Archived - Evaluation of the Emergency Management Assistance Program

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: February 24, 2010

PDF Version (228 Kb, 58 Pages)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings – Performance

- 5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Executive Summary

The evaluation of the Emergency Management Assistance Program (EMAP) was required as part of the Transfer Payment Policy and will support renewal of contribution authorities. It provides evidence-based findings and conclusions regarding the relevance and the performance of the program.

The Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) established EMAP to assist First Nations communities living on reserves in managing emergencies. The program covers all four pillars of emergency management: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. In addition, the program may provide assistance for search and recovery activities related to missing persons. In recent years, the range of activities undertaken as part of EMAP has broadened to include health-related issues and civil unrest.

The methodology used to conduct this evaluation included a review of departmental policy and program documents; a literature review on theories of emergency management and how it is structured, delivered, and success measured in other jurisdictions to identify best practices, alternative approaches to design and delivery and possible funding options. The methodology also used interviews with a wide range of key informants from federal, provincial, and local authorities; case studies in four provinces; and focus groups involving representatives from First Nations communities. A Working Group and an Advisory Committee provided guidance and feedback throughout the evaluation process.

Key findings and conclusions from the evaluation are as follows:

Relevance

This evaluation confirms the need for EMAP. There is an overall trend towards increased frequency and intensity of emergencies throughout Canada and First Nations communities are considered "high risk" when it comes to disasters due to their small size, social vulnerability and remoteness and isolation. Many First Nations do not have updated emergency management plans in place leaving them unprepared when emergency events occur.

EMAP is the central tool available to INAC to ensure that required assistance services are provided to First Nations communities facing emergencies. However, the Program, as it is currently designed and delivered, does not meet the needs of First Nations communities in the areas of mitigation, preparedness and recovery.

It should be noted that program authorities and objectives are largely aligned with government-wide priorities as documented in the 2007 Emergency Management Act (EMA), as all are based on the four-pillar approach to emergency management. However, the current program objectives do not appear to capture all departmental priorities. In recent years, INAC has paid increased attention to civil unrest as part of EMAP. While not strictly defined as an emergency in itself, and events frequently occurring off reserve, civil unrest has the potential to erupt into a situation involving emergency services and First Nations communities. Current program authority does not include these types of activities (other than search and recovery activities).

EMAP objectives also do not reference Departmental responsibilities in emergency management in the territories. The actual responsibility of INAC when it comes to emergency management in the North has yet to be clearly established.

One final area of responsibility that is not currently reflected in EMAP's outcomes or authorities is the Department's involvement in emergency activities that are outside INAC's jurisdiction such as pandemic planning. INAC dedicated significant resources to a Health Canada process to have pandemic plans in First Nations communities.

Performance

At the national level, INAC has established the Emergency and Issue Management Directorate to coordinate the program's activities, and support regional offices and other stakeholders as required. INAC's regional offices are collaborating with provincial and territorial emergency management organizations, as well as with Aboriginal organizations. There are formal agreements in place in approximately half of the jurisdictions, and negotiations are ongoing elsewhere.

- Program delivery structure

EMAP's delivery structure for response and some aspects of recovery is sound as the program essentially supports provincial emergency management organizations that can offer the expertise and resources needed in the area of emergency management. However, the current program delivery mechanisms and structure do not provide the required framework to pursue an all hazards approach to emergency management as required by the Emergency Management Act. There is essentially no structure in place to deal with mitigation-related issues. Various approaches are currently used to support preparedness activities, and while flexibility in this area is required, the current program delivery structure does not provide a clear understanding of the scope of EMAP activities related to preparedness.

- Distribution of roles and responsibilities

This evaluation points to a lack of defined roles and responsibilities. In particular, INAC's roles and responsibilities in delivering an all hazards approach to emergency management, especially in the areas of mitigation, preparedness and recovery have not been clearly documented resulting in inconsistencies in programming across Canada.

At the local level, the distribution of roles and responsibilities becomes more complex. Depending on the community involved and the nature of emergencies occurring, there can be a wide range of stakeholders involved. This evaluation indicates that ambiguities do exist in that regard. In particular, some First Nations communities remain uncertain as to the extent of their responsibility in dealing with emergencies, from declaring the emergency itself to carrying out the required activities under the four pillars of emergency management.

The fact that the Department has extended the scope of emergency management activities to include issues such as civil unrest also adds to the complexity associated with the distribution of roles and responsibilities.

Moreover, the precise role of the Department in an all-hazards approach to emergency management in the three northern territories is not well defined, nor are the department's roles and responsibilities with respect to emergency-related activities that fall within the responsibility of another department or jurisdiction (such as health issues).

It is important to note that despite these ambiguities in three of the four pillars of emergency management, response services have not been delayed. This evaluation indicates that when faced with an emergency, local stakeholders will proceed and provide the required assistance. Any unresolved administrative issue is addressed after the fact.

- Current funding structure

EMAP's current funding structure is problematic. It does not provide the required financial base to pursue all of the program's goals and objectives. It also creates inefficiencies in providing the required financial assistance needed to allow INAC to fulfill its legal obligations.

At the time of the evaluation, it was practically impossible to assemble a complete financial picture of EMAP. The requirement to proceed with a new Treasury Board submission every time significant resources are required has triggered unintended negative impacts. In some cases, the Directorate or regional offices need to reallocate funding from other programs to cover some costs. The same situation may occur with band councils. In turn, the incomplete financial picture creates challenges in measuring performance and appropriately documenting the achievements of the program.

Experiences in other settings or jurisdictions confirm that there are a number of options INAC could pursue to improve EMAP's funding structure. Such changes are needed if the program is to successfully pursue program objectives relating to the four pillars of emergency management.

- Program results

The Emergency and Issue Management Directorate is currently collecting only a few indicators related to the number of agreements in place and the number of emergency management plans in place in communities. These indicators measure only a portion of the work being undertaken and do not provide a very useful measure on their own as there are indications that the plans in place are of poor quality, are out dated and have not been tested. Aside from these few indicators, there was no procedure in place to measure and document the program's results, best practices and lessons learned. The Directorate has established founding blocks, such as the development of a departmental emergency management plan, and processes to work and communicate with regional offices. On that basis, the Directorate expects to develop a performance measurement strategy.

At the time of the evaluation, the program's outcomes were concentrated in the area of response and recovery. Despite the lack of agreements in some regions, the Department has succeeded in coordinating and securing the collaboration of emergency management stakeholders to adequately respond to emergencies affecting First Nations communities. However, there were some comments that recovery is focussed primarily on returning evacuees to their communities and restoring damaged infrastructure. It was felt by some that more could be done to help communities deal with the trauma of emergencies and restoring governance following an event.

The program's outcomes in the area of preparedness are more limited. The Department has provided assistance to some First Nations communities in developing plans and providing training. However, evaluation findings indicate that the need for support in this area far exceeds what the program has offered to date. Also, the evaluation has not documented any program results in the area of mitigation, although infrastructure work continues to be among INAC's priorities.

Recommendation 1: Roles and responsibilities

It is recommended that INAC clarify the roles and responsibilities of the Department as they relate to emergency management. This process should consider the current environment of emergency management, specifically the implications of the 2007 Emergency Management Act. To do so, the Department must define relationships with all external stakeholders and put in place the appropriate governance structures and agreements to ensure fulfillment of responsibilities related to emergency management. All aspects of emergency management should be considered in this process, with particular emphasis on the following areas:

- The precise role of the Department in emergency management in the three

northern territories.

- The precise role of the Department with respect to emergencies that

fall within the responsibility of another department or jurisdiction

(such as health issues and civil unrest).

- The program delivery mechanisms and structure relating to the four

pillars of emergency management: mitigation, preparedness, response and

recovery activities.

- Horizontal engagement of other relevant INAC programs that have a potential

to contribute to an all-hazards approach to emergency management, such

as capital infrastructure in mitigation projects or land claims in civil

unrest issues.

- The precise role of First Nations communities in emergency management.

Recommendation 2: Program funding structure

It is recommended that INAC consider a revised funding structure, to alleviate the impact on regions, other program areas, and communities and provide a secure funding base for the Department's emergency activities. To facilitate this transition, INAC should document existing INAC funding for emergency management programming and develop forecasts for future expenses relating to an all hazards approach to emergency management.

INAC should also identify appropriate resources in alignment with the Department's roles and responsibilities. Specifically, ensuring that the department has the ability to provide preparedness and mitigation services in accordance with Departmental obligations under the EMA.

Recommendation 3: Performance measurement

It is recommended that INAC develop a Performance Measurement Strategy for emergency management programming in consultation with the Evaluation Performance Measurement and Review Branch and in accordance with the principles of the new Treasury Board Policy and Directive on Evaluation.

The Final Report for the Evaluation of the Emergency Management Assistance Program was approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on February 24, 2010.

Management Response / Action Plan

| Recommendation 1 | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roles and responsibilities: It is recommended that INAC clarify the roles and responsibilities of the Department as they relate to emergency management. This process should consider the current environment of emergency management, specifically the implications of the 2007 Emergency Management Act. To do so, the Department must define relationships with all external stakeholders and put in place the appropriate governance structures and agreements to ensure fulfillment of responsibilities related to emergency management. All aspects of emergency management should be considered in this process, with particular emphasis on the following areas:

|

INAC recognizes its primary role in fulfilling the federal government's responsibilities to First Nations, Inuit and Northerners as they relate to emergency management. As a first step, the Department has developed the INAC National Emergency Management Plan, approved in May 2009 by the Deputy Minister. The plan provides INAC with a national framework for its roles and responsibilities on emergency management which includes mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery activities in First Nations communities across Canada. | ||

In addition to the INAC National Emergency Management Plan and to address recommendation 1 as described, INAC will be working with the Senior Officials Responsible for Emergency Management (SOREM) First Nations, Inuit and Northerners Working Group to establish a national approach to emergency management Service Agreements with the provinces/territories. As part of this, the SOREM Working Group made up of intergovernmental representatives will support the development of a clear national INAC framework on emergency management, including mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery for:

|

Director, Emergency and Issues Management Directorate | Implementation work has already been initiated with a planned completion date of October 2011 tied to EMAP authority renewal. | |

| INAC's EIMD and Northern Affairs Organization (NAO) are currently collaborating on developing an annex to INAC's National EM Plan to clarify INAC's emergency roles and responsibilities in the North. INAC's precise role with respect to emergencies that fall within the responsibility of another department or jurisdiction (such as health issues and civil unrest) is known and must simply be better communicated to stakeholders. For example, INAC worked closely with Health Canada's First Nation and Inuit Health Branch to develop a joint action plan, based on the Department's role as set out in Annex B of The Canadian Influenza Pandemic Plan for the Health Sector. The joint action plan clearly described INAC's precise role during the H1N1 emergency. INAC also participates in Public Safety's Interdepartmental Working Group on the All Hazards Risk Assessment Framework for increased collaboration at the federal level. Although better communication and coordination has been achieved since the creation of the Emergency and Issue Management Directorate in September 2008, work is ongoing to develop stronger links to other relevant INAC programs to reinforce the all-hazards approach to emergency management in the Department. |

Director, Emergency and Issues Management Directorate, in collaboration with the Director of Devolution and Major Programs at NAO | June 2010 |

| Recommendation 2 | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program funding structure: It is recommended that INAC consider a revised funding structure, to alleviate the impact on regions, other program areas, and communities and provide a secure funding base for the Department's emergency response and recovery activities. To facilitate this transition, INAC should document existing INAC funding for emergency management programming and develop forecasts for future expenses relating to an all hazards approach to emergency management. INAC should also identify appropriate resources in alignment with the Department's roles and responsibilities as determined in the response to Recommendation 1 above. Specifically, ensuring that the department has the ability to provide preparedness and mitigation services in accordance with Departmental obligations under the EMA. |

INAC will use the present evaluation and authority renewal process to further investigate and determine the most appropriate funding structure to meet all of the Department's legal and contractual obligations regarding emergency management in its area of responsibility while alleviating unintended impacts on regions, other program areas and affected communities. To support this exercise, the Department has started to track and document all emergency management related expenses for better forecasting purposes. Also as part of this, INAC will develop options to secure appropriate resources in alignment with the Department's roles and responsibilities for emergency management assistance as well as obligations under the EMA. |

Director General, Regional Operations Sector | As part of the EMAP authority renewal scheduled for completion by October 2011, a funding structure to reflect the Department's legal and contractual obligations will be developed for approval. |

| Recommendation 3 | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance measurement: It is recommended that INAC develop a Performance Measurement Strategy for emergency management programming in consultation with the Evaluation Performance Measurement and Review Branch and in accordance with the principles of the new Treasury Board Policy and Directive on Evaluation. |

The Department is in agreement with this recommendation. The Performance Measurement Strategy and the EMAP authority renewal process will be completed simultaneously. | Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations Sector | The Performance Measurement Strategy will be developed once the EMAP authority has been extended by March 31st, 2010 and will be completed by October 2011. |

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This document constitutes the final report of the evaluation of the Emergency Management Assistance Program (EMAP). The primary purpose of this program is to allow the federal government to assist First Nations communities living on reserve and, under some circumstances, Canadians living north of the 60th parallel, to cope with emergencies that significantly affect their communities. The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (part of the Audit and Evaluation Sector) initiated this evaluation in June 2009. The Branch contracted the services of PRA Inc. to provide assistance during all stages of the evaluation process.

This evaluation is required as part of the Transfer Payment Policy and is expected to support the renewal of contribution authorities associated with EMAP, which are due to expire at the end of March 2010. The evaluation is expected to provide evidence-based conclusions regarding relevance and performance (efficiency, effectiveness, and alternatives), particularly with respect to the financing, design, and delivery of EMAP.

This report is divided into five sections. This introduction provides an overview of the evaluation process, along with a description of EMAP. Section 2 describes the methodology associated with the study. It includes a description of the scope and timing of the evaluation, a summary of the evaluation issues and questions addressed in this report, along with a description of the various methods used to collect evaluation data and findings. Section 2 also provides an overview of the roles, responsibilities, and quality assurance used to support this study. Section 3 and 4 include the most critical information relating to the evaluation of EMAP, as they summarize all findings that have emerged during the data collection process. Section 3 specifically explores the relevance of EMAP, while Section 4 focuses on the actual performance of the program. Finally, Section 5 provides conclusions and recommendations as applicable.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

An emergency is a circumstantial notion. It typically refers to situations where a community is overwhelmed by unforeseen or extraordinary events that it can no longer manage using its normally available resources and capacity. Public Safety Canada offers this definition of emergencies:

"[A] social phenomenon that results when a hazard intersects with a vulnerable community in a way that exceeds or overwhelms the community's ability to cope and may cause serious harm to the safety, health, welfare, property or environment of people; may be triggered by a naturally occurring phenomenon which has its origins within the geophysical or biological environment or by human action or error, whether malicious or unintentional, including technological failures, accidents and terrorist acts."[Note 1]

The degree to which a community is impacted by an emergency event will depend on the local context. What may be an inconvenience in a large urban centre may well turn out to be an emergency in a small and remote community. It is well established that the size of a community, and its relative isolation, can have a direct impact on its resiliency when faced with an emergency.[Note 2] Since First Nations communities are often small and remote, they are particularly vulnerable when faced with unforeseen events. This is particularly significant in the current global context, where the frequency and severity of emergencies are increasing.[Note 3]

The nature and range of emergencies that may affect a community contribute to the complexity of emergency management. As it relates specifically to First Nations communities living on reserve, the list of emergencies with which they may be confronted includes both naturally occurring and human-induced emergencies:

- Natural emergencies include (but are not limited to) wildfires, floods,

major ice jams, avalanches, tornadoes, landslides, periods of intense

cold weather, power blackouts, and severe storms;

- Human-induced emergencies include (but are not limited to) bomb scares, fuel tank accidents, oil spills, gas leaks, train derailments, consequence management supporting pandemic and communicable disease outbreaks (e.g., H1N1), civil unrest, and lost persons cases.

Another factor that contributes to the complexity of emergency management is the range of emergency management partners that need to be involved in the successful management of actual or potential emergencies. The list of these organizations includes planners, responders, recovery and financial personnel. Firefighters, police services, health care providers, social services providers, band councils, mutual aid partners, emergency management organizations, and provincial and federal governments are among the stakeholders that need to efficiently coordinate their actions and decisions so that an emergency can be successfully managed. In any circumstance, this would be a remarkable challenge: in a period of crisis, this is even more testing.

Over the past 20 years, the specific role of INAC in managing emergencies on reserve and north of the 60th parallel has become increasingly structured. The Department has a long-standing involvement, dating back to the 1960s, in dealing, to some extent, with emergencies relating to these communities. The passing of the Emergency Preparedness Act in 1988 provided somewhat clearer parameters for defining INAC's role. The act requires every Minister be accountable to Parliament to identify "civil emergency contingencies that are within or related to the Minister's area of accountability" and to develop a civil emergency plan.

During this period, EMAP has emerged in an incremental fashion. The federal government established the program's first building block in 1988, when it provided INAC with the authority and resources to support fire suppression services when forest fires (or similar incidents) affected First Nations communities living on reserve. It also allowed the Department to provide financial assistance to First Nations for search and recovery activities related to lost persons, based on compassionate grounds after local authority has called off search and rescue for the continuation of search activities.

The federal government established the program's second building block in 2004, when it expanded the 1988 departmental authority to include activities and services relating more broadly to emergency management. Not only is the Department in a position to support fire suppression services, as well as search and recovery activities, but it also gained the authority to support a range of activities related to mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery. While the Department gained that authority, it did not secure incremental funding on a permanent basis (A-base), to support this expanded mandate. Rather, the federal government has been providing funding on an ad hoc basis (supplementary estimates). This funding aspect is further discussed in subsection 1.2.4. The federal government approved the Terms and Conditions that set the parameters for the current EMAP mandate for a five-year period, from 2005–2006 to 2009–2010.

The passing of the federal Emergency Management Act in 2007 has provided further clarifications on the roles and responsibilities of all federal ministers. First, the new act provides a definition of emergency management, which includes the "prevention and mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from emergencies." These are the well-established four pillars of emergency management, which are further explored in subsection 3.1 of this report. The act requires each minister accountable to Parliament to identify the risks "that are within or related to his or her area of responsibility" and, on that basis, to prepare, maintain, and test emergency plans. Among other things, these plans must include:

- any programs, arrangements, or other measures to assist provincial

governments and, through the provincial governments, local authorities;

- any federal-provincial regional plans;

- any programs, arrangements, or other measures to provide for the continuity of the operations of the government institution in the event of an emergency.[Note 4]

It is important to note that the current authority associated with EMAP covers activities occurring on First Nations reserves. EMAP's current Terms and Conditions do not technically cover activities north of the 60th parallel, other than those occurring in the two reserves located in the Northwest Territories.

1.2.2 Program Logic

This subsection describes EMAP's program theory. Simply put, the purpose of this subsection is to better understand what the program is expected to do and what it is expected to achieve. Whether these activities have occurred or these results have been achieved is discussed in Section 3 (evaluation findings). Here, the goal is to understand the program as it was initially designed, and lay out the set of assumptions that link its activities with its expected outcomes. A visual summary of the program's logic model is included in this report as Figure 1, on page 7.

This Logic Model was created as part of this evaluation and was shared with EMAP staff participating in key informant interviews for comment. It is important to emphasize at this juncture that the program theory outlined below varies from the actual activities, outputs and outcomes of the EMAP. Section 4.1 outlines the significant gaps in EMAP's coverage of the four pillars.

Program Objectives

The fundamental purpose of EMAP is to protect First Nations communities living on reserve when they face unforeseen emergency events that they can no longer handle using their normally available resources. This includes the protection of both individuals themselves and their overall community infrastructure. More specifically, the program pursues three objectives:

- To protect the health and safety of First Nations members when

they face natural disasters and damages or destruction of community

infrastructure and houses, by natural disaster or accident;

- To assist in the remediation of essential infrastructure and

houses through timely assessment of emergency needs and the facilitation

of an appropriate emergency response from other areas of INAC;

- To support communities, on a compassionate basis, through the continuation of search and recovery activities associated with lost persons beyond the expected survival period after search and rescue authority has called off search.

Program Activities and Outputs

To pursue these objectives, the Department has authority to undertake a number of activities and provide financial assistance as required. These program activities can be grouped along the four pillars of emergency management.

Mitigation: These activities may provide assistance to First Nations communities to identify systemic vulnerabilities. This assessment process may be undertaken by the community itself, or may be done in collaboration with an external emergency management organization. INAC regional offices may also work with First Nations communities to identify capital projects that could be included in the departmental long-term capital plan. It is important to note that EMAP does not directly fund capital projects. What comes out of mitigation activities may include risk or impact assessments, training, or the inclusion of specific mitigation-related projects in the departmental capital plan.

Preparedness: Under this heading, the program may provide assistance to First Nations communities to undertake a number of activities related to emergency management planning. INAC regional offices may negotiate various types of agreements with emergency management or other organizations to assist First Nations communities in developing, updating, and testing emergency plans. As a result, these activities may lead to the signing of agreements, training tools and resources, and emergency plans.

Response: In the event that an emergency unfolds, EMAP may provide assistance to First Nations communities to protect individuals and community infrastructure. INAC regional offices typically work with emergency management organizations to ensure that any required evacuations, response activities (such as providing alternative sources of energy), or other measures are taken to address the emergency at hand. In some cases, INAC regional offices may provide direct financial assistance to First Nations communities to respond to a specific emergency. To support these activities, INAC may sign agreements with response organizations or assist in the coordination of activities.

Recovery: Depending on the nature of emergencies, recovery activities may include the repatriation of evacuated families and individuals, repairs to damaged infrastructure, and other related measures needed to bring the community back to pre-emergency conditions. Again, these activities may be undertaken by an emergency management organization or by the community itself via capital projects. As a result, agreements may be signed with an emergency management organization and financial payments may be made directly to band councils.

Expected Outcomes

These various activities are expected to enhance the resiliency of First Nations communities and to provide comparable emergency management services to First Nations communities as found in non-Aboriginal communities in similar circumstances. More specifically, activities undertaken through EMAP are expected to contribute to the following immediate and intermediate outcomes:

- First Nations communities undertake mitigation projects that

are required to address their systemic vulnerabilities.

- First Nations communities enhance their capacity to effectively

plan for emergencies and to collaborate with other partners.

- Efficient and effective responses to emergencies affecting First Nations communities are implemented and relative normalcy is restored following the emergency. This, in turn, is expected to minimize the social and economic impacts of emergencies on First Nations communities.

Ultimately, the program is expected to contribute to the broader departmental goal of having First Nations benefit from their lands, resources, and environment on a >sustainable basis.

Logic Model Emergency Management Assistance Program (EMAP)

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the logic model for the Emergency Management Assistance Program. A logic model is a chain of results connecting activities to their final outcomes and identifying the steps in between that demonstrate the progress towards each goal. In this logic model, the progression from activities to outputs and then outcomes is displayed vertically with a box from each row linked to the one above it using arrows, demonstrating how the program activities indicated in the logic model lead to specific outputs which in turn lead to immediate outcomes, intermediate outcomes, and the final outcome.

In total there are four columns, one for each pillar of program activity, and six rows, with the first row listing the four main pillars of program activities. The second row details the specific activities undertaken for each pillar, the third row lists outputs, and the fourth, fifth and sixth rows state the immediate, intermediate and final outcomes respectively.

At the top of the chart, in the first row, the four main pillars of program activity are each represented by their own box. In order from left to right we have: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. Each of these boxes is connected to a box below, in the second row, which is then connected to the one below it and so on, continuing down to the last row, forming four columns.

In the first column under mitigation, the box in the second row lists the following activities: identify possible emergencies; identify vulnerable peoples and infrastructure; identify capital projects for inclusion in INACs long term capital plan. This then links to the box in the third row below indicating the outputs for these activities: risk and impact assessments; workshops on risk mitigation; mitigation projects in capital plan. In the next row, the box for immediate outcomes associated with mitigation states: mitigation projects under way in communities, followed by the box for intermediate outcomes in the fifth row which states: community vulnerabilities addressed.

In the second column under preparedness, the activities listed in the second row are: identify eligible costs for reimbursement; negotiate agreements with provincial/territorial BMOs; promote community engagement in emergency management; training community level and INAC Emergency Management officials; develop and implement emergency pans and procedures. The outputs which follow in the third row state: agreements with BMOs; information sessions; training tools, materials, sessions; emergency plans (national, regional, and community), policies, and procedures; continuous monitoring systems. The corresponding immediate outcome in the fourth row is: capacity building in Aboriginal communities, and the intermediate outcome in the fifth row is: partners prepared for possible emergency events.

In the third column under response, the stated activities are: engage partner organizations; coordinate response activities; establish chain of command; evacuation; monitor and report on emergency situations; identify source of INAC funds for services rendered. The box detailing outputs in the third row states: emergency coordinating mechanisms; finance emergency response effort, and the immediate outcome below states: efficient and effective response to emergency events. The intermediate outcome listed in the fifth row reads: social and economic impact of emergency events minimized.

The fourth and last column, found on the far right of the page, corresponds to the activity pillar for recovery. In the second row, the box corresponding to this pillar lists the following activities: repatriation of evacuated individuals; identify capital projects for inclusion in INACs long term capital plan; review best practices; prepare TB submissions to recover funds. In the next row, the outputs identified are: communities repatriated; recovery projects in INAC capital plan; incident review (after action report); TB submissions. The immediate outcome, indicated in the fourth row states: return to normalcy following an emergency event. At this point, when we get to the fifth row listing the intermediate outcomes, the columns for response and recovery both connect to the same box. Although both columns have their own separate boxes for each activity, output, and immediate outcome, they now share the intermediate outcome of: social and economic impact of emergency events minimized.

Finally the sixth and last row contains one box which is connected to each of the four columns. At this point all of the four columns share the final outcome for the program which is: First Nations and Inuit benefit from their lands, resources, and environment on a sustainable basis.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders, and Beneficiaries

INAC's Emergency and Issue Management Directorate is responsible for the overall management of EMAP. The Directorate provides both policy and operational support for the ongoing implementation and management of the program.

INAC's regional offices also play a predominant role in the ongoing management of EMAP. These regional offices work directly with emergency management organizations, Aboriginal organizations, and band councils. At the time of this evaluation, all provincial regional offices had at least one position dedicated to emergency management. Individuals in these positions liaise with all key stakeholders involved in emergency management, particularly in the areas of preparedness (emergency management planning), response, and recovery. In the three territories, responsibilities for emergency management are added to existing positions.

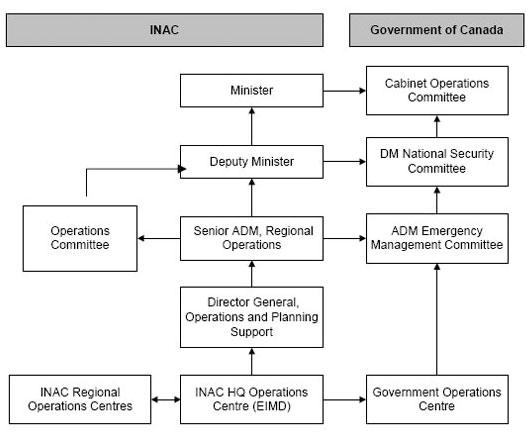

INAC's Emergency Management Goverance Structure

Figure 2

Figure 2 depicts a chart showing the governance and decision making infrastructure within INAC and the Government of Canada as a whole in relation to emergency management. At the top are two boxes with the one on the left indicating INAC and the right showing the Government of Canada.

Under Government of Canada, at the bottom right corner, is a box for the Government Operations Centre. This box then has an arrow which points up to another box called ADM Emergency Management Committee which in turn has an arrow up to DM National Security Committee which then has an arrow pointing up to a box titled Cabinet Operations Committee.

Under INAC, at the bottom and to the far left there is a box for Regional Operations Centres. A double ended/reverse arrow then points to a box to the right for HQ Operations Centre. This box then has an arrow pointing up to Director General, Operations and Planning Support which then has an arrow pointing up to Senior ADM, Regional Operations. That box points to another on the left called Operations Committee as well as to the one above it titled Deputy Minister. The Deputy Minister box then has an arrow pointing up to the top box titled Minister.

There are also arrow links between some of the INAC and Government of Canada boxes. Specifically, HQ Operations Centre has an arrow leading to Government Operations Centre; Senior ADM, Regional Operations links to ADM Emergency Management Committee; the Deputy Minister connects with the DM National Security Committee; and, the Minister box has an arrow connecting it with Cabinet Operations Committee.

The work of INAC in emergency management is part of a much broader web of decision-making infrastructure within the Department itself, and the government of Canada as a whole. As illustrated in Figure 2, the Department has established an informal Operations Centre in its headquarters for normal operations that can be escalated to a fully functional emergency operations centre for large emergencies, all of which is directly supported by the Directorate. The Department also has an Operations Committee, where several senior managers coordinate their respective activities in emergency management. Within the government itself, there are a number of decision-making bodies that range from an Operations Centre, up to the Cabinet Operations Committee.

The ultimate beneficiaries of EMAP are First Nations communities and specific individuals and families within these communities that are affected by emergencies. From an administrative point of view, however, the program does not provide direct funding to individuals and families. Instead, the funding is provided directly to those organizations that are providing emergency management services. The list of these organizations may include:

- Emergency management organizations

- Aboriginal firefighters association (in BC and MB)

- Provincial governments

- Band councils

1.2.4 Program Resources

EMAP's funding structure is both unusual and complex. The set of activities undertaken by the program is funded through a variety of sources, some of which are specifically dedicated to EMAP, while others result from internal reallocations. This subsection describes these various sources of funding currently used to support EMAP activities.

The Formal A-base Funding

The federal government provides ongoing funding to EMAP (A-base funding) in the amount of $10.7 million per year (as of fiscal year 2008–2009). This amount includes $9.5 million in transfer payment resources (contributions), which are specifically assigned to fire suppression activities. As indicated in subsection 1.2.1 of this report, these resources were associated with the authority given to INAC in 1988 to support fire suppression activities affecting First Nations communities living on reserve. An additional $1.2 million is assigned to operating expenditures to cover some of the departmental internal costs associated with emergency management.

For any other financial resources needed to support EMAP activities (particularly in the areas of preparedness, response, and recovery), the Department is left with essentially two options. It may decide to reallocate some existing resources assigned to other programs (capital projects, for instance) to fund EMAP activities. It may also decide that reallocating resources is no longer feasible or appropriate and, on that basis, it may seek supplementary funding.

Supplementary Funding

Over the past five years, since costs associated with emergencies affecting First Nations communities have far exceeded the initial $9.5 million available for fire suppression, the Department has had to turn to the Treasury Board to obtain supplementary funding. As indicated in Table 1, the federal government has allocated $113.7 million over a five-year period in additional funding to EMAP. These funding requests are typically event-based, as they cover costs associated with specific emergencies.

In addition to these amounts, the federal government has allocated resources to address emergency related expenditures using the Capital Facilities and Maintenance programs. These expenditures were typically allocated to repair damaged infrastructures or to address rising fuel costs.

| Fiscal year | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| 2004-2005 | 0 |

| 2005-2006 | 13,090,000 |

| 2006-2007 | 48,296,000 |

| 2007-2008 | 25,980,000 |

| 2008-2009 | 26,376,971 |

| Total | 113,742,971 |

| Source: Administrative data. Note: These numbers only include allocations made through EMAP. It excludes emergency related expenditures made through the Capital Facilities and Maintenance program. |

|

In each case, the Directorate must prepare a Treasury Board submission on behalf of INAC's Minister. Because of the requirements associated with Treasury Board submissions, obtaining these additional resources may require a fair amount of time. Meanwhile, not knowing what the Treasury Board decision will be, the Department (regional offices, in particular, or band councils themselves), have to cash manage the expenditures that have already been committed.

Other Funding Contributing to Emergency Management

There are at least two additional sources of funding that support EMAP-related activities. The first of these is A-base funding allocated to the Department's headquarters or regional offices, which is redirected to support emergency management activities. As previously mentioned in this subsection, the Directorate or regional offices may decide that pursuing supplementary funding through Treasury Board submissions is not the most appropriate strategy for covering the costs related to a specific incident. These decisions, in turn, will affect other programs and activities.

The second source of funding is a program administered by Public Safety Canada called the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (DFAA) program. This provides funding to provinces and territories for emergencies on reserve on the rare occasion when an emergency affects a large territory that includes one or more First Nations reserves. Once certain criteria are met (based on the total amount of eligible expenditures incurred to address an emergency), the DFAA program reimburses any response and recovery expenses related to activities on First Nations reserves that meet the program's guidelines. In the absence of the DFAA program, it can be expected that EMAP would need to cover these costs.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

This evaluation focuses on EMAP activities that occurred during a five-year period, from 2004–2005 to 2008–2009. The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee approved the Terms of Reference for this evaluation in June 2009. The evaluation team conducted the field work between August 2009 and January 2010.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In accordance with Treasury Board policy on evaluation, the EMAP evaluation addresses a number of evaluation questions relating to the relevance and performance of the program. Table 2 includes all of the evaluation issues and questions addressed in this report.

| Relevance |

|---|

| 1. Is there an anticipated future demand for EMAP as it is currently designed and delivered? |

| 2. Do the objectives of EMAP continue to be consistent with departmental and government-wide priorities? Specifically, the 2007 Emergency Management Act? |

| 3. Does EMAP duplicate or overlap programs or services provided by INAC or other stakeholders? Are there any gaps in delivery compared with other government departments, jurisdictions, or governments? |

| Performance (Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Economy) |

| 4. Are the current program delivery mechanisms and structure appropriate and effective for achieving EMAP and government objectives, including the Emergency Management Act? |

| 5. To what extent have recommendations from the 2007 internal evaluation been implemented successfully? To what extent are remaining recommendations still relevant? |

| 6. Are the roles and responsibilities of different EMAP divisions and stakeholders well-defined? Are they appropriately divided? |

| 7. How appropriate and effective are EMAP's current means of obtaining funding and its distribution of funding? |

| 8. How effectively are EMAP results, outcomes, and best practices/lessons learned measured and documented? |

| 9. Is EMAP producing expected outputs and achieving expected outcomes? Are there identifiable factors that inhibit or abet EMAP success? Are results consistent with best practices or accepted benchmarks for success in emergency management? |

| 10. Have any unintended impacts been observed, positive or negative, as a result of activities conducted under EMAP? |

2.3 Evaluation Methods

The EMAP evaluation rests on evidence-based findings that were collected using a number of research methods. This subsection describes these various methods, along with a discussion on the rationale for these methodological choices, and the challenges that were faced during the study.

2.3.1 Data Sources

Five data sources were used in support of the EMAP evaluation:

Document and Data Review

The document and data review involved a thorough review of program files, background documents, agreements, performance measurement materials, and further documentation regarding the role of INAC and related stakeholders in dealing with emergency management. This review covered issues relating to First Nations communities living on reserve and to federal land north of the 60th parallel. The document and data review formed a significant source of information for this evaluation, as it addressed all evaluation issues and questions.

Literature Review

The literature review focussed on two broad areas. Firstly, it examined current theories of emergency management to inform the relevance and need of EMAP. These findings provide some of the context for assessing the program rationale.

Secondly, the literature review examined how emergency management programs are structured and delivered in other jurisdictions, including:

- Models of emergency management from other countries, especially approaches

tailored to Aboriginal populations. Australia, the USA, and New

Zealand were identified as possible countries for study.

- Emergency management in other Canadian government departments and other

jurisdictions (i.e., provinces and municipalities).

- Other emergency management organizations, with a focus on how emergency management is planned and structured in other countries, other departments, and other jurisdictions; objectives and outcomes; how success is measured; and how emergency management is funded.

The second area of the literature review helped to identify best practices relating to program design and delivery and funding structures. Alternative approaches related to management and performance measurement in other departments, jurisdictions, and organizations allowed for a comparative analysis with EMAP and informed program design and delivery, performance measurement, and funding options.

This review relied on primary (government policies, legislation, and acts) and secondary (program descriptive reports, and academic journals and publications) sources of data.

Key Informant Interviews

In-depth key informant interviews were used to investigate each evaluation issue and question. At least six distinct stakeholder groups were identified to be interviewed in order to capture a diverse range of perspectives on evaluation questions and issues.

A total of 32 interviews were conducted with individuals from the following groups:

- INAC senior management (in regions and headquarters) (n=2)

- EMAP officials (headquarters and regions) (n=11)

- Provincial and territorial governments' emergency management

organizations (n=7)

- Representatives of other emergency management organizations outside

INAC (n=3)

- Aboriginal organizations (n=6)

- Experts in the field of emergency management (n=3)

Before scheduling interviews, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch emailed key informants an introductory letter that described the objectives of the evaluation and explained that PRA Inc. would contact them to schedule an interview. In most cases, interviews were conducted by telephone. Interviews were conducted in key informants' preferred official language. Prior to conducting the interview, key informants were provided with an interview guide so that they could offer thoroughly considered responses. Separate interview guides were prepared for each category of key informant. Key informants were assured anonymity in the Final Report.

Case Studies

A total of four case studies were performed in order to review existing EMAP operations within Aboriginal communities. In three cases, site visits were conducted to allow for the close examination of evaluation issues. The focus of these visits was to examine EMAP's role and experience at each site.

In close collaboration with INAC's regional offices, potential communities were identified and a letter from INAC was sent formally inviting them to participate in the process. The selection of sites was based on the following criteria:

- Size of the community (including at least one small, medium, and large

community)

- Must have responded to an emergency event during the 2004/05 to 2008/09

period

- Variance in the type of emergency event responded to (i.e., flood, fire, health risk, civil issue, etc.)

A case study template was designed to systematically record information for each site. Interviews with relevant stakeholders such as provincial representatives, regional emergency management officials, and community representatives were performed at each site. A short case study report (approximately five to seven pages) was drafted for each of the site visits.

Focus Groups

A total of five focus groups were employed to gather views and insights from community representatives located in various regions of the country. These focus groups investigated evaluation issues related to program relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, and alternatives. A total of 16 individuals from First Nations communities participated in these focus groups.

2.3.2 Considerations, Strengths, and Limitations

The methodology used for the evaluation of EMAP was structured to allow for a thorough review of documented or undocumented facts about the program, and for the gathering of opinions and perceptions of all key stakeholders involved in EMAP, including First Nations communities and organizations, provincial and territorial organizations, and INAC representatives.

Since the evaluation relied heavily on qualitative data, qualitative data analysis software (NVivo) was used to systematically structure the findings and allow for a complete integration of all qualitative lines of evidence. In particular, this approach supported an analysis by regions, which was particularly important considering regional variations in emergency management across INAC and Canada.

One challenge encountered during this evaluation related to the ongoing evolution of the program. Over the time period covered by this evaluation, INAC implemented a number of changes to EMAP, particularly as it relates to its management structure. This report attempts to adequately reflect these changes.

Another challenge faced related to the site visits and focus groups. Finding community representatives to participate in these two activities has proven challenging in some regions. This resulted in some delay in the data collection process, and some modification to the methodological approach.

It should be emphasized that these methodological challenges did not substantially affect the data collection process, nor the validity of the findings presented in this report.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities, and Quality Control

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch and PRA Inc. worked collaboratively during the design, data collection, and analytical phases of this evaluation study. To this end, they benefited from the support of two committees:

- Working Group: A Working Group was established and made up

of INAC employees from headquarters and four regional offices. Its mandate

was to provide advice and guidance on the management and delivery of

the EMAP program, identify key informants to interview, and validate

findings.

- Advisory Committee: An Advisory Committee was also established and made up of individuals who have extensive experience in emergency management and have an interest in the EMAP program. The mandate of the Advisory Committee was to provide strategic advice to the evaluation during the early stages (to provide advice and guidance on the evaluation questions and proposed methodology) and the late stages (to review evaluation findings, conclusions, and recommendations).

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

This section explores the relevance of EMAP. In doing so, it provides an assessment of the anticipated future demand for EMAP from a First Nations perspective, reviews departmental responsibilities and the impact on EMAP of other issues falling within the department's mandate. EMAP's contribution to government-wide priorities is examined through an assessment of the requirements of the 2007 Emergency Management Act and the expected activities associated with the theory of the four pillar approach. This section also looks at issues of duplication and overlap and potential gaps in delivery through an examination of other relevant programs dealing with emergency management.

3.1 The Role of INAC in Emergency Management

3.1.1 The Legal Responsibility of INAC

At a fundamental level, the relevance of EMAP is directly linked to the well-established responsibility of INAC to First Nations communities living on reserve. Section 91.27 of the Constitution Act prescribes the legislative authority of the federal government for "Indians and Lands reserved for Indians." To this end, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act states that the "powers, duties and functions of the Minister extend to and include all matters over which Parliament has jurisdiction, not by law assigned to any other department, board or agency of the Government of Canada, relating to Indian affairs." It is on that basis that the Department has historically provided assistance to First Nations facing emergencies, well before the establishment of EMAP.

The Emergency Management Act (2007)

The passing of the Emergency Management Act in 2007 provided further clarifications as to the extent of the Department's responsibility in emergency management. Under the Act, the Minister is responsible for mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery for emergencies on reserve. The INAC Minister must identify "risks that are within or related to his or her area of responsibility" and prepare "emergency management plans in respect of those risks." It is further expected that such plans would be maintained, tested, and implemented, and that exercises and training would be conducted accordingly.

EMAP provides an important means by which the Department may fulfil its legal obligation to First Nations communities living on reserve, so in response to this new legislation, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Socio-economic Policy and Regional Operations initiated an evaluation of EMAP. The evaluation was to inform new policy development and examine the fiscal pressures of emergency management on the Department. The evaluation was completed in July 2007 and resulted in 39 recommendations.

The majority of the recommendations were very specific and operational in nature such as the creation of a new directorate for emergency and issue management with permanent FTEs and A-base funding for HQ and a number of regions. There were three specific recommendations with respect to First Nations Emergency Services Society (FNESS) in British Columbia. The recommendations also touched on the need to define roles and responsibilities of new positions, mandatory training for staff, and business continuation planning in FN emergency management plans.

As a result of the 2007 evaluation, INAC established the Emergency and Issue Management Directorate and made progress on many of the recommendations. At the time of the current evaluation, the Directorate completed a National Emergency Management Plan and is actively developing a process and guidelines for the negotiation of emergency management agreements and the identification of eligible expenses for reimbursement which were also recommended in the 2007 evaluation. There are approximately ten recommendations from the 2007 evaluation where the new Directorate has not made significant headway:

- INAC formally endorse and promote, through policy development, an all

hazards approach to emergency management which includes mitigation, preparedness,

response and recovery (recommendations 2 and 3).

- Mitigation as a philosophy be developed in all sectors including capital

expenditures and land claim negotiations (recommendation 2).

- Funding be made available for the development, updating and testing

of emergency management plans (recommendation 20).

- Funding be made available for emergency management positions at the

community or Tribal Council level where there was a demonstrated need,

and for training or information sessions for newly elected Chiefs and

Band Councils (recommendations 21 and 22).

- Establish clear concise measureable goals for monitoring progress on

emergency management plans (recommendation 20).

- INAC move forward with a Memorandum to Cabinet to update financial authorities

and obtain sustainable funding to provide an effective emergency management

program to First Nations (recommendation 31).

- Authority be sought from Treasury Board to create an emergency management

reserve that can be easily accessed for extraordinary emergencies (recommendation

32).

- The department initiate a legal review to determine the best manner

to legislatively provide authority for a First Nations community to declare

an emergency to protect the federal and provincial governments from potential

civil litigation (recommendation 35).

- The department enter into a partnership with Health Canada in the development

of emergency planning so that pandemic issues are included in the all

hazards approach to emergency management (recommendation 36).

- The Department formalize a best practices policy designed to ensure all regions benefit from existing best practices. (recommendation 39).

Responsibilities relating to the territories

While the foundation allowing the Department to intervene in an all hazards approach to emergency management does exist, there are other departmental priorities that are not adequately captured in EMAP such as the situation in the three territories. According to the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, the Minister's duties extend to all matters relating to "Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut and their resources and affairs; and Inuit affairs." As it currently stands, EMAP allows the Department to intervene in the two First Nations reserves located in the Northwest Territories. Beyond that, there is far less certainty. In cases of emergencies affecting self-governing First Nations and land set aside for First Nations located in the Yukon, this evaluation has found no consensus on what the role of the Department should be. In any case, the current program authority associated with EMAP does not cover activities off-reserve.

At the time of the evaluation, the Department was developing a policy statement on the North, which acknowledges the federal government's responsibility to manage Crown land, as well as water and resources, on federal land located in the three territories. These functions include the management of emergencies affecting such land. The statement also recognizes the government's responsibility for contaminated sites in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. Based on these principles, the question remains as to which department should lead emergency management in these areas. Evaluation findings on this question are inconclusive. Should the answer point to INAC, it should be emphasized again that the current structure of EMAP does not provide the foundation to intervene in these circumstances. The Department would need to either establish another emergency management program, or extend the current EMAP authority to formally include activities in the territories (beyond the two reserves in the Northwest Territories).

Managing other issues

In addition to the North, ambiguities also persist as to the role of INAC in activities falling beyond the strict parameters of the Department's legislative responsibility. The three primary cases that emerged from this evaluation are civil unrest, health-related issues (such as H1N1), as well as search and recovery activities.

There is little doubt that civil unrest incidents involving or relating to Aboriginal communities is of prime interest to INAC. For instance, the Ontario region has, in recent years, witnessed an increasing number of events regarded as civil unrest involving First Nations. The most notable of these is the escalation of the Grand River land settlement protests into highway blockades, prolonged land occupations, and several incidences of violent interactions between First Nations protesters, non-First Nations residents of surrounding areas, and Ontario Provincial Police officers. The prime responsibility for dealing with civil unrest events occurring off-reserve does not rest with INAC. However, the outcome of these events has a direct impact on First Nations and, by extension, on the Department. This explains why the INAC regional office in Ontario now has staff dedicated to monitoring civil unrest events involving First Nations. This, again, falls beyond the current EMAP program authority.

The same logic largely applies to health issues affecting First Nations communities. The recent pandemic events, linked to H1N1, required extensive coordination and monitoring efforts on the part of INAC and Health Canada. Ultimately, it is Health Canada (its First Nations, Inuit and Aboriginal Health Branch) that has legal responsibility for dealing with health-related issues affecting Aboriginal Canadians.[Note 5] Regardless, INAC staff has had to allocate considerable resources to support the work of Health Canada in dealing with this emergency. How such activities relate to EMAP remains unclear.

Whereas emergency management tends to focus on collective needs, search and recovery activities typically focus on one individual, or a few. Strictly based on compassionate grounds, and not as a result of a clearly established legal responsibility, the Department may provide assistance to pursue search and recovery efforts for missing individuals when the first response effort has been unsuccessful. This assistance is typically provided until no hope of recovery remains.

3.1.2 The Four Pillars of Emergency Management

The Emergency Management Act formally incorporates the four-pillar approach to emergency management. The Act specifically defines emergency management as including "the prevention and mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from emergencies." This approach is widely supported in the literature on emergency management. While traditional emergency management had a focus on response and recovery, mitigation and preparedness are now playing a prominent role in that field. Combining prevention and mitigation into one pillar, as the Emergency Management Act does, also aligns with the current theory on emergency management. This subsection further explores each of these pillars in order to better understand EMAP's relevance in this particular context.

First Pillar: Mitigation (and Prevention)

The aim of mitigation is to reduce the severity of consequences of an emergency by identifying potential emergency situations and vulnerabilities. Unlike the other three pillars, which focus on finding short-term solutions, mitigation aims to establish long-term strategies that reduce risks.

Activities falling under the mitigation pillar are of a distinct nature. While response and recovery activities are largely operational, mitigation involves strategic activities such as planning, political insight, negotiations, and public relations. Because of that, mitigation typically requires the participation of stakeholders who are outside the traditional emergency management circle.

Mitigation activities can be classified into structural and non-structural activities.[Note 6] Structural mitigation includes strengthening buildings and infrastructure to increase resistance to damage that would be caused by disasters. In the context of First Nations communities, raising homes in flood-prone areas would be a typical example of structural mitigation. Non-structural mitigation does not involve infrastructure. Rather, it requires planning within the context of the environment. Building new houses away from a known hazard or maintaining protective features of the natural environment are examples of non-structural mitigation.

Public Safety Canada has developed a list of activities that may be undertaken in the context of mitigation. It includes hazard mapping, adoption and enforcement of land use and zoning practices, implementing and enforcing building codes, flood plain mapping, burying of electrical cables to prevent ice build-up, raising of homes in flood-prone areas, and disaster mitigation public awareness programs.[Note 7]The Piikani Nation in Alberta offers a good illustration of what mitigation can achieve. Following a major flood event in 1995, the band council passed a resolution prohibiting residential development on flood plains and conducted environmental assessments to secure funding for the installation of larger culverts. It also invested resources to support infrastructure improvements to its wells. These efforts did reduce the severity of subsequent floods.

Not surprisingly, by reducing the magnitude of future disasters and the risks to life and property associated with them, the cost of disaster response and recovery can also be reduced.[Note 8]

Second pillar: preparedness

Preparedness is about effectively anticipating emergencies. Its goal is to predict potential hazards and develop possible solutions. This is done with the aim of saving lives and reducing damages and injuries. Preparedness may be referred to as "anticipatory measures taken to increase response and recovery capabilities,"[Note 9] or more simply, activities to improve the ability of people and systems to manage an emergency when it occurs. As preparedness assumes that a disaster is likely to occur, it differs from the assumption of mitigation that a disaster may be prevented or that its effects may be minimized.

The main activity undertaken in the context of preparedness is the development of emergency management plans. As stated in subsection 3.1.1, the development of emergency plans is a specific requirement of the Emergency Management Act. Meaningful emergency plans require ongoing monitoring, updates, along with the appropriate training, exercising and public education.

By their very nature, preparedness activities require the involvement of all key sectors of the targeted community. Political authority, program managers, community organizations, first responders, as well as individuals and families, must participate in adequately preparing their community to deal with emergencies.

Third Pillar: Response

Response activities aim to effectively manage the immediate impact of an emergency on the community itself or its infrastructure. Typically, communities begin a response to an emergency using available resources, but when the required response exceeds the community's ability, a state of emergency is declared. This triggers the involvement of other organizations such as the provincial or territorial emergency management organizations.

As scenarios of emergencies vary significantly, so do the types of response activities that may be required. One of the first activities typically undertaken is the establishment of an operations centre. Once this is in place, the list of other activities that may be undertaken includes:

- Temporary relocation of individuals and families. This includes the provision

of shelter, food, clothing, and required social and community services

- Provision of medical care

- Provision of essential services and equipment to sustain public infrastructure

- Security measures

- Provision of telecommunications equipment

- Provision of counselling services to those affected by the disaster or its response[Note 10]

Response activities are normally undertaken by first responders, such as emergency management staff, firefighters, police officers, or paramedics. The Canadian Red Cross may also be contracted to coordinate emergency responses and provide some of the required services. In the specific case of First Nations communities, two Aboriginal organizations in Canada are directly involved in emergency management, with a particular focus on preparedness and response:

- In Manitoba, the Manitoba Association of Native Fire Fighters provides

response services, particularly related to community evacuation. INAC provides

financial support to the organization to undertake emergency management activities

on INAC's behalf.

- In British Columbia, the First Nations' Emergency Services Society also offers a range of emergency management services, including response services. Again, INAC provides financial support to this organization.

Fourth Pillar: Recovery

The primary purpose of recovery is "to restore post-disaster condition to an acceptable level."[Note 11] Once the recovery phase is completed, the community should have gained back a certain level of stability. This pillar is closely linked to the response one. In executing recovery activities, a community may also wish to pursue mitigation goals by implementing long-term solutions to address certain vulnerabilities.

The list of activities that may be undertaken during the recovery stage includes:

- Returning individuals and families to the community

- Trauma counselling

- Repairs to essential community infrastructure and equipment, such as water

and sewage

- Clearance of various types of debris

- Costs associated with the rental of the required machinery to conduct

recovery activities

- Essential landscaping (following a flood, for instance)

- Property cleanup (elimination of mould in houses affected by a water-related emergency)[Note 12]

As with the response pillar, a variety of organizations may be involved during the recovery stage, from first responders and contractors to local, provincial, and federal authorities.

EMAP in Relation to the Four Pillars

At a fundamental level, EMAP is well-aligned with the four pillars of emergency management. The program's Terms and Conditions specifically refer to each of these four pillars, and describe the process program recipients are expected to follow to obtain financial assistance, along with funding criteria. There are, nonetheless, serious gaps in INAC's approach to implementing this mandate, and these are further explored in Section 4 of this report.

3.1.3 The role of other federal departments

It should be noted that INAC is not the only federal department having a direct stake in emergency management on First Nations reserves. For instance, Health Canada is leading a process to adopt new regulations on water and wastewater management on reserves, while Environment Canada is proposing new regulations on fuel tank storage. Both federal departments will be requiring emergency response plans as part of the roll-out of these regulations. This would create an opportunity for efficiencies to be realized if these departments were to approach First Nations together and develop an all-hazards emergency management plan, instead of having each department approaching communities separately.

3.2 EMAP in Relation to Other Emergency Management Programs

The relevance of EMAP is also determined by the extent to which it complements other programs dealing with emergency management. To this end, three areas are particularly relevant, and they are examined in this subsection.

3.2.1 The Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements Program