations Finance Authority to enhance good governance

- contributions under the Aboriginal Business Canada Program (previously under Industry Canada)

- contributions under the SchoolNet program to six regional organizations (previously under Industry Canada)

- contributions to the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation

- contributions to implement the First Nations Land Management Act

- the Federal Interlocutor's contribution programs for Métis and non status Indian organizations, the Urban Aboriginal Strategy and the Powley Initiative

- contributions to basic organizational capacity building of representative organizations.

It is not possible within the scope of this study to review all of these program terms and conditions. It is also not possible to provide an illustration of a funding arrangement to other Aboriginal organizations as they differ so greatly.

Having outlined the architecture of funding arrangements, we will now turn to a description of the current status of those funding arrangements nationally and an analysis of the trends in our three regions.

C. Status of Funding Arrangements

According to INAC's First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment (FNITP) system, there were a total of 2,115 funding agreements with organizations as of November 5, 2008 (refer to Table 2). Forty-one per cent of the agreements were with First Nations and Tribal Councils, and 59% with non First Nations and non Tribal Councils. First Nations and Tribal Councils however received more than 75% of the total funding provided through the agreements. This reinforces the point made previously that the funding of FNs and TCs is at the core of INAC's mandate.

| Type of Recipient | No. of Agreements | % Total Number | Total Allocation | % Total Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FN and TC | 862 | 40.8% | $3,602,321,991.34 | 75.2% |

| Non FN and Non TC | 1253 | 59.2% | $1,191,185,490.38 | 24.8% |

| TOTAL Organizations | 2115 | 100.0% | $4,793,507.481.72 | 100.0% |

First Nations and Tribal Councils

Of the total number of funding agreements with First Nations and Tribal Councils as of 5 November 2008, 19% were DFNFA/CFNFAs; 71% were CFAs; and 10% were other types of arrangements [Note 8]. Of the total funding to First Nations and Tribal Councils, however, DFNFA/CFNFAs accounted for 36% of the total – indicating that the arrangements tend to be with larger First Nations or Tribal Councils.

| Type of Agreement | No. of Agreements | % Total Number | Total Allocation | % Total Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFNFA/DFNFA | 165 | 19.1% | $1,289,177,022.17 | 35.8% |

| CFA | 610 | 70.8% | $1,975,654.341.30 | 54.8% |

| Other | 87 | 10.1% | $337,490,627.87 | 9.4% |

| TOTAL FN and TC Agreements | 862 | 100.0% | $3,602,321,991.34 | 100.0% |

By comparison, the 2005 Evaluation of AFAs and FTPs indicated that there were a total of 181 DFNFA/CFNFAs in 1995/96 and 182 DFNFA/CFNFAs in 2002/03 [Note 9]. There has not therefore been any progression of FNs and TCs nationally to more flexible arrangements over the past ten years – indeed, since 2002/03 there has actually been a decrease of roughly 10%.

Other agreements include 32 grant agreements, primarily to self-governing First Nations and Tribal Councils. One notable exception is the Miawpukek First Nation in Conne River, Newfoundland that is not self-governing but has received funding through a multi-year grant since its recognition as a First Nation in 1985.

The breakdown of DFNFA/CFNFAs by Region is presented in the following table. There is considerable variation across the regions but we are not able to explain it because we only dealt with three regions.

| Region | Total DFNFA/ CFNFAs | FN DFNFA/ CFNFAs | Total FNs in Region | % of FNs in Region with DFNFA/ CFNFA | TC DFNFA/ CFNFAs | Total TCs in Region | % of TCs in Region with DFNFA/ CFNFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 31 | 29 | 33 | 88% | 2 | 6 | 33% |

| Quebec | 17 | 17 | 39 | 44% | 0 | 7 | 0% |

| Ontario | 40 | 33 | 139 | 24% | 7 | 16 | 44% |

| Manitoba | 18 | 15 | 63 | 24% | 3 | 7 | 43% |

| Sask. | 13 | 12 | 70 | 17% | 1 | 9 | 11% |

| Alberta | 14 | 8 | 46 | 17% | 6 | 8 | 75% |

| BC | 24 | 22 | 198 | 11% | 2 | 27 | 7% |

| Total | 157 | 136 | 588 | 23% | 21 | 80 | 26% |

Regional officials in our three regions confirmed that after an initial movement of FNs and TCs into DFNFAs ten years ago, there has been little change. Few new FNs or TCs have moved into the block funding arrangements, few FNs or TCs have moved back into CFAs, and very few FNs or TCs have concluded self government agreements. Some FNs and TCs have entered into their "third generation" of a DFNFA – i.e. more than ten years under that type of arrangement.

There was great concern among FNs and TCs with DFNFAs that their annual adjustments did not cover increased costs or population increases, particularly for social assistance and education. There was a perception that they had been disadvantaged in terms of annual increases compared to FNs and TCs with CFAs. Efforts to use the "extenuating circumstances" clause in their FA to renegotiate amounts had not been successful. However, none of the FNs and TCs was considering moving back to a CFA because they appreciated the increased flexibility that the block funding provided. Many of the FNs and TCs with DFNFAs were in self-government negotiations – and had been for years. There was also a concern expressed that SGFTAs will provide less funding than a DFNFA, or that the underfunded DFNFA amounts will be used as the base for the SGA.

None of the FNs and only one of the TCs in our sample had a CFNFA. According to INAC Transfer Payments, there are a total of 26 CFNFAs nationally – almost all with First Nations.

Most FNs with CFAs that we interviewed were not interested in moving into another arrangement. Some would not qualify, others were comfortable with the discipline that their CFA gave them, and others did not understand what was required. Most were concerned about the ability of annual adjustments to accommodate price and volume increases and thought they were better off under a CFA. For the same reason, many were not interested in multi year arrangements. Tribal Councils were even less interested in moving to block funding because they did not perceive that there was any advantage in terms of increased flexibility or reduced reporting requirements.

In terms of the flexible transfer payments in the CFA, none of the FNs and TCs that we interviewed could recall that a management assessment had been done and there were no Management Development Plans in the CFAs that we looked at.

All of the FNs and TCs interviewed indicated that they had funding arrangements in place by the start of the fiscal year for most of their funding. Funding under proposal driven programs or targeted interventions was included at the beginning of the year or added over the course of the year as it became available or as application processes were completed.

Other Aboriginal Organizations

Of the total of 1,253 funding agreements with recipients other than First Nations and Tribal Councils as of November 5, 2008, 43% were CFAs; 51% were MCFAs, and 6% were other types of arrangements (predominantly grants). In terms of funding, however, CFAs accounted for 76% of the total, MCFAs for only 4%, and other arrangements for 20%.

| Type of Agreement | No. of Agreements | % Total Number | Total Allocation | % Total Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | 543 | 43.3% | $909,966,171.33 | 76.4% |

| MCFA | 633 | 50.5% | $48,863,819.00 | 4.1% |

| Other | 77 | 6.1% | $232,355,500.05 | 19.5% |

| TOTAL Other Than FN & TC Agreements | 1253 | 100.0% | $1,191,185,490.38 | 100.0% |

We looked at one grant to another Aboriginal organization (refer to Annex 3). The grant to Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey (MK) is provided in terms of the Mi'kmaq Education Act that transferred jurisdiction for education on reserve from the federal government to First Nations in Nova Scotia. Funding for education in the participating communities is channelled through MK and responsibility for capital replacement funding has been centralized under MK's management and control. Annual adjustments to the amount of the grant are based on the Consumer Price Index and increases in the nominal roll. Funding for new education programs is not channelled through the grant, but through a separate CFA so that the grant currently represents approximately 81% of MK's total funding and the balance is CFA funding. The participating communities and MK are required to report annually on their education programs and services and student enrolment, and to provide consolidated audited financial statements for MK and for all participating communities - all of which are publicly available.

There has only been a model for multi year CFAs in INAC in the last two years. Most of the MCFAs are with recipients funded through Aboriginal Business Canada and the Office of the Federal Interlocutor which had their own model arrangements.

All of the organizations in our interview sample had single year CFAs, even though all of them had been receiving funding over a number of years and were supporting the achievement of one of INAC's strategic outcomes. For example, education centres provide 2nd tier education services, cultural centres provide cultural resources, and professional associations support the professionalization of the First Nation public service. Other organizations were created through legislation or by a formal agreement, had developed five year plans and budgets, but received funding on an annual basis and through contributions or FTPs rather than grants.

We were told by INAC officials and recipients that the reluctance to take the risk of negotiating a multi-year agreement was due to:

- not knowing what reference levels would be in future years;

- not wanting to jeopardize the Minister's fiduciary and accountability responsibilities; or

- uncertainty about the future of funding for some of the organizations, e.g. SchoolNet.

In most cases, funding arrangements with other Aboriginal organizations were negotiated several months into the financial year, and payments were also delayed. We noticed a substantial increase nationally in the number of agreements and the amount of funding allocated between July and November 2008 (refer to Table 6). There was a 75% increase in the number of agreements with non FNs and non TCs, and a 57% increase in the amount of funding allocated through those agreements.

| Agreement Type | Number as of July 9, 2008 | Number as of November 5, 2008 | % Increase | Amount as of July 9, 2008 | Amount as of November 5, 2008 | % Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | 334 | 543 | 62.6% | $554,282,708.34 | $909,966,171.33 | 64.2% |

| MCFA | 326 | 633 | 94.2% | $24,256,047.00 | $48,863,819.00 | 101.5% |

| Other | 58 | 77 | 32.8% | $181,967,244.00 | $232,355,500.05 | 27.7% |

| Total | 718 | 1253 | 74.5% | $760,505,999.34 | $1,191,185,490.38 | 56.6% |

Intervention

According to an assessment of funding arrangements, of the 1,174 agreements in place with First Nations and Tribal Councils as of March 31, 2007, 84% required no intervention and of the remainder, only 18 or less than 2% required third party management.

| Total | No intervention required | Intervention required | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remedial management plan | Co-management | Third party management | New intervention requirement or expired intervention plan | |||

| Number | 1174 | 989 | 55 | 50 | 18 | 62 |

| Percent | 84.2% | 4.7% | 4.3% | 1.5% | 5.3% | |

Source: Funding Arrangements for First Nations Government Assessment and Alternative Models, Peter Gusen, February 2008, p. 21.

According to regional officials, the overwhelming reason for intervention is debt – there is an automatic trigger if the cumulative operating deficit reaches 8% or more of total operating revenues. Some recipients may progress from third party management to co-management to a remedial management plan and then fall back into debt again once they regain full management control over their expenditures.

In one of our CFA case studies that is currently under a Remedial Management Plan, the deficit was incurred over several years by all programs, particularly band based capital, band government, and education, which all have flexible funding. The social development basic needs program had also incurred a deficit despite being funded through a contribution. The Remedial Management Plan proposed to eliminate the deficit within five years through tighter controls on both INAC and non-INAC programs and monthly financial reporting. For the first three years of the plan, the targets for deficit reduction were exceeded but then the band slipped back because of a large housing project.

According to the regions, First Nations in third party management and co-management have been fairly consistent over the past ten years. A very few have been in third party management for more than a decade. In this case, the level of intervention is more likely to be due to governance problems or the failure to disclose consolidated financial statements. The FN pays for third party management from its band support funding but we were told that the cost never exceeds the amount provided.

Summary

The preceding status report indicates that there has been no progression in terms of the movement of FNs and TCs into block funding arrangements over the past ten years. There is a reluctance to move into more flexible arrangements or multi year agreements largely because of concerns about annual adjustments, particularly for income assistance and education. Assessments were not conducted of recipients with CFAs in our sample and there were no management development plans to guide their progression to more control over their funding. Intervention is focussed primarily on debt reduction and not on sustainable capacity building.

For the other Aboriginal organizations in our sample, there are no multi year funding arrangements despite the long term and supportive nature of their relationship with INAC. There are delays in concluding the single year agreements, delaying payments and potentially affecting the implementation of agreed upon projects and programs. The one exception was the multi year grant to Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey that is provided under a sectoral self-government agreement. MK also has a CFA, however, that provides about 20% of its total funding.

Having provided an overview of funding arrangements and findings about their current status among the different types of recipients, we will now look at each of the key questions in more detail and draw conclusions. We will focus on the funding relationship with First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Aboriginal organizations providing services to First Nations because of the unique history and nature of the relationship between the federal government and First Nations. The study questions have therefore been re-phrased accordingly.

III. Key Questions and Conclusions

A. Appropriateness

To what extent are the funding arrangements used by INAC fit for the program purposes and policy outcomes for which they are customarily used; and to what extent do they leave coverage "holes" in important departmental funding purposes and policy outcomes?

Funding arrangements are the primary instrument through which INAC implements its policies and programs. In that sense they could be considered to support the implementation of all of INAC's Strategic Outcomes, its programs, and its statutory and legislative priorities.

Through funding arrangements, provincial-type services such as education, housing, community infrastructure and social support are being delivered by First Nations, Tribal Councils, Indian administered and provincial/territorial and other organizations to Status Indians on reserves. For most non self-governing First Nations and Tribal Councils, the funding arrangement is the only formally signed ongoing agreement with INAC and by default has become the single most important aspect of the relationship between First Nations and the federal government.

Despite the centrality of funding arrangements to the Department, and the importance of funding arrangements in terms of INAC's relationship with First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Aboriginal organizations, our conclusion is that the leadership, structure and process by which they are managed are not appropriate.

The major criticisms we heard from recipients, INAC officials, other federal departments and experts about the appropriateness of INAC's funding arrangements were:

- It is not clear what the overall objective is in terms of funding arrangements, there is a lack of coherence among programs and funding authorities that make up the arrangements, and there is no clear leadership at Headquarters to coordinate the management and implementation of funding arrangements.

- There is limited engagement of recipients in the funding relationship.

- Funding arrangements do not promote the movement of First Nations, Tribal Councils, and other First Nation administered recipients towards increasingly responsive, flexible, innovative and self-sustained policies, programs or services.

We discuss each of these major comments in further detail below.

Lack of Clarity, Coherence and Leadership

The policy objective related to funding arrangements is not clear. Is it to progressively move FNs towards self government through the assumption of increased responsibilities? Is it to achieve better outcomes by providing greater flexibility to those that are closest to the provision of services, more knowledgeable about the needs of communities or recipients, and more culturally sensitive?

The role of INAC in relation to First Nation governments and First Nations is also not clear. Is it a funding agency providing support to communities and organizations in the achievement of their objectives? Is it a programming agency delivering its programs through agents acting on its behalf?

Responsibility for the design, negotiation, and monitoring of funding arrangements is split between INAC HQ and the regions, and across Finance, Programs and Regional Operations. There is no centre of expertise on grants and contributions, unlike departments such as HRSDC, and no single point of contact for coordination with other federal departments and the Treasury Board Secretariat.

Policy and program officials are often not familiar with the details of funding arrangements and funding authorities, and program terms and conditions can conflict with broader policy objectives or be inconsistent with each other. There is a tendency to increase the number of program authorities and to favour targeted interventions over an increase in the base funding, without sufficient regard for the impact on the recipients that will have to implement the programs.

Recent evaluations have pointed out the need to clarify and better communicate what is required with respect to program objectives, reporting requirements and the respective roles and responsibilities of First Nations, INAC regions and HQ. Too much is added on to funding arrangements in the absence of any other agreements (e.g. governance, redress), and too much is expected from funding arrangements in the absence of any other formal relationship with First Nations. Different Regional Offices, different divisions within HQ, and different individuals take different approaches that can have a major impact on recipients.

Partnerships

There is no real negotiation of funding arrangements with FNs and TCs. They are drawn up and delivered for approval by Chief and Council or the Tribal Council with very little discussion. FNs and TCs perceive it as a "take it or leave it" proposition. Budgeting, allocations and formulae are not well understood and budgets may be cut without warning. For most recipients, there is little discussion of their plans or outcomes; little guidance on best practices; and little opportunity to network and share experiences with others in the same region or across the country.

Funding Service Officers (FSOs), who are the lynchpin in the relationship with FNs and TCs, vary greatly in terms of their dedication, professionalism, knowledge, and attitude. We heard of some excellent FSOs who were considered as partners with their FNs or TCs, who went out of their way to assist and provide advice, and who were being called on for help even after they were no longer formally responsible for the relationship. We also heard of high staff turnover that left FNs or TCs without an FSO for more than a year or with 10 different ones in the past two years; of FSOs who never visited or couldn't be reached, or FSOs who didn't respond to inquiries.

In our three regions, we heard of mechanisms at the regional level to discuss with Chiefs new programs, budgets, allocations, changes from one year to the next in the funding arrangements, and so on. Information from these discussions does not seem to have been relayed back to band managers or Tribal Council administrators in every case, and the suggestion was made that there should be more opportunities for networking and information sharing among this group of professionals and with the regional office.

There is more discussion of funding arrangements with Aboriginal organizations, particularly those that operate on a national scale, but there was not much willingness to adjust the agreement itself, the funding authority, or the amount of funding. Positive approaches identified by the recipients were: engaging in dialogue, acting in partnership, and focussing on long-term plans and budgets.

Promotion of Progress